| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

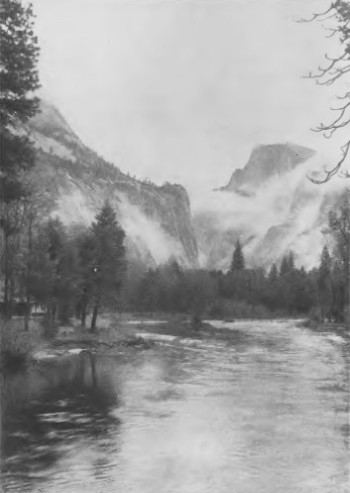

CHAPTER V THE YOSEMITE July 15. Followed the Mono Trail up the eastern rim of the basin nearly to its summit, then turned off southward to a small shallow valley that extends to the edge of the Yosemite, which we reached about noon, and encamped. After luncheon I made haste to high ground, and from the top of the ridge on the west side of Indian Canon gained the noblest view of the summit peaks I have ever yet enjoyed. Nearly all the upper basin of the Merced was displayed, with its sublime domes and canons, dark up sweeping forests, and glorious array of white peaks deep in the sky, every feature glowing, radiating beauty that pours into our flesh and bones like heat rays from fire. Sunshine over all; no breath of wind to stir the brooding calm. Never before had I seen so glorious a landscape, so boundless an affluence of sublime mountain beauty. The most extravagant description I might give of this view to any one who has not seen similar landscapes with his own eyes would not so much as hint its grandeur and the spiritual glow that covered it. I shouted and gesticulated in a wild burst of ecstasy, much to the astonishment of St. Bernard Carlo, who came running up to me, manifesting in his intelligent eyes a puzzled concern that was very ludicrous, which had the effect of bringing me to my senses. A brown bear, too, it would seem, had been a spectator of the show I had made of my self, for I had gone but a few yards when I started one from a thicket of brush. He evidently considered me dangerous, for he ran away very fast, tumbling over the tops of the tangled manzanita bushes in his haste. Carlo drew back, with his ears depressed as if afraid, and kept looking me in the face, as if expecting me to pursue and shoot, for he had seen many a bear battle in his day. Following the ridge, which made a gradual descent to

the south, I came at length to the brow of that massive cliff that stands

between Indian Canon and Yosemite Falls, and here the far-famed valley came

suddenly into view throughout almost its whole extent. The no ble walls

sculptured into endless variety of domes and gables, spires and battlements and

plain mural precipices all a-tremble with the thunder tones of the falling

water. The level bottom seemed to be dressed like a garden sunny meadows here

and there, and groves of pine and oak; the river of Mercy sweeping in majesty

through the midst of them and flashing back the sunbeams. The great Tissiack,

or Half-Dome, rising at the upper end of the valley to a height of nearly a

mile, is nobly proportioned and life-like, the most impressive of all the

rocks, holding the eye in devout admiration, calling it back again and again

from falls or meadows, or even the mountains be yond, marvelous cliffs, marvelous

in sheer dizzy depth and sculpture, types of endurance. Thousands of years have

they stood in the sky exposed to rain, snow, frost, earth quake and avalanche,

yet they still wear the bloom of youth. I rambled along the valley rim to the westward; most

of it is rounded off on the very brink, so that it is not easy to find places

where one may look clear down the face of the wall to the bottom. When such

places were found, and I had cautiously set my feet and drawn my body erect, I

could not help fearing a little that the rock might split off and let me down,

and what a down! more than three thousand feet. Still my limbs did not

tremble, nor did I feel the least uncertainty as to the reliance to be placed

on them. My only fear was that a flake of the granite, which in some places

showed joints more or less open and running parallel with the face of the

cliff, might give way. After withdrawing from such places, excited with the

view I had got, I would say to myself, "Now don't go out on the verge again."

But in the face of Yosemite scenery cautious remonstrance is vain; under its

spell one's body seems to go where it likes with a will over which we seem to

have scarce any control. After a mile or so of this memorable cliff work I

approached Yosemite Creek, admiring its easy, graceful, confident gestures as

it comes bravely forward in its narrow channel, singing the last of its

mountain songs on its way to its fate a few rods more over the shining

granite, then down half a mile in showy foam to an other world, to be lost in

the Merced, where climate, vegetation, inhabitants, all are different. Emerging

from its last gorge, it glides in wide lace-like rapids down a smooth incline

into a pool where it seems to rest and compose its gray, agitated waters before

taking the grand plunge, then slowly slipping over the lip of the pool basin,

it descends another glossy slope with rapidly accelerated speed to the brink of

the tremendous cliff, and with sublime, fateful confidence springs out free in

the air. I took off my shoes and stockings and worked my way

cautiously down alongside the rushing flood, keeping my feet and hands pressed

firmly on the polished rock. The booming, roaring water, rushing past close to

my head, was very exciting. I had expected that the sloping apron would

terminate with the perpendicular wall of the valley, and that from the foot of

it, where it is less steeply inclined, I should be able to lean far enough out

to see the forms and behavior of the fall all the way down to the bottom. But I

found that there was yet another small brow over which I could not see, and

which appeared to be too steep for mortal feet. Scanning it keenly, I

discovered a narrow shelf about three inches wide on the very brink, just wide

enough for a rest for one's heels. But there seemed to be no way of reaching it

over so steep a brow. At length, after careful scrutiny of the surface, I found

an irregular edge of a flake of the rock some distance back from the margin of

the torrent. If I was to get down to the brink at all that rough edge, which

might offer slight finger-holds, was the only way. But the slope beside it

looked dangerously smooth and steep, and the swift roaring flood beneath,

overhead, and beside me was very nerve-trying. I therefore concluded not to venture

farther, but did nevertheless. Tufts of artemisia were growing in clefts of the

rock near by, and I filled my mouth with the bitter leaves, hoping they might

help to prevent giddiness. Then, with a caution not known in ordinary

circumstances, I crept down safely to the little ledge, got my heels well

planted on it, then shuffled in a horizontal direction twenty or thirty feet

until close to the outplunging current, which, by the time it had descended

thus far, was already white. Here I obtained a perfectly free view down into

the heart of the snowy, chanting throng of comet-like streamers, into which the

body of the fall soon separates. While perched on that narrow niche I was not

distinctly conscious of danger. The tremendous grandeur of the fall in form and

sound and motion, acting at close range, smothered the sense of fear, and in

such places one's body takes keen care for safety on its own account. How long

I remained down there, or how I returned, I can hardly tell. Anyhow I had a

glorious time, and got back to camp about dark, enjoying triumphant

exhilaration soon followed by dull weariness. Hereafter I'll try to keep from

such extravagant, nerve-straining places. Yet such a day is well worth

venturing for. My first view of the High Sierra, first view looking down into

Yosemite, the death song of Yosemite Creek, and its flight over the vast cliff,

each one of these is of itself enough for a great life-long landscape fortune

a most memorable day of days enjoyment enough to kill if that were possible. July 16. My enjoyments yesterday after noon, especially at

the head of the fall, were too great for good sleep. Kept starting up last

night in a nervous tremor, half awake, fancying that the foundation of the

mountain we were camped on had given way and was falling into Yosemite Valley.

In vain I roused myself to make a new beginning for sound sleep. The nerve

strain had been too great, and again and again I dreamed I was rushing through

the air above a glorious avalanche of water and rocks. One time, springing to

nay feet, I said, "This time it is real all must die, and where could

mountaineer find a more glorious death!" Left camp soon after sunrise for an all-day ramble

eastward. Crossed the head of Indian Basin, forested with Abies magnifica,

under brush mostly Ceanothus cordulatus and manzanita, a mixture

not easily trampled over or penetrated, for the ceanothus is thorny and grows

in dense snow-pressed masses, and the manzanita has exceedingly crooked, stub

born branches. From the head of the canon continued on past North Dome into the

basin of Dome or Porcupine Creek. Here are many fine meadows imbedded in the

woods, gay with Lilium parvum and its companions; the elevation, about

eight thousand feet, seems to be best suited for it saw specimens that were a

foot or two higher than my head. Had more magnificent views of the upper

mountains, and of the great South Dome, said to be the grandest rock in the

world. Well it may be, since it is of such noble dimensions and sculpture. A

wonderfully impressive monument, its lines exquisite in fineness, and though

sublime in size, is finished like the fin est work of art, and seems to be

alive. July 17. A new camp was made to-day in a magnificent silver fir grove at the head of a small stream that flows into Yosemite by way of Indian Canon. Here we intend to stay several weeks, a fine location from which to make excursions about the great valley and its fountains. Glorious days I'll have sketch ing, pressing plants, studying the wonderful topography and the wild animals, our happy fellow mortals and neighbors. But the vast mountains in the distance, shall I ever know them, shall I be allowed to enter into their midst and dwell with them? We were pelted about noon by a short, heavy

rainstorm, sublime thunder reverberating among the mountains and canons, some

strokes near, crashing, ringing in the tense crisp air with startling keenness,

while the distant peaks loomed gloriously through the cloud fringes and sheets

of rain. Now the storm

is past, and the fresh washed air is full of the essences of the flower gardens

and groves. Winter storms in Yosemite must be glorious. May I see them!  The North and South Domes Have got my bed made in our new camp, plushy,

sumptuous, and deliciously fragrant, most of it magnifica fir plumes, of

course, with a variety of sweet flowers in the pillow. Hope to sleep to-night

without tottering nerve-dreams. Watched a deer eating ceanothus leaves and

twigs. July 18. Slept pretty well; the valley walls did not seem

to fall, though I still fancied my self at the brink, alongside the white,

plunging flood, especially when half asleep. Strange the danger of that

adventure should be more troublesome now that I am in the bosom of the peaceful

woods, a mile or more from the fall, than it was while I was on the brink of

it. Bears seem to be common here, judging by their

tracks. About noon we had another rainstorm with keen startling thunder, the

metallic, ringing, clashing, clanging notes gradually fading into low bass rolling

and muttering in the distance. For a few minutes the rain came in a grand

torrent like a water fall, then hail; some of the hailstones an inch in

diameter, hard, icy, and irregular in form, like those oftentimes seen in

Wisconsin. Carlo watched them with intelligent astonishment as they came

pelting and thrashing through the quivering branches of the trees. The cloud

scenery sublime. Afternoon calm, sunful, and clear, with delicious freshness

and fragrance from the firs and flowers and steaming ground. July 19. Watching the daybreak and sun rise. The pale rose

and purple sky changing softly to daffodil yellow and white, sunbeams pouring

through the passes between the peaks and over the Yosemite domes, making their

edges burn; the silver firs in the middle ground catching the glow on their

spiry tops, and our camp grove fills and thrills with the glorious light.

Everything awakening alert and joy ful; the birds begin to stir and innumerable

insect people. Deer quietly withdraw into leafy hiding-places in the chaparral;

the dew vanishes, flowers spread their petals, every pulse beats high, every

life cell rejoices, the very rocks seem to thrill with life. The whole land

scape glows like a human face in a glory of enthusiasm, and the blue sky, pale

around the horizon, bends peacefully down over all like one vast flower. About noon, as usual, big bossy cumuli be gan to grow

above the forest, and the rain storm pouring from them is the most imposing I

have yet seen. The silvery zigzag lightning lances are longer than usual, and

the thunder gloriously impressive, keen, crashing, intensely concentrated,

speaking with such tremendous energy it would seem that an entire mountain is

being shattered at every stroke, but probably only a few trees are being

shattered, many of which I have seen on my walks here abouts strewing the

ground. At last the clear ringing strokes are succeeded by deep low tones that

grow gradually fainter as they roll afar into the recesses of the echoing

mountains, where they seem to be welcomed home. Then another and another peal,

or rather crashing, splintering stroke, follows in quick succession, perchance

splitting some giant pine or fir from top to bottom into long rails and

slivers, and scattering them to all points of the compass. Now comes the rain,

with corresponding extravagant grandeur, covering the ground high and low with

a sheet of flowing water, a transparent film fitted like a skin upon the rugged

anatomy of the landscape, making the rocks glitter and glow, gathering in the

ravines, flooding the streams, and making them shout and boom in reply to the

thunder. How interesting to trace the history of a single

raindrop! It is not long, geologically speaking, as we have seen, since the

first rain drops fell on the newborn leafless Sierra landscapes. How different

the lot of these falling now! Happy the showers that fall on so fair a

wilderness, scarce a single drop can fail to find a beautiful spot, on the

tops of the peaks, on the shining glacier pavements, on the great smooth domes,

on forests and gardens and brushy moraines, plashing, glinting, pattering,

laving. Some go to the high snowy fountains to swell their well-saved stores;

some into the lakes, washing the mountain windows, patting their smooth glassy

levels, making dimples and bubbles and spray; some into the waterfalls and

cascades, as if eager to join in their dance and song and beat their foam yet

finer; good luck and good work for the happy mountain raindrops, each one of

them a high waterfall in itself, descending from the cliffs and hollows of the

clouds to the cliffs and hollows of the rocks, out of the sky-thunder into the

thunder of the falling rivers. Some, falling on meadows and bogs, creep

silently out of sight to the grass roots, hiding softly as in a nest, slipping,

oozing hither, thither, seeking and finding their appointed work. Some,

descending through the spires of the woods, sift spray through the shining

needles, whispering peace and good cheer to each one of them. Some drops with

happy aim glint on the sides of crystals, quartz, hornblende, garnet, zircon,

tourmaline, feldspar, patter on grains of gold and heavy way-worn nuggets;

some, with blunt plap-plap and low bass drumming, fall on the broad leaves of

veratrum, saxifrage, cypripedium. Some happy drops fall straight into the cups

of flowers, kissing the lips of lilies. How far they have to go, how many cups

to fill, great and small, cells too small to be seen, cups holding half a drop

as well as lake basins between the hills, each replenished with equal care,

every drop in all the blessed throng a silvery newborn star with lake and

river, garden and grove, valley and mountain, all that the landscape holds

reflected in its crystal depths, God's messenger, angel of love sent on its way

with majesty and pomp and display of power that make man's greatest shows

ridiculous. Now the storm is over, the sky is. clear, the last

rolling thunder-wave is spent on the peaks, and where are the raindrops now

what has become of all the shining throng? In winged vapor rising some are

already hastening back to the sky, some have gone into the plants, creeping

through invisible doors into the round rooms of cells, some are locked in

crystals of ice, some in rock crystals, some in porous moraines to keep their

small springs flowing, some have gone journeying on in the rivers to join the

larger raindrop of the ocean. From form to form, beauty to beauty, ever

changing, never resting, all are speeding on with love's enthusiasm, singing

with the stars the eternal song of creation. July 20. Fine calm morning; air tense and clear; not the

slightest breeze astir; every thing shining, the rocks with wet crystals, the

plants with dew, each receiving its portion of irised dewdrops and sunshine

like living creatures getting their breakfast, their dew manna coming down from

the starry sky like swarms of smaller stars. How wondrous fine are the

particles in showers of dew, thousands required for a single drop, growing in

the dark as silently as the grass! What pains are taken to keep this wilderness

in health, showers of snow, showers of rain, showers of dew, floods of light,

floods of invisible vapor, clouds, winds, all sorts of weather, interaction of

plant on plant, animal on animal, etc., beyond thought! How fine Nature's methods!

How deeply with beauty is beauty overlaid! the ground covered with crystals,

the crystals with mosses and lichens and low-spreading grasses and flowers,

these with larger plants leaf over leaf with ever-changing color and form, the

broad palms of the firs outspread over these, the azure dome over all like a

bell-flower, and star above star. Yonder stands the South Dome, its crown high above

our camp, though its base is four thousand feet below us; a most noble rock, it

seems full of thought, clothed with living light, no sense of dead stone about

it, all spiritualized, neither heavy looking nor light, steadfast in serene

strength like a god. Our shepherd is a queer character and hard to place

in this wilderness. His bed is a hollow made in red dry-rot punky dust beside a

log which forms a portion of the south wall of the corral. Here he lies with

his wonderful ever lasting clothing on, wrapped in a red blanket, breathing not

only the dust of the decayed wood but also that of the corral, as if determined

to take ammoniacal snuff all night after chewing tobacco all day. Following the

sheep he carries a heavy six-shooter swung from his belt on one side and his

luncheon on the other. The ancient cloth in which the meat, fresh from the

frying-pan, is tied serves as a filter through which the clear fat and gravy

juices drip down on his right hip and leg in clustering stalactites. This

oleaginous formation is soon broken up, however, and diffused and rubbed evenly

into his scanty apparel, by sitting down, rolling over, crossing his legs while

resting on logs, etc., making shirt and trousers water-tight and shiny. His

trousers, in particular, have become so adhesive with the mixed fat and resin

that pine needles, thin flakes and fibres of bark, hair, mica scales and minute

grains of quartz, hornblende, etc., feathers, seed wings, moth and butterfly

wings, legs and antennae of innumerable insects, or even whole insects such as

the small beetles, moths and mosquitoes, with flower petals, pollen dust and

indeed bits of all plants, animals, and minerals of the region adhere to them

and are safely imbedded, so that though far from being a naturalist he collects

fragmentary specimens of everything and becomes richer than he knows. His

specimens are kept passably fresh, too, by the purity of the air and the resiny

bituminous beds into which they are pressed. Man is a microcosm, at least our

shepherd is, or rather his trousers. These precious overalls are never taken

off, and no body knows how old they are, though one may guess by their

thickness and concentric structure. Instead of wearing thin they wear thick,

and in their stratification have no small geological significance. Besides herding the sheep, Billy is the butcher,

while I have agreed to wash the few iron and tin utensils and make the bread.

Then, these small duties done, by the time the sun is fairly above the

mountain-tops I am beyond the flock, free to rove and revel in the wilderness

all the big immortal days. Sketching on the North Dome. It commands views of

nearly all the valley besides a few of the high mountains. I would fain draw

everything in sight rock, tree, and leaf. But little can I do beyond mere

outlines, marks with meanings like words, readable only to myself, yet I

sharpen my pencils and work on as if others might possibly be benefited.

Whether these picture-sheets are to vanish like fallen leaves or go to friends

like letters, matters not much; for little can they tell to those who have not

themselves seen similar wildness, and like a language have learned it. No pain

here, no dull empty hours, no fear of the past, no fear of the future. These

blessed mountains are so compactly filled with God's beauty, no petty personal

hope or experience has room to be. Drinking this champagne water is pure

pleasure, so is breathing the living air, and every movement of limbs is

pleasure, while the whole body seems to feel beauty when exposed to it as it

feels the camp-fire or sunshine, entering not by the eyes alone, but equally

through all one's flesh like radiant heat, making a passionate ecstatic

pleasure-glow not explainable. One's body then seems homogeneous throughout,

sound as a crystal. Perched like a fly on this Yosemite dome, I gaze and

sketch and bask, oftentimes settling down into dumb admiration without definite

hope of ever learning much, yet with the long ing, unresting effort that lies

at the door of hope, humbly prostrate before the vast dis play of God's power,

and eager to offer self-denial and renunciation with eternal toil to learn any lesson

in the divine manuscript. It is easier to feel than to realize, or in any way

explain, Yosemite grandeur. The magnitudes of the rocks and trees and streams

are so delicately harmonized they are mostly hidden. Sheer precipices three

thousand feet high are fringed with tall trees growing close like grass on the

brow of a lowland hill, and extending along the feet of these precipices a

ribbon of meadow a mile wide and seven or eight long, that seems like a strip a

farmer might mow in less than a day. Waterfalls, five hundred to one or two

thousand feet high, are so subordinated to the mighty cliffs over which they

pour that they seem like wisps of smoke, gentle as floating clouds, though

their voices fill the valley and make the rocks tremble. The mountains, too,

along the eastern sky, and the domes in front of them, and the succession of

smooth rounded waves between, swelling higher, higher, with dark woods in their

hollows, serene in massive exuberant bulk and beauty, tend yet more to hide the

grandeur of the Yosemite temple and make it appear as a subdued subordinate

feature of the vast harmonious landscape. Thus every attempt to appreciate any

one feature is beaten down by the overwhelming influence of all the others.

And, as if this were not enough, lo! in the sky arises another mountain range

with topography as rugged and substantial-looking as the one beneath it snowy

peaks and domes and shadowy Yosemite valleys another version of the snowy

Sierra, a new creation heralded by a thunder-storm. How fiercely, devoutly wild

is Nature in the midst of her beauty-loving tenderness! painting lilies,

watering them, caressing them with gentle hand, going from flower to flower

like a gardener while building rock mountains and cloud mountains full of lightning

and rain. Gladly we run for shelter beneath an over hanging cliff and examine

the reassuring ferns and mosses, gentle love tokens growing in cracks and

chinks. Daisies, too, and ivesias, confiding wild children of light, too small

to fear. To these one's heart goes home, and the voices of the storm become

gentle. Now the sun breaks forth and fragrant steam arises. The birds are out

singing on the edges of the groves. The west is flaming in gold and purple,

ready for the ceremony of the sunset, and back I go to camp with my notes and

pictures, the best of them printed in my mind as dreams. A fruitful day,

without measured beginning or ending. A terrestrial eternity. A gift of good

God. Wrote to my mother and a few friends, mountain hints

to each. They seem as near as if within voice-reach or touch. The deeper the

solitude the less the sense of loneliness, and the nearer our friends. Now

bread and tea, fir bed and good-night to Carlo, a look at the sky lilies, and

death sleep until the dawn of another Sierra to-morrow. July 21. Sketching on the Dome no rain; clouds at noon

about quarter filled the sky, casting shadows with fine effect on the white

mountains at the heads of the streams, and a soothing cover over the gardens

during the warm hours. Saw a common house-fly and a grasshopper and a brown

bear. The fly and grasshopper paid me a merry visit on the top of the Dome, and

I paid a visit to the bear in the middle of a small garden meadow between the

Dome and the camp where he was standing alert among the flowers as if willing

to be seen to advantage. I had not gone more than half a mile from camp this

morning, when Carlo, who was trotting on a few yards ahead of me, came to a

sudden, cautious standstill. Down went tail and ears, and forward went his knowing

nose, while he seemed to be saying, "Ha, what's this? A bear, I

guess." Then a cautious advance of a few steps, setting his feet down

softly like a hunting cat, and questioning the air as to the scent he had

caught until all doubt vanished. Then he came back to me, looked me in the

face, and with his speaking eyes reported a bear near by; then led on softly,

careful, like an experienced hunter, not to make the slightest noise, and

frequently looking back as if whispering, "Yes, it's a bear; come and I'll

show you." Presently we came to where the sunbeams were streaming through

between the purple shafts of the firs, which showed that we were nearing an

open spot, and here Carlo came behind me, evidently sure that the bear was very

near. So I crept to a low ridge of moraine boulders on the edge of a narrow

garden meadow, and in this meadow I felt pretty sure the bear must be. I was

anxious to get a good look at the sturdy mountaineer without alarming him; so

drawing myself up noiselessly back of one of the largest of the trees I peered

past its bulging buttresses, exposing only a part of my head, and there stood

neighbor Bruin within a stone's throw, his hips covered by tall grass and

flowers, and his front feet on the trunk of a fir that had fallen out into the

meadow, which raised his head so high that he seemed to be standing erect. He

had not yet seen me, but was looking and listening attentively, showing that in

some way he was aware of our approach. I watched his gestures and tried to make

the most of my opportunity to learn what I could about him, fearing he would

catch sight of me and run away. For I had been told that this sort of bear, the

cinnamon, always ran from his bad brother man, never showing fight unless

wounded or in defense of young. He made a telling picture standing alert in the

sunny forest garden. How well he played his part, harmonizing in bulk and color

and shaggy hair with the trunks of the trees and lush vegetation, as natural a

feature as any other in the landscape. After examining at leisure, noting the

sharp muzzle thrust inquiringly forward, the long shaggy hair on his broad

chest, the stiff, erect ears nearly buried in hair, and the slow, heavy way he

moved his head, I thought I should like to see his gait in running, so I made a

sudden rush at him, shouting and swinging my hat to frighten him, expecting to

see him make haste to get away. But to my dismay he did not run or show any

sign of running. On the contrary, he stood his ground ready to fight and defend

himself, lowered his head, thrust it forward, and looked sharply and fiercely

at me. Then I suddenly began to fear that upon me would fall the work of

running; but I was afraid to run, and therefore, like the bear, held my ground.

We stood staring at each other in solemn silence within a dozen yards or there

abouts, while I fervently hoped that the power of the human eye over wild

beasts would prove as great as it is said to be. How long our aw fully

strenuous interview lasted, I don't know; but at length in the slow fullness of

time he pulled his huge paws down off the log, and with magnificent

deliberation turned and walked leisurely up the meadow, stopping frequently to

look back over his shoulder to see whether I was pursuing him, then moving on

again, evidently neither fearing me very much nor trusting me. He was probably

about five hundred pounds in weight, a broad, rusty bundle of ungovernable

wildness, a happy fellow whose lines have fallen in pleasant places. The

flowery glade in which I saw him so well, framed like a picture, is one of the

best of all I have yet discovered, a conservatory of Nature's precious plant

people. Tall lilies were swinging their bells over that bear's back, with geraniums, larkspurs,

columbines, and daisies brushing against his sides. A place for angels, one would say, instead of bears.

In the great canons Bruin reigns supreme. Happy fellow, whom no famine can reach while one of his thousand kinds of food is spared him. His bread is sure at all seasons, ranged on the mountain shelves like stores in a pantry. From one to the other, up or down he climbs, tasting and enjoying each in turn in different climates, as if he had journeyed thousands of miles to other countries north or south to enjoy their varied productions. I should like to know my hairy brothers better though after this particular Yosemite bear, my very neighbor, had sauntered out of sight this morning, I reluctantly went back to camp for the Don's rifle to shoot him, if necessary, in defense of the flock. Fortunately I couldn't find him, and after tracking him a mile or two towards Mount Huffman I bade him Godspeed and gladly returned to my work on the Yosemite Dome. The house-fly also seemed at home and buzzed about me as I sat sketching, and

enjoying my bear interview now it was over. I

wonder what draws house-flies so far up the mountains, heavy gross feeders as they are, sensitive to cold, and fond of domestic

ease. How have they been distributed

from continent to continent, across seas and deserts and mountain chains, usually so influential in

determining boundaries of species both of plants and animals. Beetles and butterflies are some times restricted to small areas. Each

mountain in a range, and even the different zones of a mountain, may have its own peculiar species. But the house-fly seems to be

every where. I wonder if any island in

mid-ocean is flyless. The bluebottle is

abundant in these Yosemite woods, ever

ready with his marvelous store of eggs to make all dead flesh fly. Bumblebees are here, and are well fed

on boundless stores of nectar and

pollen. The honeybee, though abundant

in the foothills, has not yet got so

high. It is only a few years since the

first swarm was brought to

California. A queer fellow and a jolly fellow is the grass hopper. Up the mountains he comes on excursions, how high I don't know, but at least as far and high as Yosemite tourists. I was much interested with the hearty enjoyment of the one that danced and sang for me on the Dome this afternoon. He seemed brimful of glad, hilarious energy, manifested by springing into the air to a height of twenty or thirty feet, then diving and springing up again and making a sharp musical rattle just as the lowest point in the descent was reached. Up and down a dozen times or so he danced and sang, then alighted to rest, then up and at it again. The curves he described in the air in diving and rattling resembled those made by cords hanging loosely and attached at the same height at the ends, the loops nearly covering each other. Braver, heartier, keener, care-free enjoyment of life I have never seen or heard in any creature, great or small. The life of this comic red-legs, the mountain's merriest child, seems to be made up of pure, condensed gayety. The Douglas squirrel is the only living creature that I can compare him with in exuberant, rollicking, irrepressible jollity. Wonderful that these sublime mountains are so loudly cheered and brightened by a creature so queer. Nature in him seems to be snapping her fingers in the face of all earthly dejection and melancholy with a boyish hip-hip-hurrah. How the sound is made I do not understand. When he was on the ground he made not the slightest noise, nor when he was simply flying from place to place, but only when diving in curves, the motion seeming to be required for the sound; for the more vigorous the diving the more energetic the corresponding outbursts of jolly rattling. I tried to observe him closely while he was resting in the intervals of his performances; but he would not allow a near approach, always getting his jumping legs ready to spring for immediate flight, and keeping his eyes on me. A fine sermon the little fellow danced for me on the Dome, a likely place to look for sermons in stones, but not for grasshopper sermons. A large and imposing pulpit for so small a preacher. No danger of weakness in the knees of the world while Nature can spring such a rattle as this. Even the bear did not express for me the mountain's wild health and strength and happiness so tellingly as did this comical little hopper. No cloud of care in his day, no winter of discontent in sight. To him every day is a holiday; and when at length his sun sets, I fancy he will cuddle down on the forest floor and die like the leaves and flowers, and like them leave no unsightly remains calling for burial.  TRACK OF SINGING DANCING GRASSHOPPER IN THE AIR OVER NORTH DOME Sundown, and I must to camp. Good-night, friends three, brown bear, rugged

boulder of energy in groves and gardens

fair as Eden; restless, fussy fly with

gauzy wings stirring the air around all

the world; and grasshopper, crisp,

electric spark of joy enlivening the massy

sublimity of the mountains like the laugh of a child. Thank you, thank you all three for your quickening company. Heaven guide

every wing and leg. Good-night friends

three, good night. July 22. A fine specimen of the black-tailed deer went bounding past camp this

morning. A buck with wide spread of

antlers, showing admirable vigor and

grace. Wonderful the beauty, strength,

and graceful movements of animals in

wildernesses, cared for by Nature only,

when our experience with domestic animals would lead us to fear that all the

so-called neglected wild beasts would

degenerate. Yet the upshot of Nature's

method of breeding and teaching seems

to lead to excellence of every sort.

Deer, like all wild animals, are as clean

as plants. The beauties of their gestures and attitudes, alert or in repose, surprise yet more than their bounding exuberant strength.

Every movement and posture is graceful,

the very poetry of manners and motion.

Mother Nature is too often spoken of as

in reality no mother at all. Yet how

wisely, sternly, tenderly she loves and

looks after her children in all sorts of

weather and wildernesses. The more I see of deer the more I admire them as mountaineers. They make their way

into the heart of the roughest

solitudes with smooth reserve of

strength, through dense belts of brush and forest encumbered with fallen trees and boulder piles, across canons, roaring streams, and

snowfields, ever showing forth beauty and courage. Over nearly all the continent the deer find homes. In the Florida savannas and hummocks,

in the Canada woods, in the far north,

roaming over mossy tundras, swimming lakes and rivers and arms of the sea from island to island washed with waves, or climbing

rocky mountains, everywhere healthy and

able, adding beauty to every landscape,a truly admirable creature and great

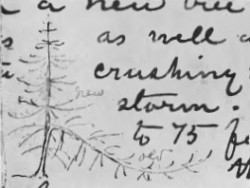

credit to Nature.  MOUNT CLARK, TOP OF SOUTH DOME, MOUNT STAAR KING ABIES MAGNIFICA Have been sketching a silver fir that stands on a granite ridge a few hundred yards to

the eastward of campa fine tree with a

particular snow-storm story to tell. It

is about one hundred feet high, growing on bare rock, thrusting its roots into

a weathered joint less than an inch

wide, and bulging out to form a base to

bear its weight. The storm came from the north while it was young and broke it down nearly to the ground, as is shown by the

old, dead, weather-beaten top leaning

out from the living trunk built up from

a new shoot below the break. The annual

rings of the trunk that have overgrown

the dead sapling tell the year of the

storm. Wonderful that a side branch

forming a portion of one of the level collars that encircle the trunk of this species (Abies magnifica)

should bend upward, grow erect, and

take the place of the lost axis to form a

new tree. Many others, pines as well as firs, bear testimony to

the crushing severity of this particular

storm. Trees, some of them fifty to seventy-five feet high, were bent to

the ground and buried like grass, whole

groves vanishing as if the forest had

been cleared away, leaving not a branch

or needle visible until the spring thaw.

Then the more elastic undamaged saplings rose again, aided by the wind, some reaching a nearly erect attitude, others remaining more

or less bent, while those with broken

backs endeavored to specialize a side branch below the break and make a leader of it to form a new

axis of development. It is as if a man,

whose back was broken or nearly so and

who was compelled to go bent, should find a branch back bone sprouting straight up from below

the break and should gradually develop

new arms and shoulders and head, while

the old dam aged portion of his body

died. Grand white cloud mountains and domes created about noon as usual, ridges and

ranges of endless variety, as if Nature

dearly loved this sort of work, doing

it again and again nearly every day

with infinite industry, and producing

beauty that never palls. A few zigzags of

lightning, five minutes' shower, then a

gradual wilting and clearing.  ILLUSTRATING GROWTH OF NEW PINE FROM BRANCH BELOW THE BREAK OF AXIS OF SNOW-CRUSHED TREE July 23. Another midday cloudland, displaying power and

beauty that one never wearies in beholding, but hopelessly unsketchable and untellable. What can poor mortals

say about clouds? While a description

of their huge glowing domes and ridges,

shadowy gulfs and canons, and

feather-edged ravines is being tried,

they vanish, leaving no visible ruins.

Nevertheless, these fleeting sky mountains are as substantial and significant as the more lasting upheavals of granite beneath them.

Both alike are built up and die, and in

God's calendar difference of duration

is nothing. We can only dream about

them in wondering, worshiping

admiration, happier than we dare tell even to friends who see farthest in sympathy, glad to know that not a crystal or vapor particle

of them, hard or soft, is lost; that

they sink and vanish only to rise again

and again in higher and higher beauty.

As to our own work, duty, influence,

etc., concerning which so much fussy

pother is made, it will not fail of its due effect, though, like a lichen on a stone, we

keep silent. July 24. Clouds at noon occupying about half the sky gave half an hour of heavy rain to wash one of the cleanest landscapes in the world. How well it is washed! The sea is hardly less dusty than the ice-burnished pavements and ridges, domes and canons, and summit peaks plashed with snow like waves with foam. How fresh the woods are and calm after the last films of clouds have been wiped from the sky! A few minutes ago every tree was excited, bowing to the roaring storm, waving, swirling, tossing their branches in glorious enthusiasm like worship. But though to the outer ear these trees are now silent, their songs never cease. Every hidden cell is throbbing with music and life, every fibre thrilling like harp strings, while .incense is ever flowing from the balsam bells and leaves. No wonder the hills and groves were God's first temples, and the more they are cut down and hewn into cathedrals and churches, the farther off and dimmer seems the Lord himself. The same may be said of stone temples. Yonder, to the eastward of our camp grove, stands one of Nature's cathedrals, hewn from the living rock, almost conventional in form, about two thousand feet high, nobly adorned with spires and pinnacles, thrilling under floods of sunshine as if alive like a grove- temple, and well named "Cathedral Peak." Even Shepherd Billy turns at times to this wonderful mountain building, though apparently deaf to all stone sermons. Snow that refused to melt in fire would hardly be more wonderful than unchanging dullness in the rays of God's beauty. I have been trying to get him to walk to the brink of Yosemite for a view, offering to watch the sheep for a day, while he should enjoy what tourists come from all over the world to see. But though within a mile of the famous valley, he will not go to it even out of mere curiosity. "What," says he, "is Yosemite but a canon a lot of rocks a hole in the ground a place dangerous about falling into a dd good place to keep away from." "But think of the waterfalls, Billy just think of that big stream we crossed the other day, falling half a mile through the air think of that, and the sound it makes. You can hear it now like the roar of the sea." Thus I pressed Yosemite upon him like a missionary offering the gospel, but he would have none of it. "I should be afraid to look over so high a wall," he said. "It would make my head swim. There is nothing worth seeing anywhere, only rocks, and I see plenty of them here. Tourists that spend their money to see rocks and falls are fools, that's all. You can't humbug me. I've been in this country too long for that." Such souls, I suppose, are asleep, or smothered and befogged beneath mean pleasures and cares. July 25. Another cloudland. Some

clouds have an over-ripe decaying look,

watery and bedraggled and drawn out

into wind-torn shreds and patches,

giving the sky a littered appearance;

not so these Sierra summer mid day

clouds. All are beautiful with smooth definite outlines and curves like those

of glacier-polished domes. They begin to grow about eleven o'clock, and seem so wonderfully near and clear from this high camp one is tempted to try to climb them and trace the streams

that pour like cataracts from their

shadowy fountains. The rain to which they give birth is often very heavy, a sort of waterfall as imposing

as if pouring from rock mountains.

Never in all my travels have I found

anything more truly novel and

interesting than these midday mountains

of the sky, their fine tones of color, majestic visible growth, and ever-changing scenery

and general effects, though mostly as

well let alone as far as description

goes. I oftentimes think of Shelley's

cloud poem, "I sift the snow on the

mountains below." |