| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

XV

NATIVE CULTURE IN PRE-CHRISTIAN TIMES Sources of Information: History, Recent Remains, Living Memory — Mode of Life: Habitations, Food, Dress and Ornament — Social Life: Divisions, Wars, Marriages, Burial Customs, Social Functions. It has

been seen that any knowledge which exists on the island with regard to

the

origin of the monuments is of the most vague description, and it is

therefore

necessary, in the attempt to solve the problem, to rely principally on

indirect

evidence. It becomes in particular essential to collect all possible

information about the present people; not only for its intrinsic

anthropological

interest, but in order to find if any links connect them with the great

builders, or if we must look for an earlier race. As a

first step in the search the scientist naturally turns to the most

ancient

accounts which he can find describing the island, its inhabitants, and

remains;

these are not yet two hundred years old. The first European to see it

was a

Dutch Admiral named Roggeveen, who came upon it on Easter Day, 1722,

during his

search for another and mysterious island known as Davis or David's

Island.1

He concluded that it was not the place for which he was looking,

christened it

Easter Island, and went further afield. His ship lay off the north side

of the

island for a week, but only on one day did landing take place, and one

or two

of the party have left us short descriptions. There were, they say, no

big

trees, but it had a rich soil and good climate; there were sugar-cane,

bananas,

potatoes and figs, and the natives brought them a number of fowls,

estimated

varyingly from sixty to five hundred. One of the voyagers goes so far

as to say

that "all the country was under cultivation." As for the inhabitants,

they were, they tell us, of all shades of colour, yellow, white, and

brown, and

wore clothes made of a "field product," evidently tapa. They were

"painted," which apparently signifies tattooed, and it was the habit

to distend the lobes of their ears so that they hung to the shoulders,

and

large discs were worn in them. “When these Indians," wrote Roggeveen,

"go about any job which might set their ear-plugs wagging, and bid fair

to

do them any hurt, they take them out and hitch the rim of the lobe up

over the

top of the ear, which gives them a quaint and laughable appearance." 2

The

natives were extraordinarily thievish, stealing the caps from the

seamen's

heads, while one actually climbed into the port-hole of the cabin and

took the

cloth off the table. These habits gave rise to an unfortunate incident,

as when

the visitors came on shore, a scuffle took place over the sanctity of

property,

and the natives began throwing stones, on which a petty official gave

the order

to fire, ten or twelve natives being killed. The occurrence, however,

was duly

explained, and did not terminate amicable relations. We learn that at

this time

the great statues, of which this is of course the first report, were

then, as

has already been noted, standing and in place. The Dutchmen describe

them as

"remarkable, tall, stone figures, a good 30 feet in height," and

notice that they have crowns on their heads; a clear space was, they

said,

reserved round them by laying stones. They have no doubt that the

figures are

objects of worship; the natives "kindle fires in front of them, and

thereafter squatting on their heels with heads bowed down, they bring

the palms

of their hands together and alternately raise and lower them." Another

observer adds, in connection with this worship, that they "prostrated

themselves towards the rising sun." A great step would have been gained

towards the solution of the problem if we could feel assured that these

last

remarks were justified and were not merely the result of imperfect

observation. 3 For fifty

years darkness once more descends on the history of the island. Then,

within a

period of sixteen years, it was visited by three expeditions, Spanish,

English,

and French respectively. The Spanish were under the command of Gonzalez.4

They too were searching for David's Island when, in 1770, they touched

at

Easter, and they also came to the conclusion that it was not their

goal. They

took, however, formal possession of it, and named it San Carlos. Their

ships

lay at anchor in the same place as had those of Roggeveen, the bay on

the north

coast now called after La Pérouse. From this anchorage three curious

hillocks

on the northern slope of the great eastern volcano form striking

objects (fig.

78); on each of these they planted a cross, and proclaimed the King of

Spain

with banners flying, beating of drums, and artillery salutes. The

natives

appear to have thoroughly enjoyed the proceedings, and "confirmed

them," according to the solemn statements of the Spaniards, by marking

the

official document with their own script. This is the first that we hear

of a

form of native writing. The expedition sent a boat round the island,

which made

a very creditable map of it. Four

years later Cook cast anchor on the west side in the bay which is known

by his

name. He was there three days and did not himself explore inland, but

his

officers did so, including the elder Forster, the botanist of the

expedition,

and his account of what they saw was published by his son.5 In 1780

La Pérouse anchored in the same place, and also sent some of his men

inland,

who covered partly, but not entirely, the same districts as those of

Cook.6 As these

expeditions were so nearly of the same date, their remarks may fairly

be

compared and contrasted with those made by Roggeveen half a century

earlier.

All three give very similar descriptions of the people, their

appearance and

dwellings, which also resemble the accounts of the Dutch. Cook is very

much

impressed with the long ears, though La Pérouse does not refer to them.

There

is the same story of the native powers of appropriating the goods of

the strangers.

Cook says that they were "as expert thieves as any we had yet met

with," and Pérouse, whose own hat they stole while helping him down one

of

the image platforms, is particularly aggrieved at such conduct,

considering

that he has given them sheep, goats, pigs, and other valuable presents;

peace

was only kept between the crew and the natives by official compensation

being

given the seamen for their lost property. Here,

however, the resemblance of these accounts with that of Roggeveen ends.

The

descriptions which are given by these later expeditions of the state of

the

country, and its facilities as a port of call, are very different from

those of

the Dutchmen. The Spaniards speak of it as being uncultivated save for

some

small plots of ground. The Englishmen are the reverse of enthusiastic.

Forster

calls it a "poor land," and Cook says that "no nation need

contend for the honour of the discovery of this island, as there can be

few

places which afford less convenience for shipping." "Poultry"

now consists of only a "few tame fowls" — later still we find that

only one is produced. Pérouse, although he is not so depressed as Cook,

tells

us that only one-tenth of the land is cultivated. With regard to the

population

Roggeveen gives no number, and probably was not in a position to do so.

The

estimates made by the Spanish and English are very similar. Gonzalez

puts it at

nine hundred to one thousand, Cook at seven hundred; both of them,

however,

state that the number of women seen seemed to be disproportionately

small. La Pérouse,

writing of course some years later, speaks of the number as two

thousand and

has seen many women and children. Both English and French are

interested to

find that the language is similar to that spoken elsewhere in the

Pacific. Again, in

dealing with the state of the monuments and the way in which they were

regarded, the impressions of the later observers differ greatly from

those of

Roggeveen. The Spaniards do not tell us very much. They saw from the

sea what

they thought were bushes symmetrically put up on the beach, and dotted

about

inland; later they found that they were in reality statues, and they

wondered

particularly how their crowns, which they observed were of a different

material, were raised into place. It was one of the Spanish officers

who

states, as recorded at the beginning of this book, that the seashore

was lined

with stone idols,7 from which it may be gathered

that the great

majority were still erect. The figures were, they tell us, all set up

on small

stones, and burying-places were in front. It is interesting, in view of

what we

know of the prohibition of smoke near the ahu,8

to find one of the

Spanish writing: "They could not bear us to smoke cigars; they begged

our

sailors to extinguish them, and they did so. I asked one of them the

reason,

and he made signs that the smoke went upwards; but I do not know what

this

meant."9 Cook's people observed that the natives

disliked these

burying-places being walked over, but whereas Roggeveen was convinced,

whether

rightly or wrongly, that the cult of the statues was what we should

call "a

going concern," Cook, fifty years later, is equally certain that it is

a

thing of the past; some of the figures are still standing, but some are

fallen

down, and the inhabitants "do not even trouble to repair the

foundations

of those which are going to decay." "The giant statues," he says,

“are not in my opinion looked upon as idols by the present inhabitants,

whatever they may have been in the days of the Dutch." Forster also

remarks that "they are so disproportionate to the strength of the

nation,

it is most reasonable to look upon them as the remains of better

times."

La Pérouse does not agree with this last sentiment; he admits that at

present

the monuments are not respected, but he sees no reason why they should

not

still be made even under existing conditions; he thinks that a hundred

people

would be sufficient to put one of the statues in place. The objection

he sees

is that the people have no chief great enough to secure such a

memorial. It is

unfortunate that the mountain of Rano Raraku is so far removed from

both the north

and west anchorages, that none of the voyagers discovered it, although

Cook's

men were very near that from which the crowns were obtained.  [Drawn from Nature by W . Hodges.] FIG. 82. — MONUMENTS IN EASTER ISLAND. From A Voyage To-d'ards the South Pole, James Cook, 1777, vol. i., part of pi. xlix. The

artist has not observed the features or arms of the images, nor that

they stand

on stone platforms. The hats, as shown, greatly exceed their true

proportion to

the figures. The picture has probably been redrawn from memory. In the

nineteenth century we have a few accounts from passing voyagers.

Lisiansky, in

1804, found no people with long ears,10 but in

1825 Beechey in

H.M.S. Blossom says that there were

still a few to be seen. With regard to the statues, the process of

demolition

has gone so far that Beechey declares "the existence of any busts is

doubtful."11 It

is

amusing to find, a hundred years after Roggeveen's similar experience,

that the

Blossom has an affray with natives over the stealing of caps. While

attention

has been drawn to the importance of these early narratives, it must be

remembered that all the visits were of very short duration, and that

the old

voyagers were not trained observers. The Dutchmen, for instance,

deliberately

tell us that the statues have no arms. The accounts frequently give the

impression of being written up afterwards from somewhat vague

recollection, and

in most cases the narrators have read those of their predecessors and

go

prepared to see certain things. One navigator who never landed assures

us that

the houses are the same as in the days of La Pe rouse. On the other

hand, with

regard to the stores available, they are, so to speak, on their own

quarter-deck, and their remarks can be accepted without question. In the

"sixties" of last century the great series of changes took place

which brought Easter Island into touch with the modern world. The first

of

these largely broke those chains with the past which the archaeologist

now

seeks to reconstruct. Labour was needed by the exploiters of the

Peruvian guano

fields, and an attempt which was made to introduce it from China having

failed,

slave-raids were organised in the South Sea Islands. As early as 1805

Easter

had suffered similarly at the hands of American sealers, and it was

amongst the

principal islands to be laid under contribution in December 1862. It is

pathetic even now to hear the old men describe the scenes which they

witnessed

in their youth, illustrating by action how the raiders threw down on

the ground

gifts which they thought likely to attract the inhabitants, and, when

the

islanders were on their knees scrambling for them, tied their hands

behind

their backs and carried them off to the waiting ship. The natives say

that one

thousand in all were so removed from the island, and, unfortunately,

there were

amongst them some of the principal men, including many of the most

learned, and

the last of the ariki, or chiefs. Representations were made by the

French

Minister at Lima, and a certain number were put on board ship to be

returned to

their home. Smallpox, however, had been contracted by them, and out of

one

hundred who were to be repatriated, only fifteen survived. These, on

their

return to the island, brought the disease with them, which spread

rapidly with

most fatal results to the population. Meantime,

shortly before the raid, the attention of the Roman Catholic

"Congregation

of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and Mary” in Valparaiso had been drawn to

the

island by the account received from a passing ship, and they determined

to

inaugurate a mission. Three of the Community left for Easter Island,

their

route taking them by way of Tahiti. Finally, only one continued, Eugene

Eyraud,

who landed on the island in January 1864. Eyraud was a lay brother in

the Order,

having been a merchant in South America; he devoted his life to the

call to

take the Gospel to Easter, and the accounts of his work, which are

extraordinarily interesting, leave a great impression of his courage

and

devotion.12 He was alone on the island for eight

or nine months, and

was at the mercy of the natives, who stole his belongings, even to the

clothes

he was wearing, and compelled him to make a boat for them. In March

1866,

Eyraud, after a visit to Chile, returned with another missionary,

Father Roussel,

and the two were for a while blockaded in a house which they had put

up, but

the tide now turned. Either Roussel was a man of greater determination

than

Eyraud, or with increased numbers a firmer attitude was possible.

Surgeon

Palmer of H.M.S. Topaze tells us

that

when one of the natives took up a stone with a menacing gesture,

Roussel

quietly felled him with his stick and went on his way, after which

there was no

further trouble. The missionaries were joined later in the year by two

more of

their number, and became a power in the land. Eyraud on

his return from Chile was suffering from phthisis, of which he died in

August

1868. When he was nearing his end he asked Roussel if there still

remained any

heathen in the island, to which the Father replied "not one"; the

last seven had been baptized on the Feast of the Assumption. It seems

natural

to connect with Eyraud 's illness the fact that there was at the same

time a

severe epidemic of phthisis in the island; so little was the need of

precaution

understood at this date, that even Surgeon Palmer, writing of the

inroads made

by consumption, remarks "which they (the natives) believe

infectious."13 The

ravages of this disease, following on those of smallpox, reduced the

population, which at the time of the arrival of the mission had stood

at twelve

hundred, by about one-fourth. The

remarks of the missionaries on native customs, particularly those

dealing with

their ceremonies, reflect credit on the observers at a time when such

things

were too often thought beneath notice; they will be referred to later.

Their

ethnological work was, however, limited by more pressing exigencies, by

the

difficulties of locomotion on the island, and by the language. Roussel

compiled

a vocabulary, which is useful to students, though not free from the

mode of

thought found in a well-known missionary dictionary, which translates

hansom

cab into the Swahili language. It is a curious fact that so completely

were the

terraces now ruined that the Fathers never allude to the statues, and

seem

scarcely to have realised their existence; but it is through them that

we first

hear of the wooden tablets carved with figures. The body of professors

acquainted with this art of writing perished, either in Peru or by

epidemic,

and this, in connection with the introduction of Christianity, led to

great

destruction of the existing specimens of this most interesting script.

The

natives said that they burnt the tablets in compliance with the orders

of the

missionaries, though such suggestion would hardly be needed in a

country where

wood is scarce; the Fathers, on the contrary, state that it was due to

them

that any were preserved. Some certainly were saved by their means and

through

the interest shown in them by Bishop Jaussen of Tahiti, while two or

three

found their way to museums after the natives became aware of their

value; but

some or all of these existing tablets are merely fragments of the

original. The

natives told us that an expert living on the south coast, whose house

had been

full of such glyphs, abandoned them at the call of the missionaries, on

which a

man named Niari, being of a practical mind, got hold of the discarded

tablets

and made a boat of them wherein he caught much fish. When the "sewing

came

out," he stowed the wood into a cave at an ahu near Hanga Roa, to be

made

later into a new vessel there. Pakarati, an islander now living, found

a piece,

and it was acquired by the U.S.A. ship Mohican. Side by

side with the establishment of the religious power the secular had come

into being.

The master of the ship who had brought the last two missionaries was a

certain

Captain Dutrou Bornier. He had been attracted by the place; and, having

made

financial arrangements with the mercantile house of Brander in Tahiti,

settled

himself on the island and proceeded to exploit it commercially.

Title-deeds

were obtained from the natives in exchange for gifts of woven material.

The

remaining population was gathered together into one settlement at Hanga

Roa,

the native name for the shore of Cook's Bay. This was the state of

things when

H.M.S. Topaze touched in 1868 and

carried off the two statues now at the British Museum. Dutrou

Bornier had at first spoken enthusiastically of the work of the

missionaries;

later, however, the not unknown struggle arose between the religious

and

secular powers. According to the accounts of the missionaries, they

protested

against the actions of Bornier in taking over two hundred natives,

practically

by force, and shipping them to Tahiti to work on the Brander

plantations.

Bornier retaliated by rendering their position impossible, and the

Fathers

ultimately received orders to transfer their labours to the Gambler

islands.

Jaussen tells us that their converts desired to accompany them, and

that almost

the whole population went on board with them. The captain, however,

instigated

by Bornier, refused to carry so many, and one hundred and seventy-five

were

sent back to the shore. This, therefore, “was the whole population" in

1871.

We have not Bornier's account of the quarrel, but there seems to have

been some

justification for the attitude of the missionaries towards him, as five

years

later he was murdered by the natives, and, if current stories are to be

believed, his end was well merited. Subsequently

one of the Branders lived at Mataveri, and Mr. Alexander Salmon, to

whom the

missionaries sold their interests, at Vaihu on the south coast.14

The Salmon family had intermarried with the royal family of Tahiti, and

the new

resident was well aware of the value of antiquities. According to

native

accounts he organised a band to search the caves and hiding-places for

articles

of interest. They also state that he employed skilled natives to

produce wooden

objects connected with their older culture for sale to passing ships.

He spoke

the language of the island, and when the U.S.S. Mohican

arrived in 1886, he was the source of much of the

information which they subsequently published. It is an important but

difficult

matter to know how far the material thus gleaned thirty years ago was

carefully

obtained and reproduced. One or two of the folk-tales are still told

very much

as retailed by Salmon, but he appears to have taken little interest in

the

surviving customs and failed to understand them. The report of the Mohican, made by Paymaster Thomson, has

been the only account of the island in existence with any pretention to

scientific value.15 The Mohican

was there eleven days, and Thomson went rapidly round the island with a

party

from the ship. The amount of ground covered and work done is

remarkable,

although his statements are naturally not free from the errors

inseparable from

such rapid observation. In 1888

the Chilean Government formally took possession. In 1897 M. Merlet, of

Valparaiso, purchased from the representatives of Brander, Bornier, and

Salmon,

their interest in Easter Island, with the exception of a tract of land

containing the village of Hanga Roa, which the Chilean Government

acquired from

the missionaries and retained in the interest of the inhabitants; this

land covers

a far larger space than the natives are able to utilise. The population

is

again increasing, as will have been seen from the fact that during our

visit

they numbered two hundred and fifty. M. Merlet subsequently sold his

holding to

a company, of which he became chairman. Easter

Island has had many names. That given by the Dutchman has become

generally

accepted, but the Spaniards christened it San Carlos, and in some maps

it is

termed "Waihu," a name of a part of the island erroneously understood

as applying to the whole. A native name is Te Pito-te-henua, "henua" means usually

"earth" and "pito"

"navel."16 Thomson says it was ascribed to the

first

comers. Elsewhere in the Pacific "pito" also means "end."

Churchill holds the name signified simply "Land's End," and was

applied to all these angles of the island, which was itself without a

name.17

Rapa-nui (or Great Rapa) is another native name for which various

explanations

are offered. The

island of Rapa, sometimes known as Rapa-iti, lies some two thousand

miles to

the westward. Thomson states that the name Rapa-nui only dates from the

time

when the men kidnapped by the Peruvians were being returned to their

homes. The

Easter Islanders, finding no one knew the name Te Pito-te-henua, and

that some

comrades in distress from the other Rapa managed to make their place of

origin

understood, called their own home Rapa-nui; a story which sounds hardly

probable, but was presumably obtained from Salmon. According

to the report of H.M.S. Topaze, the

Islanders of their day believed that Rapa was their original home.

Others state

the name was given by a visitor from that island. The brief

accounts which have been referred to are all that is known from

external

evidence of the original life of the present people, and but little

hope was

held out to us in England that those fragments could still be

supplemented.

There were found, however, to be still in existence two possible

sources of

information, namely, the memories of old inhabitants, and the actual

traces

which still remain of the life led by the people previous to the

Peruvian raid

and the coming of Christianity. The great ahu which have so far been

described

are only a part, although the most imposing portion, of the stone

remains of

the island. It is fortunate for the student that when civilisation

appeared the

natives were gathered into one settlement, for they left behind them,

sprinkled

over the island, various erections connected with their original

domestic life.

These buildings were certainly being used in recent times, and are

treated from

this point of view, but for all we know they may have been, and very

possibly

were, contemporary with the great works. The study

of the remains on the island, from the greatest to the least, is by no

means so

simple as may hitherto have appeared. Our earliest attempts at

descriptions,

although conscientious, were almost ludicrous in the light of

subsequent

knowledge, and Captain Beechey's error on the subject of "the busts"

is at least comprehensible. Easter, it must be remembered, is a mass of

disintegrating rocks. When in an idle moment the Expedition amused

itself by

inventing an heraldic design for the island, it was universally agreed

that the

main emblem must undoubtedly be a "stone," "and as

supporters," suggested one frivolous member, “two cockroaches

rampant." The most correct representation would be a stone vertical on

a

stone horizontal. Every individual who has lived, even temporarily, in

the

place, has collected stones and put them up according to taste; and

every

succeeding generation, also needing stones, has, as in the instance of

the manager's

wall, found them most readily in ruining or converting the work of

their

predecessors. Even when a building is comparatively intact, the

original design

and purpose can only be grasped by experience, and matters become

distinctly

complicated when the walls of an ahu have been made into a garden

enclosure and

a chicken-house turned into an ossuary. It must be remembered also that

rough

stone buildings bear in themselves no marks of age. The cairns put up

by us to

mark the distances for rifle fire from the camp were indistinguishable

from

those of prehistoric nature made for a very different purpose. The

result is

that the tumble-down remains of yesterday, and the scenes of unknown

antiquity

blend together in a confusing whole in which it is not always easy to

distinguish even the works of nature from those of man. The other

source of information which was open to us was the memory of the old

people. If

but little was known of the great works, it was possible that there

might still

linger knowledge of customs or folk-lore which would throw indirect

light on

origins. This field proved to be astonishingly large, but it was even

more

difficult to collect facts from brains than out of stones. On our

arrival there

were still a few old people who were sufficiently grown up in the

sixties to

recall something of the old life; with the great majority of these,

about a

dozen in number, we gradually got in touch, beginning with those who

worked for

Mr. Edmunds and hearing from them of others. It was momentous work, for

the

eleventh hour was striking, day by day they were dropping off; it was a

matter

of anxious consideration whose testimony should first be recorded for

fear

that, meanwhile, others should be gathered to their fathers, and their

store of

knowledge lost for ever. Against the longer recollection of extreme old

age,

had to be put the fact that the memories of those a little younger were

generally more clear and accurate. The feeling of responsibility from a

scientific point of view was very great . Ten years ago more could have

been

done; ten years hence little or nothing will remain of this source of

knowledge. Most

happily, these authorities were in almost every case willing and ready

to talk,

and our debt to them is great. They came with us, as has been seen, on

our

explorations of the island, but the greater part of the work was done

when we

were living near the village. Some of them took pleasure in coming up

to

Mataveri and talking in the veranda, enjoying still more, no doubt, the

practical outcome of their subsequent visits to Bailey's domain — the

kitchen.

Others were more at ease in their own surroundings, and then we went

down to

the village and discussed old days in their little banana-plots, while

interested neighbours came in to join the fray. Sometimes a man did

better by

himself, but on other occasions to get two or three together stimulated

conversation. Unfortunately, some of the old men who knew most were

confined to

the leper settlement some three miles north of Hanga Roa, and the

infectious

power of leprosy was not a subject which we had got up before leaving

England.

The Captain of the Kildalton feared

lest even the distance of the settlement from the manager's house might

not

suffice to prevent the plague being carried there by insects, and told

a

gruesome tale, within his knowledge, of two white men who had gone for

a visit

to a Pacific island, one of whom on their return to an American port

had been

immediately sent back to a leper colony. But how could one allow the

last

vestige of knowledge in Easter Island to die out without an effort? So

I went,

disinfected my clothes on return, studied, must it be confessed, my

fingers and

toes, and hoped for the best. It would

not be easy for a foreigner to reconstruct English society fifty years

ago,

even from the descriptions of well-educated old men: it is particularly

difficult to arrive at the truth from the untutored mind. Even when the

natives

knew well what they were talking about, they would forget to mention

some part

of the story, which to them was self-evident, but at which the humble

European

could not be expected to guess. The bird story, for example, had for

many

months been wrestled with before it transpired precisely what was meant

by the

"first egg." Deliberate invention was rare, but, when memory was a

little vague, there was a constant tendency to glide from what was

remembered

to what was imagined. Scientific work of this nature really ought to

qualify

for a high position at the bar. The witness had to be heard, and

discreetly

cross-examined without any doubt being thrown on his story, which would

at once

have given offence; then allowed to forget and again re-examined, his

story

being compared with that of others who had been heard meanwhile.

Counsel had

also to be judge and to act as reporter, and at the same time keep the

witness

amused and prevent the interpreter from being bored, or the court would

promptly have broken up. Though great care has been exercised, it must

be

remembered, when a particular account is quoted, as, for example, that

of Te

Haha regarding the annual inspection of the tablets, while it is

believed to

rest on fact, its absolute accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The

language question naturally added to the difficulty. On landing two

courses had

been open, either to go on with Spanish, of which the younger men had a

certain

knowledge, and which was used by Mr. Edmunds, or to try to get some

hold of the

native tongue. The latter plan was decided on, and though at one time

the

difficulties seemed so great that this course was almost regretted, in

the end

it was vindicated. There is, as stated, a vocabulary in French made by

the

missionaries, and also one in Spanish, but there is no grammar of any

kind.

The next

stage, the putting together of sentences, was still more difficult .

How was it

possible to talk in a language which had no verb "to be"? I had, it

is true, a native maid (fig. 29), but, after the simplest phrases had

been

learnt, topics for conversation were difficult to find. We looked

through

illustrated magazines together, but wild beasts, railway trains, and

the

greater part of the pictures of all kinds, conveyed nothing to her. The

plan

was therefore hit on of a tale, after the manner of the Arabian

Nights, dealing with imaginary events on the island; it was

very weird, but served its purpose, though there were initial

difficulties. The

heroine, for instance, was christened "Maria," but "there

were," Parapina said, "three Marias on the island. Which was it?” and

it was long before she grasped, if indeed she ever did so entirely,

that the

lady was imaginary. A certain sequence of events was somehow made

intelligible

to her. She was then induced to repeat the story, while it was taken

down. It

was copied out and next day read again to her for further correction.

Every

word and idea gained was a help in understanding local names and the

native

point of view. Before the end, in addition to using the language for

the

ordinary affairs of life, it was found possible to get simple answers

direct

from the old men, and understand first-hand much of what they said. Any real

success in intercourse was, however, due to the intelligence of one

individual

who was known as Juan Tepano. He was a younger man about forty years of

age, a

full-blooded Kanaka, but had served his time in the Chilean army, and

thus had

seen something of men and manners; he talked a little pidgin English,

which was

a help in the earlier stages, but before the end he and I were able to

understand each other entirely in Kanaka, and he made clear to the old

men

anything I wished to know, and explained their answers to me. It was

interesting to notice how his perception gradually grew of what truth

and accuracy

meant, and he finally assumed the attitude of watch-dog to prevent my

being

imposed on. Happily, it was discovered that he was able to draw, and he

took

great delight in this new-found power, which proved most useful. The

tattoo

designs were obtained, for example, by giving him a large sheet of

paper with

an outline of a man or woman, also a pencil and piece of candle; these

he took

down to the village, gathered the old men together in their huts in the

evening, and brought up in the morning the figure adorned by the

direction of

the ancients (fig. 88). He took a real interest in the work, learning

through

the conversations much about the place which was new to him, and at the

end of

the time triumphantly stated, “Mam-ma now knows everything there is to

know

about the island." It is

proposed to unite the information gained from locality and memory,

referring

where necessary to the accounts of the early voyagers, and give as

complete

descriptions as possible of the primitive existence which continued on

Easter

Island till the middle of last century. It will be seen that the

condition of

the people on the coming of Christianity, as we were able to ascertain

it,

corresponded almost exactly with that described by the first visitors

from

Europe, more than a hundred years earlier. Such traditions as linger

regarding

the megalithic remains have already been alluded to earlier in this

book, but

attention will be drawn to the point whenever this line of research

seems

successful in throwing indirect light on the origin of the great works.

Mode

of Life.

— The

present natives, in talking of old times, say that their ancestors were

"as thick as grass," and stood up like the fingers of two hands with

the palms together; a statement from which deduction must be made for

pictorial

representation. The early mariners never, as we have seen, estimate the

population at more than two thousand, but the land could carry many

more. Mr.

Edmunds calculates that about half of the total amount (or some 15,000

acres)

could grow bananas and sweet potatoes. Two acres of cultivated ground

would be

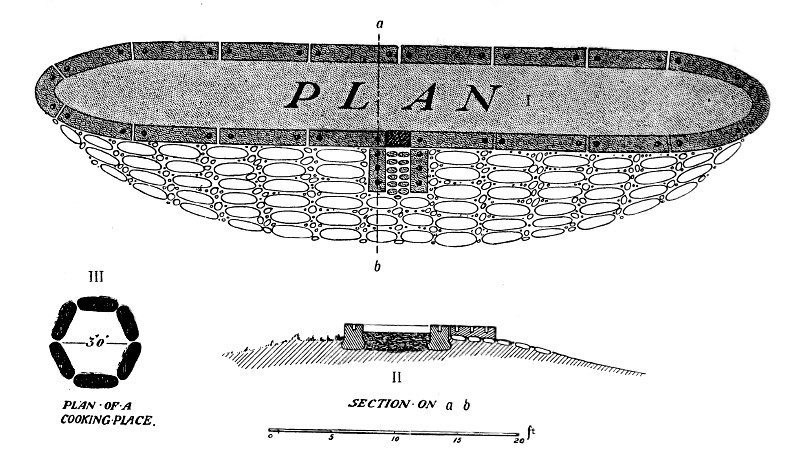

sufficient to supply an ordinary family.  FIG. 84. — STONE FOUNDATIONS.  FIG. 84A. —ENTRANCE AND PAVED AREA. Housing

accommodation presented no great problem. Many slept in the open, and

even

to-day, in the era of Christianity and European clothes, a cave is

looked upon

as sufficient shelter. When on moving from our "town" to our

"country" house we inquired where our attendants were to sleep, we

were cheerfully informed "it was all right, there was a very good cave

near Tongariki" — and this cave, called Ana Havea, became a permanent

annexe to the establishment (fig. 124). Some of these caves had a wall

built in

front for shelter. Houses,

however, did exist, which were built in the form of a long upturned

canoe; they

were made of sticks, the tops of which were tied together, the whole

being

thatched successively with reeds, grass, and sugar-cane. In the best of

these

houses, the foundations, which are equivalent to the gunwale of the

boat, are

made of wrought stones let into the ground; they resemble the

curbstones of a

street pavement save that the length is greater. In the top of the

stones were

holes from which sprang the curved rods, which were equivalent to the

ribs of a

boat, and formed the walls and roof (figs. 84 and 85) . The end stones

of the

house are carefully worked on the curve, and it is very rare to find

them still

in place, as they were comparatively light, weighing from one to two

hundredweight, and easily carried off. Even the heavier stones were at

times

seized upon as booty in enemy raids; one measuring 15 feet was pointed

out to

us near an ahu on the south coast, which had been brought all the way

from the

north side of the island. In the middle of one side of the house was a

doorway,

and in the front of it a porch, which had also stone foundations. The

whole

space in front of the house was neatly paved with water-worn boulders,

in the

same manner as the ahu. This served as a stoop on which to sit and

talk, but

its practical utility was obvious to ourselves in the rainy seasons,

when the

entrance to our tents and houses became deep in mud (fig. 84A). Near

the main

abode was a thatched house which contained the native oven, the stones

of which

are often still in place. The cooking was done Polynesian fashion: a

hole about

15 inches deep is lined with fiat stones, a fire is made within, and,

when the

stones are sufficiently heated, the food, wrapped up in parcels, is

stacked

within and covered with earth, a fire being lighted on the top. Many of

the surviving old people were born and brought up in these houses,

which are

known as "haré paenga." The old man, for example, before alluded to,

who was brought out to Raraku, roved round the mountain telling with

excitement

who occupied the different houses in the days of his youth. He gave a

particularly graphic description of the scene after sundown, when all

were

gathered within for the evening meal. In addition to the main door,

there was,

he said, an opening near each end by which the food was passed in and

then from

hand to hand; as perfect darkness reigned, a sharp watch had to be kept

that it

all reached its proper owners. He lay down within the old foundations

to show

how the inhabitants slept. This was parallel to the long axis of the

house, the

head being towards the door; the old people were in the centre in

couples, and

the younger ones in the ends. The largest of these houses, which had

some

unique features, measured 122 feet in length, with an extreme width of

12 feet;

but some 50 feet by 5 feet or 6 feet are more usual measurements. They

were

often shared by related families and held anything from ten to thirty,

or even

more, persons.  FIG. 85. — CANOE-SHAPED HOUSE. Diagram of stone foundations, paved area and cooking-place. The food

consisted of the usual tropical produce, such as potatoes, bananas,

sugar-cane,

and taro. Animal diet formed a very small part of it, rats being the

only form

of mammal; but chickens played an important role in native life, and

the

remains of the dwellings made for them are much more imposing than

those for

human beings. They are solid cairns, in the centre of which was a

chamber,

running the greater part of their length; it was entered from outside

by two or

more narrow tunnels, down which the chickens could pass. They were

placed here

at night for the sake of safety, as it was impossible to remove the

stones in

the dark without making a noise (fig. 86). Fish are not very plentiful,

as

there is no barrier reef, but they also were an article of diet, and

were

bartered by those on the coast for the vegetable products obtained by

those

further inland. Fish hooks made of stone were formerly used, and a

legend tells

of a man who had marvellous success because he used one made of human

bone. The

heroes of the tales are also spoken of as fishing with nets. There are

in

various places on the coast round towers, built of stone, which are

said to

have been look-out towers whence watchers on land communicated the

whereabouts of

the fish to those at sea; these contained a small chamber below which

was used

as a sleeping apartment (fig. 87). Turtles appear on the carvings on

the rock,

and are alluded to in legend, and turtle-shell ornaments were worn; but

the

water is too cold for them ever to have been common, and Anakena is

almost the

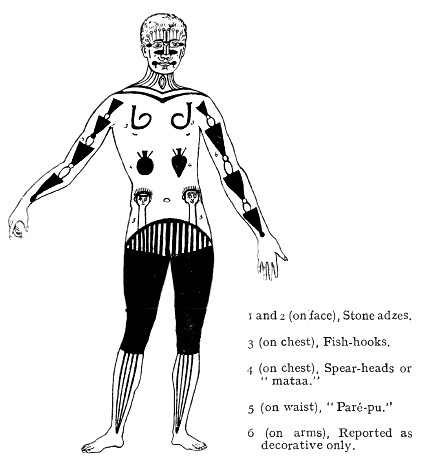

only sandy bay where they could have come on shore. The sole form of dress was the cloth made from the paper mulberry, and known throughout the South Seas as tapa; it was used for loin-cloths and wraps, which the Spaniards describe as fastening over one shoulder. Head-gear was a very important point, as witnessed by the way the islanders always stole the caps of the various European sailors. The natives had various forms of crowns made of feathers, some of them reserved for special occasions. Cherished feathers, particularly those of white cocks, were brought out of gourds, where they had been carefully kept, to manufacture specimens for the Expedition. The crowns are generally made to form a shade over the eyes, like the head-dresses of the images. Naturally, every effort was made to find the prototype of the image hats. No one recollected ever seeing anything precisely like it, but among the pictures drawn for us of various head-decorations was a cylindrical hat made of grass; the brim projected all the way round as with a European hat, but it had the same form of knot on the top as that of the statues.  FIG. 86. — HOUSE FOR. CHICKENS.  FIG. 87. — A TOWER USED BY FISHERMEN. Tattooing

was a universal practice, and the exactness of the designs excited the

admiration of the early voyagers, who wondered how savages managed to

achieve

such regularity and  FIG. 88. — DESIGNS USED IN TATTOOING, DRAWN BY NATIVES. accuracy.

The drawings made for us from the descriptions of the old people show

the men

covered, not only with geometrical designs, but with pictures of

every-day

objects, such as chisels and fish-hooks; even houses, boats, and

chickens were

represented in this way according to taste. The most striking objects

were

drawings of heads, one on each side of the body, known as "pare-pu,"

which the old mariners describe as "fearsome monstrosities"18

(fig. 88). Various old persons said that they remembered seeing men

with a

pattern on the back similar to the rings and girdle of the images. It

seems,

however, doubtful whether the image design merely represented tattoo,

in view

of the fact that it was raised, not incised, and in any case this would

only

put the search for its prototype a stage further back. The fact,

however,

remains that those particular marks were still being perpetuated, and

form a

link connecting the present with the past. Beechey, in 1825, tells us

the women

were so tattooed as to look as if they wore breeches. In addition to

this kind

of decoration, the islanders adorned themselves with various colours:

white and

red were obtained from mineral products found in certain places; yellow

from a

plant known as "pua,"19 and black from ashes of

sugar-cane. They had a distinct feeling for art. Some of the paintings

found in

caves and houses are obviously recent, and it is a frequent answer to

questions

as to the why and wherefore of things, that they were to make some

object

"look nice."

It will

be remembered that not only have the images long ears, but that all the

early

voyagers speak of them as general among the inhabitants. It was

therefore

somewhat surprising to find that no such thing was known as a man whose

ears

had been perforated, though with the women the custom went on till the

introduction of Christianity, and two or three females with the lobe

dilated in

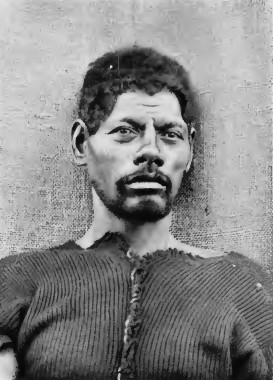

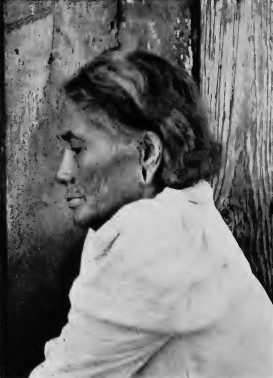

this manner still survived (fig. 90). At last one old leper recalled

that the

father of his foster-father had long ears, and on asking as a child for

the

reason, he had received the illuminating reply that "the old people had

them like that." He also mentioned one or two others with similar ears,

and this was subsequently confirmed by other authorities. It will be

seen that

the custom, as far as men were concerned, of dilating the lobe of the

ear, must

have been abandoned at the end of the eighteenth century, or just about

the

time of the visits of the Spanish, English, and French Expeditions.

That this

was cause and effect, and that they imitated the appearance of the

foreign

sailors, seems more than a guess; it will appear from other sources how

great

was the impression which was made by the foreigners. Social

Life.

—

Roggeveen's description of the people as being of all shades of colour

is still

accurate. They themselves are very conscious of the variations, and

when we

were collecting genealogies, they were quite ready to give the colour

of even

remote relations: "Great-aunt Susan," it would be unhesitatingly

stated, was "white," and "Great-aunt Jemima black." The

last real ariki, or chief, was said to be quite white. “White like me?”

I

innocently asked. “You!” they said, “you are red"; the colour in

European

cheeks, as opposed to the sallow white to which they are accustomed, is

to the

native our most distinguishing mark. It is obvious that we are dealing

with a

mixed race, but this only takes us part of the way, as the mixture may

have

taken place either before or after they reached the island. They were

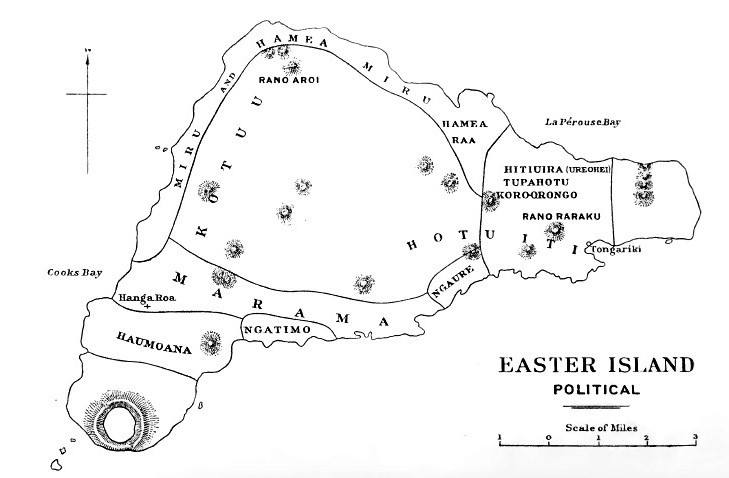

divided into ten groups, or clans ("máta"), which were associated

with different parts of the island, though the boundaries blend and

overlap;

members of one division settled not infrequently among those of

another. Each

person still knows his own clan. In

remembered times there were no group restrictions on marriage, which

took place

indiscriminately between members of the same or of different clans. The

only

prohibition had reference to consanguinity, and forbade all union

nearer than

the eighth degree or third cousins. These ten clans were again grouped,

more

especially in legend or speaking of the remote past, into two major

divisions

known as Kotuu (or Otuu), and Hotu Iti, which correspond roughly with

the

western and eastern parts of the island. These divisions were also

known

respectively as Mata-nui,

or greater clans, and Mata-iti, or lesser clans. The lower portions of

the

island were the most densely populated parts, especially those on the

coast,

and the settlements on the higher ground appear to have been few (fig.

91). In Kotuu,

the Marama and Haumoana inhabited side by side the land running from

sea to sea

between the high central ground and the western volcano Rano Kao. They

had a

small neighbour, the Ngatimo, to the south, and jointly with the Miru

spread

over Rano Kao and formed settlements by the margin of the crater lake.

The Miru

lived on the high, narrow strip between the mountain in the apex and

the cliff,

and mixed up with them was a lesser people, the Hamea. To the east was

another

small clan, the Raa, which is spoken of in conjunction with the Miru

and Hamea. The

principal Hotu Iti clans were the Tupahotu, the Koroorongo, and the

Hitiuira.

The last were generally known as the "Ureohei"; they inhabited

jointly the level piece of ground from the northern bay to the south

coast, and

had some dwellings on the eastern headland. Next to them on the south

coast was

a small group, the Ngaure.20 The particular

importance of the clans

lies in the fact that, while they may be merely groups of one body,

they may,

on the other hand, represent different races or waves of immigrants. If

there

have been two peoples on Easter Island, these divisions are one place

where we

must at least look for traces for it. Legend

tells of continual wars between Hotu Iti and Kotuu. In recent times

general

fighting seems to have been constant, and took place even between

members of

one clan. A wooden sword, or paoa, was used, but the chief weapon was

made from

obsidian, and took from it the name of "mataa." This volcanic glass

is found on the slope of Rano Kao, but the principal quarries are on

the

neighbouring hill of Orito. Tradition says its use was first discovered

by a

boy who stepped on it and cut his foot. The obsidian was knapped till

it had a

cutting edge, and also a tongue, which latter was fitted into a handle

or stick

(fig. 92). The various shapes assumed were dignified by names, fourteen

of

which were given, such as "tail of a fish," "backbone of a

rat," "leaf of a banana." It was very usual to pick up these

mataa, and hoards were occasionally found; in one instance fifty or

sixty were

discovered below a stone in a cave, and in another case the

hammer-stone was

found with them which had been used in the process of squeezing off the

flakes.

The weapon was used both as a spear and as a javelin. A site is pointed

out

near Anakena, where a man throwing down hill killed another at about

thirty-five yards. The art of making these mataa is, of course,

practically

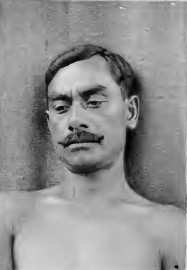

extinct, but one old man, commonly known as "He" (fig. 83), brought

us some which he had manufactured himself for the Expedition, and which

were

fairly well wrought. With the

exception of the Miru, of which more will be said, there were no chiefs

nor any

form of government; any man who was expert in war became a leader. The

warfare

consisted largely of spasmodic and isolated raids; an aggrieved person

gathered

together his neighbours and descended on the offenders. It is related

incidentally that one man, going along the south coast, “found war

going

on," one set of men having blocked up another in a cave. Another story

is

told of six men, called Gwaruti-mata-keva, of the clan Tupahotu, who

lived in a

cave in a certain hillock on the south coast, known as Toa-toa. They

went round

in a boat to Hanga Piko, stole fish, and returned rapidly to their

cave. A

hundred men from Hanga Piko then came overland to punish the robbery,

and made a

fire of grass before the cave in which the men lay hidden. When the

attackers

assumed that the enemy were all dead from suffocation, they went into

the cave;

but those within had buried their faces in holes scraped in the earth,

and when

the men from Hanga Piko entered, they arose and slew the whole hundred.

A more

interesting fact came out incidentally in connection with this gang of

Toa-toa,

connecting them with the secret societies found elsewhere in the

Pacific. They

were, it was said, in the habit of going about after dark with their

faces

painted red, white, and black, and visiting houses, where they declared

they

were gods, and demanded food, which the inhabitants accordingly gave

them. The

fraud, however, finally came to light when one day a man, who was

travelling

with his servant, saw them washing paint off their faces, “so they knew

that

they had deceived the people, and the people gathered together and

killed

them." In these

internecine fights fire was very generally set to the enemy's

dwellings. “He

often burnt houses," a young man said, pointing to an older one, and

the

impeachment was not denied. The ahu, too, were raided and bodies burnt,

which

seems to be the cause of the burnt bones recorded by certain

travellers; there

is no reason to suppose there was cremation or sacrifice on Easter

Island. It

was in this sort of warfare that the last images were overthrown.   [Brit. Mus.] FIG. 92. OBSIDIAN SPEAR-HEADS. (Mataa.) While

legends record how many people were eaten after each affray, all living

persons

deny, with rather striking unanimity, not only that they themselves

have ever

been cannibals, but that their fathers were so. If this is correct, the

custom

was dying out for some reason before the advent of Christianity;21

their

grandfathers, the old people admit, ate human flesh, but, if there were

any rites

connected with it, they "did not tell." The great-grandmother of an

old man of the Miru clan was, according to his account, killed on the

high

central part of the island by the Ureohei and eaten. In revenge for the

outrage, one of her sons, Hotu by name, killed sixty of the Ureohei.

Another

son, who had pacifist leanings, thought the feud ought then to be

ended, but

Hotu desired yet more victims, and there was a violent quarrel between

the two

brothers, in which the peace-maker was struck on the head with a club;

for, as

Hotu remarked, if they had slain his father, it would have been

different, but

really to eat his mother was "no good." Our

acquaintance with the person said to have been "the last cannibal,"

or rather with his remains, came about accidentally during the time

when I was

alone on the island. A little party of us had ridden to the top of the

volcano

Rano Kao; and on the southern side of the crater, that opposite Orongo,

some of

the natives were pointing out the legendary sites connected with the

death of

the first immigrant chief, Hotu-matua. Suddenly one of them vanished

into a

crevice in the rocks, and reappeared brandishing a thigh-bone to call

attention

to its large size. I dismounted, scrambled into a little grotto, or

natural

cave, where a skeleton was extended; the skull was missing, but the

jaw-bone

was present, and the rest of the bones were in regular order; the

individual

had either died there or been buried. Bones were in the department of

the

absent member of the Expedition, but it was of course essential to

collect

them, from the view of determining race, and the natives never resented

our

doing so. I therefore passed these out, packed them in grass in the

luncheon-basket,

and, sitting down on a rock, asked to be told the story of the cave.

“That,"

my attendants replied, “is Ko Tori." He was, they said, the last man on

the island who had eaten human flesh. In this hiding-place he had

enjoyed his

meals, and no one had ever been able to track him. There had formerly

been a

cooking-place, but it was now hidden by a fall of stones. He had died

as a very

old man at the other end of the island, apparently in the odour of

sanctity; to

judge by the toothless jaw if he had not deserted his sins they must

long ago

have deserted him. His last desire was to be buried in the place with

which he

had such pleasant connections, and in dutiful regard to his wishes, or

because

it was feared that his ghost might otherwise make itself unpleasant,

some of

the young men bore the corpse on stretchers along the south coast and

up to the

top of the mountain, depositing it here. The next thing was to get at

some sort

of date; chronology is naturally of a vague order, and the most

effective method

is, if possible, to connect events with the generation in which they

happened.

"Did your grandfather know him," was asked, "or your father?” The

answer was unexpected. “Porotu," they said, pointing to one of the old

men,

“helped to carry him," and silence fell on the group. My heart sank; I

had

then undone this last pious work and committed sacrilege. To my great

relief,

however, strange sounds soon made it clear that the humorous side had

appealed

to the escort; they were suffocating with mirth. "And now," they

said, gasping between sobs of laughter, “Ko Tori goes in a basket to

England." As I write, Ko Tori resides at the Royal College of Surgeons,

and has done his bit towards elucidating the mystery of Easter Island. Sexual

morality, as known to us, was not a strong point in life on the island,

but

marriage was distinctly recognised, and the absolute loose liver was a

person

apart. Polygamy was usual, but many seem to have had only one wife. The

children belonged to the father's clan, and are often distinguished by

his name

being given after their own. At the same time the clan of the mother

was not

ignored, and a man would sometimes fight for his maternal side. If a

man had

sons by more than one wife,, after his death each claimed the body of

his father

to lie on the ahu of his mother's clan, and the corpse might thus be

carried to

several in turn, finally returning to its own destination. We collected

a

certain number of genealogical trees, the various dramatis

personæ being for this purpose represented by matches or

buttons. It was not a very popular line of research, the cry being apt

to be

raised, “Now let's talk of something interesting"; but some two hundred

names were in this way placed in their family groups, with details of

clan,

place of residence and colour, and some knowledge obtained with regard

to many

more. It is not of course enough ground on which to found any theory,

but it

was very useful in checking information gathered in other ways. Only in

one

case was it possible to get back beyond the great-grandfather of our

informant,

but the knowledge of family connections was often greater than would be

found

among Europeans. The number of childless marriages was striking. The early

story of Viriamo (fig. 83), the oldest woman living in our day, gives a

picture

of this primitive state of things. She belonged to the clan of Ureohei,

and her

family had lived for some generations, as far back as could be

remembered, on

the edge of the eastern volcano, not far from Raraku. The

great-grandfather,

who was dark, had as his only wife a white woman of the Hamea. Their

son was

white, and had two wives, one of the Tupahotu and one of the Ngaure. By

the

first, although she also was white, he had a dark son who married a

white wife

of his own clan, Ureohei, but of a different group. Viriamo was the

second of

their eight children, all of whom were white save herself and her

eldest

brother. Four of the girls died young in the epidemic of smallpox in

1864.

Viriamo and two of her sisters were initiated as children into the bird

rite.22

When older she was tattooed with rings round her forehead and with the

dark-blue breeches. Somewhat later, but still as a young woman, she

went over

to Anakena and had her ears pierced, but she never had the lobe

extended, preferring

to let it remain small. When asked about her marriage, she bridled as

coyly as

a young girl. Her first union was a matter of arrangement, the husband,

who was

also of the Ureohei, giving her father much food, and, if she had

refused to

accept the situation, she would, she said, have been beaten. There was

no

ceremony of any kind, no new clothes nor feasting; her father simply

took her

to her new home and handed her over. The house was near the two statues

with

the projecting noses, excavated on the south-eastern slope of Raraku

(fig. 73),

and, when she wanted water, rather than cross the boundary and go round

to the

lake by the gap, through the hostile dwellers on the western side, she

used to

clamber with her vessel up the boundary rift in the cliff face. There

was one white

child, who died young, but her marriage was not a success, and Viriamo

left the

man and went off to live with one of the Miru clan at Anakena. His

house

already contained a wife and family, also four brothers, but they all

got on quite

happily together. She had five children by this man, who, like their

father,

were all white; four of them, however, died in infancy. This was the

result of

the parents having most unfortunately fallen foul of an old man, whose

cloak

had been taken without his consent, and who had accordingly prophesied

disaster. The remaining child, a daughter, was living and unmarried

when we

were on the island. The last husband was the most satisfactory of the

three; he

was a Tupahotu living near Tongariki. She was handed over to him as a

matter of

family arrangement, in discharge of a debt, but she was quite amenable

to the

exchange, and was very fond of him. He was light in colour, but her

only child

by this marriage, our friend Juan, was dark, taking, as he said, “after

my

mam-ma." The women

do not seem, judging by existing remains, to have had always a happy

time. Dr.

Keith, who examined the skulls collected by the Expedition, concludes

his

report on one of the female specimens as follows: "The most likely

explanation

is that the indent of the left temple was the cause of death, produced

by the

blow of a club, and that the suppuration and repair of the right side

has been

also produced by a former blow which failed to prove fatal. Two other

skulls,

also those of women, show indented fractures in the left temporal

region." Any

deficiency at marriages, in the way of social festivity, was made up at

funerals. These were attended by persons from all over the island, for

"when

they were not fighting, they were all cousins." In answer to the remark

that "considering the population their whole time must have gone in

this

way," it was cheerfully observed that "they had nothing else to do,

so they all went, everybody took food and everybody ate." The parents

of

one of our friends, Kapiera, lived at Anakena, but he was born on the

south side

of the island near Vaihu "when his mother went for a funeral." The

men who knew the tablets went also and sang, but there seems to have

been

little or nothing in the way of rites. The missionaries were impressed

with the

fact that there was no ceremony of any kind at a burial. Most

elaborate spells were, however, performed in connection with a man who

had been

slain, known as "tangata ika," or fish-man; the corpse was kept from

resting either day or night while his neighbours went in pursuit of

vengeance.

In front of one ahu, on the north coast, some pieces of the old statues

have

been formed into a rude chair. On this, it was said, had been seated

the naked

body of a man belonging to the district, Kotavari-vari by name, who had

been

killed at Akahanga on the south coast. One man kept the corpse from

falling,

while two others sat behind and chanted songs to aid the avengers.

These

watchers were covered with black ashes, wore only feather hats, and

carried the

small dancing-paddle known as "rapa" (fig. 116); the chief man in

charge of the ceremony was known as the "timo." It must have been an

eerie scene as dusk came on. The story is told of a murder near

Tongariki. In

this case the victim's corpse was placed on the ahu and turned over at

intervals by the watchers. Hanga Maihiko, a converted image ahu on the

south

coast, is one of those which have a paved approach, and there are on

the

pavement two stones — pieces of a hat and a statue — specially used for

exposing "fish-men" (fig. 93). If these charms failed to act, there

was a still more reliable way. The clothes of the victim were buried

beneath

the cooking-place of the foe, and when he had partaken of food prepared

there

he would certainly die the night following. Some of the carved tablets

were

connected with these rites; one was certainly known as that of the

"Ika,"

while there is said to have been another called "Timo," which was the

"list" kept by each ahu of its murdered men.  FIG. 93. — AHU, HANGA MAIHIKO Old Image, Ahu, converted to semi-pyramid form, with paved approach; also two stones on which were exposed the corpse of slain men. The

custom of exposing the dead was, as has been stated, going on in living

memory.

The information already given on this head is confirmed by the accounts

of the

missionaries,23 but burial was also practised,

the mode of disposal

being a matter of choice. There were two drawbacks to exposure:

firstly, if the

deceased was for any reason an uncanny person, his ghost might make

itself

unpleasant — he was safer hidden under stones; secondly, the body, if

left in

the open, might be burnt by enemies; this latter was the reason given

for the

burial of the last great chief, Ngaara, who was interred in one of the

image

ahu on the western coast. Not only were the ruins of the greater ahu

still

being used, but up till 1863 smaller ones were being built. One was

pointed out

on the north coast as having been put up for an individual, the

maternal aunt

of our guide, the lady having had the misfortune to be killed by a

devil in the

night. It was a small structure, ovoidal in shape, 10 feet in length,

with a

fiat top sloping from a height of 9 feet at the end towards the sea, to

4 feet

6 inches at that towards the land; there was beneath it a vaulted

chamber for

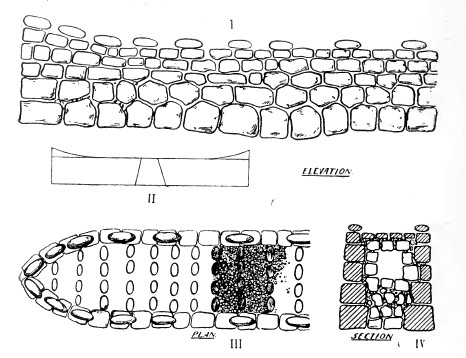

bones.  FIG. 94. DIAGRAM OF AHU POE-POE (CANOE-SHAPE). Burial

cairns, called "ahu poe-poe," were being made in modern times, and a

man skilled in their construction was amongst those who were carried

off to Peru.

The word "poe-poe" is described as meaning a big canoe, such as their

ancestors came in to the island. It is applied to two types of ahu, one

of

which is obviously built to resemble a boat; of this kind there are

about

twelve in the island. One large one (fig. 94) measured as much as 178

feet in

length, the width being 20 feet, while the ends, which are made like

the bow

and stern of a canoe, are about 10 feet to 15 feet in height. The flat

top is

paved with sea-boulders, and is surrounded by a row of the same in

imitation of

the gunwale of a boat. In one such ahu two vaults were found by us just

below

the surface with perfect burials. One was the body of an old man, the

other of

a woman with a child. Both had been wrapped in reeds, and with the body

of the

woman were some glass beads. On the surface of the ahu were a few

bones,

possibly of a body which had been exposed there, but the ahu had

apparently

been built for the two interments. It is less obvious why the same

name, “ahu

poe-poe," should be applied to a burial-place which was wedge-shaped in

form. It follows the lines of the image ahu in so far as having a wall

towards

the sea flanked on the land sides by a slope of masonry. It might be

held to

represent the prow of a boat, but resembles rather a pier or jetty.

Only some

six of these were seen, of which the longest was 70 feet. One in a

lonely spot,

at the very edge of a high cliff, which overlooked Anakena Bay, formed

a most

striking abode for the dead (fig. 95). In a few

cases the term ahu is given to a pavement, generally by the roadside,

neatly

made of rounded boulders and edged with a curb; the form was said to be

ancient. One of those on the west road was reported as specially

dedicated to

mata-toa — which signifies victors or warriors — and the same was said

of a

differently made ahu on the south coast .24 Neither

exposure nor interment was necessarily confined to ahu, and corpses

were

frequently disposed of in caverns, as in the case of Ko Tori. Three

instances

were mentioned, an uncle and two nephews, where the corpses, after

being

exposed, were lowered with a rope down the crevasses of the cliff of

Raraku in

order to evade the enemy. One of the nephews, who had been of the party

when

the final statues were overthrown, had met with a tragic end, being

drowned by

catching his hand in a rock when diving for lobsters under water. With

the

exception of those near the standing statues, we practically never

found an

earth burial. This seems to account for the exaggerated estimates of

the number

of human remains on the island; it is doubtful if even five hundred

skulls

could be collected, but, whether in caves or ruined ahu, a large

proportion of

those which exist are very much in evidence. Memorials

of the dead were erected in various places independently of the actual

locality

where the corpse rested. Some of these were simply mounds of earth,

which can

be seen on various hills; there is a regular succession on the landward

rim of

the Raraku crater, opposite to the great cliff, but one at least of

these was a

memorial to a man whose body had been disposed of in the clefts of the

cliff.

Others of these independent memorials were in the shape of cairns about

6 feet

in height, known as "pipi-hereko," and were formerly surmounted by a

white stone. Many of them still exist, and they are particularly

numerous on

the high ground above Anakena Cove. The locality was chosen as one

which was

but little inhabited, for the taboo for the dead (or pera) extended to

them,

and no one went near them in the daylight, on penalty of being stoned,

till the

period of mourning had been terminated with the usual feast. Various

voyagers

commented on these cairns, which were marked objects, and Cook thinks

that they

may have been put up instead of statues. It would

seem by the following tale, which imposes a somewhat severe strain on

the

European imagination, that piles of stones had in the native mind a

certain

resemblance to the human figure. “There was once an old lady who had an

arm so

long that it could have reached right across the island. She was a bad

old

woman, and once a month had a child to eat, so a certain man determined

to put

an end to her power for doing harm. He took her out in a boat to fish,

first

telling his small son to collect stones, and after they had gone to put

them in

piles in front of the house of the woman, and also to make a fire and

much

smoke. When the canoe had got out to sea, he looked back and found the

boy had

done as he was told, and glimpses of the cairns could be seen among the

clouds

of smoke. Then he called to the old woman, 'Look, there are men at your

house!'

So she put out her long arm to seize what she thought were the people

going to

rob her hut, whereon the man seized the paddle and brought it down on

her arm

and broke it; then he killed the old woman and threw her body into the

sea. Life was

by no means dull in Easter Island, for if a feast was not being given

to

commemorate a departed relation, it was arranged in honour of one

whilst still

alive. The "PAINA," which means simply picture or representation, was