CHAPTER IX

EXPLORING THE SOUDAN

There is no more

wonderful or interesting story than that which tells how bit by bit the

great dark continent of Africa has been explored, and made to yield up

its secrets. But did you ever think what a long story it is, and how

very early it begins? It is in Egypt that we find the first chapters of

the story; and they can still be read, written in the quaint old

picture writing which the Egyptians used, on the rock tombs of a place

in the south of Egypt, called Elephantine.

In early days the

land of Egypt used to end at what was called the First Cataract of the

Nile, a place where the river came down in a series of rapids among a

lot of rocky islets. The First Cataract has disappeared now, for

British engineers have made a great dam across the Nile just at this

point, and turned the whole country, for miles above the dam, into a

lake. But in those days the Egyptians used to believe that the Nile, to

which they owed so much, began at the First Cataract. Yet they knew of

the wild country of Nubia beyond and, in very early times indeed, about

5,000 years ago, they used to send exploring expeditions into that

half-desert land which we have come to know as the Soudan.

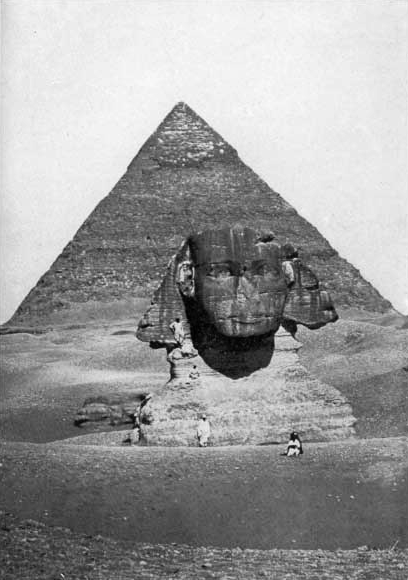

Plate 11.

The Sphinx and the Second Pyramid.

Near

the First Cataract there lies the island of Elephantine, and when the

Egyptian kingdom was young the great barons who

owned this island

were the Lords of the Egyptian Marches, just as the Percies and the

Douglases were the Lords of the Marches in England and Scotland. It was

their duty to keep in order the wild Nubian tribes south of the

Cataract, to see that they allowed the trading caravans to pass safely,

and sometimes to lead these caravans through the desert themselves. A

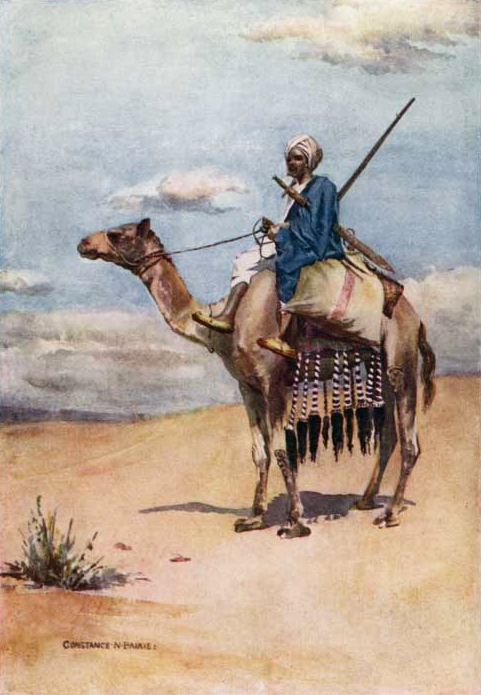

caravan was a very different thing then from the long train of camels

that we think of now when we hear the name. For, though there are some

very old pictures which show that, before Egyptian history begins at

all, the camel was known in Egypt, somehow that useful animal seems to

have disappeared from the land for many hundreds of years. The Pharaohs

and their adventurous barons never used the queer, ungainly creature

that carries the desert postman in our picture (Plate 12), and the

ivory, gold-dust, and ebony that came from the Soudan had to be carried

on the backs of hundreds of asses.

The barons of

Elephantine bore the proud title of "Keepers of the Door of the South,"

and, in addition, they display, seemingly just as proudly, the title

"Caravan Conductors." In those days it was no easy task to lead a

caravan through the Soudan, and bring it back safe with its precious

load through all the wild and savage tribes who inhabited the land of

Nubia. More than one of the barons of Elephantine set out with a

caravan never to return, but to leave his bones, and those of his

companions, to whiten among the desert sands; and one of them has told

us how, hearing that his father had been killed on one of these

adventurous journeys, he mustered his retainers, marched south with a

train of a hundred asses, punished the tribe which had been guilty of

the deed, and brought his father's body home, to be buried with all due

honours.

Some of the records

of these early journeys, the first attempts to explore the interior of

Africa, may still be read, carved on the walls of the tombs where the

brave explorers sleep. One baron, called Herkhuf, has told us of no

fewer than four separate expeditions which he made into the Soudan. On

his first journey, as he was still young, he went in company with his

father, and was away for seven months. The next time he was allowed to

go alone, and brought back his caravan safely after an absence of eight

months.

On his third

journey he went farther than before, and gathered so large a quantity

of ivory and gold-dust that three hundred asses were required to bring

his treasure home. So rich a caravan was a tempting prize for the wild

tribes on the way; but Herkhuf persuaded one of the Soudanese chiefs to

furnish him with a large escort, and the caravan was so strongly

guarded that the other tribes did not venture to attack it, but were

glad to help its leader with guides and gifts of cattle. Herkhuf

brought his treasures safely back to Egypt, and the King was so pleased

with his success that he sent a special messenger with a boat full of

delicacies to refresh the weary traveller.

But the most

successful of all his expeditions was the fourth. The King who had sent

him on the other journeys had died, and was succeeded by a little boy

called Pepy, who was only about six years old when he came to the

throne, and who reigned for more than ninety years — the longest reign

in the world's history. In the second year of Pepy's reign, the bold

Herkhuf set out again for the Soudan, and this time, along with other

treasures, he brought back something that his boy-King valued far more

than gold or ivory.

You know how, when

Stanley went in search of Emin Pasha, he discovered in the Central

African forests a strange race of dwarfs, living by themselves, and

very shy of strangers. Well, for all these thousands of years, the

forefathers of these little dwarfs must have been living in the heart

of the Dark Continent. In early days they evidently lived not so far

away from Egypt as when Stanley found them, for, on at least one

occasion, one of Pharaoh's servants had been able to capture one of the

little men, and bring him down as a present to his master, greatly to

the delight of the King and Court. Herkhuf was equally fortunate. He

managed to secure a dwarf from one of these pigmy tribes, and brought

him back with his caravan, that he might please the young King with his

quaint antics and his curious dances.

When the King heard

of the present which his brave servant was bringing back for him, he

was wild with delight. The thought of this new toy was far more to the

little eight-year-old, King though he was, than all the rest of the

treasure which Herkhuf had gathered; and he caused a letter to be

written to the explorer, telling him of his delight, and giving him all

kinds of advice as to how careful he should be that the dwarf should

come to no harm on the way to Court.

Plate 12.

A Desert Postman.

The letter, through

all its curious old phrases, is very much the kind of letter that any

boy might send on hearing of some new toy that was coming to him. "My

Majesty," says the little eight-year-old Pharaoh, "wisheth to see this

pigmy more than all the tribute of Punt. And if thou comest to Court

having this pigmy with thee sound and whole, My Majesty will do for

thee more than King Assa did for the Chancellor Baurded." (This was the

man who had brought back the other dwarf in earlier days.) Little King

Pepy then gives careful directions that Herkhuf is to provide proper

people to see that the precious dwarf does not fall into the Nile on

his way down the river; and these guards are to watch behind the place

where he sleeps, and look into his bed ten times each night, that they

may be sure that nothing has gone wrong.

The poor little

dwarf must have had rather an uncomfortable time of it, one fancies, if

his sleep was to be broken so often. Perhaps there was more danger of

killing him with kindness and care, than if they had left him more to

himself; but Pepy's anxiety was very like a boy. However, Herkhuf

evidently succeeded in bringing his dwarf safe and sound to the King's

Court, and no doubt the quaint little savage proved a splendid toy for

the young King. One wonders what he thought of the great cities and the

magnificent Court of Egypt, and whether his heart did not weary

sometimes for the wild freedom of his lost home.

Herkhuf was so

proud of the King's letter that he caused it to be engraved, word for

word, on the walls of the tomb which he hewed out for himself at

Elephantine, and there to this day the words can be read which tell us

how old is the story of African exploration, and how a boy was always

just a boy, even though he lived five thousand years ago, and reigned

over a great kingdom.

|