| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2016 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

CHAPTER X

THE PEOPLE OF THE HILLS

In

delineating a strange race we are prone to disregard what is common in our own

experience and observe sharply what is odd. The oddities we sketch and remember

and tell about. But there is little danger of misrepresenting the physical

features and mental traits of the hill people, because among them there is one

definite type that greatly predominates. This is not to be wondered at when we

remember that fully three-fourths of our highlanders are practically of the

same descent, have lived the same kind of life for generations, and have

intermarried to a degree unknown in other parts of Our average mountaineer is

lean, inquisitive, shrewd. If that be what constitutes a Yankee, as is

popularly supposed outside of New England, then this Yankee of the South is as

true to type as the conventional Uncle Sam himself. A fat mountaineer is a

curiosity. The hill folk even seem to affect a slender type of comeliness. In Alice MacGowan’s Judith of the

Cumberlands, old Jepthah Turrentine says of one of his sons: “I named that

boy after the finest man that ever walked God’s green earth — and then the fool

had to go and git fat on me! Think of me with a fat son! I allers did

hold that a fat woman was bad enough, but a fat man ort p’intedly to be led out

and killed!” Spartan diet does not put

on flesh. Still, it should be noted that long legs, baggy clothing, and

scantiness or lack of underwear make people seem thinner than they really are.

Our highlanders are conspicuously a tall race. Out of seventy-six men that I

have listed just as they occurred to me, but four are below average American

height and only two are fat. About two-thirds of them are brawny or sinewy

fellows of great endurance. The others generally are slab-sided,

stoop-shouldered, but withey. The townsfolk and the valley farmers, being

better nourished and more observant of the prime laws of wholesome living, are

noticeably superior in appearance but not in stamina. Nearly all males of the

back country have a grave and deliberate bearing. They travel with the long,

sure-footed stride of the born woodsman, not graceful and lithe like a

moccasined Indian (their coarse brogans forbid it), but shambling

as if every joint had too much play. There is nothing about them to suggest the

Swiss or Tyrolean mountaineers; rather they resemble the gillies of the Scotch

Highlands. Generally they are lean-faced, sallow, level-browed, with rather

high cheek-bones. Gray eyes predominate, sometimes vacuous, but oftener hard,

searching, crafty — the feral eye of primitive man. From infancy these people

have been schooled to dissimulate and hide emotion, and ordinarily their faces

are as opaque as those of veteran poker players. Many wear habitually a sullen

scowl, hateful and suspicious, which in men of combative age, and often in the

old women, is sinister and vindictive. The smile of comfortable assurance, the

frank eye of good-fellowship, are rare indeed. Nearly all of the young people

and many of the adults plant themselves before a stranger and regard him with a

fixed stare, peculiarly annoying until one realizes that they have no thought

of impertinence. Many of the women are

pretty in youth; but hard toil in house and field, early marriage, frequent

child-bearing with shockingly poor attention, and ignorance or defiance of the

plainest necessities of hygiene, soon warp and age

them. At thirty or thirty-five a mountain woman is apt to have a worn and faded

look, with form prematurely bent — and what wonder? Always bending over the hoe

in the cornfield, or bending over the hearth as she cooks by an open fire, or

bending over her baby, or bending to pick up, for the thousandth time, the wet

duds that her lord flings on the floor as he enters from the woods — what

wonder that she soon grows short-waisted and round-shouldered? The voices of the highland

women, low toned by habit, often are singularly sweet, being pitched in a sad,

musical, minor key. With strangers, the women are wont to be shy, but

speculative rather than timid, as they glance betimes with “a slow, long look

of mild inquiry, or of general listlessness, or of unconscious and

unaccountable melancholy.” Many, however, scrutinize a visitor calmly for minutes

at a time or frankly measure him with the gipsy eye of Carmen. Outsiders, judging from the

fruits of labor in more favored lands, have charged the mountaineers with

indolence. It is the wrong word. Shiftless many of them are — afflicted with

that malady which As a class, they have great

and restless physical energy. Considering the quantity and quality of what they

eat there is no people who can beat them in endurance of strain and privation.

They are great walkers and carriers of burdens. Before there was a tub-mill in

our settlement one of my neighbors used to go, every other week, thirteen miles

to mill, carrying a two-bushel sack of corn (112 pounds) and returning with his

meal on the following day. This was done without any pack-strap but simply

shifting the load from one shoulder to the other, betimes. One of our women, known as

“Long Goody” (I measured her; six feet three inches she stood) walked eighteen

miles across the Smokies into Tennessee, crossing at an elevation of 5,000

feet, merely to shop more advantageously than she could at home. The next day

she shouldered fifty pounds of flour and some other groceries, and bore them

home before nightfall. Uncle Jimmy Crawford, in his seventy-second year came to

join a party of us on a bear hunt. He walked twelve miles across the mountain,

carrying his equipment and four days’ rations for himself and dogs.

Finding that we had gone on ahead of him he followed to our camp on Siler’s

Bald, twelve more miles, climbing another 3,000 feet, much of it by bad trail,

finished the twenty-four-mile trip in seven hours — and then wanted to turn in

and help cut the night-wood. Young mountaineers afoot easily outstrip a horse

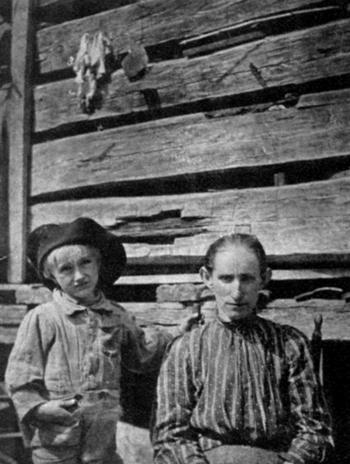

on a day’s journey by road and trail.  “At thirty a mountain woman is apt to have a worn and faded look”

In a climate where it

showers about two days out of three through spring and summer the women go

about, like the men, unshielded from the wet. If you expostulate, one will

laugh and reply: “I ain’t sugar, nor salt, nor nobody’s honey.” Slickers are

worn only on horseback — and two-thirds of our people had no horses. A man who

was so eccentric as to carry an umbrella is known to this day as “Umbrell’”

John Walker. In winter, one sometimes

may see adults and children going barefoot in snow that is ankle deep. It used

to be customary in our settlement to do the morning chores barefooted in the

snow. “Then,” said one, “our feet ’d tingle and burn, so ’t they wouldn’t git a

bit cold all day when we put our shoes on.” I knew a

family whose children had no shoes all one winter, and occasionally we had zero

weather. It seems to have been

common, in earlier times, to go barefooted all the year. Frederick Law Olmsted,

a noted writer of the Civil War period, was told by a squire of the Tennessee

hills that “a majority of the folks went barefoot all winter, though they had

snow much of the time four or five inches deep; and the man said he didn’t

think most of the men about here had more than one coat, and they never wore

one in winter except on holidays. ‘That was the healthiest way,’ he reckoned,

‘just to toughen yourself and not wear no coat.’ No matter how cold it was, he

‘didn’t wear no coat.’” One of my own neighbors in the Smokies never owned a

coat until after his marriage, when a friend of mine gave him one. It is the usual thing for

men and boys to wade cold trout streams all day, come in at sunset, disrobe to

shirt and trousers, and then sit in the piercing drafts of an open cabin drying

out before the fire, though the night be so cool that a stranger beside them

shivers in his dry flannels. After supper, the women, if they have been wearing

shoes, will remove them to ease their feet, no matter if it be freezing cold —

and the cracks in the floor may be an inch wide. In bear hunting, our

parties usually camped at about 5,000 feet above sea level. At this elevation,

in the long nights before Christmas, the cold often was bitter and the wind

might blow a gale. Sometimes the native hunters would lie out in the open all

night without a sign of a blanket or an axe. They would say: “La! many’s the

night I’ve been out when the frost was spewed up so high [measuring three or

four inches with the hand], and that right around the fire, too.” Cattle

hunters in the mountains never carry a blanket or a shelter-cloth, and they

sleep out wherever night finds them, often in pouring rain or flying snow. On

their arduous trips they find it burden enough to carry the salt for their

cattle, with a frying-pan, cup, corn pone, coffee, and “sow-belly,” all in a

grain sack strapped to the man’s back. Such nurture, from

childhood, makes white men as indifferent to the elements as Fuegians. And it

makes them anything but comfortable companions for one who has been differently

reared. During “court week” when the hotels at the county-seat are overcrowded

with countrymen, the luckless drummers who happen to be there have continuous

exercise in closing doors. No mountaineer closes a door behind him. Winter or summer, doors are to be shut only when

folks go to bed. That is what they are for. After close study of mountain

speech I have failed to discern that the word draft is understood, except in

parts of the Running barefooted in the

snow is exceptional nowadays; but it is by no means the limit of hardiness or

callosity that some of these people display. It is not so long ago that I

passed an open lean-to of chestnut bark far back in the wilderness, wherein a

family of Tennesseans was spending the year. There were three children, the

eldest a lad of twelve. The entire worldly possessions of this family could

easily be packed around on their backs. Poverty, however, does not account for

such manner of living. There is none so poor in the mountains that he need rear

his children in a bark shed. It is all a matter of taste. There is a wealthy man

known to everyone around Waynesville, who, being asked where he resided, as a

witness in court, answered: “Three, four miles up

and down This man is worth over a

hundred thousand dollars. He visited the world’s fairs at I cite these last two

instances not merely as eccentricities of character, but as really typical of

the bodily stamina that most of the mountaineers can display if they want to.

Their smiling endurance of cold and wet and privation would have endeared them

to the first Napoleon, who declared that those soldiers were the best who

bivouacked shelterless throughout the year. In spite of such apparent

“toughness,” the mountaineers are not a notably

healthy people. The man who exposes himself wantonly year after year must pay

the piper. Sooner or later he “adopts a rheumatiz,” and the adoption lasts till

he dies. So also in dietary matters. The backwoodsmen through ruthless

weeding-out of the normally sensitive have acquired a wonderful tolerance of

swimming grease, doughy bread and half-fried cabbage; but, even so, they are

gnawed by dyspepsia. This accounts in great measure for the “glunch o’ sour

disdain” that mars so many countenances. A neighbor said to me of another: “He

has a gredge agin all creation, and glories in human misery.” So would anyone

else who ate at the same table. Many a homicide in the mountains can be traced

directly to bad food and the raw whiskey taken to appease a soured stomach. Every stranger in Extremely early marriages

are tolerated, as among all primitive people. I knew a hobbledehoy of sixteen

who married a frail, tuberculous girl of twelve, and in the same small

settlement another lad of sixteen who wedded a girl of thirteen. In both cases

the result was wretched beyond description. The evil consequences of

inbreeding of persons closely akin are well known to the mountaineers; but here

knowledge is no deterrent, since whole districts are interrelated to start

with. Owing to the isolation of the clans, and their extremely limited travels,

there are abundant cases like those caustically mentioned in King Spruce:

“All Skeets and Bushees, and married back and forth and crossways and upside

down till ev’ry man is his own grandmother, if he only knew enough to figger

relationship.” The mountaineers are touchy

on these topics and it is but natural that they should be so. Nevertheless it

is the plain duty of society to study such conditions and apply the remedy.

There was a time when the Scotch people (to cite only one instance out of many)

were in still worse case, threatened with race

degeneration; but improved economic conditions, followed by education, made

them over into one of the most vigorous of modern peoples. When I lived up in the

Smokies there was no doctor within sixteen miles (and then, none who ever had

attended a medical school). It was inevitable that my first-aid kit and limited

knowledge of medicine should be requisitioned until I became a sort of “doctor

to the settlement.” 8 My services, being free, at once became

popular, and there was no escape; for, if I treated the Smiths, let us say, and

ignored a call from the Robinsons, the slight would be resented by all Robinson

connections throughout the land. So my normal occupations often were

interrupted by such calls as these: “John’s Lize Ann she ain’t

much; cain’t you-uns give her some easin’-powder for that hurtin’ in her

chist?” “Old Uncle Bobby Tuttle’s

got a pone come up on his side; looks like he mought drap off, him bein’ weak

and right narvish and sick with a head-swimmin’.” “Ike Morgan Pringle’s

a-been horse-throwed down the clift, and he’s in a manner stone dead.” “Right sensibly atween the

shoulders I’ve got a pain; somethin’ ’s gone wrong with my stummick; I don’t

’pear to have no stren’th left; and sometimes I’m nigh sifflicated. Whut you

reckon ails me?” “Come right over to Mis’ Fullwiler’s,

quick; she’s fell down and busted a rib inside o’ her!” On these errands of mercy I

soon picked up some rules of practice that are not laid down in the books. I

learned to carry not only my own bandages but my own towels and utensils for

washing and sterilizing. I kept my mouth shut about germ theories of disease,

having no troops to enforce orders and finding that mere advice incited

downright perversity. I administered potent drugs in person and left nothing to

be taken according to direction except placebos. Once, in forgetfulness, I

left a tablet of corrosive sublimate on the mantel after dressing a wound, and

the man of the house told me next day that he had “’lowed to swaller it’ and

see if it wouldn’t ease his headache!” A geologist and I, exploring the hills

with a mountaineer, fell into discussion of filth diseases and germs, not

realizing that we were overheard. Happening to pass

an ant-hill, Frank remarked to me that formic acid was supposed to be

antagonistic to the germ of laziness. Instantly we heard a growl from our

woodsman: “By God, I was expectin’ to hear the like o’ that!” Ordinarily wounds are

stanched with dusty cobwebs and bound up in any old rag. If infection ensues, An injured person gets

scant sympathy, if any. So far as outward demeanor goes, and public comment,

the witnesses are utterly callous. The same indifference is shown in the face

of impending death. People crowd around with no other motive, seemingly, than

morbid curiosity to see a person die. I asked our local preacher what the folks

would do if a man broke his thigh so that the bone protruded. He merely

elevated his eyebrows and replied: “We’d set around and sing until he died.” The mountaineers’ fortitude

under severe pain is heroic, though often needless. For all minor operations

and frequently for major ones they obstinately refuse to take an anesthetic, being perversely suspicious of everything that they do

not understand. Their own minor surgery and obstetric practice is barbarous. A

large proportion of the mountain doctors know less about human anatomy than a

butcher does about a pig’s. Sometimes this ignorance passes below ordinary

common sense. There is a “doctor” still practicing who, after a case of

confinement, sits beside the patient and presses hard upon the hips for half an

hour, explaining that it is to “push the bones back into place; don’t you know

they allers comes uncoupled in the socket?” This, I suppose, is the limit; but

there are very many practicing physicians in the back country who could not

name or locate the arteries of either foot or hand to save their lives. It was here I first heard

of “tooth-jumping.” Let one of my old neighbors tell it in his own way: “You take a cut nail (not

one o’ those round wire nails) and place its squar p’int agin the ridge of the

tooth, jest under the edge of the gum. Then jump the tooth out with a hammer. A

man who knows how can jump a tooth without it hurtin’ half as bad as pullin’.

But old Uncle Neddy Cyarter went to jump one of his own teeth out, one time,

and missed the nail and mashed his nose with the

hammer. He had the weak trembles.” “I have heard of

tooth-jumping,” said I, “and reported it to dentists back home, but they

laughed at me.” “Well, they needn’t laugh;

for it’s so. Some men git to be as experienced at it as tooth-dentists are at

pullin’. They cut around the gum, and then put the nail at jest sich an angle,

slantin’ downward for an upper tooth, or upwards for a lower one, and hit one

lick.” “Will the tooth come at the

first lick?” “Ginerally. If it didn’t,

you might as well stick your head in a swarm o’ bees and fergit who you are.” “Are back teeth extracted

in that way?” “Yes, sir; any kind of a

tooth. I’ve burnt my holler teeth out with a red-hot wire.” “Good God!” “Hit’s so. The wire’d

sizzle like fryin’.” “Kill the nerve?” “No; but it’d sear the mar

so it wouldn’t be so sensitive.” “Didn’t hurt, eh?” “Hurt like hell for a

moment. I held the wire one time for Jim Bob Jimwright, who couldn’t reach the

spot for hisself. I told him to hold his tongue back; but when I touched the holler he jumped and wropped his tongue agin the

wire. The words that man used ain’t fitty to tell.” Some of the ailments common

in the mountains were new to me. For instance, “dew pizen,” presumably the

poison of some weed, which, dissolved in dew, enters the blood through a

scratch or abrasion. As a woman described it, “Dew pizen comes like a risin’,

and laws-a-marcy how it does hurt! I stove a brier in my heel wunst, and then

had to hunt cows every morning in the dew. My leg swelled up black to clar

above the knee, and Dr. Stinchcomb lanced the place seven times. I lay on a

pallet on the floor for over a month. My leg like to killed me. I’ve seed

persons jest a lot o’ sores all over, as big as my hand, from dew pizen.” A more mysterious disease

is “milk-sick,” which prevails in certain restricted districts, chiefly where

the cattle graze in rich and deeply shaded coves. If not properly treated it is

fatal both to the cow and to any human being who drinks her fresh milk or eats

her butter. It is not transmitted by sour milk or by buttermilk. There is a

characteristic fetor of the breath. It is said that milk from an infected cow

will not foam and that silver is turned black by it. Mountaineers

are divided in opinion as to whether this disease is of vegetable or of mineral

origin; some think it is an efflorescence from gas that settles on plants. This

much is certain: that it disappears from “milk-sick coves” when they are

cleared of timber and the sunlight let in. The prevalent treatment is an

emetic, followed by large doses of apple brandy and honey; then oil to open the

bowels. Perhaps the extraordinary distaste for fresh milk and butter, or the

universal suspicion of these foods that mountaineers evince in so many

localities, may have sprung up from experience with “milk-sick” cows. I have

not found this malady mentioned in any treatise on medicine; yet it has been

known from our earliest frontier times. Abraham Lincoln’s mother died of it. That the hill folk remain a

rugged and hardy people in spite of unsanitary conditions so gross that I can

barely hint at them, is due chiefly to their love of pure air and pure water.

No mountain cabin needs a window to ventilate it: there are cracks and

cat-holes everywhere, and, as I have said, the doors are always open except at

night. “Tight houses,” sheathed or plastered, are universally despised, partly

from inherited shiftlessness, partly for less obvious reasons. One of Miss MacGowan’s

characters fairly insulted the neighborhood by building a modern house. “Why

lordy! Lookee hyer, Creed,” remonstrated Doss Provine over a question of

matching boards and battening joints, “ef you git yo’ pen so almighty tight as

that you won’t git no fresh air. Man’s bound to have ventilation. Course you

can leave the do’ open all the time like we-all do; but when you’re a-holdin’

co’t and sech-like maybe you’ll want to shet the do’ sometimes — and then

whar’ll ye git breath to breathe?... All these here glass winders is blame

foolishness to me. Ef ye need light, open the do’. Ef somebody comes

that ye don’t want in, you can shet it and put up a bar. But saw the walls full

o’ holes an’ set in glass winders, an’ any feller that’s got a mind to can pick

ye off with a rifle ball as easy as not whilst ye set by the fire of an

evenin’.” When mountain people move

to the lowlands and go to living in tight-framed houses, they soon deteriorate

like Indians. It is of no use to teach them to ventilate by lowering windows

from the top. That is some more “blame foolishness” — their adherence to old

ways is stubborn, sullen, and perverse to a degree that others cannot

comprehend. Then, too, in the lowlands, they simply cannot stand the water. As Emma Miles says: “No

other advantages will ever make up for the lack of good water. There is a

strong prejudice against pumps; if a well must be dug, it is usually left open

to the air, and the water is reached by means of a hooked pole which requires

some skillful manipulation to prevent losing the bucket. Cisterns are

considered filthy; water that has stood overnight is ‘dead water,’ hardly fit

to wash one’s face in. The mountaineer takes the same pride in his water supply

as the rich man in his wine cellar, and is in this respect a connoisseur. None

but the purest and coldest of freestone will satisfy him.” Once when I was staying in

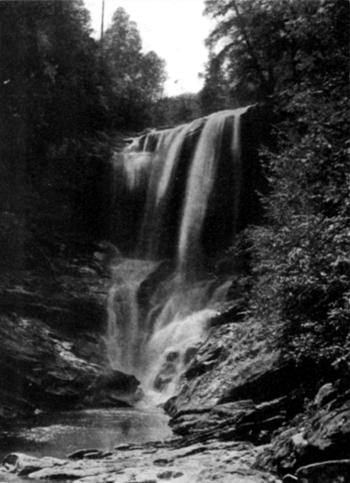

a lumber camp on the  Photo by Arthur Keith A misty veil of falling water A little colony of our Poor old John! In his

country there are a hundred spring branches running over poplar roots; but “that

thar poplar”: we knew the very one he meant. It was by the roadside. The

brooklet came from a disused still-house hidden in laurel and hemlock so dense

that direct sunlight never penetrated the glen. Cold and sparkling and crystal

clear, the gushing water enticed every wayfarer to bend and drink, whether he

was thirsty or no. John is back in his own land now, and doubtless often goes

to drink of that veritable fountain of youth. ______________ 8 In mountain dialect such

words as settlement, government, studyment (reverie) are accented on the last

syllable, or drawled with equal stress throughout. |