| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

PART III

THE HOMEWARD VOYAGE EASTER ISLAND TO SAN FRANCISCO CHAPTER XX PITCAIRN ISLAND Lieutenant Bligh went to

the Pacific in 1788,

in command of H.M.S. Bounty,

with orders to obtain plants of the bread-fruit, and introduce it into

the

English possessions in the West Indies. He spent six months at

Tahiti, collecting the

fruit, and there the crew fell victims to the charms of its

lotus-eating life,

its sunshine, its flowers, and its women. Soon after the ship sailed

the

majority of the men mutinied, being led by Christian, the Master's

mate. They

set Bligh and eighteen others adrift in an open boat, and returned in

the ship

to Tahiti. Subsequently, fearing that retribution might follow.

Christian and

eight fellow mutineers left Tahiti on the Bounty,

taking with them nine native women, and also some native men to act as

servants. For years their fate remained a mystery. The refuge found by the

party was the lonely

island of Pitcairn. They took out of the ship everything that they

required,

and then sank the vessel, fearing that her presence might betray them.

The new

habitation proved anything but an amicable Eden. The native servants

were ill-treated

by their masters, and in 1793 rose against them, murdering Christian

and four

other white men; but were finally themselves all killed by the

Europeans. The

women also were discontented with their lot, and in the following year

they

made a raft in order to quit the island, an attempt which was of course

foredoomed to failure. Of the four mutineers left,

one, McCoy,

committed suicide through an intoxicating drink made from the ti plant.

Another, Quintal, having threatened the lives of his two comrades,

Adams and

Young, was killed by them with an axe, in self defence. A woman who

witnessed

the scene as a child, survived till 1883, and we were told by her

grandchildren

that her clearest recollection was the blood-spattered walls and the

screaming

women and children. Young, who had been a midshipman on the Bounty, died shortly after,

and in 1800 John Adams

(alias Alexander Smith) was left the

sole man on the island, with the native women and twenty-five children.

Later ensued not the least

strange part of

the story. Adams was converted by a dream, and awoke to his

responsibility

towards the younger generation. He taught them to read from a Bible and

Prayer-book saved from the Bounty,

and the offspring of the mutineers became a civilised and God-fearing

community. The small colony were first

found by an

American ship, the Topaz,

in 1808, but little seems to have been heard of the discovery, and six

years

later H.M. ships Briton and Tagus,

sailing near the island, were much

astonished at being hailed by a boat-load of men who spoke English. By 1856 the population of

Pitcairn numbered

about one hundred and ninety, and they were removed, by their own

request, to

the larger Norfolk Island. Six homesick families, however, against the

strong

advice of Bishop Selwyn, subsequently returned to Pitcairn. In the

afternoon of Wednesday, August 18th, 1915, the last vestige of the long

coast

of Easter Island dipped below the horizon. We realised that we were

homeward

bound. Owing to the war, and our prolonged residence on the island, it

was no

longer possible to keep to the plan made before leaving England and

follow up

Easter trails elsewhere in the Pacific. We decided, however, to adhere

to the

original arrangement of going first to Tahiti, and then to make the

return

voyage by the Panama Canal, which was now open. One of our principal

objects in

visiting Tahiti was to collect all the letters, newspapers, and money

which had

been forwarded to us there during the last twelve months. With the

exception of

one stray letter, written the previous November, we had had no mail

since

Mmia's first return to the island a year before. It seemed desirable to

visit

Pitcairn Island on the way thither; it was but little out of our route,

and was

said to have prehistoric remains. We had a

very good voyage for the 1,100 miles from Easter to Pitcairn,

staggering along

with a following wind. The wind was indeed so strong that we became

anxious for

the safety of the dinghy in her davits, and swung her inboard for, I

believe,

the only time on the voyage. We arrived at Pitcairn on August 27th. The

island,

as seen from the sea, rises as a solitary mass from the water. It is

apparently

the remaining half of an old crater, and is some two miles in width. An

amphitheatre of luxuriant verdure faces northwards; its lowest portion,

or

arena, is perhaps 400 feet above sea level, and rests on the top of a

wall of

grey rock. The other three sides of the amphitheatre are encircled by

high

precipitous cliffs. The green gem, in its rocky setting, was a

refreshing

change after treeless Easter Island.  FIG. 126. — PITCAIRN ISLAND FROM THE SEA.  FIG. 127. — PITCAIRN ISLAND: CHURCH AND RESIDENCE OF MISSIONARIES.  FIG. 128. — PITCAIRN ISLAND: BOUNTY BAY. Mana was welcomed by a boat-load of sturdy

men, who

were definitely European in appearance and manner; they were mostly of

a sallow

white complexion, though a few had a darker tinge. They spoke English,

though

with an intonation different from that of the Dominions, America, or

the

Homeland. A local patois is sometimes used on the island which is a

mixture of

English and Tahitian, but pure Tahitian is not understood. A graceful

invitation was given by the Chief Magistrate, Mr. Gerard Christian, to

come and

stay on shore, and was accepted for the following day, which, the

Islanders

said, "will be the Sabbath." This was a somewhat surprising

statement, as the day was Friday, and caused a momentary wonder whether

something had gone wrong with the log of Mana.

“We will explain all that later," added our hosts. The next

morning therefore the big ten-oared boat turned up again, Mr. Christian

bringing us the following kind letter from the missionaries, who we now

learned

were on the island. It was addressed "To the Gentlemen concerned." Pitcairn

Island.

27.8.1915. "Dear

Sir and Madam, "It

is with pleasure that we extend this invitation to you to share with us

the few

comforts of our little Island home. We cannot offer luxury, we live

simply yet

wholesomely. Should you be planning to sleep ashore, it will be well to

bring

your pillows, towels and toilet soap. We trust that your stay will be

attended

with success. "Yours

very cordially, "Mr.

and Mrs. M. R. Adams." We

suggested bringing food, but that was declined as unnecessary. The trip

to the

shore, even in so big a boat, is somewhat adventurous. The

landing-place is in

Bounty Bay, below the precipitous cliffs off the north-east corner of

the

island, beneath whose waters were sunk the remains of His Majesty's

ship. The

shore is reached, even under propitious circumstances, through a white

fringe

of drenching surf; happily the Islanders are excellent oarsmen, for the

boat is

apt to assume the vertical position usually associated with pictures of

Grace

Darling. A lifeboat sent as a gift from England in 1880 has proved too

short

for the character of the waves. The village is gained by a steep path,

cut at

times in the rock, and at the summit we found standing under the trees

a group

in white Sunday attire waiting to welcome us. We were

now beginning to understand the meaning of the difference in days.

Service used

to be held at Pitcairn after the manner of the Church of England, but

in 1886

the island was visited by one of the American sect calling themselves

"Seventh Day Adventists." The Society is Christian, but the members

regard as binding many of the Old Testament rules. Saturday is observed

as the

divinely appointed day of rest, pork is considered unclean, and a tenth

part of

goods is set aside for religious purposes. Special attention is paid to

Biblical prophecy, and the end of the world is thought to be near. It

was not

difficult to convert the reverent little community on Pitcairn to views

for

which it was claimed that they were the plain teaching of the Bible,

and

various persons were shortly baptised in the sea. The group

who awaited us were headed by our most kind hosts, the missionary and

his wife,

Mr. and Mrs. Adams, who were of Australian birth.1 Sunday

school was

just over and service about to begin. It was held in an airy building

filled

with a large congregation. The sermon was on prophecy as found in the

books of

Daniel and Revelation, and fulfilled in the division of the Empire of

Alexander

the Great. It was depressing to be told that the late war is only the

beginning

of trouble. We went

back with Mr. and Mrs. Adams to luncheon, which was served at 2.30, and

composed principally of oranges and bananas. It was a very dainty if,

to some

of us who had breakfasted at 7 o'clock, a rather unsubstantial repast.

Our

hosts were vegetarians and had only two meals a day, but subsequently

kind

allowance was made for our less moderate appetites. I was glad of a

rest in the

afternoon, but S., who attended a second service, said it had been the

most

interesting part of the Sunday observances; it was a less formal

gathering,

when personal religious testimonies were given by both young ana old.

Later we

were shown a little settlement of huts in the higher part of the

island, where

once a year the community retire for ten days and have a series of camp

meetings. The

teachings of the new religion are practically observed. The tithe barn,

at the

time of our visit, held £100 worth of dedicated produce which was

awaiting

shipment. It was the prettiest sight to see the fruits of the earth,

being

brought into it, in the form of loads of various tropical produce. The

whole

community abstains from alcohol and, nominally at any rate, from

tobacco,

though one old gentleman was not above making an arrangement for a

private

supply from the yacht. Tea and coffee are thought to be undesirable

stimulants,

and even the export of coffee was beginning to be discouraged. The

place

suffers admittedly from the social laxity characteristic of Polynesia;

but the

evil is being combated by its spiritual leaders, and is cognisable by

law. The

whole atmosphere is extraordinary; the visitor feels as if suddenly

transported, amid the surroundings of a Pacific Island, to Puritan

England, or

bygone Scotland. It is a Puritanism which is nevertheless light-hearted

and

sunny, without hypocrisy or intolerance. The

general influence of the missionaries seemed very helpful to the little

community, and they also conducted a school for its younger members.

Most of

the inhabitants can read, but the subject matter of books is too far

away for

them to be of much interest, and the only application, it was noticed,

which

was made to the yacht for literature, was for picture papers of the

war. We

gave by request an hour's talk on the travels of the Mana,

and it was listened to with apparent understanding, or at any

rate with politeness; the chief interest shown was in the manner of

life of the

Easter Islanders, about which many questions were asked. The

houses are substantially built of wood with good furniture. A well-made

chest

of drawers was a birthday present to the missionary's wife from the

young men

of the island. There is a separate bedroom or cubicle for nearly every

inhabitant, and some houses have a room set apart for meals.

Hospitality was

shown without stint, and we were entertained during our stay to a

series of

attractive repasts in various homes; our hosts bore such names as

Christian,

Young, and McCoy. Meat is limited to goat or chicken, but there is a

profusion

of tropical produce, and oranges are too numerous to gather. The

coconut trees

are unfortunately dying. Each household has a share of the ground

rising behind

the village, and the hillside is traversed by shady avenues of palms

and

bananas, which afford at every turn glimpses of outstanding cliffs and

the

brilliant blue of the ocean. The standard of life compares very

favourably with

that of an English village, and is immeasurably superior to that

achieved on

Easter Island under similar circumstances. Pitcairn

has the dignity of being a democratic self-governing community, with a

Magistrate and two houses of legislature. The present Constitution was

suggested by the Captain of H.M.S. Champion in 1892, and superseded an

earlier

one. The Lower House, known as "the Committee," comprises a Chairman

and two members, also an official Secretary; it makes regulations which

are submitted

to the Upper House or "Council." The Council consists of the Chief

Magistrate, with two assessors and the Secretary, and it acts also as a

court

of justice. The two committee members and a constable are nominated by

the

magistrate, but the other officials are elected annually by all

inhabitants

over eighteen years; Pitcairn was therefore the first portion of the

British

Empire to possess female suffrage. It was

interesting to see the Government Records, though the present book does

not go

back beyond above fifty years, earlier ones having apparently

disappeared. This

contained the Laws of 1884 revised in 1904; regulations for school

attendance;

a category of the chief magistrates; a chronicle of visits from

men-of-war and

mention of Queen Victoria's presents, consisting of an organ in 1879

newly

minted Jubilee coins received in 1889. There were also recorded the

births,

marriages, and deaths of the island since 1864; and a description of

the

various brands adopted by respective owners for their goats, chickens,

and

trees. Among the

legislative enactments was more than one concerned with the

preservation of

cats, the object being to keep down rats. Thus the laws of 1884 direct

that: "Any

person or persons after this date, September 24th, 1884, maliciously

wounding

or causing the death of a cat, without permission, will be liable to

such

punishment as the Court will inflict. . . . Should any dog, going out

with his

master, fall in with a cat, and chase him, and no effort be made to

save the

cat, the dog must be killed; for the first offence — fine 10s. Cats in

any part

of the island doing anyone damage must be killed in the presence of a

member of

Parliament." Illicit

medical practice is forbidden, and the regulation on this head runs as

follows: "It

may be lawful for parents to treat their own children in case of

sickness. But

no one will understand that he is at liberty to treat, or give any dose

of

medicine, unless it be one of his own family, without first getting

licence

from the President. Drugs may not be landed without permission." More

recent laws enact, that each family may keep only six breeding nannies;

and

that coconuts may only be gathered under supervision of the Committee

or in

company with their owners of the same patch, in case of want, however,

they may

be plucked for drinking. Persons killing fowls must present the legs

(i.e. the

lower portion which bears the brand) to a member of the Government. With the

entries of deaths are recorded their known, or presumed, cause; those

occasioned by accident are somewhat numerous, and include fatal results

from

climbing cliffs after birds, chasing goats, and falling from trees.

Wills can

be made by simply writing them in the official book, but entries under

this

head were not numerous. The

island is in the jurisdiction of the British Consul at Tahiti, but the

Magistrate explained sadly that it was then two years since it had been

possible for his superior to send any instructions. In very serious

matters,

such as murder or divorce, reference is necessary to the High

Commissioner at

Fiji, and five years may elapse before an answer is received. It is

indeed comparatively simple to communicate from Pitcairn with the

outside

world, particularly now that it lies near the route from Panama to New

Zealand.

Warning of the approach of a vessel is given by the church bell, and

all hands

rush forthwith to launch the boat and pull out to the ship. It is

reported that

once the bell sounded whilst a marriage was being celebrated, the

crowded

church emptied at once, and the bride, bridegroom, and officiator were

left

alone. Sooner or later a letter can thus be handed on board, but to

obtain a

reply is another matter; no steamer will undertake to deliver

passengers,

goods, or mails to the island. It does not pay to spend time over so

small a

matter, the liner may pass in the night, or the weather at the time may

render

communication with the shore impossible. During our visit notice was

given that

a ship was approaching; the men, who were at the time engaged in

digging for

the Expedition, threw down their tools and the boat started for the

vessel,

only to founder among the breakers of Bounty Bay. The place is too

remote to be

visited by the trading vessels which visit the Gambler Islands, and as

there is

no anchorage, it is by no means easy for the Islanders to keep any form

of ship

on their own account. In normal times a British warship calls every

alternate

year, but its visits were suspended during the war. Of the two islands,

Easter,

which has at least definite bonds with a firm on the mainland, is on

the whole

the easier of access. The

economic problem of Pitcairn lies in the difficulty of making it

self-supporting. Food and housing materials abound, but clothes, tools,

and similar

articles must be obtained from elsewhere; while to secure in return a

market

for its small exports is almost impossible. It is sometimes said that

as the

result, the inhabitants have grown so accustomed to be objects of

interest and

charity, that they have become pauperised and expect everything to be

given

them freely by passing ships. This was certainly not our experience.

They made

us a large number of generous gifts, such as bundles of dried bananas

and

specimens of their handiwork — hats, baskets, and dried leaves,

cleverly

embroidered and painted. On the other hand they took with gratitude any

articles which were given by us, either as presents or in return for

the things

we purchased. One request has been received since we left the island;

it was

made with many apologies by the Chief Magistrate, and was for a Bible

of the

Oxford Teachers' Edition. The

position, however, is unsatisfactory, and it seems very desirable that

if

possible more frequent communication should be established. In any case

it is

to be hoped that now peace reigns, a warship may visit the place at

least once

a year. It is

frequently suggested that the Pitcairners must have deteriorated in

physique by

intermarriage; as far, however, as we were able to observe, such is not

the

case. It has been remarked, indeed, that a large number have lost their

front

teeth, but in this they are not unique. Dr. Keith observes, in the

report

previously alluded to, that many Pacific Islanders are extremely liable

to

disease and loss of teeth. The effect of such disease is, he states, to

be seen

in every one of the skulls from Easter regarded as belonging to a

person of

over twenty-five years; "tooth trouble is even more prevalent in Easter

Island than in the slums of our great towns." We were asked

to collect pedigrees on Pitcairn and make observations from the point

of view

of the Mendelian theory; this would, however, have been a very long and

troublesome business, and we did not feel assured that the results

would be

sufficiently exact to justify it. While there has possibly been no

fresh

infusion of South Sea blood, the islanders have constantly been in

contact with

white men. Between 1808 and 1856, three hundred and fifty vessels

touched at

Pitcairn, and on various occasions shipwrecked mariners and others have

taken

up their abode on the island, and intermixed with the population. The

Pitcairn Islanders have been described as the "Beggars of the

Pacific," and, on the contrary, have also been depicted as saints in a

modern Eden. Needless to say they are neither the one nor the other,

but

inheritors of some of the weaknesses and a surprising amount of the

strength of

their mixed ancestry. From the

point of view of its main and scientific object, our visit had

satisfactory

results. The island was uninhabited when the mutineers arrived, but

there were

traces of past residents. The sites of three "maræ,”

or native structures, among the undergrowth

were pointed out. They are said to have been preserved by the first

Englishmen,

but were unfortunately destroyed comparatively recently and very little

of them

is still preserved. The old people could remember when bones could be

seen

lying about in their vicinity. The islanders most kindly offered to dig

out

what still existed of these remains, and two days running the whole

population

turned out for excavation. The most interesting of the erections proved

to be

one situated on the cliff looking down on to Bounty Bay; we were only

able

roughly to examine it on the morning of our departure. It appeared to

have been

made of earth, not built of stone, and by clearing away some of the

scrub we

were able to arrive at the conclusion that it had been an embankment

some 12

feet high, built on the immediate edge of the vertical cliff, and had

had two

faces. The face that was directed seawards was almost vertical, whilst

the one

towards the land formed an inclined plane, that measured 37 feet

between its

highest and its lowest points. It seemed clear that both sides had been

paved

with marine boulders. In general character it resembled to some extent

one of

the semi-pyramid ahu of Easter, but dense vegetation and tree growth

rendered

it impossible to speak definitely, and the form may have been

determined by the

shape of the cliff. It was remembered that three statues had stood on

it. and

that one in particular had been thrown down on to the beach beneath.

The

headless trunk of this image is preserved; it is 31 inches in height,

and the

form has a certain resemblance to that of Easter Island, but the

workmanship is

much cruder. There is said to have been also a statue on a maræ on the

other

side of the island. There are

interesting rock carvings in two places, both of which are somewhat

difficult

to reach. S. managed however to photograph one set, and a dear old man

undertook

the scramble to the other site, which was practically inaccessible to

booted

feet, and made drawings of them for the Expedition. Then we

had a great whip-up for any stone implements which might have been

found; Miss

Beatrice Young most kindly assisted and induced the owners to bring out

their

possessions. Over eighty were produced. The Islanders were much pleased

to

think that their contribution would be numbered among the treasures of

the

British Museum, but the argument that "a hundred years hence they would

still be there" left them cold; for, as they explained, “the end of the

world would have come before then." We spent

in all four nights on the island, which forms, we believe, a record

sojourn for

visitors; it is a very happy memory. A large portion of the population

asked

for passages to Tahiti, but the hearts of most failed before the end,

and we on

our part drew the line at taking more than two men, who would work

their

passage. Those who finally came with us were brothers, Charles and

Edwin Young,

descendants of Midshipman Young. They arrived on board with their hats

wreathed

with flowers — true Polynesian fashion — accompanied by many friends

and

relatives. Charles had been on one of the island trading vessels, but

Edwin had

never before left his home (fig. 132). From

Pitcairn we made for Rapa, known as Rapa-iti or Little Rapa, to

distinguish it

from Rapa-nui or Great Rapa; which, as has been seen, is one of the

names for

Easter. It is a French possession and only visited by a vessel

occasionally. It

is seven hundred miles from Pitcairn, and was somewhat out of our route

for

Tahiti, but the Sailing Directions reported a number of prehistoric

buildings,

which they termed "forts." We were anxious to inspect them and see

what relation, if any, they bore to buildings on Easter Island; but

disappointment, alas! awaited us. The side

of the island on which is the settlement was at the time of our visit

the

windward aspect; there was a strong breeze and quite a heavy sea. We

remained

abreast the village for some hours awaiting the pilot, who is said to

come off

to visiting vessels, but no one appeared, nor was any signal made on

the shore.

Either they were afraid of us, or did not like the look of the weather.

It was

not one of the islands we had originally intended visiting, and we had

no

chart. We had to

sail the ship the whole time in order to keep our station, and

eventually our

forestay gave out; this meant putting her instantly before the wind, or

we

should have been dismasted. We therefore ran under the lee of the land

and made

good our damage. It would have taken a long time to thrash back to our

original

station, so we reluctantly gave up the attempt to make a landing. The

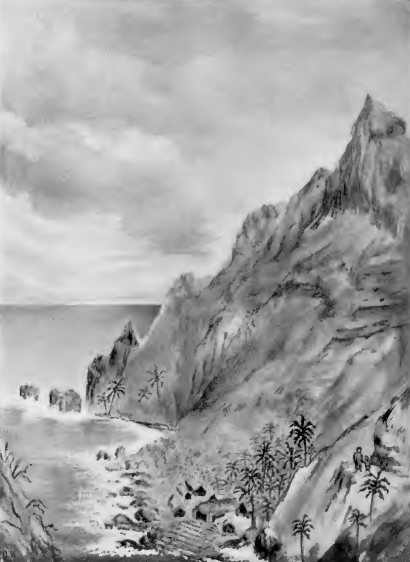

coast is

extremely fine, bold, and precipitous, but that, and the illustration

given, is

all that we can tell of Rapa.  FIG. 129. — THE ISLAND OF RAPA. 1 They

had, of course, no connection with Adams the mutineer. |