| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

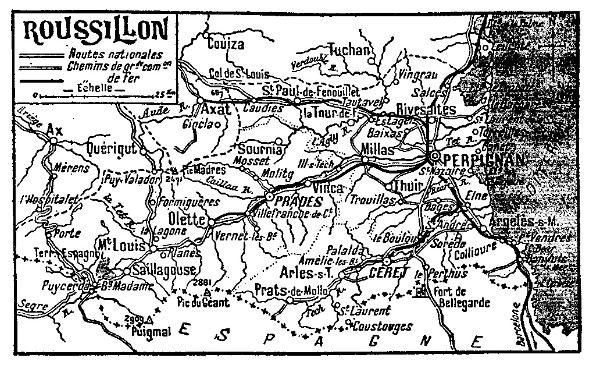

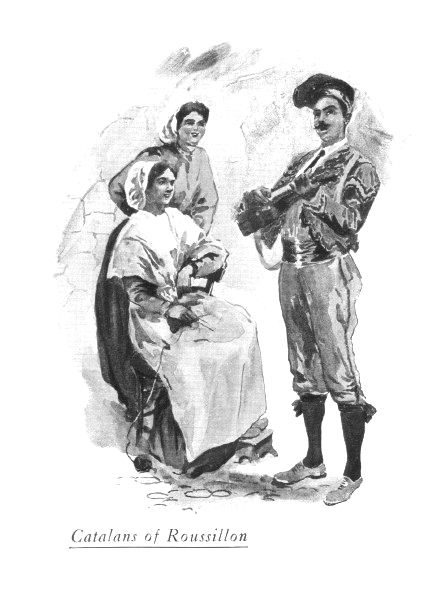

| CHAPTER V

ROUSSILLON AND THE CATALANS

ROUSSILLON is a curious province. "Roussillon is a bow with two strings," say the inhabitants. The workers in the vineyards of other days are becoming fishermen, and the fishermen are becoming vineyard workers. The arts of Neptune and the wiles of Bacchus have however conspired to give a prosperity to Roussillon which many more celebrated provinces lack. The Roussillon of other days, a feudal power in its time, with its counts and nobles, has become but a Département of latter-day France. The first historical epochs of Roussillon are but obscurely outlined, but they began when Hannibal freed the Pyrenees in 536, and in time the Romans became masters here, as elsewhere in Gaul. Then there came three hundred years of Visigoth rule, which brought the Saracens, and, in 760, Pepin claimed Roussillon for France. Then began the domination of the counts. First they were but delegates of the king, but in time they usurped royal authority and became rulers in their own right. Roussillon had its own particular counts, but in a way they bowed down to the king of Aragon, though indeed the kings of France up to Louis IX considered themselves suzerains. By the Treaty of Corbeil Louis IX renounced this fief in 1258 to his brother king of Aragon. At the death of James I of Aragon his states were divided among his children, and Roussillon came to the kings of Majorca. Wars within and without now caused an era of bloodshed. Jean II, attacked by the men of Navarre and of Catalonia, demanded aid of Louis XI, who sent seven hundred lances and men, and three hundred thousand gold crown pieces, which latter the men of Roussillon were obliged to repay when the war was over. Jean II, Comte de Roussillon, hedged and demanded delay, and in due course was obliged to pawn his count-ship as security. This the Roussillonnais resented and revolt followed, when Louis XI without more ado went up against Perpignan and besieged it on two occasions before he could collect the sum total of his bill. Charles VIII, returning from his Italian travels, in a generous frame of mind, gave back the province to the king of Aragon without demanding anything in return. Ferdinand of Aragon became in time king of Spain, by his marriage with Isabella, and Roussillon came again directly under Spanish domination. Meantime the geographical position of Roussillon was such that it must either become a part of France or a buffer-state, or duelling ground, where both races might fight out their quarrels. Neither François I nor Louis XIII thought of anything but to acquire the province for France, and so it became a battleground where a continuous campaign went on for years, until, in fact, the Grand Condé, after many engagements, finally entered Perpignan and brought about the famous Treaty of the Pyrenees, signed on the Ile des Faisans at the other extremity of the great frontier mountain chain. The antique monuments of Roussillon are not many; principally they are the Roman baths at Arles-sur-Tech, the tomb of Constant, son of Constantine, at Elne, and an old Mohammedan or Moorish mosque, afterwards serving as a Christian church, at Planes. The ancient city of Ruscino, the chief Roman settlement, has practically disappeared, a tower, called the Tor de Castel-Rossello, only remaining. Impetuosity of manner, freedom in their social relations, and a certain egotism have ever been the distinctive traits of the Roussillonnais. It was so in the olden times, and the traveller of to-day will have no difficulty in finding the same qualities. Pierre de Marca first discovered, and wrote of these traits in 1655, and his observations still hold good. Long contact with Spain and Catalonia has naturally left its impress on Roussillon, both with respect to men and manners. The Spanish tone is disappearing in the towns, but in the open country it is as marked as ever. There one finds bull-fights, cock-fights, and wild, abandoned dancing, not to say guitar twanging, and incessant cigarette rolling and smoking, and all sorts of moral contradictions — albeit there is no very immoral sentiment or motive. These things are observed alike of the Roussillonnais and the Catalonians, just over the border.  CATALANS OF ROUSSILLON The bull-fight is the chief joy and pride of the people. The labourer will leave his fields, the merchant his shop, and the craftsman his atelier to make one of an audience in the arena. Not in Spain itself, at Barcelona, Bilboa, Seville or Madrid is a bull-fight throng more critical or insistent than at Perpignan. He loves immensely well to dance, too, the Roussillonnais, and he often carries it to excess. It is his national amusement, as is that of the Italian the singing of serenades beneath your window. On all great gala occasions throughout Roussillon a place is set apart for dancing, usually on the bare or paved ground in the open air, not only in the country villages but in the towns and cities as well. The dances are most original. Ordinarily the men will dance by themselves, a species of muscular activity which they call "lo batl." A contrepas finally brings in a mixture of women, the whole forming a mélange of all the gyrations of a dervish, the swirls of the Spanish dancing girl and the quicksteps of a Virginia reel. The music of these dances is equally bizarre. A flute called lo flaviol, a tamborin, a hautboy, prima and tenor, and a cornemeuse, or Borrassa, usually compose the orchestra, and the music is more agreeable than might be supposed. In Roussillon the religious fêtes and ceremonies are conducted in much the flowery, ostentatious manner that they are in Spain, and not at all after the manner of the simple, devout fêtes and pardons of Bretagne. The Fête de Jeudi-Saint, and the Fête-Dieu in Roussillon are gorgeous indeed; sanctuaries become as theatres and tapers and incense and gay vestments and chants make the pageants as much pagan as they are Christian. The coiffure of the women of Roussillon is a handkerchief hanging as a veil on the back of the head, and fastened by the ends beneath the chin, with a knot of black ribbon at each temple. Their waist line is tightly drawn, and their bodice is usually laced down the front like those of the German or Tyrolean peasant maid. A short skirt, in ample and multifarious pleats, and coloured stockings finish off a costume as unlike anything else seen in France as it is like those of Catalonia in Spain.  THE WOMEN OF ROUSSILLON The great Spanish cloak, or capuchon, is also an indispensable article of dress for the men as well as for the women. The men wear a tall, red, liberty-cap sort of a bonnet, its top-knot hanging down to the shoulder — always to the left. A short vest and wide bodied Pantaloons, joined together with yards of red sash, wound many times tightly around the waist, complete the men's costume, all except their shoes, which are of a special variety known as spardilles, or espadrilles, another Spanish affectation. The speech of Roussillon used to be Catalan, and now of course it is French; but in the country the older generations are apt to know much Catalan-Spanish and little French. Just what variety of speech the Catalan tongue was has ever been a discussion with the word makers. It was not Spanish exactly as known to-day, and has been called roman vulgaire, rustique, and provincial, and many of its words and phrases are supposed to have come down from the barbarians or the Arabs. In 1371 the Catalan tongue already had a poetic art, a dictionary of rhymes, and a grammar, and many inscriptions on ancient monuments in these parts (eighth, ninth and tenth centuries) were in that tongue. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the Catalan tongue possessed a written civil and maritime law, thus showing it was no bastard. A fatality pursued everything Catalan however; its speech became Spanish, and its nationality was swallowed up in that of Castille. At any rate, as the saying goes in Roussillon, — and no one will dispute it, — "one must be a Catalan to understand Catalan." The Pays-de-Fenouillet, of which St. Paul was the former capital, lies in the valley of the Agly. Saint-Paul-de-Fenouillet is the present commercial capital of the region, if the title of commercial capital can be appropriately bestowed upon a small town of two thousand inhabitants. The old province, however, was swallowed up by Roussillon, which in turn has become the Département of the Pyrénées-Orientales. The feudality of these parts centred around the Château de Fenouillet, now a miserable ruin on the road to Carcassonne, a few kilometres distant. There are some ruined, but still traceable, city walls at Saint-Paul-de-Fenouillet, but nothing else to suggest its one-time importance, save its fourteenth-century church, and the great tower of its ancient chapter-house. Nearer Perpignan is Latour-de-France, the frontier town before Richelieu was able to annex Roussillon to his master's crown. Latour-de-France also has the débris of a château to suggest its former greatness, but its small population of perhaps twelve hundred persons think only of the culture of the vine and the olive and have little fancy for historical monuments. Here, and at Estagel, on the Perpignan road, the Catalan tongue is still to be heard in all its silvery picturesqueness. Estagel is what the French call "une jolie petite ville;" it has that wonderful background of the Pyrenees, a frame of olive-orchards and vineyards, two thousand inhabitants, the Hotel Gary, a most excellent, though unpretentious, little hotel, and the birthplace of François Arago as its chief sight. Besides this, it has a fine old city gate and a great clock-tower which is a reminder of the Belfry of Bruges. The wines of the neighbourhood, the macabeu and the malvoisie are .famous. North of Estagel, manners and customs and the patois change. Everything becomes Languedocian. In France the creation of the modern departments, replacing the ancient provinces, has not levelled or changed ethnological distinctions in the least. The low-lying, but rude, crests of the Corbières cut out the view northward from the valley of the Agly. The whole region roundabout is strewn with memories of feudal times, a château here, a tower there, but nothing of great note. The Château de Queribus, or all that is left of it, a great octagonal thirteenth-century donjon, still guards the route toward Limoux and Carcassonne, at a height of nearly seven hundred metres. In the old days this route formed a way in and out of Roussillon, but now it has grown into disuse. Cucugnan is only found on the maps of the Etat-Major, in the Post-Office Guide, and in Daudet's "Lettres de Mon Moulin." We ourselves merely recognized it as a familiar name. The "Curé de Cucugnan" was one of Daudet's heroes, and belonged to these parts. The Provençal literary folks have claimed him to be of Avignon; though it is hard to see why when Daudet specifically wrote C-u-c-u-g-n-a-n. Nevertheless, even if they did object to Daudet's slander of Tarascon, the Provençaux are willing enough to appropriate all he did as belonging to them. The Catalan water, or wine, bottle, called the porro, is everywhere in evidence in Roussillon. Perhaps it is a Mediterranean specialty, for the Sicilians and the Maltese use the same thing. It's a curious affair, something like an alchemist's alembic, and you drink from its nozzle, holding it above the level of your mouth and letting the wine trickle down your throat in as ample a stream as pleases your fancy. Those

who have become accustomed to it, will drink their wine no other way,

claiming it is never so sweet as when drunk from the porro. "Du

miel délayé dans un rayon de soleil."

……………………………………………………….. "Boire la vie et la santé quand on le boit c'est le vin idéal." Apparently every Catalan peasant's household has one of these curious glass bottles with its long tapering spout, and when a Catalan drinks from it, pouring a stream of wine directly into his mouth, he makes a "study" and a "picture" at the same time. A variation of the same thing is the gourd or leathern bottle of the mountaineer. It is difficult to carry a glass bottle such as the porro around on donkey back, and so the thing is made of leather. The neck of this is of wood, and a stopper pierced with a fine hole screws into it. It comes in all sizes, holding from a bottleful to ten litres. The most common is a two-litre one. When you want to drink you hold the leather bag high in the air and pour a thin stream of wine into your mouth. The art is to stop neatly with a jerk, and not spill a drop. One can acquire the art, and it will be found an exceedingly practical way to carry drink. It is a curious, little-known corner of Europe, where France and Spain join, at the eastern extremity of the Pyrenees, at Cap Cerbère. One read in classic legend will find some resemblance between Cap Cerbère and the terrible beast with three heads who guarded the gates of hell. There may be some justification for this, as Pomponius Mela, a Latin geographer, born however in Andalusia, wrote of a Cervaria locus, which he designated as the finis Gallia. Then, through evolution, we have Cervaria, which in turn becomes the Catalan village of Cerveia. This is the attitude of the historians. The etymologists put it in this wise: Cervaria — meaning a wooded valley peopled with cerfs (stags). The reader may take his choice. At any rate the Catalan Cerbère, known to day only as the frontier French station on the line to Barcelona, has become an unlovely railway junction, of little appeal except in the story of its past. In the twelfth century the place had already attained to prominence, and its feudal seigneur, named Rabedos, built a public edifice for civic pride, and a church which he dedicated to San Salvador. In 1361 Guillem de Pau, a noble of the rank of donzell, and a member of a family famous for its exploits against the Moors, became Seigneur de Cerbère, and the one act of his life which puts him on record as a feudal lord of parts is a charter signed by him giving the fishing rights offshore from Collioure, for the distance of ten leagues, to one Pierre Huguet — for a price. Thus is recorded a very early instance of official sinning. One certainly cannot sell that which he has not got; even maritime tribunals of to-day don't recognize anything beyond the "three mile limit." The seigneurs of Pau, who were Baillis de Cerbère, came thus to have a hand in the conduct of affairs in the Mediterranean, though their own bailiwick was nearer the Atlantic coast. At this time there were nine vassal chiefs of families who owed allegiance to the head. After the fourteenth century this frontier territory belonged, for a time, to the Seigneurs des Abelles, their name coming from another little feudal estate half hidden in one of the Mediterranean valleys of the Pyrenees. The chapel of Cerbère, founded by Rabedos in the twelfth century, had fallen in ruins by the end of the fourteenth century, but many pious legacies left to it were conceded to the clercs bénéficiaires, a body of men in holy orders who had influence enough in the courts of justice to be able to claim as their own certain "goods of the church." Louis XIV cut short these clerical benefits, however, and gave them — by what right is quite vague — to his maréchal, Joseph de Rocabruna. Some two centuries ago Cerbère possessed something approaching the dignity of a château-fortress. An act of the 25th May, 1700, refers to the Château de Caroig, perhaps the Quer-Roig. The name now applies, however, only to a mass of ruins on the summit of a near-by mountain of the same name. Not every one in the neighbourhood admits this, some preferring to believe that the same heap of stones was once a signal tower by which a warning fire was built to tell of the approach of the Saracens or the pirates of Barbary. It might well have been both watch-tower and château. |