CHAPTER XII

TEMPLES AND TOMBS

Anyone travelling

through our own land, or through any European country, to see the great

buildings of long ago, would find that they were nearly all either

churches or castles. There are the great cathedrals, very beautiful and

wonderful; and there are the great buildings, sometimes partly palaces

and partly fortresses, where Kings and nobles lived in bygone days.

Well, if you were travelling in Egypt to see its great buildings, you

would find a difference. There are plenty of churches, or temples,

rather, and very wonderful they are; but there are no castles or

palaces left, or, at least, there are next to none. Instead of palaces

and castles, you would find tombs. Egypt, in fact, is a land of great

temples and great tombs.

Now, one can see

why the Egyptians built great temples; for they were a very religious

nation, and paid great honour to their gods. But why did they give so

much attention to their tombs? The reason is, as you will hear more

fully in another chapter, that there never was a nation which believed

so firmly as did the Egyptians that the life after death was far more

important than life in this world. They built their houses, and even

their palaces, very lightly, partly of wood and partly of clay, because

they knew that they were only to live in them for a few years. But they

called their tombs "eternal dwelling-places"; and they have made them

so wonderfully that they have lasted long after all the other buildings

of the land, except the temples, have passed away.

Plate 14.

Gateway of the Temple of Edfu.

First of

all, let me try to give you an idea of what an Egyptian temple must

have been like in the days of its splendour. People come from all parts

of the world to see even the ruins of these buildings, and they are

altogether the most astonishing buildings in the world; but they are

now only the skeletons of what the temples once were, and scarcely give

you any more idea of their former glory and beauty than a human

skeleton does of the beauty of a living man or woman. Suppose, then,

that we are coming up to the gates of a great Egyptian temple in the

days when it was still the house of a god who was worshipped by

hundreds of thousands of people.

As we pass out of

the narrow streets of the city to which the temple belongs, we find

ourselves standing upon a broad paved way, which stretches before us

for hundreds of yards. On either side, this way is bordered by a row of

statues, and these statues are in the form of what we call sphinxes —

that is to say, they have bodies shaped like crouching lions, and on

the lion-body there is set the head of a different creature. Some of

the sphinxes, like the Great Sphinx, have human heads; but those which

border the temple avenues have oftener either ram or jackal heads.

As we pass along

the avenue, two high towers rise before us, and between them is a great

gateway. In front of the gate-towers are two tall obelisks, slender,

tapering shafts of red granite, like Cleopatra's Needle on the Thames

Embankment. They are hewn out of single blocks of stone, carved all

over with hieroglyphic figures, polished till they shine like mirrors,

and their pointed tops are gilded so that they flash brilliantly in the

sunlight. Beside the obelisks, which may be from 70 to 100 feet high,

there are huge statues, perhaps two, perhaps four, of the King who

built the temple. These statues represent the King as sitting upon his

throne, with the double crown of Egypt, red and white, upon his head.

They also are hewn out of single blocks of stone, and when you look at

the huge figures you wonder how human hands could ever get such stones

out of the quarry, sculpture them, and set them up. Before one of the

temples of Thebes still lie the broken fragments of a statue of Ramses

II. When it was whole the statue must have been about 57 feet high, and

the great block of granite must have weighed about 1,000 tons — the

largest single stone that was ever handled by human beings. Plate 10

will give you some idea of what these huge statues looked like.

Fastened to the

towers are four tall flagstaves — two on either side of the gate — and

from them float gaily-coloured pennons. The walls of the towers are

covered with pictures of the wars of the King. Here you see him

charging in his chariot upon his fleeing enemies; here, again, he is

seizing a group of captives by the hair, and raising his mace or his

sword to kill them; but whatever he is doing, he is always gigantic,

while his foes are mere helpless human beings. All these carvings are

brilliantly painted, and the whole front of the building glows with

colour; it is really a kind of pictorial history of the King's reign.

Now we stand in

front of the gate. Its two leaves are made of cedar-wood brought from

Lebanon; but you cannot see the wood at all, for it is overlaid with

plates of silver chased with beautiful designs. Passing through the

gateway, we find ourselves in a broad open court. All round it runs a

kind of cloister, whose roof is supported upon tall pillars, their

capitals carved to represent the curving leaves of the palm-tree. In

the middle of the court there stands a tall pillar of stone, inscribed

with the story of the great deeds of Pharaoh, and his gifts to the god

of the temple. It is inlaid with turquoise, malachite, and

lapis-lazuli, and sparkles with precious stones.

At the farther side

of this court, another pair of towers and another gateway lead you into

the second court. Here we pass at once out of brilliant sunlight into

semi-darkness; for this court is entirely roofed over, and no light

enters it except from the doorway and from grated slits in the roof.

Look around you, and you will see the biggest single chamber that was

ever built by the hands of man. Down the centre run two lines of

gigantic pillars which hold up the roof, and form the nave of the hall;

and beyond these on either side are the aisles, whose roofs are

supported by a perfect forest of smaller columns.

Look up to the

twelve great pillars of the nave. They soar above your head, seventy

feet into the air, their capitals bending outwards in the shape of open

flowers. On each capital a hundred men could stand safely; and the

great stone roofing beams that stretch from pillar to pillar weigh a

hundred tons apiece. How were they ever brought to the place? And,

still more, how were they ever swung up to that dizzy height, and laid

in their places? Each of the great columns is sculptured with figures

and gaily painted, and the surrounding walls of the hall are all

decorated in the same way. But when you look at the pictures, you find

that it is no longer the wars of the King that are represented. The

inside of the temple is too holy for such things. Instead, you have

pictures of the gods, and of the King making all kinds of offerings to

them; and these pictures are repeated again and again, with endless

inscriptions, telling of the great gifts which Pharaoh has given to the

temple.

Finally we pass

into the Holy of Holies. Here no light of day ever enters at all. The

chamber, smaller and lower than either of the others, is in darkness

except for the dim light of the lamp carried by the attendant priest.

Here stands the shrine, a great block of granite, hewn into a

dwelling-place for the figure of the god. It is closed with cedar doors

covered with gold plates, and the doors are sealed; but if we could

persuade the priest to let us look within, we should see a small wooden

figure something like the one that we saw carried through the streets

of Thebes, dressed and painted, and surrounded by offerings of meat,

drink, and flowers. For this little figure all the glories that we have

passed through have been created: an army of priests attends upon it

day by day, dresses and paints it, spreads food before it, offers

sacrifices and sings hymns in its praise.

Behind the

sanctuary lie storehouses, which hold corn and fruits and wines enough

to supply a city in time of siege. The god is a great proprietor,

holding more land than any of the nobles of the country. He has a

revenue almost as great as that of Pharaoh himself. He has troops of

his own, an army which obeys no orders but his. On the Red Sea he has

one fleet, bringing to his temple the spices and incense of the

Southland; and from the Nile mouths another fleet sails to bring home

cedar-wood from Lebanon, and costly stuffs from Tyre. His priests have

far more power than the greatest barons of the land, and Pharaoh,

mighty as he is, would think twice before offending a band of men whose

hatred could shake him on his throne. Such was an Egyptian temple 3,000

years ago, when Egypt was the greatest power in the world.

But if the temples

of ancient Egypt are wonderful, the tombs are almost more wonderful

still. Very early in their history the Egyptians began to show their

sense of the importance of the life after death by raising huge

buildings to hold the bodies of their great men. Even the earliest

Kings, who lived before there was any history at all, had great

underground chambers scooped out and furnished with all sorts of things

for their use in the after-life. But it is when we come to that King

Khufu, who figures in the fairy-stories of Zazamankh and Dedi, that we

begin to understand what a wonderful thing an Egyptian tomb might be.

Not very far from

Cairo, the modern capital of Egypt, a line of strange, pointed

buildings rises against the sky on the edge of the desert. These are

the Pyramids, the tombs of the great Kings of Egypt in early days, and

if we want to know what Egyptian builders could do 4,000 years before

Christ, we must look at them. Take the largest of them, the Great

Pyramid, called the Pyramid of Cheops. Cheops is really Khufu, the King

who was so much put out by Dedi's prophecy about Rud-didet's three

babies. No such building was ever reared either before or since. It

stands, even now, 450 feet in height, and before the peak was

destroyed, it was about 30 feet higher. Each of its four sides measures

over 750 feet in length, and it covers more than twelve acres of

ground, the size of a pretty large field. But you will get the best

idea of how tremendous a building it is when I tell you that if you

used it as a quarry, you could build a town, big enough to hold all the

people of Aberdeen, out of the Great Pyramid; or if you broke up the

stones of which it is built, and laid them in a line a foot broad and a

foot deep, the line would reach a good deal more than halfway round the

world at the Equator. You would have some trouble in breaking up the

stones, however; for many of the great blocks weigh from 40 to 50 tons

apiece, and they are so beautifully fitted to one another that you

could not get the edge of a sheet of paper into the joints!

Inside this great

mountain of stone there are long passages leading to two small rooms in

the centre of the Pyramid; and in one of these rooms, called "the

King's Chamber," the body of the greatest builder the world has ever

seen was laid in its stone coffin. Then the passages were closed with

heavy plug-blocks of stone, so that no one should ever disturb the

sleep of King Khufu. But, in spite of all precautions, robbers mined

their way into the Pyramid ages ago, plundered the coffin, and

scattered to the winds the remains of the King, so that, as Byron says,

"Not a pinch of dust remains of Cheops."

The other pyramids

are smaller, though, if the Great Pyramid had not been built, the

Second and Third would have been counted world's wonders. Near the

Second Pyramid sits the Great Sphinx. It is a huge statue, human-headed

and lion-bodied, carved out of limestone rock. Who carved it, or whose

face it bears, we do not certainly know; but there the great figure

crouches, as it has crouched for countless ages, keeping watch and ward

over the empty tombs where the Pharaohs of Egypt once slept, its head

towering seventy feet into the air, its vast limbs and body stretching

for two hundred feet along the sand, the strangest and most wonderful

monument ever hewn by the hands of man (Plate 11).

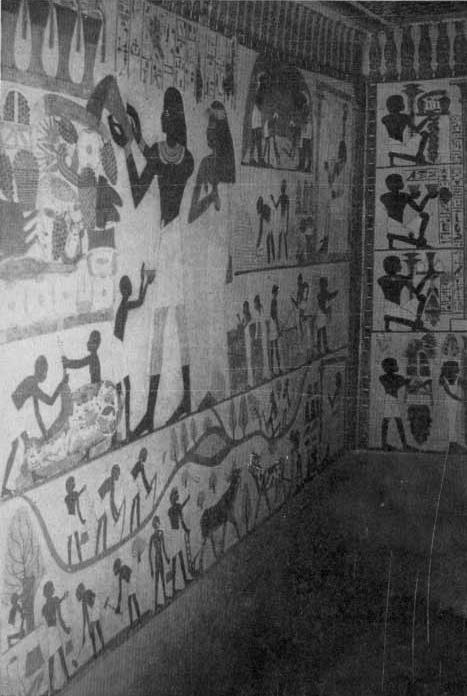

Later on in

Egyptian history the Kings and great folk grew tired of building

pyramids, and the fashion changed. Instead of raising huge structures

above ground, they began to hew out caverns in the rocks in which to

lay their dead. Round about Thebes, the rocks on the western side of

the Nile are honeycombed with these strange houses of the departed.

Their walls, in many cases, are decorated with bright and cheerful

pictures, showing scenes of the life which the dead man lived on earth.

There he stands, or sits, placid and happy, with his wife beside him,

while all around him his servants go about their usual work. They

plough and hoe, sow and reap; they gather the grapes from the vines and

put them into the winepress; or they bring the first-fruits of the

earth to present them before their master (Plate 15). In other pictures

you see the great man going out to his amusements, fishing, hunting, or

fowling; or you are taken into the town, and see the tradesmen working,

and the merchants, and townsfolk buying and selling in the bazaars. In

fact, the whole of life in Ancient Egypt passes before your eyes as you

go from chamber to chamber, and it is from these old tomb-pictures that

we have learned the most of what we know of how people lived and worked

in those long-past days.

In one wild rocky

glen, called the "Valley of the Kings," nearly all the later Pharaohs

were buried, and to-day their tombs are one of the sights of Thebes.

Let us look at the finest of them — the tomb of Sety I., the father of

that Ramses II. of whom we have heard so much. Entering the dark

doorway in the cliff, you descend through passage after passage and

hall after hall, until at last you reach the fourteenth chamber, "the

gold house of Osiris," 470 feet from the entrance, where the great King

was laid in his magnificent alabaster coffin. The walls and pillars of

each chamber are wonderfully carved and painted. The pillars show

pictures of the King making offerings to the gods, or being welcomed by

them, but the pictures on the walls are very strange and weird. They

represent the voyage of the sun through the realms of the under-world,

and all the dangers and difficulties which the soul of the dead man has

to encounter as he accompanies the sun-bark on its journey. Serpents,

bats, and crocodiles, spitting fire, or armed with spears, pursue the

wicked. The unfortunates who fall into their power are tortured in all

kinds of horrible ways; their hearts are torn out; their heads are cut

off; they are boiled in caldrons, or hung head downwards over lakes of

fire. Gradually the soul passes through all these dangers into the

brighter scenes of the Fields of the Blessed, where the justified sow

and reap and are happy. Finally, the King arrives, purified, at the end

of his long journey, and is welcomed by the gods into the Abode of the

Blessed, where he, too, dwells as a god in everlasting life.

The beautiful

alabaster coffin in which the mummy of King Sety was laid is now in the

Soane Museum, London. When it was discovered, nearly a century ago, it

was empty, and it was not till 1872 that some modern tomb-robbers found

the body of the King, along with other royal mummies, hidden away in a

deep pit among the cliffs. Now it lies in the museum at Cairo, and you

can see the face of this great King, its fine, proud features not so

very much changed, we can well believe, from what they were when he

reigned 3,200 years ago. In the same museum you can look upon the faces

of Tahutmes III., the greatest soldier of Egypt; of Ramses II., the

oppressor of the Israelites; and, perhaps most interesting of all, of

Merenptah, the Pharaoh who hardened his heart when Moses pled with him

to let the Hebrews go, and whose picked troops were drowned in the Red

Sea as they pursued their escaping slaves.

Plate 15.

Wall-pictures in a Theban Tomb.

It is very strange

to think that one can see the actual features and forms on which the

heroes of our Bible story looked in life. The reason of such a thing is

that the Egyptians believed that when a man died, his soul, which

passed to the life beyond, loved to return to its old home on earth,

and find again the body in which it once dwelt; and even, perhaps, that

the soul's existence in the other world depended in some way on the

preservation of the body. So they made the bodies of their dead friends

into what we call "mummies," steeping them for many days in pitch and

spices till they were embalmed, and then wrapping them round in fold

upon fold of fine linen. So they have endured all these hundreds of

years, to be stored at last in a museum, and gazed upon by people who

live in lands which were savage wildernesses when Egypt was a great and

mighty Empire.

|