| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

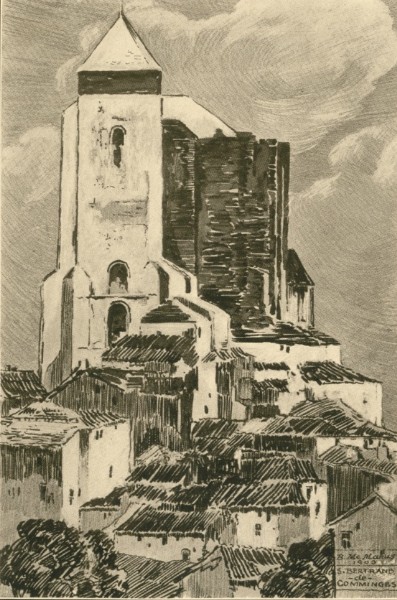

| CHAPTER XIV

THE PAYS DE COMMINGES ON the first steep slope of the Pyrenees, bounded on one side by Couserans and on the other by Bigorre, is the ancient Comté de Comminges, the territory of the Convènes, whose capital was Lugdunum Convenarum, established by Pompey from the remains left by the legions of Sertorius. Under the Roman emperors the capital became an opulent city, but to-day, known as St. Bertrand de Comminges, but seven hundred people think enough of it to call it home. It possesses a historic and picturesque site unequalled in the region, but Luchon, Montre-jean and St. Gaudens have grown at the expense of the smaller town, and its grand old cathedral church and ancient ramparts are little desecrated by alien strangers. The view of Comminges from a distance is uncommon and startling. One may see across a valley the outline of every rock and tree and housetop of the little town clustered about the knees of the swart, sturdy church of St. Bertrand of Comminges, one of the architectural glories of the mediæval builder. The mountains rise roundly all about and give a rough frame to an exquisite picture. What the precise date of the foundation of Comminges may be no one seems to know, though St. Jerome has said that it was a city built first by the montagnards in 79 B. C. This sacred chronicler called the founders "brigands," but authorities agree that he meant merely mountain dwellers. There is a profuse history of all this region still existing in the archives of the Département, which ranks among the most important of all those of feudal times still preserved in France. Only those of the Seine (Paris), Normandy (Rouen) and Provence (Marseilles and Aix) surpass it. In autumn St. Bertrand de Comminges is an enchanted spot, with all the colours of the rainbow showing in its ensemble. It is grandly superb, the panorama which unrolls from the terrace of the old chateau, succeeding ranges of the Pyrenees rising one behind the other, cloud or snow-capped in turn. St Bertrand, the ancient bishop's seat of Comminges, with the fortress walls surrounding the town and towering cathedral is, in a way, a suggestion of St. Michel's Mount off the Normandy coast, except there is no neighbouring sea. It is a townlet on a pinnacle. The constructive elements of the grim ramparts are Roman, but mediæval additions and copings have been interpolated from time to time so that they scarcely look their age. In the Ville Haute were built the cathedral and its dependencies, the château of the seigneurs, and the houses of the noblesse. Beyond these, but within another encircling wall, were the houses of the adherents of the counts; while outside of this wall lived the mere hangers-on. This was the usual feudal disposition of things. Eighty thousand people once made up the population of St. Bertrand. And three great highways, to Agen, to Dax, and to Toulouse, led therefrom. This was the epoch of its great prosperity. It is one of the most ancient Roman colonies in Aquitaine, and its history has been told by many chroniclers, one of the least profuse being St. Gregoire, Archbishop of Tours.  ST. BERTRAND DE COMMINGES After a frightful massacre in the ninth century the city, its churches, its château and its houses became deserted. It was a century later that Saint Bertrand de l'Isle, who had just been sanctified by his uncle the archbishop at Auch, undertook to reconstruct the old city on the ruins of its past. He re-established first the fallen bishopric, and elected himself bishop. This gave him power, and he started forthwith to build the singularly dignified and beautiful cathedral which one sees to-day. Comminges was made a comté in the tenth century, and the fief contained two hundred and eighty-eight towns and villages and nine castellanies, all owing allegiance to the Comte de Comminges. The episcopal jurisdiction varied somewhat from these limits, for it included twenty Spanish communes beyond the frontier as well. One enters St. Bertrand to-day by the great arched gateway, or Porte Majou, which bears over its lintel the arms of the Cardinal de Foix. As a grand historical monument St. Bertrand commences well. Narrow, crooked, little streets climb to the platform terrace above where sits the cathedral. It is a sad, grim journey, this mounting through the deserted streets, with here and there a Gothic or Renaissance column built helter-skelter into a house front, and the suggestion of a barred Gothic window or a delicate Renaissance doorway now far removed from its original functions. At last one reaches a great mass of tumbled stones which one is told is the ruin of the episcopal palace built by St. Bertrand himself. But what would you It is just this atmosphere of antiquity that one comes here to breathe, and certainly a more musty and less worldly one it would be difficult to find outside the catacombs of Rome. Another city gate, the Porte Cabirole, still keeps the flame of mediævalism alive; and, near by, is the most interesting architectural bit of all, a diminutive, detached tower-stairway, dating at least from the fifteenth century. It is an admirable architectural note, quite in contrast with all the grimness and sadness of the rest of the ruins. Opposite the entrance to the walled city is a curious monumental gateway, better described as a barbacane, or perhaps a great watch-tower, through which one has still to pass. The upper town had no source of water supply, so a well was cut down in the rock, and this tower served as its protection. There is another gate, still, in the encircling city walls, the third, the Porte de Herrison. After this, in making the round, one comes again to the Porte Majou, by which one entered. Rising high above all, on the top of the hill, as does the tower of the abbey on St. Michel's Mount, is the great, grim, newly coiffed tower of the cathedral of St. Bertrand, one of the most amply endowed and luxuriously installed minor cathedrals in all France. Its description in detail must be had from other works. It suffices here to state that the cathedral is of the town, and the town is of it to such an intermingled extent that it is almost impossible to separate the history of one from that of the other. The site of the cathedral is that of the old Roman citadel. Of the edifice built by St. Bertrand nothing remains but the first arches of the nave and the great westerly tower, really more like a donjon tower than a church steeple. In fact it is not a steeple at all. The whole aspect of St. Bertrand de Comminges, the city, the cathedral and the surroundings is militant, and looks as though it might stand off an army as well as undertake the saving of men's souls. The altar decorations, sculptured wood and carved stalls of the interior of this great church are very beautiful. Its like is not to be seen in France outside of Amiens, Albi and Rodez. The cloister, too, is superb. The happenings of the city since its reconstruction were not many, save as they referred to religion. Two bishops of the see became Popes, Clement V and Innocent VIII. The end of the sixteenth century brought the religious wars, and Huguenots and Calvinists took, and retook, the city in turn. With the Revolution came times nearly as terrible; and, in the new order of things following upon the Concordat, the bishopric was definitely suppressed. The few hundred inhabitants of to-day live in a city almost as dead as Pompeii or Les Baux. The word Comminges signifies an assembly inhabited by the Convenæ in the time of Cæsar. The inhabitants of feudal times were known as Commingeois. "The Commingeois are naturally warriors," wrote St. Bertrand de Comminges, and from this it is not difficult to follow the evolution of their dainty little feudal city, though difficult enough to find the reason for its practical desertion to-day. The Comtes de Comminges were an able and vigorous race, if we are to believe the records they left behind. There was one, Loup-Aznar, who lived in 932, who rode horse-back at the age of a hundred and five, and one of his descendants was married seven times. It was a Comte de Comminges, in the time of Louis XIV, who was compared by that monarch to a great cannon ball, whose chief efficiency was its size. Subsequently cannon balls, in France, came to be called "Comminges." Not a very great fame this, but still fame, and it was still for their warlike spirit that the Commingeois were commended. Jean Bertrand, a one-time Archbishop of Comminges, became a Cardinal of France upon the recommendation of Henri II. The king afterwards confessed that he was persuaded to urge his appointment by Diane de Poitiers, who was distributing her favours rather freely just at that time. The "Mémoires du Comte de Comminges" was the title borne by one of the most celebrated works of fiction of the eighteenth century — a predecessor of the Dumas style of romance. It is a work which has often been confounded by amateur students of French history with the "Mémoires du Philippe de Commines," who lived in another era altogether. The former was fiction, pure and simple, with its scene laid in the little Pyrenean community, while the latter was fact woven around the life of one who lived centuries later, in Flanders. |