[Thanks to Fred Zweig for providing the scanned copies to add the images for the Article below.

See Mr. Zweig's blog on modern metalcrafting at:

http://fredz49.blogspot.com/ ]

[Science Illustrated, January, 1949, pages 82 - 87.]

Science Illustrated Visits

A Master Coppersmith

A little more than

a quarter century ago, he was a captain in the Czar's

Imperial Guard,

then a coal miner, and later a taxi driver -- before he learned to make

fine copperware.

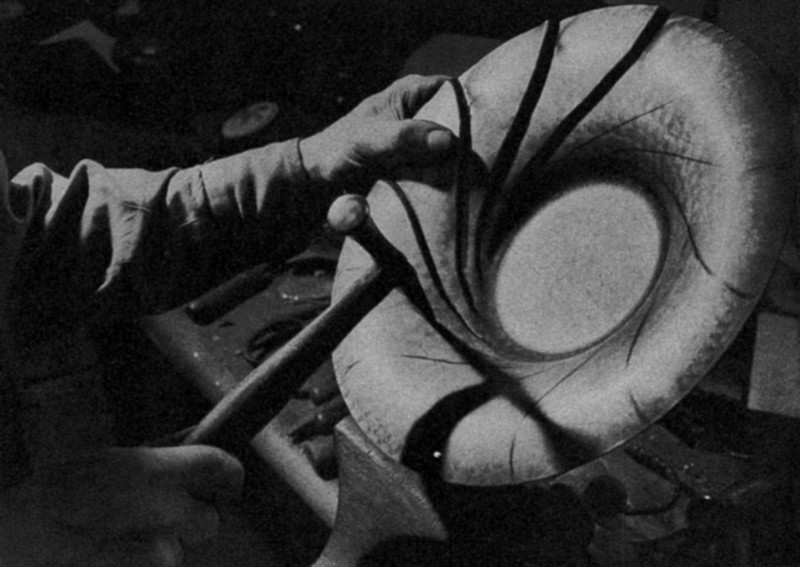

| Serge Nekrassoff examines a copper bowl that brought a group of metalsmiths to his shop for proof that it could be made by hand. Indentations made by a sharp-edged hammer form patterns in dark areas. Potassium sulphate is used to blacken metal. |

Serge Nekrassoff is a slender, gray-haired man in his middle fifties, with an easy-going manner and just a trace of an accent. His stamp on fine hand-made copperware has made his name a byword among decorators from coast to coast. Many of them call in person at his workshop -- a homey, rambling building in Darien, Conn. At a casual glance, you might take his place for a country restaurant or a private home, but for the sign "Serge Nekrassoff" above the door.

Inside, you will find almost every metal craft tool devised, from ancient iron anvils to modern spinning lathes. Nekrassoff knows how to make the most of all of them, as do the seven other master metalsmiths that make up his staff. But of all the tools, none are equal in performance to a simple set of hammers in his hands.

Some of Nekrassoff's work involves such complex shaping that other metal craftsmen refuse to believe it can be done by hand -- until they are shown. The tray shown in the photographs on these pages is an example. It brought a delegation of coppersmiths to Nekrassoff's shop. They told him that they would have to be convinced it wasn't stamped by machine. While they watched, Nekrassoff made a duplicate.

Ironically, Nekrassoff never intended to be a craftsman. But as things worked out he didn't have much choice in the matter. He had been an officer in the guard of the Czar until the Russian revolution forced him to flee to France. There, he tried working in a coal mine until his fellow refugees persuaded him that he could make a better living driving a taxicab in Paris.

But the discomfort of the French taxicabs finally forced him to become a craftsman. It had been a struggle getting a cab driver's license. Nekrassoff had to know the name of every street and alley in Paris. When he finally passed his test he had high hopes for his future as a cabbie. Then he was assigned to his cab -- and there his hopes ended. It was a relic, with an open drive and an outside hand brake. To make matters worse, it was mid-winter and Nekrassoff had no overcoat. After a week of zero weather, Nekrassoff signed up for three years as an apprentice in a metal-working shop -- where he could be close to the annealing ovens. (Annealing ovens provide high heat -- for copper -- to soften up metal.)

He began his coppersmithing career by doing very simple work -- hammering shallow trays. Soon he acquired what he calls the "feel" of the metal. He wanted to learn other processes -- spinning and casting -- but his employer said no. So for three years Nekrassoff hammered out trays.

To break the monotony of his work, he tried new techniques. By holding his hammer close to the side of his body, he learned to rain a steady rythmn of sharp machine-like hammer blows. To shape his trays, he moved the metal about beneath the hammer.

He learned, too, that the accuracy of his hammer strokes enabled him to finish much of his work with far less effort than was usually required. With no unnecessary working of the metal, he could produce complex shapes without the annealing that the average craftsman required to keep the copper soft and workable. And Nekrassoff's copperware never cracked. He knew the qualities of the metal so well that he could work it almost as a sculptor works his clay.

By the time his apprenticeship was completed, Nekrassoff felt sure of his ability. He was ready to go into business himself.

He put a major part of his three years' savings into a steam ship ticket to South America. The rest he put into the initial rent payment on a tiny shop in Buenos Aires, and into a small stock of metal. From this point on, Nekrassoff was more than thankful that those three years of monotonous tray-hammering led him to try new techniques. For Argentine taste in the 1920's called for ornamentation as elaborate as that in vogue in France. It kept Nekrassoff at his bench throughout the day, and often into the small hours of the morning -- producing pewter and copperware that was to fill his display shelves.

When he opened his door for business Nekrassoff was quickly rewarded for the effort he had spent transforming his stock of metal into intricate craftework. Customers all but filled his little shop. They bought his work and kept him rather busy.

He might have expanded his enterprise right there in Buenos Aires. But Nekrassoff had set a goal for himself of living and working in the United States. Each business day brought it a little nearer. When he finally sailed for New York he was able to make the trip without scraping, for his South American business had brought him more than enough to finance both the trip and a new ship. But this time starting his shop was a much more difficult task, for Nekrassoff had to turn out an almost complete set of metalware twice. The elaborate wares that sold so well in France and South America didn't sell in New York. Simplicity was the order of the day in American design.

There was just one thing to do -- put out an entire new line -- and Nekrassoff did. Once more the lights burned late over his workbench, and the machine-like beat of his hammers fashioned all new designs for a second start. Seventeen years have passed since then, but Nekrassoff still remembers the troubles of those first few weeks. Perhaps that's one of the reasons behind his favorite tip to fellow craftsmen -- "Remember your mistakes, and don't repeat them." Today, his shop runs at capacity to fill orders from all parts of the country, and Nekrassoff is busier than ever developing new designs and methods of turning them out.

His son, Boris, a U.S. paratroop veteran, handles the business end of the shop and Mrs. Serge Nekrassoff keeps tabs on both of them. "Otherwise," she says, "they'd forget to eat -- they like their work that much."

Photo Captions:

Ball-like bases of copperware are made by soldering individual pieces to base of bowl, after spinning, hammering, buffing.

1 FIRST STEP in making the bowl consists of hammering sheet copper disk on leather sandbag.

Center outline is penciled.

2 HARDWOOD LOG provides solid base for next step, sharpening outline of center of tray.

Wrinkles are removed later.

3 UPPER RIM is straightened with bowl inverted on log surface.

Metal is planished on a saddle tool with steel hammer.

4. CIRCULAR TEMPLATE placed over half-finished bowl is used to mark uniformly spaced

ridges on outer flange that will later be hammered out. Soft pencil lines.

5. SPIRAL PATTERN is outlined with curved guide, measured so it will form even design all around.

"Tail" of the guide is narrower because of smaller inside diameter.

6. SPECIAL ANVIL held in vise serves as backing as tipped hammer forms first part of ridges.

Depth of pattern is slowly lessened as spiral tapers towards the center.

7. SHARP-EDGED HAMMER is used to indent base of deep ridges, prior to darkening with chemical for contrast with polished upper surface. Center is already polished.

8. FINAL BUFFING produces mirror finish on copper. Special clear laquer is applied to finished tray to preserve high polish. Tray took three hours to make.

|

If

you want to try coppersmithing,

here is specific advice from a master coppersmith You can buy

yourself an

adequate group of metal working tools for about $25, and begin

your first project on a pre-cut disk. A soft copper blank 10

inches in diameter, of 18 guage thickness, costs about $1.15. You can

shape it on a sandbag, as shown in the photos, or on a wooden form.

Most of the tools and materials are available from hobby supply dealers

or such suppliers as Universal Handicrafts Service, Inc., 1267 Avenue

of the Americas, New York, N. Y.

The Tools You Should Have

Pointers on the Work 1.

Don't be afraid of the metal. Put plenty of elbow grease into your

first few projects. If you are working on a sandbag, the first few

hammer blows may produce a crumpled effect in the metal that will seem

frightening, but keep at it. It doesn't take long to transform that

seemingly hopeless mass into a bowl. Avoid making tight creases in the

metal. they're difficult to remove, and may cause cracks.

2. Try different methods of working the metal -- not merely the conventional ones. Watch the different shapes produced during the work. Some of the intermediate forms may suggest a new design to you. If you like the particular effect, try to reproduce it in scrap copper, then plan to apply it in a finished project. When you complete your first project, do a thorough job. Your first work can be fine work. 3. Remember your mistakes, and remember the steps that led up to them. If you can't correct them, you can at least avoid repeating them. Don't be afraid of spoiling a project or two when you are a beginner, but be sure to learn the reasons of your failures. Plan you[r] first few projects so as to use metal in economical sizes. Then you won't have a "timid hammer," and your work will be better. 4. Use soft copper before you try other harder metals like brass or silver. When you feel it harden during the work, anneal it by heating it to a dull red and quenching it in water. Use care when you do it, and take precautions to protect yourself from splatter. As you become more more experienced, you'll be able to do much of you[r] work without annealing your metal at all. 5. Learn to guage the power in your hammer blows so that you can produce the result you want in the metal without distorting it. Practice hammering in a single spot so that you develop accuracy. Learn to do this in a regular rhythm, and you will be able to move your work under the hammer blows for accurate shaping. Use a heavy bench or the end of an upright log for a working surface. |