|

Click

Here to return to

Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

|

CHAPTER XXX

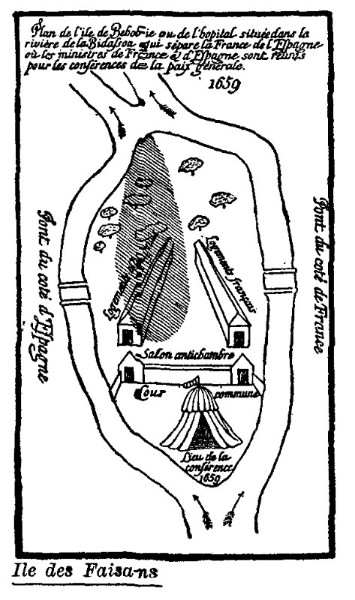

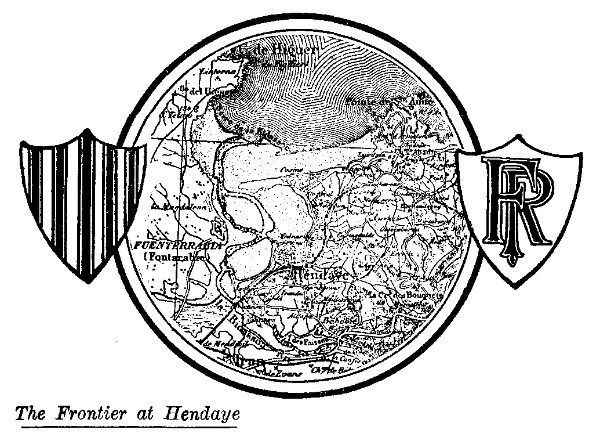

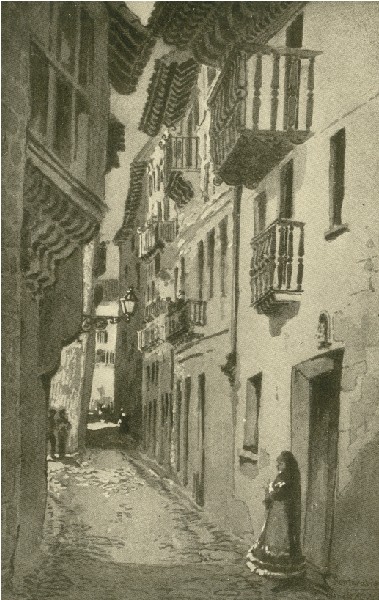

THE BIDASSOA AND THE FRONTIER IN the western valleys of the Pyrenees, opening out into the Landes bordering upon the Golfe de Gascogne, rises the little river Bidassoa, famous in history and romance. To the Basques its name is Bastanzubi, and its length is but sixty-five kilometres. In the upper valley, in Spanish territory, is Elizondo, the tiny capital of olden times, and three other tiny Spanish towns whose names suggest nothing but an old-world existence. In its last dozen or fifteen kilometres the Bidassoa forms the boundary between France and Spain, and mid-stream — below Hendaye, the last French station on the railway between Paris and Madrid — is the famous Ile des Faisans. All of this is classic ground. Just across the river from Hendaye is Irun, the first station on the Spanish railway line. It offers nothing special in the way of historical monuments, save a fourteenth-century Hôtel de Ville and innumerable old houses. Its characteristics are as much French as Spanish, and its speech the same, when its people don't talk Basque. A historic incident Of the Ile des Faisans was the famous affair of 1526, when, after the Battle of Pavia, and François Premier had been made prisoner by Charles V, the former was exchanged against his two children as hostages.  ILE DE FAISANS Three years later the children themselves were redeemed by another exchange, this time of much gold and many precious "relics," as one learns from the old chronicles. In 1615, on the same classic spot, as far from Spanish territory as from French, Anne of Austria, the fiancée of Louis XIII, was put into the hands of the French by the Spanish, who received in return Elizabeth Of France, fiancée of Philippe III. Quite a mart the Ile des Faisans had become! .The culminating event was the signing of the celebrated Traité des Pyrénées, on November 7th, 1659. When François Premier, fleeing from Madrid, where he had been the prisoner of Charles V, first set foot upon French soil again at this imaginary boundary line, he said: "At last I am a king again! Now I am really free." It was only through the efforts of his sister that François was able to escape his royal jailer. He had made promises which he did not intend to live up to; the king perjured himself but he saved France. He rode with all speed from Madrid to meet his boys, the Dauphin and the Duc d'Orleans, who were to replace him as hostages at Madrid. On the river's edge the sons were awaiting their father, with an emotion too vivid for description. They had no fear, and they entered willingly into the plan which was laid down for them, but the meeting and the parting was most sad. Wild with excitement of liberty being so near, François could hardly wait for the ferry to take him across, and even waded into the river to meet it as they pulled towards it. On French soil a splendid retinue awaited him, and once more the French king was surrounded by his luxurious court. To-day the Island of Pheasants is hardly more than a sand bar, and Mazarin and Don Louis de Haro, and their numerous suites would have a hard time finding a foothold. The currents of the river and the ocean have made of it only a pinhead on modern maps. In 1856, at the expense of the two countries, a stone memorial, with an inscription in French and Spanish, was erected to mark the site of this fast dwindling island. Irun and Feuntarrabia, with the three French communes of Biriaton, Béhobie and Hendaye enjoy reciprocal rights over the waters of the estuary of this epoch and history making river. This is the result of an agreement of long years standing, known as the "Pacte de Famille," an agreement made between the French and Spanish Basques (those of the béret bleu with the béret rouge) with the concurrence of the French and Spanish authorities. Crossing the Pont International between France and Spain may prove to be an amusing and memorable sensation. If a man at one end of the bridge offers you an umbrella, or a parasol, to keep off the sun's rays during this promenade, saying that you can leave it with a friend at the other end, don't take it. The other who would take it from you may be prevented from doing so by a Spanish gendarme or a customs official, who indeed is just as likely to catch you first. The fine is "easy" enough for this illicit traffic, but the international complications are many and great. So, too, will be the inconveniences to yourself. Around the Pont International, on both the French and Spanish sides, is as queer a collection of stray dogs and cats as one will see out of Constantinople. They are of a "race imprécise, vraies bêtes internationales," the customhouse officer tells you, and from their looks there's no denying it. They may not be wicked, may only bark and not bite, mew and not scratch, but only they themselves know this. To the rest of us they look suspicious. From Hendaye one may enter Spain by any one of three means of communication, — by railway, on foot across the Pont de Béhobie, or by a boat across the Bidassoa. The first means is the most frequented; for a piécette — that is to say a pièce blanche of Spanish money, which has the weight and appearance of a franc, but a considerably reduced value — one can cross by train; a boatman will take you for half the price at any time of the day or night; and by the Pont International, it costs nothing. This international bridge belongs half to France and half to Spain, the post in the middle bearing the respective arms marking the limits of the territorial rights of each.  THE FRONTIER AT HENDAYE This is one of the most curiously ordained frontiers in all the world. The people of Urrugne in France, twenty kilometres distant from the frontier, can hold speech freely in their mother tongue with those of Feuntarrabia in Spain, but officialdom of the customs and railway organizations at Hendaye and Trun, next-door neighbours, have to translate their speech from French to Spanish and vice versa, or have an interpreter who will. Curious anomaly this! Hendaye 's chief shrine is a modern one, the singularly-built house, on a rock dominating the bay, formerly inhabited by Pierre Loti, though most of his fellow townsmen knew him only as Julian Viaud, Lieutenant de Vaisseau. This, though the commander of the miserable little gunboat called the "Javelot" stationed always in the Bidassoa was an Académicien. At the French entrance to this important frontier bridge one reads on a Pauel PONT INTERNATIONAL; and at the Spanish end, PUENTE INTERNACIONAL; and here the gendarme of France become the carabiniero of Spain. Béhobie, at the Spanish end of the bridge, the French call "the biggest hamlet in Europe." It virtually is a hamlet, but it has some of the largest business and industrial enterprises in the country, for here have been established branch houses and factories of many a great French industry in order to avoid the tariff tax imposed on foreign products in the Spanish peninsula. The game has been played before elsewhere, but never so successfully as here. On the Pointe de Ste. Anne, the northern boundary of the estuary of the Bidassoa, is a monumental château, the work of Viollet-le-Duc, built by him for the Comte d'Abbadie. Modern though it is, its architectural opulence is in keeping with the knowledge of its builder (the greatest authority on Gothic the world has ever known, or ever will know); and as a combination of the excellencies of old-time building with modern improvements, this Château d'Abbadie stands quite in a class by itself. At the death of the widow of the Comte d'Abbadie, the château was bequeathed by her to the Institut de France.  MAISON PIERRE LOTI, HENDAYE The view seaward from the little peninsula upon which the château sits is marvellously soft and beautiful, and what matter it if the fish of the Golfe de Fontarabie to the south have no eyes — if indeed his statement be true. No oculist or zoologist has said it, but a poet has written thus: — "Le poisson qui rouvrit l'oeil mort du vieux Tobie Be joue au fond du golfe où dort foutarabie." Near by is the Forêt d'Yraty, much like most of the forests of France, except that this is all up and down hill, clinging perilously wherever there is enough loose soil for a tree to take root. The inhabitants tell you of a "wild man" discovered here by the shepherds, in 1774, long before the days of circus wild men. He was tall, well proportioned and covered with hair like a bear, and always in a good humour, though he did not speak an intelligible language. His chief amusement was sheep-stealing, and one day it was determined to take him prisoner. The shepherds and the authorities tried for twenty-five years, until finally he disappeared from view — and so the legend ends. Across the estuary of the Bidassoa, in truth, the Baie de Fontarabie, the sunsets are of a magnificence seldom seen. There may be others as gorgeous elsewhere, but none more so, and one can well imagine the same refulgent red glow, of which historians write, that graced the occasion when Cristobal Colon (or his Basque precursor) set out into the west. In connection with all this neighbouring Franco-Espagnol country of the Basques, one is bound to recall the great events of these last years, both at Biarritz, and at San Sebastian, across the border. The cachet of the king of England's approval has been given to the former, and of that of the king of Spain to the latter. Already the region has become known as the Côte d'Argent, as is the Riviera the Côte d'Azure, and the north Brittany coast the Côte d'Emeraud. It was here on the Côte d'Argent that King Alfonso did his wooing, his automobile flashing to and fro between St. Sebastian and Biarritz, crossing and recrossing the frontier stream of the Bidassoa. Bridges of stone and steel carry the traffic now, and it passes between Irun and Hendaye, higher up the river, but in the old days, the days of François I, the passage was more picturesquely made by ferry. Feuntarrabia is but a stone's throw away, sitting, as it were, desolate and forgotten on its promontory beyond the sands, and as the sun sets, flinging its blood-red radiance over sea and shore, the aspect is all very quiet, very peaceful, and fair. It is difficult to realize the stirring times that once passed over the spot, the war thunder that shook the echoes of the hills. May the bloody scenes of the Côte d'Argent be over for ever, and its future be as happy as King Alfonso's wooing. At Feuntarrabia, but a step beyond Irun, one enters his first typical Spanish town. You know this because touts try to sell you, and every one else, a lottery ticket, and because the beggars, who, apparently, are as numerous as their tribe in Naples, quote proverbs at your head. You

may understand them or you may not, but since Spain is the land of

proverbs, it is but natural that you should meet with them forthwith.

Here is one, though it is more like an enigma; and when translated it

becomes but an old friend in disguise — "Un

manco escribio una carts,

Un siega la esta miraudo; Un mudo la esta leyenda Y un sordo la esta escuchando." "A handless man a letter did write, A dumb dictated it word for word; The person who read it had lost his sight, And deaf was he who listened and heard." One need not be a phenomenal linguist to understand this, even in the vernacular. Feuntarrabia itself is a cluster of brown-red houses piled high along the narrow streets, with deep eaves over-hanging grated windows, and carved doorways leading to shady courts. There is a certain squalid, gone-to-ruin air about everything, which, in this case, is but a charm; but one can picture from the blazoned stone coats-of-arms seen here and there that the dwellers of olden time were proud and reverend seigneurs. Feuntarrabia, the little sea-coast town, called even by the French la perle de la Bidassoa is contrastingly different to Saint-Jean-de-Luz, though not twenty kilometres away. It is Spanish to the core, and on the escutcheon above the city gate one reads an ancient inscription to the effect that it belonged to the kings of Castile and was always "a very noble, very loyal, very brave and always faithful city."  IN OLD FEUNTARRABIA Feuntarrabia was once a fortress of renown, but that was in the long ago. It was a theatre of battles without end. Here Condé was repulsed, together with the best chivalry of France, and it was then that the grateful Spanish king ordered that for evermore it should be styled "the most noble, the most leal, the most valorous of cities" — a title which does actually appear on legal documents unto this day. The Duke of Berwick, King James Stuart's gallant son, once succeeded in taking the place, and it was then so utterly dismantled by the French that it bas never since been reckoned among the fortified places of Spain. But the city must indeed have felt the old war spirit stir again when it beheld those two great generals, Soult and Wellington, strive for victory before its hoary walls in 1813. Inch by inch the British had forced Napoleon's men from Spain; and here on the very frontier of France, Maréchal Soult gathered his forces for one last desperate stand. No British foot, he swore, should dare to touch the soil of France. But one chill October day, when the rain was falling on the broken, trodden vineyards, and the wind came moaning from the sullen sea, the word was given along the English ranks to pass the Bidassoa. And across the river came a line of scarlet fighting men, haggard and war-worn, many of them wounded, all of them weary. The result of that day is written on the annals of military glory as "one of the most daring exploits of military genius." Long afterwards Soult himself acknowledged it was the most splendid episode of the Peninsular War. THE END.

|

Web and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio

1999-2010

(Return to Web Text-ures)