| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

XI A NATIVE RISING It was

stated a little while back that we were left on the island with statues

and

natives. The statues remained quiescent, the natives did not. The

inhabitants,

or Kanakas to give them their usual name1 (fig. 26), are on

the

whole a handsome race, though their voices, particularly those of the

women,

are very harsh. They are fortunate also in possessing attractive

manners, from

which they get the full benefit in their intercourse with passing

ships. The

older people we found always kind and amiable, but the younger men have

a high

opinion of their own merits, and are often difficult to deal with.

Their

general morality, using the word in its limited sense, is, in common

with that

of all Polynesians, of a particularly low order; it is true that the

Europeans

with whom they have come into contact did not initiate this condition,

but they

have seldom done anything to show that that of their own lands is in

any way

higher; a fact which should be remembered when complaint is made that

Kanakas

"have no respect for white men." The native love of accuracy also

leaves a good deal to be desired, and their lies are astonishingly

fluent; but

lack of truthfulness is scarcely confined to Kanakas. In common with

all

residents in the South Seas, or indeed elsewhere, they exert themselves

no more

than is necessary to supply their wants; unfortunately these, save in

the

matter of clothes, have scarcely increased since pre-Christian days.

The

food-supply of sweet potatoes and bananas, with a few pigs and fowls,

can be

obtained with a minimum of labour; the keeping of sheep and cattle is

not

permitted by the Company, owing to the impossibility of discovering or

tracing

theft. Their old huts, which were made with sticks and grass, have been

replaced by small houses of wood or stone, but, except in a few cases,

there is

no furniture, and the inhabitants continue to sleep on the floor, in

company

with hens, which freely run in and out (fig. 27). There seems no desire

to

improve their condition; "Kanakas no like work, Kanakas like sit in

house," was the ingenuous reply given by one of them, when my husband

pointed out the good results which would accrue from planting some

trees in

village territory.  FIG. 26. — A GROUP OF EASTER ISLANDERS OUTSIDE THE CHURCH DOOR  FIG. 27. — HANGA ROA VILLAGE Native houses and church. Rano Kao in the distance. We had

heard in Chile rumours of native unrest, owing to the action of a white

man,

who had been for a short while on the island, and who had done his best

to

undermine the authority of the manager. We had before long unpleasant

evidence

that they were out of hand. The wool-shed, which contained our minutely

calculated stores, was broken into, and a quantity of things stolen,

the most lamented

being three-fourths of the stock of soap; no redress or punishment was

possible. On June 30th, while we were still at the manager's, a curious

development began which turned the history of the next five weeks into

a

Gilbertian opera — a play, however, with an undercurrent of reality

which made

the time the most anxious in the story of the Expedition. On that date

a

semi-crippled old woman, named Angata (fig. 30), came up to the

manager's house

accompanied by two men, and informed him that she had had a dream from

God,

according to which M. Merlet, the chairman of the Company, was "no

more," and the island belonged to the Kanakas, who were to take the

cattle

and have a feast the following day.2 Our party also was to

be laid

under contribution, which, it later transpired, was to take the form of

my

clothes. Later in the day the following declaration of war was formally

handed

in to Mr. Edmunds, written in Spanish as spoken on the island: "June

30th, 1914. "Senior

Ema, Mataveri, "Now

I declare to you, by-and-by we declare to you, which is the word we

speak

to-day, but we desire to take all the animals in the camp and all our

possessions in your hands, now, for you know that all the animals and

farm in

the camp belong to us, our Bishop Tepano gave to us originally. He gave

it to

us in truth and justice. There is another thing, the few animals which

are in

front of you,3 are for you to eat. There is also another

thing,

to-morrow we are going out into the camp to fetch some animals for a

banquet.

God for us. His truth and justice. There is also another business, but

we did

not receive who gave the animals to Merlet also who gave the earth to

Merlet

because it is a big robbery. They took this possession of ours, and

they gave

nothing for the earth, money or goods or anything else. They were never

given

to them. Now you know all that is necessary. "Your

friend, "Daniel

Antonio, “Hangaroa,"

If some

of the arguments are probably without foundation, as, for example, that

regarding native rights in the cattle, they were at least, as will be

seen, of

the same kind which have inspired risings in many lands and all ages.

The

delivery of the document was immediately followed by action. The

Kanakas went

into “the camp” eluding Mr. Edmunds, who had gone in another direction,

and

secured some ten head of cattle. The smoke from many fires was shortly

to be

seen ascending from the village, and one of our party was shown a beast

which

was to be offered to us in place of our stolen property, “God" having

apparently reversed his message on the subject of our contribution to

the new

republic. The next few days there was little more news "from the

front," save that Angata, the old woman, had had another dream, in

which

God had informed her that "He was very pleased that the Kanakas had

eaten

the meat and they were to eat some more." A week later, riding home

through the village, I saw a group on the green engaged in dressing a

girl's

hair; on inquiry it was found that she was to be married next day.

Congratulations had hardly been expressed, when another young woman was

pointed

out who was also to change her state at the same time, and another and

another,

till the prospective brides totalled five in all. The idea, it seemed,

was

prevalent, that if punishment was subsequently inflicted for the raids,

it was

the single men who would be taken to Chile, hence this rush into

matrimony,

undeterred by the fact that Mr. Edmunds, in his capacity as Chilean

official,

had declined for the present to perform the civil part of the ceremony.

The

wedding feast was, of course, to be furnished by the sheep of the

Company.

Unfortunately, under such circumstances, it seemed hardly loyal to our

host to

attend the multiple wedding, which was duly solemnised in the church

next day. Meanwhile,

the white residents had, of course, been considering their position,

and in

orthodox fashion, counting the number on which they could rely in an

emergency.

Beside Mr. Edmunds there were at this time in our party, myself and

five men:

S., Mr. Ritchie, the photographer, the cook, and a boy from Juan

Fernandez.

There were about half a dozen more or less reliable Kanakas, including

the

native Overseer and the village Headman, but everyone else was

involved. Mr.

Edmunds's position as custodian of the livestock was unenviable, and

ours was

not much more pleasant. After much thought we strongly dissuaded him

from

taking any action; if he interfered, there would be an affray. The

natives were

said to have a rifle and some pistols; it was doubtful how many would

go off, but

there would anyway be stone-throwing: if he was then forced to shoot,

the only

deterrent possible, he would have to continue till resistance was

entirely

cowed, or all our lives would remain in danger. His personal safety was

however

another matter, and our party therefore accompanied him in an attempt

to

frustrate a raid, but this obviously could not be continued if our work

was to

be accomplished. We were strengthened in adopting a waiting policy by

the fact

that, most fortunately, a fortnight earlier a passing vessel had left

us

newspapers; they confirmed the news heard in Chile that the naval

training-ship, the Jeneral Baquedano,

whose visits occurred at intervals of anything from two to five years,

was

shortly leaving for Easter Island. We could only hope her arrival would

be

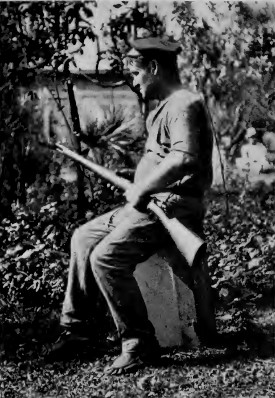

soon.  FIG 28. — BAILEY, THE COOK, ON GUARD S.

suggested that, being an unofficial person, he might meanwhile try the

effect

of negotiations; for the raids were continuing, and the head of cattle

killed

on one day had risen to fifty-six, including females and young. He

therefore

went down to the village, assembled the natives, and offered the

company a

present of two bullocks a week, if they would refrain from taking any

more

stock till the arrival of the warship, when the whole matter could be

referred

to the captain. The audience laughed the suggestion out of court, for

“the

whole of the cattle," they said, belonged to them, as God had told

Angata,

but they would let our party “have twenty" if we wished; as for Mr.

Edmunds, “he is a Protestant, and therefore, of course, has no God."  FIG 29. — EASTER ISLAND WOMEN When my

husband returned saying he had accomplished nothing, I felt that it was

"up to me." "This," I said, “is a matter requiring tact,

and is therefore a woman's job; I

will go and see the old lady." I had already received from her an

embarrassing present of fowls, which, after referring the matter to our

host,

it had seemed better to accept. Not without inward trepidation, I rode

down to

the village, taking the Fernandez boy as interpreter, for many of the

natives

speak a smattering of Spanish. The place was a perfect shambles, joints

of meat

hanging from all the trees, and skins being pegged out to dry on every

hand,

but the raiders had been displaying energy in rebuilding the wall round

the

church. The Prophetess was with a group outside the house of the acting

priest,

who was her son-in-law; she was a frail old woman with grey hair and

expressive

eyes, a distinctly attractive and magnetic personality. She wore

suspended

round her neck some sort of religious medallion, a red cross, I think,

on a

white ground, and her daughter who supported her carried a small

picture of the

Saviour in an Oxford frame. She held my hand most amiably during the

interview,

addressing me as "Caterina." I had brought her a gift and began by

thanking for the fowls. She refused all payments, saying "Food comes

from

God, I wish for no money," and proceeded to offer me some of the meat.

This gave an opening, and in declining I besought her not to let the

Kanakas go

out again after the animals, for Mr. Edmunds said he would shoot if

they did,

and there would be trouble for them when the Baquedano

came. As I spoke of the raids her face hardened and her

eyes took the look of a fanatic; she said something about "God" with

the upward gesture which was her habit in speaking His name. I hastened

to

relieve the tension by saying that “We must all worship God," and was

happy to find that I was allowed a share in the Deity. Her manner again

softened, and looking up to heaven she declared, with an assured

confidence,

which was in its way sublime, “God will never let the Kanakas be either

killed

or hurt." The natives were, in fact, firmly persuaded that no bullet

could

injure them. As for myself, Angata would, she said, “pray" for me,

adding,

with a descent to the mundane, that if ever she had "chickens or

potatoes," I should be the first to have them. It was impossible to

reason

further; we parted the best of friends, but the "tactful" mission had

failed! This was

the state of affairs when we decided that we must transfer our work and

consequently our belongings to the other end of the island. Our

surveyor and

photographer remained, however, at Mataveri, as the accommodation there

was

more convenient for their occupations, so Mr. Edmunds was not alone.

Moving

camp, levelling ground, and building walls, were not light matters,

when the

Kanakas had found such much more interesting employment, but at last it

was

accomplished, and then came the question of the stores, which after the

robbery

at the woolshed had been taken to Mataveri. After much consultation it

was

decided to remove them to Raraku, as on the whole safer than leaving

them at

the manager's house, which might, by the look of things, be any day

looted or

burnt down. But when the ox-cart had been carefully loaded up with the

numerous

boxes and goods, the cash supply, consisting of £50 of English gold and

some

Chilean paper, being carefully hidden amongst them, a spell of bad

weather set

in. It was impossible to move the cart, and our possessions sat there

day after

day most handily arranged for the revolutionists if their desires

should turn

that way.  FIG 30. — ANGATA, THE PROPHETESS. Our new

camp we were often obliged to leave without defence save for the

redoubtable

Bailey, who had also served as guard at Mataveri (fig. 28). There had

been no

demonstration against us so far, but of course the future was unknown,

and I

never came in sight of our house, on returning from any distant work,

without casting

an anxious glance to see if it were still standing. We always went

about armed,

and the different ranges for rifle-shot were measured off from my house

and

marked by cairns, which will no doubt in future add yet one more to the

mysteries of Easter Island. One day I

had just come back from a stroll, when the cry was raised "The Kanakas

are

coming," and a troop of horsemen, about thirty strong, appeared on the

sky-line some four hundred yards distant. Fortunately S. was at hand,

we

hurried inside my house, shut the lower half of its door, which

resembled that

of a loose-box, and carelessly leant out. Any unpleasantness could then

only be

frontal; at the same time all weapons were within easy grasp, though

not

visible from the outside. It soon,

however, became clear that the visitors were approaching at a walk

only, from

which it was gathered their intentions were friendly. Nevertheless it

was a

relief when, as they got nearer, they raised their hats and gave a

cheer; they

then formed a semi-circle round the door and dismounted. The "priest"

who was with them, and who carried a picture of the Virgin, read

something,

presumably a prayer, at which the company crossed themselves. He then

gave

greetings from Angata, and a message from her to say that Mana

was returning safely with letters on board, and the men

presented from their saddle-bows, eggs, potatoes, and about a dozen

hens. The

position was unwelcome, but as none of the goods were stolen, it seemed

better

to accept, and discharge the obligation as far as possible by giving in

return

what European food we could spare. We

subsequently informed Mr. Edmunds, and sent a message to the Prophetess

that,

as our camp was out of bounds, the Kanakas must not come without leave.

The old

lady herself, however, kept sending to us for anything she happened to

want,

and as the requests continually grew in magnitude the breaking-point

seemed

only a question of time. One of the earlier demands, to which Mr.

Edmunds

thought it advisable we should accede, was for material for a flag for

the new

Republic; later, it floated proudly as a tricolour, made of a piece of

white

cotton, some red material from the photographic outfit, and a fragment

of an

old blue shirt. Elsewhere

things went from bad to worse, and it seemed as if the expected warship

would

never arrive. Word came that the Kanakas had ordered the native

overseer to

leave his house, the only one outside the village, and were taking away

the

servants of the manager; our photographer wrote that he "dared not come

over as their lives were being threatened"; and finally, one afternoon

we

received a note from Mr. Edmunds, saying, that "he could not leave the

place as the Kanakas were talking of coming up in a body to the house."

They were also, as we later learnt, threatening to kill him if he

resisted

their taking possession. It was obvious that the crisis had arrived;

that we

must risk leaving the camp and go into Mataveri. We talked over every

conceivable plan of campaign, but it was too late to do anything that

night, and

I remember that, finally at dinner, to turn our thoughts, we discussed

the

curious manner in which some of the statues had fallen. In four cases

which we

had seen that day, while the body lay on its front, the head had broken

off in

mid air, turned a complete somersault, and rested on its back with the

crown

towards the neck. The next morning, August 5th, I awoke early and

recorded in

my journal the events of the day before. “Of course," I added, “if it

were

a stage play, just as the crisis arrived there would be cries of ‘the Baquedano is here,' and the curtain

would fall. But, alas! it is not." Scarcely was the ink dry — only it

was

pencil — when a man rode up waving a note from Mr. Edmunds, and

shouting, “A

ship! — a ship!” The previous afternoon, as the Kanakas were assembling

in the

village to go up to Mataveri, the Baquedano

had been sighted, and four of the ringleaders were now in irons. I

scarcely

knew how great had been the long strain till the relief came. Our

rejoicings, however, we found to have been partly premature. The

warship had

unfortunately brought with her large gifts of clothes for the natives

from

well-wishers in Chile. Some little while before attention had been

'drawn to

the inhabitants of Easter, by an Australian captain who had touched

there on

his homeward voyage. The natives had, as usual, come off to his ship in

their

oldest garments; he had been impressed with their ragged condition and

made a

collection of clothes for them in Australia amounting to many bales,

but on his

next voyage to Chile he had been unable to touch again at the island

and had

left them at Valparaiso. We had been asked to bring these bales, but

had

declined on the score of space.4 The Chileans disliked the

idea of

their protectorate being indebted to strangers, made a collection on

their own

account, and despatched them by the Baquedano.

It seemed unthinkable that people, every one of whom for weeks had been

consuming stolen goods, and who, two days before, had been on the verge

of

murder, should be immediately presented officially with the commodity

they most

prized. I therefore went on board the Baquedano,

saw the Captain, and ventured to request that the goods should be

handed over

to us, promising personally to visit every house before our departure,

ascertain

the needs of the people, and distribute the articles. “Surely," he

said, “you

shall have them." Within a few hours they had been distributed by his

officers on the beach. Some of the garments were useful, but an

assortment of

ball-slippers seemed a little out of place, and the greater part of the

community, men and women, blossomed out into washing waistcoats. The

stolen

sheepskins, or some of them, were returned, but three of the four

ringleaders

were set at liberty, and no corporate punishment was inflicted; indeed,

the

Captain had told me he considered that the natives had “behaved very

well not

to murder Mr. Edmunds" prior to our arrival. Before

the ship left the island, the Captain wrote officially to the "Head of

the

British Scientific Expedition" to the effect, that the action he had

been

obliged to take to restore order would probably have the result of

rousing more

feeling against foreigners; he therefore could not guarantee our safety

and

offered us passages to Chile — an offer which, needless to say, we

declined. So

ended the Revolution; we felt with interest that the confidence of the

Prophetess had been justified, at any rate as far as 249 Kanakas were

concerned

out of the 250. The old

lady died six months later; I attended her funeral. The coffin was

pathetically

tiny, and neatly covered with black and white calico. A service was

first held

in the church where, during the rising, she used to take part in the

assemblies

and address her adherents. There figured prominently in the ceremony a

model of

the building and also two prie-dieu, roughly made of boards, one of

which she

had used in private, the other in public worship. She was laid to rest

beneath

the great wooden cross, which marks the Kanaka burying-ground, between

the

village and the bay. I stood at a little distance watching gleams of

sunshine

on the great stones of the terrace of Hanga Roa and on the grey sea

beyond, and

musing on the strange life now closed, whose early days had been spent

in a

native hut beneath the standing images of Raraku. My attention was

recalled by

an evident hitch in the proceedings: difficulty had arisen in lowering

the

coffin, owing to the fact that the prie-dieu was also being fitted into

the

grave. When all had been finally adjusted and the interment was

completed, a

sound was heard, unusual in such circumstances — three English cheers —

hip,

hip, hooray; the natives had learnt it from passing ships and esteemed

it an

essential part of a ceremony. The company was not large for the

obsequies of

one who had so recently been the heroine of the village, and on asking

in

particular why a certain near relative was absent, the answer received

was that

"there was to be a great feast of pigs, and he was busy preparing it";

doubtless others were similarly detained. During

the remainder of our sojourn there were, as will be seen, additional

white men

on the island. The Kanakas were occupied in various ways and there was

no

further open demonstration, but their independence and demands

increased daily.

Since we left, a white employee of the Company has been murdered by

them and

thrown into the sea. 1

"Kanaka" is a name originally given by Europeans to the inhabitants

of the South Seas, and is one form of the Polynesian word meaning

"man" 2 The

natives of Easter hold very firmly the primitive belief in dreams. If

one of

them dreamt, for example, that Mana

was returning, it was retailed to us with all the assurance of a

wireless

message. 3 The

milch-cows. 4

Considerably later Mana was again

approached on the subject of the Australian gifts, and Mr. Gillam

consented to

bring them; it then transpired that they were no longer available,

having

"been given by the wife of the head of the Customs to the deserving

poor

of Valparaiso." |