| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

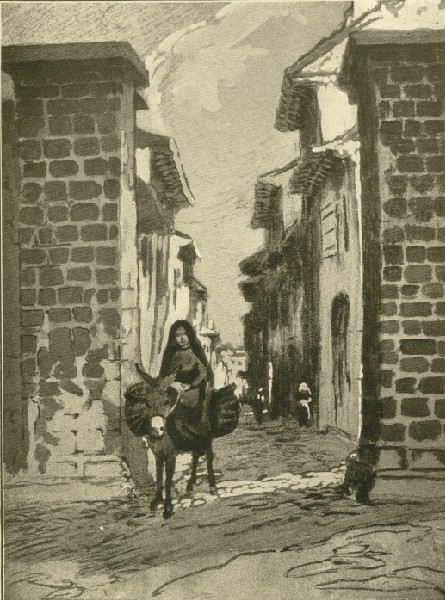

| CHAPTER XXVI

SAINT-JEAN-PIED-DE-PORT AND THE COL DERONÇEVAUX SAINT-JEAN-PIED-DE-PORT, the ancient capital of Basse-Navarre, is the gateway to one of the seven passes of the Pyrenees. To-day it is as quaint and unworldly as it was when capital of the province. Its aspect is truly venerable, and this in spite of the fact that it is the chief town of a canton, and transacts all the small business of the small officialdom of many square leagues of country within its walls. There is no apparent approach to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, as one comes up the lower valley of the Nive; it all opens out as suddenly as if a curtain were withdrawn; everything enlarges and takes on colouring and animation. The walled and bastioned little capital of other days was one of the clés of France in feudal times, and it lives well up to its traditions. Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port is a little town, red and rosy, as a Frenchman — certainly a poet, or an artist — described it. There is no doubt but that it is a wonder of picturesqueness, and its old walls and its great arched gateway tell a story of mediævalism which one does not have to go to a picture fairy book to have explained. All is rosy, the complexions of the young Basque girls, their costumes, the brick and stone houses and gates, and the old bridge across the Nive; all is the colour of polished copper, some things paler and some deeper in tone, but all rosy red. There's no doubt about that Along the river bank the houses plunge directly into the water without so much as a skirt of shore-line. Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, its ancient ramparts and its river, is a combination of Bruges and Venice. Its citadelle coiffe tells of things that are militant, and its fifteenth-century church of those that are spiritual. Between the two comes much history of the days when the little bourg was the weight in the balance between French and Spanish Navarre. The streets are calm, but brilliant with all the rare colourings of the artist's palette, not the least of these notes of colour being the milk jugs one sees everywhere hung out, strongly banded with great circles of burnished copper, and ornamented with a device of the royal crown, the fleur-de-lis, the initial H and the following inscription: "à le grand homme des pays béarnais et basques." No one seems to know the exact significance of this milk jug symbolism, but the jugs themselves would make good souvenirs to carry away. All around is a wonderful wooded growth, fig-trees, laurels and all the semi-tropical flora usually associated with the Mediterranean counties, including the châtaigniers, whose product, the chestnut, is becoming more and more appreciated as an article of food.  THE QUAINT STREETS OF SAINT-JEAN-PIED-DE-PORT Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port was, and is, the guardian of one of the most facile means of communication between France and Spain, the Route de Pamplona via Ronçevaux; facile because it has recently been rendered suitable for carriage traffic, whereas, save the coast routes on the east and west, no other is practicable. In 1523 the great tower and fortifications of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port were razed by order of the king of Navarre. The decree, dated and signed from "notre château de Pau," read in part thus: — "Know you that the demolition of the walls of the city of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port is not made for any case of crime or felony or suspicion against the inhabitants ... and that we consider said inhabitants still as good, faithful vassals and loyal subjects." The existing monuments of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port are many, though no royal residences are left to remind one of the days when kings and queens tarried within its walls. Instead one must be content with the knowledge that the city grew up from a Roman bourg which in the ninth century was replaced with the predecessor of the later capital. Its name, even in this early day, was Saint-Jean-le-Vieux, and it was not until the eleventh or twelfth centuries that the present city took form, founded doubtless by the Garcias, who were then kings of all Navarre. Saint-Jean belonged to Spain, as did all the province on the northern slope of the Pyrenees, until the treaty of 1659, and the capital of the kingdom was Pamplona. Under the three reigns preceding the French Revolution the city was the capital of French Navarre, but the French kings, some time before, as we have seen, deserted it for more sumptuous and roomy quarters at Pau, which became the capital of Béarn and Navarre. The chief architectural characteristics, an entrancing mélange of French and Spanish, are the remaining ramparts and their ogive-arched gates, the Vieux Pont and its fortified gateway, and the fifteenth and sixteenth century church. The local fête (August fifteenth-eighteenth) is typical of the life of the Basques of the region, and reminiscent, in its "charades," "bals champêtres," "parties de pelote," "mascarades," and "danses allegoriques" of the traditions of the past. Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port lies in the valley of the Nive, and St. Étienne-de-Baigorry, just over the crest of the mountains, fifteen kilometres away, in the Val de Baigorry, is the chief town of a commune more largely peopled than that presided over by Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port. Really the town is but a succession of hamlets or quarters, but it is interesting because of its church, with its great nave reserved exclusively for women, even to-day — as was the ancient Basque custom — and the Château d'Echaux sitting above the town. The château was the property of the ancient Vicomtes of Baigorry, and is a genuine mediæval structure, with massive flanking towers and a surrounding park. One of the Vicomtes de Baigorry, Bertrand d'Echaux, was also bishop of Bayonne, and afterwards almoner to Louis XIII. That monarch proposed to Pope Urban VIII to make his almoner a cardinal, but death overtook him first. The nephew of this Bertrand d'Echaux, Jean d'Olce, was also a bishop of Bayonne, and it was to him, in the church of St. Jean de Luz, fell the honour of giving the nuptial benediction to Louis XIV and the Infanta Marie-Thérèse upon their marriage. The Château de Baigorry of the Echaux belonged later to the Comte Harispe, one of the architects of the military glory of France. He first engaged in warfare as a simple volunteer, but died senateur, comte, and maréchal of France. There is a first class legend connected with the daughter of the chatelain of D'Echaux. A certain warrior, baron of the neighbouring château of Lasse, became enamoured of the daughter of the Seigneur d'Echaux, Vicomte de Baigorry, and in spite of the reputation of the suitor of being cruel and ungallant the vicomte would not willingly refuse the hand of his daughter to so valiant a warrior, so the young girl — though it was against her own wish — became la Baronne de Lasse. The marriage bell echoed true for a comparatively long period; it was said that the soft character of the lady had tempered the despotism of her husband. One day a young follower of Thibaut, Comte de Champagne, returning from Pamplona in Spain, knocked at the door of the Château de Lasse and demanded hospitality, as was his chevalier's right. The young knight and Madame la Baronne fell in love at first sight, but not without exciting the suspicions of the baron, who, by a subterfuge, caught the loving pair in their guilt. He threw himself upon the young gallant, pierced his heart with a dagger-thrust, cut him into pieces, and threw them into the moat outside the castle walls. An improvised court of justice was held in the great hall of the castle, and the vassals, fearing the wrath of their overlord, condemned the unhappy woman to death, by being interred in a dungeon cave and allowed to starve. When the Vicomte de Baigorry heard of this, he marched forthwith against his hard-hearted son-in-law, and after a long siege took the château. Just previously the baron committed suicide, anticipating the death that would have awaited him. This is tragedy as played in medieval times. Between Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port and Saint-Etienne-de-Baigorry, just by the side of the road, is the ruined château of Farges, a famous establishment in the days of the first Napoleon's empire, though a hot-bed of political intrigue. Its architectural charms are not many or great, the garden is neglected, and the gates are off their hinges. The whole resembles those Scotch manors now crumbling into ruin, of which Sir Walter has given so many descriptions. At Ascarat, too, is a house bearing a sculpture of a cross, a mitre, and two mallets interlaced on its façade, with the date 1292. It is locally called "La Maison Ancienne," but the present occupant has given it frequent coats of whitewash and repaired things here and there until it looks like quite a modern structure. Above Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, on the road to Arnéguy, is the little hamlet of Lasse, with a church edifice of no account, but with a ruined château donjon that possesses a historic, legendary past. It recalls the name of the baron who had that little affair with the daughter of the Vicomte de Baigorry. In the heart of the Pyrenees, twenty kilometres above Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, is Val Carlos and the Col de Ronçevaux, where fell Roland and Archbishop Turpin in that bloody rout of Charlemagne. Blood flowed in rivers. Literature more than history, though the event was epoch-making in the latter sense, has made the story famous. The French call it a drame militaire, and this, as well as anything, gives a suggestion of its spectacular features all so fully set forth in a cycle of chivalrous legends in the famous Song of Roland. The Alps divide their warlike glories with Napoleon and Hannibal, but the Pyrenees will ever have Charlemagne for their deity, because of this affair at Ronçevaux. Charlemagne dominated everything with his "host of Christendom," and the people on the Pyrenees say today: "There are three great noises — that of the torrent, that of the wind in the pines, and that of the army of Charlemagne." He did what all wise commanders should do; he held both sides of his defensive frontier. "When

Charlemagne had given his anger room,

And broken Saragossa beneath his doom, And bound the valley of Ebro under a bond, And into Christendom christened Bramimond." All who recall the celebrated retreat of Charlemagne and the shattering of his army, and the Paladin Roland, by the rocks rolled down upon them by the Basques will have vivid emotions as they stand here above the magnificent gorge of Val Carlos and contemplate one of the celebrated battle-fields of history. The abbey of Ronçevaux, a celebrated and monumental convent, has been famous long years in history. The royale et insigne collegiale, as it was known, was one of the most celebrated sanctuaries in Christendom, and takes its place immediately after the shrines of Jerusalem, Rome, and St. Jacques de Compostelle, under the immediate protection of the Holy See, and under the direct patronage of the king of Spain, who nominates the prior. This dignitary and six canons are all that exist today of the ancient military order of Ronçevaux, called by the Spanish Ronçevalles, and by the Basques Orhia. There's not much else at Ronçevaux save the monastery and its classic Gothic architectural splendours, a few squalid houses, and an inn where one may see as typical a Spanish kitchen as can be found in the depths of the Iberian peninsula. Here are all the picturesque Spanish accessories that one reads of in books and sees in pictures, soldiers playing guitars, and muleteers dancing the fandango, with, perhaps, a Carmencita or a Mercédès looking on or even dancing herself. Pamplona in Spain, the old kingly capital of Navarre, is eighty kilometres distant. One leaves Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port by diligence at eleven in the morning, takes déjeuner at Val Carlos, and at two in the afternoon takes the Spanish diligence and sleeps at Burgette, leaving again at four in the morning and arriving at Pamplona at eight. This is a classic excursion and ought to be made by all who visit the Pyrenees. Val Carlos is the Spanish customs station, and soon after one passes through the magnificent rocky Défile de Val Carlos and finally over the crest of the Pyrenees by either the Port d'Ibañeta or the Col de Ronçevaux, at a height of one thousand and fifty-seven metres. The route from Ronçevaux to Pamplona is equally as good on Spanish soil as it was on French — an agreeable surprise to those who have thought the good roads' movement had not "arrived" in Spain. The diligence may not be an ideally comfortable means of travel, but at least it's a romantic one, and has some advantages over driving from Saint Jean in your own, or a hired, conveyance, as an expostulating Frenchman we met had done. He freed the frontier all right enough, but within a few kilometres was arrested by a roving Spanish officer who turned him back to the official-looking building — which he had no right to pass without stopping anyway — labelled "Aduana Nacional" in staring letters, that any passer-by might read without straining his eyes. "Surely he would never have driven by in this manner," said the dutiful functionary, "unless he was intending to sell the horse and carriage and all that therein was, without acquitting the lawful rights which would enable a royal government to present a decent fiscal balance sheet." Pamplona is the end of our itinerary, and was the capital of Spanish Navarre. It's not at all a bad sort of a place, and while it doesn't look French in the least, it is no more primitive than many a French city or town of its pretentions. It has a population of thirty thousand, is the seat of a bishop, has a fine old cathedral, a bull ring — which is a sight to see on the fête day of San Sebastian (January twentieth) — and a hotel called La Perla which by its very name is a thing of quality. |