|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

V.

WATERFRONT AND HARBOR

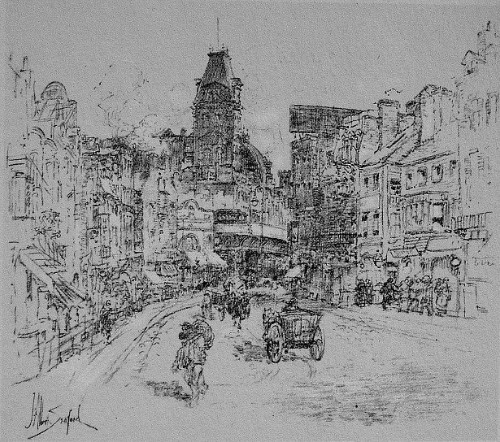

CAUSEWAY STREET; ANCIENT LOCATION OF THE MILL POND. BEYOND, THE NORTH

STATION.

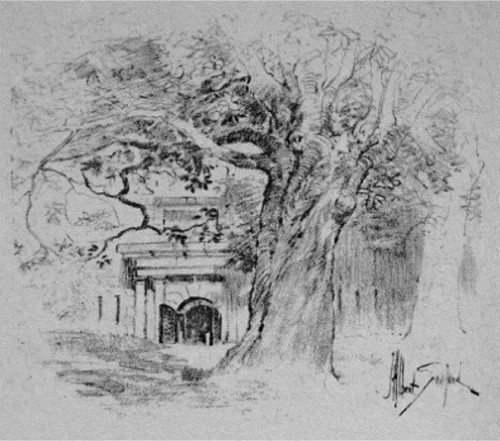

FORT INDEPENDENCE, FORMERLY THE CASTLE, ON CASTLE ISLAND, SOUTH BOSTON;

A REVOLUTIONARY DEFENCE. OCCUPIED BY THE BRITISH DURING THE SEIGE.

AFTER THE EVACUATION, GARRISONED BY AN ARTILLARY FORCE UNDER

PAUL REVERE.

IN his Wonder-working Providence in New England, Edward Johnson gives some idea of Boston in the first decade of its history. He mentions the two fortified eminences at the north and south, Copp's and Fort Hills, with the "Great Cove" between the beacon on the third hill, by which he doubtless means Beacon Hill, without reference to its three-pinnacled summit; the substantial character of the wharves, which the early Bostonians were shrewd enough to build in the interests of ocean commerce; and finally, "the buildings, large and beautiful, some fairly set forth with brick, tile, stone and slate, and orderly placed with seemly streets, whose continual enlargement presageth some sumptuous city."

We could forgive the slang, but how about the brick, tile, stone and slate? Other chroniclers fail to mention them, and even as late as 1803 the infrequency of brick buildings was noted by contemporary writers.

The southern fortification mentioned by Johnson was the so-called Southern Battery, on the seaward side of Fort Hill. This location corresponded to that of the present Rowe's wharf, where you take the boat to the beach. Fort Hill square is now as flat as your hand, but in the old days Fort Hill was a fair round knoll, crowned with a pleasant park and fine trees. In the eighteenth century the streets running up its sides were bordered with the homes of well-to-do citizens. In that section of town dwelt, also, many artisans employed in ropewalks and shipyards. That they were a husky crew is shown by the fact that only two days before the Boston Massacre occurred a riotous encounter between the "mechanics" and the British soldiers quartered thereabout, in which the townsmen scored a boisterous, if not very sanguinary victory.

At Griffin's wharf, nearby, the three teaships lay on December 16, 1773. Here came about a score of spurious Indians, followed by a willing crowd of excited men and boys, after an indignation meeting in the Old South Meeting House. In short order they boarded the vessels, siezed the three hundred and forty-two chests of tea, and emptied them upon the mud and ooze of the harbor-bottom, exposed by the ebb tide. Some of the invading party clambered down the piling and tramped the tea into the mud, as it poured over from the decks. The returning tide completed the work.

THE LOBSTER-BOAT FLEET, ATLANTIC AVENUE.

One of the party, Thomas Melvill, found tea in his shoes when he went home. This, sealed in a bottle, was kept as a memento of the affair, and is in the collection of the Bostonian Society today. No one was permitted knowingly to carry tea away, and if any tried to do so, he was promptly set upon. One such lost his coat-tails, in the pockets of which he had hidden a few handfuls of the herb. Next day the coat-tails were nailed upon the whipping post near their owner's house in Charlestown, with an appropriate placard.

Paul Revere, as you might readily suppose, was "among those present" at the Tea Party, and shortly afterwards set out on horseback for New York, with news of the occurrence, where it occasioned great enthusiasm. This was only one of his numerous official journeys in that direction. Seemingly, if a message needed carrying, someone always cried, "Where's Paul?"

Another name for the Southern Battery was the "Sconce," and from it Sconce lane led up to the fort on the hillside. This fort was begun in 1632, but the Sconce was the more strongly built and equipped. In fact, in 1743, when the Sconce mounted thirty-five guns, the fort seems to have disappeared. The British occupied this fortification with a garrison of four hundred men, and at the Evacuation left it in badly damaged condition, but the American forces repaired it.

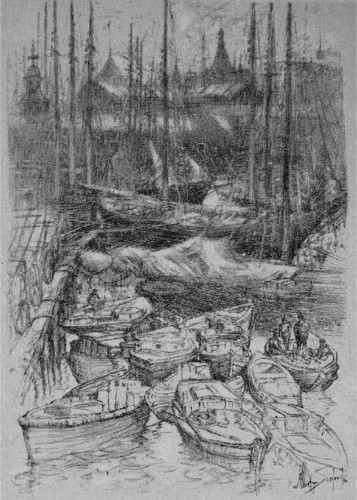

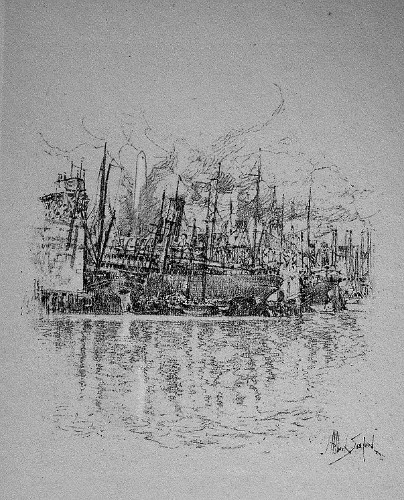

THE FISHING FLEET, AND THE WHOLESALE PRODUCE DISTRICT,

LOOKING PAST ATLANTIC AVENUE FROM THE WATERFRONT.

The harbor line extended irregularly from Fort Hill toward the present junction of Kilby and State streets, and it would be well to remember the hollow conformation of the shore in the early days. Sconce lane was afterwards called Hamilton street, and the way along the beach the "Batterymarch," a name that has come down to us, and which enables us to determine the former beach line with a degree of accuracy.

The indentation of the harbor known as Great Cove or Town Cove was divided about equally by Long wharf, a solid structure continuing the line of King (State) street. From its landward end near the present corner of Kilby street, it ran out two thousand feet. It was built in 1709-10, and supported rows of stores and warehouses. With the reclamation of the Cove, Long wharf sacrificed most of its length to State street.

The present shore line from Battery street to Rowe's wharf, as defined by Atlantic avenue, corresponds to the old Barricado, a stout defence of logs or piles which effectually enclosed the inner harbor. At the point where the Barricado cut Long wharf at right angles, and on the northern side of the latter, was Minott's T, a projection or offshoot of Long wharf, and joined to the Barricado as well. Its shape gave it the name, which has no reference to the Tea Party. By extension and alteration, T wharf became an independent jetty, having no connection with Long wharf.

When you detrain today at the South station, you issue upon a big, crowded plaza, named recently, as its title indicates, Dewey square. Turn and look back and up at the towering facade, surmounted by an enormous clock, usually set two comfortable minutes faster than standard time, a white and justifiable falsehood.

Twenty years ago there was no South terminal, but incoming travelers were set down at one or another of several scattered structures. Today all trains entering the city on the south side utilize the South station. Until within two or three years it was the largest railroad station on earth. Yet it is even now scarcely adequate for the traffic passing through it.

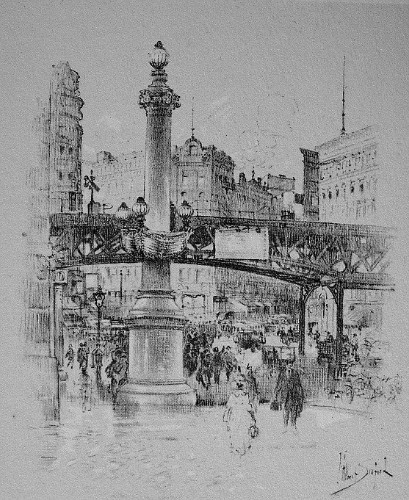

DEWEY SQUARE, FROM THE SOUTH STATION.

Our drawing of Dewey square was made from the main entrance of the terminal, and shows a teeming, sometimes congested, center of traffic. The elevated, of more recent erection than the station itself, sweeps past in a long curve, and apprehensive thousands "duck" timidly when the trains grind roaring and shrieking overhead. Several busy streets radiate from Dewey square. At morning and evening it is traversed by hurrying crowds, and a few souls forget the two minutes' grace of the big clock and run for trains with un-Bostonian abandon.

The location of the South station was formerly marsh and Atlantic avenue as far as Rowe's wharf was built upon low or marshy ground. It is paralleled by the Fort Point channel, which connects the harbor with the South bay, an inner basin now lined with wharves, coal-pockets and lumber docks.

Along the "old Barricado," now Atlantic avenue, from Rowe's wharf to Battery wharf, a great number of docks and quays jut out, with an irregular suggestion of comb teeth. Long and T wharves are of the number given over to the fishing industry. Massachusetts surely feeds the nation on Fridays, for the fisher-folk of Boston, Gloucester, Provincetown and lesser ports winnow the deep the year around. Sometimes, after a storm at sea, the vessels, big and little, that dock along Atlantic avenue come in with every spar and strand thickly coated with ice. But nothing daunts the "Captains Courageous" of the New England fishing fleets.

From the elevated train you will see the fruit company's "banana boats," in from Jamaica, discharging cargoes for trans-shipment to points inland. The bananas come to port green, but before you buy them for your own use they will have been ripened in dark, warm cellars. Finishing on the tree improves an orange, but bananas are better if captured in a green, undomesticated state. Occasionally the banana boat brings a stowaway, a big, fighting tarantula, with a hairy body as large as a half-dollar, and a dangerous bite.

It is said that the battle of Fort Hill, between the soldiers and the townsmen, was precipitated by the term "lobster," applied to a red-coat, by one of the mechanics. Since that day the lobster has become a creature of fashion, contributing largely to the high cost of livers, but his name finds no greater favor as an epithet than when used for the patriotic purpose of starting a pre-Revolutionary rumpus. The lobster fleet, consisting of many small craft, mostly power driven, should interest the gourmet who likes to know the origin of his delicacies; to the gourmand, we recommend the satisfying qualities of Boston baked beans and the New England boiled dinner.

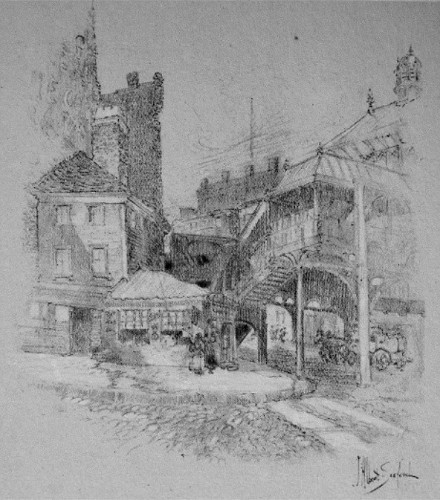

THE DOCKS AT CHARLESTOWN; BUNKER HILL MONUMENT.

Across the harbor, bulk the huge masses of elevator and dock in Charlestown and East Boston. Most of the tonnage lying at the wharves of Atlantic avenue is coast-wise. But, barring one German line, the passenger boats and freighters of the foreign-faring trade tie up at the farther shore. East Boston is on Noddle Island, a part of the city proper, where great manufactures thrive. From it we get electric lamps, ships, machinery and immigrants.

Back of the Charlestown docks rises Bunker Hill. The immediate vicinity of Bunker Hill is richer in historic association than in pictorial value, which explains why it is artistically wise to show the thin shaft of the Monument aspiring slenderly in the afternoon sun, its tall shape emphasized by contrast with the gray of the docks and ships.

Just beyond Battery street, at Copp's Hill, the settlers established the North Battery, which Edward Johnson described as "a very strong battery built of whole timber and filled with earth." It is first mentioned in the records of 1644. Battery wharf perpetuates its name. Major Pitcairn, of the First Battalion of Marines, was one of the British officers who embarked from the North Battery on the day of Bunker Hill, a day upon which he displayed a fatal gallantry. He, you will remember, was reported to have stirred his grog with his finger at Wright's Tavern, Concord, on April 19, stating as he did so, that the damned Yankees' blood would be similarly "stirred" before night. Viewing the bravery of his death, we may charitably overlook that boast.

Soon after the settlement of Boston, the colonists began to build ships. Oddly enough, the first of these was launched on July 4, in the year 1631, at Medford, a short distance up the Mystic river. The shipyards of Boston were established along the North End waterfront, and the shipwrights formed a group, powerful in politics, whose opinion was always seriously considered. Our term "caucus," applied to a political meeting, is said to have sprung from the gatherings of "calkers" in the famous old public houses of the North End.

BATTERY STREET STATION; NEAR THE SITE OF THE NORTH

BATTERY, AND OF HARTT'S SHIPYARD.

Of the hundreds of vessels built in the palmy days of marine construction in Boston, the most notable was the frigate Constitution, "Old Iron-sides," the pride of the American navy. Her keel was laid in Hartt's shipyard, the site of the present Constitution wharf. No modern dreadnaught ever aroused a fraction of the enthusiasm occasioned by her planning and building. On the day set for her launching, September 20, 1797, thousands of people crowded the neighboring shores and wharves; but when the signal was given, she failed to take the water. A second attempt, on the 22nd, proved unsuccessful; but on Saturday, October 21, she slid down the ways, observed by only a few people, since many had declared her "ill-fated," and perhaps thought she would never be floated. Her subsequent career in the service, and long life, not yet at an end, have shown the emptiness of that superstitious fear.

If the Constitution typified one aspect of the Boston spirit, let us consider a modern example of a different sort. On any summer day you may see, either at anchor in the roadstead, or nosing unobtrusively among the shipping, an odd-looking, many-windowed craft of the house-boat order, cargoed with sick babies and tired mothers. Her daily trips, made possible by the generosity of hundreds of men, women and children, sometimes expressed in pennies, often in an individual contribution sufficient for the expense of an entire day, register the throbbing of a great heart full of tenderness and pity for the helpless. This is the Boston Floating Hospital.

"Peace hath her victories, no less renowned than war."

Click the book image to continue to the next chapter