| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

PART IV

THE HOMEWARD VOYAGE Continued SAN FRANCISCO TO SOUTHAMPTON By S. R. CHAPTER XXII SAN FRANCISCO TO PANAMA Catching Turtle The Island of Socorro and what we found there The tale of a Russian Finn Quibo Island Suffering of the Natives from Elephantiasis A Haul with the Seine. On the

20th of January, 1916, we left the harbour of San Francisco, and

proceeded to

get well clear of the land, as the glass told us to expect a blow: and

in due

course it came and plenty of it. We hove-to for twenty-four hours,

with oil

bags to wind'ard, for the seas were high and untrue. The weather then

moderated, so we let draw, and put her on her course, and were soon in

a more

pleasant climate. The

Panama Canal had been closed to all traffic for many months past, in

consequence of land-slides. Of course Mana,

drawing but 11 feet, and only 72 feet on the waterline, would

experience no

difficulty in passing, if the Administration would permit her to do so.

But

would it? We had been unable to discover, through any source in San

Francisco,

whether we should, or should not, be allowed to traverse the Canal. The

only

course left open to us was to go to the Isthmus and see what could be

done on

the spot: if we could not get through we must continue onwards to the

S'uth'ard, and go round the Horn. Mr. Gillam and the Owner were quite

keen on

doing so. Mr. Gilliam thought it was only fair to the vessel "to give

her

a chance of showing what a good little ship she was." The crew,

however,

said they were quite satisfied on that point, and after three years of

it,

sighed only for Britain, Beer, and Beauty. So firmly were they

convinced that

our plucky Sailing-master would take her round the Horn, just for the

sake of

doing so, should he chance to come back alone without the Owner, that,

when

they signed on again at Tahiti for the voyage home, it was subject to

the

proviso that the outside passage round Cape Horn should not be taken

without

their consent. So, from

the so-called Golden Gate of San Francisco town, to the real Balboa

gate of the

Panama Canal, sailed we in the pious hope that something would turn up

in our

favour, and believing that it would do so, for Mana is

a "lucky ship." And of course that

"something" did: but other events, not devoid of interest, intervene

and demand recital. At this

point political conditions must be referred to for the due

understanding of our

story. Absurd though it be, the fact remains that, just as England

meekly

allows herself to be bamboozled, robbed, insulted, and defied by one

petty san-culotte province, so do the United

States submit to like treatment from Mexico: the same small 8 that

represents

mathematically the consideration in which an Irishman holds the British

Government, may be said equally to symbolise the degree of respect in

which the

American Eagle is held by the patriots of Mexico. Therefore, argued we,

as the

noble Mexican does not hesitate to pluck the Eagle, whenever that fowl

comes

hopping on his ground, still less will he refrain from depilating the

Lion,

should he want some fur for fly-tying. No, we will give the coast of

Mexico a

good berth. A vessel like the Mana

would, at the moment, have been an invaluable capture for the

"patriots,"

whose acquaintance we had no wish to cultivate. We thought of the

many-oared

row-boats of the Riff coast, and how they could come at speed over the

smooth

windless sea and board us on either quarter. Of course our motor would

have

been in our favour, but, all the same, discretion was perhaps better

than

valour, as we were unarmed. So we decided to keep 200 miles off the

land in

working down the coast of Lower California and Mexico, though it would

have been

better navigation, and more interesting, to have come close in. The

climate was now delightful: smooth water: gentle fair breezes. These

conditions

enabled us to capture all the turtle, and more than all, we wanted.

They were

asleep at the surface: the sea like glass, and heaving rhythmically.

The

undulations of a sea like this are so long, and wide, and gentle, that

one

somehow ceases to regard them as waves, and thinks of the movement of

the water

immediately around the craft as being only a local pulsation. We had

noticed, from time to time, isolated seagulls heaving into sight on the

top of

the swell. Sometimes there would be as many as three or four within

calling

distance from one another. Each seemed to stand on a separate piece of

drift-wood, never two on the same piece. Some seemed occupied with

affairs,

swearing all the time, as seagulls always do; some stood silently on

one leg, a-staring

into vacancy" and thinking on their past. Some preened and oiled their

feathers. We could not understand why there should be drift-wood, all

small,

and all over the place like this, so bore down on a sleeping bird,

when, to our

great surprise, we found that his resting-place was the back of one of

Nature's

U-boats a turtle. Some may think then that all we had to do, if we

wanted a

turtle, was to approach a resting bird, but not a bit of it. If the

bird, for

reasons of his own, flew away from the back of the turtle, the turtle

remained

as before, nor did he ever seem to draw the line at the profanity with

which

his visitor argued some point with the nearest neighbours, but let a

boat

approach, however gently and innocently, and the gull decide to clear,

because

he did not like the look of it even as the bird did so, did Master

Turtle

down with his head and up with his heels, and where he had been, he was

not;

without a splash, or a swirl, or a bubble. If any fail to understand

this

description, he should betake himself to Africa and stalk rhino in high

grass

whilst they have their red-billed birds in attendance scrambling all

over the

huge bodies hunting for ticks. Let but one bird spring up suddenly in

alarm

from a rhino's back, forthwith will occur proceedings that shall not

fail to

leave a lasting impression on the observer. When we

wanted a turtle, however, we went to work in this way. The little 12

ft.

dinghy, having two thwarts and a stern-seat, was lowered from the

starboard

quarter and towed astern. A sharp look-out was kept ahead, and to

leu'ard, for

a turtle asleep on the surface. On one being sighted, the vessel was

run off

towards it. Simultaneously the dinghy was hauled up alongside, and two

of us,

barefooted, dropped into her: she was then passed astern again and

towed. One

man sat in the stern sheets and steered with a paddle, having handy a

strong

gaff hook lashed on the end of the staff of a six-foot boat-hook: the

oarsman

occupied the for'ard thwart with his paddles shipped in the rowlocks.

The

leather of the oars had been well greased previously, so as to make no

sound.

The dinghy silently sped after the ship. On the vessel arriving within

some 50

yards of 22 the turtle, an arm on the quarter deck was waved: the

dinghy

slipped her tow line, the ship's helm was put up, and she edged-off to

leu'ard

away from the fish, whilst the dinghy continued, under the way she

carried, on

the line of the vessel's former course, and therefore straight towards

the

turtle. On the sitter catching sight of the fish, if the boat was

carrying

sufficient way to bring him up to it, he laid aside the steering oar,

and at

the right moment made a sign to his mate, who then gently dipped one of

his

paddles in the water. The boat in consequence made half a rotation,

coming

stern-on to the turtle, instead of bows-on as previously. The oarsman

then saw

the fish for the first time and commenced to back her down with gentle

touches

of his two paddles right on to the top of the fish. Meanwhile the

sitter slid

off the after seat, turned himself round so as to face the stern and

knelt on

the bottom of the boat with his knees placed well under the after seat,

his

chest resting on the transom, his arm outstretched over the water,

rigidly

holding the gaff extended like a bumpkin, with the point of the hook

directed

downwards towards the water, and about two inches above its surface. Now the

old turtle is roosting on the water with the edges of his shell just

awash, his

dome-shaped back rising just clear of it, and his head hanging

downwards in

order that he may keep his brains cool. At the opposite end to his head

is his

tail. This detail may seem unnecessary. But it is not so. It is an

essential

point. When a turtle is surprised he does not express it by throwing

himself

backward head uppermost on to his tail, and show his white waistcoat,

and wave

his arms in depreciation of the interview, but he downs with his head

and ups

with his heels and the tip of his tail, if you are able to recognise

it, is the

last you see of Master Turtle. And when he acts thus he shows much

decision of

character: there is no hesitation: in a moment of time he is absent.

Hence,

when you approach a turtle, you must first decide where away lies his

tail, and

so place your craft that her keel, and the turtle's spine, shall lie in

the

same straight line. Then, as she is backed stern foremost towards him,

the staff

of the gaff is brought, by the movement of the boat, immediately above

the

length of his back. Now for it! the fisherman suddenly thrusts the gaff

from

him till the point of the hook is beyond the rim of the shell: raises

his hand

the least trifle, so as to depress the hook slightly, then savagely

snatches

the gaff backward, at the same time shortening his grasp on the shaft.

The

turtle awakes from his dreams to find that he is in a position in which

he is

helpless standing on his tail, with his back against the boat's

transome, and

his fore flippers out of water. But he is not given time to think. As

his back

touches the flat end of the boat, the fisherman springs from his knees

to his

feet and, with one lusty heave, hoicks Uncle up on to the edge of the

transome

and balances him there for the moment. Down goes the stern of the

little boat,

well towards water level under the combined weight of man and fish.

Then the

slightest further pull, and into the bottom of the dinghy the turtle

slides

with a crash, whilst the fisherman, whose only thought now is for the

safety of

his toes, gracefully sinks down upon the middle thwart, takes hold of

the

gunnel with either hand, and hangs one bare leg overboard to starboard,

and the

other to port, until the turtle has decided in which part of the boat

he

proposes permanently to place his head. Slowly he opens and closes his

bill,

shaped like the forceps of a dentist, and slowly he blinks his eyne, as

much as

to say, "Just put a foot in my neighbourhood or even one big toe."

Turtles have no charity. The

turtle and the fisherman have engrossed one another's attention so far,

but

there are three other elements in the equation; they are (a)

the boat, (b) the

boatman, and (c) the shark. Each of

these requires a word in passing. Now a 12 ft. dinghy, like any other

of God's

creatures, has feelings: these it expresses amongst other ways, when

treated

unreasonably, by capsizing, and turtle catching it puts in the

neighbourhood of

the limit. Not infrequently it happens that the long black fin of a San

Francisco pilot comes mouching around at a turtle hunt, as if to incite

the

long-suffering dinghy to show temper. Hence it is sometimes quite

interesting

to view, from the ship, the sympathetic way in which the oarsman exerts

himself

to humour every whim of the little boat, in order to induce it to

maintain its

centre of gravity during the scrimmage. He quite seems to have the idea

in his

head that, with the shark assisting at the ceremony, a capsize would be

anything but a joke for him. Anyhow, it is all right this time, so we

make for

the vessel, now gently rising high on the top of the swell, anon slowly

sinking

until only her vane is visible. "Lee-Oh!

Round she comes. Let the staysail bide! As she loses her way the

dinghy

shoots up towards her, a line comes flying in straightening coils from

the bows

of the ship and falls, with a whack, across the dinghy's nose. The

oarsman

claps a turn with it around the for'ard thwart, and quickly gets his

weight out

of her bows, by shifting to the middle thwart, before the strain comes.

At the

same time the fisherman nips aft, whilst keeping an eye on Master

Turtle's

jaws, squats on the after seat, picks up an oar and sheers her in

towards the

ship. Then a strop falls into the stern-sheets: the oarsman slips it

over a

hind flipper, one of the dinghy's falls is swayed to him, he hooks it

into the

strop, and up runs Baba Turtle, to be swung inboard the next moment

into the

arms of the Japanese cook, who receives him with a Japanese smile as he

bares

his sniggery-snee. We had now been more than a fortnight at sea. After

a run of

this length we generally found it well to touch somewhere to refresh.

The chart

showed ahead of us the Island of Socorro which we could fetch by edging

off a

little. The Sailing Directions told us it was uninhabited, and rarely

visited:

that there was no fresh water on it, but nevertheless that sheep and

goats were

to be found, and that landing was possible. The early morning of

February the

5th showed its single lofty peak standing out clearly above the lower

mist, and

in a line with our bowsprit, whilst a light breeze on our quarter made

us raise

it fairly fast. In the chart room we pored over the only chart we had,

a small-scale

one, using it for what it was worth to elucidate the Sailing

Directions. These

indicated an anchorage and landing-place on its south-western side:

poor, but

possible: and no outlying dangers. We therefore decided to examine that

coast,

and see what we could find in the way of anchorage and landing

facilities. At

the same time the conversation turned on the apparent excellence of the

place

as a gun-running depot for the Mexican Revolutionaries, and the

exceeding

awkwardness of our position if we suddenly shoved our nose into any

such

hornets' nest. The pow-wow finished, up the ladder we tumbled on to the

quarter-deck, and turned to the island, and lo! round a point was

emerging a

something first appearing as a boat with bare masts then as a boat

with

sails she has presumably come out under oars and is now getting the

canvas on

her. She has seen us making for the island and is clearing out! They

are at the

game, then, after all! Now she grows into a vessel under canvas: now

she fades

away. No ship had we seen since getting well clear of San Francisco. We

could

make nothing of her in the haze and the mirage, for the air was all

a-quiver

with the heat. The general opinion seemed to be that she was a small

schooner

sailing with her arms akimbo, which, with the wind as we had it, was

impossible. Anyhow she was approaching us rapidly in the teeth of the

wind

goose-winged; but anything seems to our mariners possible "in these

'ere

fur'rin parts." But alas for Romance! Gradually she revealed herself

through the haze as a tramp steamer with a high deck cargo. Her black

hull and

black-painted mast tops, as she opened the land and partly showed her

length,

had made her the small boat with bare pole masts: afterwards, when she

shifted

her helm and came towards us bows on, she became the small schooner

running before

a fair wind off the land her light-coloured deck cargo, high built

up, and

white-painted bridge formed the goose's wings extended on either side

of the

black masts, that rose above them, and stood out distinctly against the

sky. We

kept our course. She passed us close to starboard. We ran up our ensign

and

number and asked her to report us, but she took no notice. Only one man

was

seen aboard her. We thought at the time she was from the Canal, but

afterwards

learnt that nothing had come through it for some months, also that a

somewhat

similar vessel had, in May last, lain for a month off Socorro to

.....admire

the scenery. We closed

with the land, at its western extremity, about 3 p.m., and then slowly

ranged

along the south-western shore, examining it carefully with the glasses

for

indications of a landing-place. The water was smooth and crystal-clear,

and the

sun behind us, so that, comfortably ensconced in the fore-top, we could

see

well ahead in the line of the ship's progress, and to a great depth. We

were

able therefore, without risk, to hug the shore, and to examine it with

precision. Everywhere was the same low cliff: on its top, scrubby

vegetation

with a sheen like the foliage of the olive (sage bush). Immediately

below

this a broad scarlet band (disintegrated lava) then a greyish red,

or

black, cliff wall of igneous rock at its foot a snow white girdle of

foam

from the ocean swell dashing against it. So we

progressed, until we reached what we decided must be Braithwaite Bay,

at the S.W.

corner of the island. The Sailing Directions gave this as the only

anchorage.

Mr. Gillam jumped into the dinghy and pulled in to examine it, whilst

we

followed her in very slowly with the ship. A couple of whales seemed to

find

the floor of the bay quite to their taste as a dressing-room. The huge

fellows

quietly spouted and wallowed, a-cleaning of themselves," and took no

notice of us. The dinghy did not like the look of things for either

landing or

anchorage, so held up an oar. Thereupon we put the ship round, and went

out on

the same track as that on which we had entered. Nightfall was now

approaching.

We picked up the dinghy and stood off a bit, and then hove-to. Now,

immediately before reaching Braithwaite Bay, we had noticed in the

coast-line,

from the mast-head, an indentation or small inlet, across which there

was no

line of breakers. Also we had observed a remarkable white patch set

deeply into

the land apparently at the head of this indentation. Of these points

presently.

During the night, whilst hove to some distance off, the watch picked up

a

beautifully modelled painted and weighted decoy duck, with the initials

"H.

T." cut into it. This wooden fowl, we concluded, had drifted down from

San

Francisco, for there they are largely used in duck shooting. It had

broken its

anchoring line, been swept through the Golden Gate, and then by the

prevailing

winds and currents carried to the point where we had picked it up. The

find was

interesting as showing that our navigation was correctly based for

current. With the

daylight we again stood in, this time towards the inlet, and after an

early

breakfast, the cutter was swung out. A breaker of water, a cooking-pot

or two,

a watertight box of food, another containing ammunition, the

photographic and

botanical outfits, and a Mauser rifle in its water-tight bag, were put

into her

and, with five hands, we started off. As we

approached the break in the cliffs we again met our two friends of

yesterday

the whales. They had shifted their ground and were now right in the

entrance to

the cove, so we had to lay on our oars for quite a while, until they

gradually

moved away. It was most interesting to watch the great brutes

comparatively

close alongside, yet absolutely indifferent to, or unaware of, the

boat's presence.

Certainly we kept quiet, and did not allow objects in the boat to

rattle or

roll. Sound waves are transmitted through the water just as they are

through

the air. Each of these fish would have been worth £1,000 at least at

pre-war

prices. Life is full of vain regrets." Our break

in the cliff proved the entrance to a fissure in the land-mass

comparatively

far extending. On either hand it had nearly vertical cliff walls, and

these

again had steep ground above and behind them. It had a regular,

gradually rising

bottom, deep water at the entrance, and at the head a shelving beach of

sand

and small stones, yet steep-to enough to allow the cutter to float with

only

her nose aground. Not a trace of swell: an ideal boat harbour. As it

had no

name, and is to-day undefined in the Admiralty plan of Braithwaite Bay

(cf.

inset on Chart No. 1936), we christened it Cruising Club Cove

dropping the

Royal" for the gain of alliteration. As we lay

off the entrance, waiting for the whales to shift, many, and varied,

were our

speculations as to what the white object, previously referred to as

situated at

the head of the cove, could possibly be. Not till we were close up did

we make

it out. It then proved to be a red-painted boat, covered with a white

sail. Now

a dry torrent bed forms the head of our little fiord. The detritus

brought down

by the torrent is spread out as a small, flat, channel-cut plain, that

meets

the sea with a fan-shaped border. On to this flat the mystery boat was

hauled

up, but only to just above high-water mark. Close to her side was a

grave with

wooden cross. From her bows hung a bottle closed with a wooden plug and

sealed

with red paint. Keenly interested in it all we disturbed nothing, so

that we

might the better be able to piece together the evidence, after

gathering all we

could. She was evidently laid up: practically new: amateur built: her

material

new deal house-flooring boards: flat-bottomed: sharp at both ends (dory

type).

Left as she was, the surf of the first gale from the South would lift

her. They

must have been either weak handed to leave her close to the water's

edge like

that, or else they had been in a great hurry to get away. No painter

and anchor

was laid out to prevent her floating off: no seaman would leave a boat

thus

unsecured. (For there was cordage in her.) Her sail was cut out of an

old sail

of heavy canvas belonging to some big ship. They had ship's stores to

draw

upon. Casting

around, we soon found a track running through the sage-bush scrub.

Following

this trail for a few yards, we came to a large flat-topped rock beside

which it

ran. On this rock stood conspicuously another bottle sealed. The path

now

began to rise sharply, wending betwixt large rock masses: then it

suddenly

terminated in a rift in the cliff face, which formed a high, but

shallow, cave

or grotto. Rough plank seats and bunks were rigged up around, fitted

under or

betwixt the great rocks, some berths being made more snug by having

screens of

worn canvas. In the middle of the floor was a table, and in the middle

of the

table stood a sealed bottle and a box. The box was a small, square,

round-cornered, highly ornamented biscuit-tin of American make: it was

three

parts full of loose salt, bone dry, and on the top of the salt was a

wooden box

of matches, bone dry and striking immediately. We emptied the salt on

to the

table nothing amidst it: we broke the bottle and we found in it a

scrap of

paper. On this was written in ink, a surname, the day of the month and

year,

the full initials of the writer and these words, Look at our Post

Office

here."1 We then returned to the flat rock and broke that

bottle

the message was the same; then to the boat, to find the message in

its bottle

was identical in terms, but written in pencil. Look at our Post Office" But

where was the Post Office? or what was the Post Office? The fragments

of the

broken bottle lay glittering on the grave at our feet. Was the grave

the Post

Office? We had

most carefully examined and sounded the cave, and, after our long

experience of

this class of work on Easter Island, felt fairly satisfied that the

Post Office

was not there. Every fire site we had suspected and inspected: every

sinkage of

the surface. Now we had to decide about the grave. The character of the

vegetation showed that it was old, and had not been disturbed within

the date

stated on the letters. A Spanish inscription in customary form, cut

very neatly

into the arms of the wooden cross, gave simply the name of the dead

man, and

the date. At one time the cross had been painted black. The point

however that

determined us to accept the burial as bona

fide, and not to exhume it as a possible cache, was the fact that

the sharp

edges of the carving of the inscription were smoothly rasped away by

the

driving sand of the shore, in the direction of the prevailing wind, and

to a

degree commensurate with the date incised. And we were right in our

surmises.

Sufficient now to say that he whom the writing told to go to the Post

Office,

was already lying in his own grave elsewhere, with his boots on, and no

cross

at his head. Life is held cheap in Mexico. The

island is said to possess no fresh water. We found no provision made in

the

cave for conserving a supply. Scrambling through the sage-bush we made

for the

dry torrent. Here we found one of the channels had been diverted, and

in it

sunk a well or shaft, some ten feet deep, with fine soil at its bottom.

The end

of a rope just showed for about one foot above the surface of the silt

at the

bottom of the shaft. Near by was a rough cradle and makeshift gear for

gold

washing. They had been here during the rains, and the torrent had

supplied the

washing water. Thinking of a possible sealed bottle placed in the shaft

bucket

at the end of the rope, we left two hands there with orders to follow

the rope

carefully down to its termination and see what was on the end of it.

The cutter

with two hands we sent back to the ship. We and

one hand a Russian Finn who had been for some years on the Alaska

Coast

then set off inland to see what the world was like, and to get a sheep

if

possible. By this time the heat had become very great. The soil

yellow

volcanic ash soaked up the sun's rays and then threw the heat back as

would a

hot brick. Everything was so dry that we marvelled that vegetation

could hold

its own. We saw no form of grass, but the surface was generally covered

with

sage-bush extending from the level of the knee in general to above

one's head

in the bottoms. We had scrambled up the ravine from our pirates cave

and up

the steep ground around it . We now found ourselves on a well-defined

ridge

that ran parallel to the sea, with a breeze, though a hot one, in our

faces,

and a glorious view of sea, coastline, and mountain. Our whales were

clearly

visible far away in the bight to the west'ard, whilst to the nor'ard

lay the

great mass of an unnamed volcano, with its top lost in mists, its sides

sweeping downwards, with typical curvature, till they reach the sea. We

gave

the mountain the name of Mount Mana. It is 3,707 ft. high. Much

information

about it will appear some day. Between

the ridge on which we now stood, and the well-defined foot of Mount

Mana

opposite to us, was a valley some half a mile wide. We made our way

across this

valley as far as the mountain's foot, in order to cut across any

tracks, human

or ovine, that might pass down it, because they would tell us the news,

like a

file of newspapers for all movement on the island would pass along

this

bottom. Here the sage-bush was very strong and high, and we found it

difficult

to get through. It frequently was tunnelled where it was thick,

reminding one

of hippo paths leading to the water. In the present case, however, bits

of the

fleeces of the makers were clinging to the sides of the tunnel. The

only signs

of man were the brass shell of an exploded military cartridge, and a

few heads

and horns of sheep lying where the beasts had been shot. Here and there

along

the course of the valley, masses of black volcanic rock, bare of

vegetation,

rose above the bright yellow soil and its sage-bush covering. The

surface of

the plain and of the mountain's base were also punctuated by isolated

specimens

of a species of fig (ficus cotinifolia)

having a dark green fleshy leaf somewhat like that of the magnolia, and

a

number of separate trunks or stems. These trees, like all else, were

dwarf and

stunted, and about 15 feet high. Every tree formed a flattish roof, as

it were,

supported on many pillars and impervious to the sun. It was delightful

to rest

for a short while under each as we came to it for a brief respite from

the

shimmering heat. Beneath them the ground was bare and smooth. The sheep

tracks

and tunnels led from tree to tree, and it was evident that the sheep

made it

their practice to rest on these shady spots, during the heat of the

day. Whilst

so resting ourselves, we were amused and interested by several little

birds of

different sorts. They chummed up en route, and kept close to us

wherever we

went, flitting from bush to bush, and when we sat down in the shade,

sidled

along the branches till they got as close to us as they could, short of

absolutely alighting upon us. They acted just as native children do

towards the

white man when they have got over their first shyness. Working up wind,

we soon

found sheep; they were in small bunches varying from three to perhaps a

dozen.

We got a couple, though both getting up to the game and the shooting

was

difficult in such cover, and resolved itself into snap-shots as they

followed

their tracks across the occasional isolated masses of dark basalt that

rose

above the yellow soil and which supported no vegetation. Having

gralloched our victims and slung the carcases well up on to our

shoulders, with

both breast strap and brow strap, Micmac fashion, we started back for

Cruising

Club Cove. It was now about noon, and as a direct line seemed feasible,

we

decided to take that line. The better road along the sheep tracks, and

therefore through their tunnels, along the bottom of the valley, was

impossible

for a laden man. We did it! Across the valley, often brought to a

standstill by

scrub that would not yield when leant against. Up the hill side to its

delusive

gap, often on hands and knees. Down the steep pitch on the other side,

with

bump and crash, regardless of scratches, thinking only of how to avoid

a broken

leg or twisted ankle. Then a final wrestle with scrub in the ravine

bottom and

we were on the shore. What a relief to throw up that brow strap for the

last

time and to let the mutton fall, with a thump, on the stones! Then off

with

what remained of our clothes, with which we draped the bushes to dry,

and into

the tepid shallow water, shallow for fear of sharks. Orders were given

that

whilst bathing a good fire of scrub wood should be made on a spot

sheltered

from the sun by the side of a lofty rock. On that fire's glowing

cinders when

nearly burnt out we presently grilled kidneys of peculiar excellence,

and

boiled the billy, and thanked the Immortal Gods. The

examination of the dry shaft, which was the job of the two hands left

behind,

was never made. They reported that soon after beginning work the side

of the

shaft fell in. On looking at it, it was clear that we could not now do

anything

there. So we hunted around again, collecting seeds, and plants, and

rock

samples. Presently, amongst the drift material at storm high-water

mark, we

came across a cube of wood 12 or 15 inches square: (the end of a baulk

of

timber sawn off): through it was bored an auger hole, and a rope rove.

The end

of the rope passed through the block was finished with a "Stopper"

knot, a knot known only to seamen. Its other end had one long single

strand

that had been broken: the other two strands were shorter than the first

by some

two feet. They had been cut through.

The story was clear. We only wanted a name, and mirabile

dictu we have it. Turning over the block, on one face is

deeply cut in letters some three inches long the words ANNIE LARSEN.

Pussy is

out of the bag! For the

benefit of those who are not shippy yachty devils, we will now explain.

When

you drop your anchor at any spot where the nature of the bottom is such

that

you may, perhaps, not be able to lift it again by heaving on the chain

in the

ordinary way, because the anchor has fallen amongst rocks, or into some

mermaid's coral cave, under such circumstances it is customary to

fasten one

end of a rope to the end of the anchor opposite to that to which the

chain is

attached (i.e. to the crown), and to

the other end of the rope you make fast a buoy you buoy your

anchor."

Then, when the sour moment comes" to take a heave, and you have heaved

in

vain, you pick up your anchor buoy, and haul on its rope, and up comes

your

anchor without a struggle, like Cleopatra's red herring. Our find

told us that it belonged to a ship of moderate size, for her anchor was

of

moderate weight, because the anchor rope was of moderate strength; and

that

that ship was probably a sailing ship, because she had no steam winch:

for

steamers don't usually buoy, having immense steam heaving power. She

had not

intentionally left it; the rope had had two strands cut through by the

sharp

rocks of the bottom, then the third strand had torn apart from strain,

and the

buoy, with its short length of rope, drifted away, to be ultimately

thrown up

above ordinary high-water mark during a gale. Like the duck, it might

have come

down from San Francisco! Not so. The two cut strands had not been long

in the

water after they had been cut before they were thrown up high and dry. It was

very compromising for Annie. Of course we immediately asked, "Anyone

know

the Annie Larsen? The Russian Finn,

naturally au courant with all the

coast scandal after a month in San Francisco, was immediately able to

inform us

that the Annie Larsen was an American

schooner of about 300 tons, and was in the Mexican gun-running line

till

captured so laden by a U.S.A. ship of war only a month ago whilst we

were at

San Francisco. So we had

got to the bottom of things after all, though we had failed to find the

Post Office!

Socorro Island was the depot for the late Yankee gun runner Annie

Larsen: the special, little-used

boat was for shipping, not for landing, the stuff: the Mexicans had

come and

fetched it away in their own craft as they got the chance. Some of the Annie Larsen crowd, being old Alaska

hands, had prospected the ravine for gold, Alaska fashion. It was not a

case of

ship-wrecked men on a waterless island. The

afternoon was now getting late: Mana

stood boldly in close to the entrance of the cove. She lowered her

cutter, the

shore party were soon on board again, and at 5.35 p.m. (6.2.16) we bore

away

for Hicaron Island at the entrance to the Gulf of Panama, S. 69° E.,

distant

1,834 miles. As we watched the island fade in the dusk, we thought we

had done

with Socorro for ever; but it was not thus written. Some six months

after our

visit a man was arrested at Singapore as a spy, and there detained in

prison.

That man was the writer of the message in the bottle. In prison he

chanced to

get hold of a piece of a local newspaper, and that particular number

happened

to have in it an account of the voyage of Mana

taken from the London papers. It incidentally mentioned that she had

touched at

Socorro. A ship then had been to his island! What had we found? How

much did we

know? Had we found the Post Office?

On release he made his way to England to find out. But now is not the

time to

tell the story: we are bound for Panama, or for Cape Horn for better

or for

worse for heat or for cold. Chance, however, at this time, all

unknown to us,

had decided our fate. The rainy

season was now approaching, and we even got an occasional warning

shower, which

made us all the more anxious to reach the Isthmus, and get clear of it,

before

its unhealthy season set in. But our progress was slow: we could not

run the

main engine continuously, as we only had a small supply of lubricating

oil

adapted to the great heat. That with which we had been supplied at San

Francisco proved useless. Also we had long before unwisely sent back to

England

the light canvas and all its gear, in order to get more stowage room.

In doing so

we thought we would be able to run the ship under power in light airs,

and

therefore would not want it: 'twas an error. However, we always made

something,

for if she did not do her 50 miles in the 24 hours, we unmuzzled the

motor. Our

engineer, Eduardo Silva of Talcahuano, a Chilean, was a most excellent

young

fellow: always keen and willing: always grooming his three charges, the

engines

of the yacht, the life boat, and the electric light, and ever ready to

run

them, despite the terrible heat in the engine-room. Sometimes when the

big 38

h.p. motor had a fit of the tantrums, because it could not get cold

water from

the sea quickly enough to assuage its body's heat, and he durst not

leave it,

he would eventually appear on deck, as pale as a sheet, and completely

done. On

one such occasion he reflectively remarked, as the two of us looked

down into

the engine-room from the deck, "All same casa del diablo."2

He did not exaggerate. Day

followed day. We gradually gnawed into our 1,834 miles. The Russian

Finn came

to the fore as a keen sportsman: from tea-time to dusk he was generally

to be

found somewhere outside the vessel's bows: sometimes on the bowsprit

end,

sometimes standing on the bob-stay, regardless of the fact that a shark

was

very frequently in attendance on us in the eddy water under our

counter.

Looking over the taffrail you could see the brute weaving from side to

side as

does a plum-pudding carriage dog at his horses' heels. One experienced

a sort

of fascination in watching these great fish at night, their every

movement

displayed by the luminosity of the water, until they themselves, on

occasion,

seemed to glow with the phosphoric light. Mana

in these waters generally had shoals or companies of small fish in

attendance

on her, amongst which were always a few larger ones. We got to know

individuals

by sight. We thought they kept to her for protection. It certainly was

not for

what they could get off her copper. With that we never had any trouble:

it kept

as bright as gold. One night

we were asleep on the locker in the deckhouse companion, and were

awakened by

an unholy struggle and crash. Nipping out, we found the Russian on

lookout

for'ard, regardless of the sleepers below him, had leant over her bows

and had

actually hoiked out with a gaff-hook a large porpoise. It seemed

impossible to

believe that a man could have had the physical strength to hoist such a

mass

bodily out of the water, up her high bow, and over the rail. He seems

to have

fairly lifted it out, by the scruff of its neck, as it rushed alongside

after

the fish. He only

fell overboard once: that was on the voyage from the Sandwich Islands,

when we

were not aboard. On reaching San Francisco he brought a note from Mr.

Gillam to

us at our hotel to report arrival. We of course inquired as to their

voyage.

The Russian said it had been quite the usual thing: nothing had

happened out of

the common. Long afterwards he casually informed us that on that run,

when he

went forward one night from the quarter deck to the galley to make the

coffee

for the change of watch at midnight, he went first to do some job on

the

top-gallant-fo'c's'le hedd, and got knocked overboard. En route to the

land of

never-never he found the weather jib-sheet in his hand, and by it was

able to

haul himself aboard again. As he was supposed to be in the galley, he

would

never have been expected to show for half an hour, and therefore would

not have

been missed until the watch mustered. It did not seem to occur to him

that he

had had a bit of a squeak. He did not get wet, so nobody knew, for he

told no

one. As an angel, perhaps there was a certain amount of black down

underneath

his white plumage, but as an A.B. one wished for no better. He was the

second

of Mana's company to be killed by the

Huns after our return. After

heaving-to like this, to let the reader into some of the little humours

of our

domestic life, we must get under way again. Well, everybody seemed

quite happy

and contented "on this ere run": fish, birds, weird ocean currents

and their slack water areas with accumulated drift, sail-mending,

turning out

and painting the fo'c's'le, with life on deck, instead of below, for a

few

days, a threatened blow that never reached us, but only sent along its

swell to

justify the actions of the glass, and the ever-varying incidents

associated

with life on a small craft in unfrequented tropical seas, for we never

saw

another sail, made us so forgetful of the flight of time, that it

seemed that

we had but left Socorro, before we found ourselves off Hicaron Island,

our

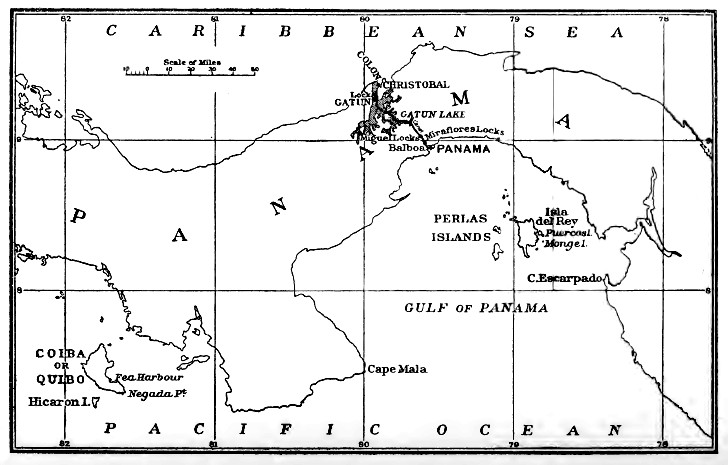

prearranged landfall. Thirty-one days had faded away like a dream (map,

facing

p. 359). Now,

close to the Island of Hicaron lies another one much larger. We had a

plan of

it, Coiba or Quibo Island. The Sailing Directions said "turtles abound,

but they are hard to catch." (We didn't want any more turtle!) "Crabs,

cockles, and oysters are plentiful. In the woods monkeys and parrots

abound,

and in Anson's time, 1741, there were deer, but the interior is nearly

inaccessible, from the steepness of the cliffs and the tangled

vegetation:

explorers should beware of alligators and snakes." The chart showed an

excellent anchorage and indicated fresh water. It seemed promising: we

would

see what it was like. We were particularly desirous of now making good

our

expenditure of water, as we did not know what were the conditions we

might find

prevailing at Panama both as regards its quality and the facilities for

getting

it. We had

sighted Hicaron Island at daylight on Monday, the 6th of March, 1916,

but

calms, baffling airs, and currents prevented our making our proposed

anchorage

by daylight. At dusk, therefore, we hove to for the night. Festina

lentiter was ever our motto. We had the most recent chart

certainly, but its last correction was in 1865 and coral patches grow

quickly.

Not until noon next day did we get abreast of Negada Point, the S.E.

extremity

of Ouibo Island. As the coast was charted free from dangers, we came

fairly

close in, and starting the motor about one o'clock, ran along the shore

under

power, with a lookout in the fore-top. It was

very interesting and pleasant, after a month at sea, thus to coast

along the

fringe of a tropical island: sweeping round rocky points of the land,

and

peeping into lovely little coves fringed with white coral sand that

merged into

a dense tropical vegetation, with hills in the background. It soon

becomes

instinctive to keep the sharpest of look-outs ahead, i.e.

into the clear water, for a change of colour indicating

danger, and yet to see everything around. The most memorable feature of

this

particular afternoon was the large number of devil-fish that were seen

springing into the air: as many as three or four might be observed

within as

many minutes. Suddenly, near or far, a large object, like a

white-painted

notice-board, shot vertically into the air to considerable height, to

fall back

again on its fiat with resounding spank and high-flying spray, leaving

a patch

of milky foam on the smooth blue surface of the water. In British seas

this

family of fishes is represented by the skate. Here they attain the

dimensions

of a fair-sized room: a specimen in the British Museum from Jamaica

measures 15

ft. by 15 ft. and is between three and four feet thick, hence the

statement

that "their capture is uncertain and sometimes attended with danger"3

is probably not far from correct. Perched aloft, and thus having a

large and

unobstructed horizon, we saw one jump probably every ten minutes

throughout the

afternoon. The motor brought us to our anchorage, and at 5 o'clock we

let go in

9 fathoms, sand and mud, the shore distant about 1½ miles.

We had

seen hitherto no sign of the island being occupied, nor did we now.

After dark,

however, at two widely separated points, a fire blazed up and lights

showed for

a short while. Smoking on deck, when dinner was finished, we speculated

as to

the meaning of the different mysterious grunts and gurgles, sighs and

plunges,

that stole over the tepid oily water: the tropical sea after dark

seemed to

have voices as many and varied as the tropical forest has when the sun

is gone.

From 6 p.m. onward the thermometer read 87° F.: at 6 a.m. it had fallen

to 83°

the cool of the morning! With the

daylight a single pirogue, with two men in her, came alongside. She was

a small

and roughly made dug-out, very leaky. In the wet of her bottom lay a

bunch of

bananas, perched on which were a couple of large macaws. Each of these

had a

strip of bark some two feet long tied to its leg. The bunch of bananas

lay like

an island above the water in her: on to it as a refuge the parrots

crawled.

Their jesses entangled amongst the bananas the boat rolled so did

the

banana bunch each bird would climb upwards, but he could not, the

accursed

thong held him down: he was being crushed, he was being drowned he

and his

mate. And each said so. An American mining captain taking up his

parable was

not in it with those birds for language. The two

men were negroid in feature. One of them had only one leg, and seemed

sad and

ill. The other was more cheerful. We could get along together in

Spanish. They

invited us to come ashore. Hoisting out the cutter, we followed them

in. Their

lead was useful, as the water is so shoal. Though the rise and fall is

but

small feet, yet a large area of coral rock fiats is dry at low water on

either

side of a boat channel. At the entrance to this channel an open sailing

boat,

some 25 feet long, their property, lay at anchor. As the tide was

falling, we

thought it best to leave our cutter at anchor in sufficiently deep

water for

her not to take the ground, and got our friends to ferry us from her,

one by

one, into shoal water in their canoe. It was most comic to see some of

our big

chaps kneeling on the bottom of the crazy little craft with a hand on

either

gunnel, whilst they bent forward, like devout Mussulmans on their

carpets,

endeavouring to get their centre of gravity as low as possible. We were

the

last of the passengers. When the water got to be only knee deep the

native

anchored his canoe, and we stepped overboard. So did our one-legged

ferryman.

His right hand controlled a crutch, in his left he held various

treasures

obtained from Mana; he also desired

to take his two big parrots ashore, so, as the last item of all, he

hooked his

finger under the cord that tied them together, thus carrying them

swinging

heads downwards. But apparently he had not taken the cord fairly in the

middle.

One parrot was suspended by a short length of line: the other by a

long: he of

the short cord was able to twist himself round and get a hold with his

beak on

some package in his owner's hand, and was thus reasonably happy. But

parrots,

like ourselves, can't have it all ways in this world of woe. If his

head be up,

his tail must be down: hence this tale. He of the long string found

himself

draggling in the water with every stride of his one-legged owner. In

his

struggles to avoid drowning by a succession of dips, he managed at last

to

grasp, with beak and claw, the long dependent tail of his fellow

prisoner, and

quickly hauling himself up it, heat once proceeded to consolidate his

position,

by seizing in his beak the softest part of his colleague's hinder

anatomy with

the vice-like grip of despair, and therefrom he continued to depend in

placid

comfort, regardless of the other's piercing shrieks and protestations. It is not

always those at the top of the ladder that have the best time of it. A wide

shore line of white sand met us. On it at high-water mark were large

quantities

of white bleached driftwood trees. On the flat ground behind, beneath a

dense

tree growth, were some small pools of stagnant rain water, a few

coconut palms

were dotted about all else was jungle. On a patch cleared of

undergrowth

stood a light frame structure open on all sides. The roof was high

pitched and

had wide eaves: there was no attempt at a floor. It might be 30 ft. by

20 ft.

Smaller similar structures adjoined for cooking and stores. A box or

two,

baskets, hammocks, and a little boat-gear, were suspended from the

beams above:

a few wooden blocks for stools were on the earthen floor, which was

neatly

swept. On one such sat a terribly afflicted specimen of humanity the

mother,

yet nevertheless dignified and courteous. The father, a spare little

man with

an intelligent face, lay in his hammock and extended his hand feebly

over the side

simply saying that he was "infirma." He seemed to avoid making any

movement. Four or five children of various ages moved listlessly about;

only

one of them, a girl of ten or twelve years of age, seemed quite

healthy. Then

there was the one sound man from the pirogue and the cripple. The whole

family

were being slowly destroyed by fever and elephantiasis, and apparently

must,

before long, perish from lack of ability to gather food. No resources

were

visible though no doubt they had a little cultivated ground somewhere

handy^ and

of course there was always fish. The whole story of gradually

encroaching

disease and suffering was so easy to read, and the patient and hopeless

resignation with which the little group awaited its predestined

extinction was

very pathetic. They uttered no complaint nor asked for anything. We

made the

best of things, and got them quite cheerful and interested, producing

from time

to time various trifles from our pockets which we generally carried

with us as

presents when going ashore. Anxious to please, they gave us various

quaint

shells and a little fruit, and again pressed on our acceptance the

hapless

macaws, now secured to a handy branch, whose bedraggled plumage and

sorry mien

seemed quite in keeping with the surroundings. Altogether our visit

seemed to

give our hosts pleasure. The man appeared to have some Spanish blood in

him and

to have known better days. We then returned to the ship, and had

breakfast,

sending back by the pirogue, which had returned with us, a little

present of

ship's biscuit, tinned meat, cigarettes, and quinine. It was obvious

that no

watering was feasible at this landing-place. They told us we should be

able to

get water at the other spot where we had seen a light the evening

before. Pulling

in the heat and sun any considerable distance was out of the question,

so we

hoisted out the motor lifeboat launch, taking the cutter in tow for

landing. We

found another wide sandy beach, but with fairly deep water right up to

it.

There was sufficient breaking swell on it to require the cutter to be

hauled up

smartly, directly her nose touched, or the next sea would have knocked

her

broadside on and filled her. The shore was bordered by what appeared to

us,

from its state of neglect, to be a deserted coconut plantation. We

however told

the men not to swarm up for nuts for the present there are generally

some low

easily climbed trees until we found out how the land lay. The white

man never

seems to be able to understand that petty plundering of native

plantations is a

bad introduction. Needless to say that it was not many minutes before

the

irrepressible Finn had "found on the ground" a bunch of green nuts

and was devouring them with the avidity of a land crab. Foot-prints on

the

shore, and trails through the scrub, soon brought us to a group of

shanties

under the palm trees, and therefore close to the shore line. The

coconut palm

seems to thrive best just beyond high-water mark, and on any flat at

about that

level behind the furthest point reached by the water. Trees are often

to be

seen with the soil round their roots partially washed away on one side

of the

trunk. A white

man came walking along the shore to meet us. Of course the first thing

we did

was to apologise for the unseemly sight of the men all feeding on his

nuts. He

was fairly cordial, but evidently greatly perplexed as to who, and

what, we

were. We told him as well as we could about the ship and the reason of

our

visit, but it was obvious he thought we lied. All the same he gave us

the

information we wanted as to supplies and water. Practically nothing was

to be

had. As it would be shortly our men's dinner hour, we persuaded him to

come

with us aboard, and he thawed considerably under the influence of

luncheon. He

told us the coco palms had been planted by his father, and that his

name was

Guadia. The Sailing Directions, as to this place, are quite wrong.

Moreover,

they seldom quote their authority, or the date of the information they

give,

which renders them very untrustworthy. About

twenty fever-stricken natives, many of them cripples from

elephantiasis, live

here permanently on the plantation under the flimsy shelters. Sr.

Guadia said

he lived usually in the city of Panama, but came over for some months

during

the healthy season, occupying a somewhat superior hut in the midst of

the

native shacks. There are comparatively high hills close to hand, that

would be

infinitely more healthy as a residential site. He will probably get

infected

from the natives. The mosquitoes pass the disease along. As the

watering scheme had broken down, we thought we would devote the

afternoon to

fishing. Sr. Guadia said that, if we really wanted fish, we ought to go

to the

mouth of a river some distance away, but that the bottom was all clean

opposite

his camp, so we thought we would take a few drags of the seine along

his front.

We faked it down into the cutter and the launch towed her in. All along

the

beach the water was almost soup-like from the mud in suspension, also

in it

floated, in immense quantity, tiny fragments of fine marine grasses,

the whole

being kept constantly churned by the swell. In this opaque water fish

could not

see the net. Casting off from the launch the cutter backed into the

beach: one

hand jumped ashore with the head and foot ropes. She then described a

semicircle as she shot her net: our seine was 50 fathoms long and 2

fathoms

deep: as she completed the semicircle by touching the beach the spare

hands

jumped ashore with the other head and foot ropes and the boat pulled

away to

the launch to land that party, for without them it was impossible to

haul the

net: the resistance was far too great. The natives the whole

population of

the huts grouped themselves together at a little distance, but never

offered

to lend a hand. At last we got a move on the net, but the resistance

was

excessive, and we were afraid that she had picked up something.

Gradually

however the line of buoying corks rose to the surface as the leaded

foot rope

took the ground, defining the semicircle with a row of dots, whilst

over them

jumped, at various points of the most distant part of the curve, a

multitude of

small fry, like a stream of silver darts, and with rain-like patter as

they

struck the water. Gradually the escaping captives became larger and

larger,

springing high into the air, and we thought that we should find but

little left

when we got the net ashore, for the weight in it was such that we could

move it

but slowly. Keep her up! Keep her up!" was now the cry, to

counteract

the tendency to haul on either head rope or foot rope unduly in the

excitement

of the finish for a seine is simply a moving vertical wall of net,

and must

be maintained as such in use. At last the contained area began to

simmer: then

to boil: and then, still hauling evenly, we brought the mass more or

less upon

and against the sandy beach. Practically it was solid fish: fish of

every size,

shape and colour. There was comparatively little weed. By their very

number

they had been rendered helpless. This was great good luck, for amongst

them was

a large shark some ten or perhaps twelve feet long, and another brute

of about

the same size and weight, but he chiefly consisted of head, and his

head

chiefly consisted of mouth. When this mouth, with two little eyes at

the sides,

looked at you, the shark seemed of benevolent appearance. Of course

our first thought was for the safety of the net; that it was not burst

or torn

already seemed a miracle. The struggles of the two great brutes would

tear it

to pieces if we tried to haul them right ashore, so we just held them

jammed

against the sloping beach. The natives then cautiously ventured to

attack them

with their machettes a powerful slashing knife, like a small sabre,

used for

clearing the forest growth. They directed all their efforts to slashing

them

along the spine: gingerly approaching the fish by the head, they

inflicted the

wounds nearer and nearer towards the tail. Having paralysed that, they

then

blinded them. They did not desire to kill: they wanted the fish to have

enough

life left in it to be able to struggle away.  Having

thus paralysed our two largest captures, we slipped a bowline round

their

tails, and dragged them clear of the net, and started them off, when

they were

at once torn to pieces by their fellows. We then proceeded to collect

the

useful part of the catch. We took what we wanted: the natives

appropriated the

rest. These natives were not an attractive lot neither the men, the

women,

nor the children they would not lend a hand to haul, got three

quarters of

the catch for picking it up, and then tried to steal the balance that

we had

reserved. Sr. Guadia gave us some coconuts, and the antlers of a deer

that he

had shot: according to him they are plentiful on the island. As we

didn't want anybody to get bitten by mosquitoes, and sunset was

approaching, the

order was now All aboard the lugger! and we reached the ship as her

riding-light ran up. 1 We had

intended to reproduce this note in facsimile, but subsequent events

have led us

to think that to do so might cause danger to its writer. 2 Casa =

Sp. house. 3 Cf. Ency. Brit. Edn. 1911, Vol. xxiii., p. 930, Article Ray. |