| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

XIV THE POETIC JUNE-BUG, TOGETHER WITH SOME REMARKS ON THE GILLYHOOLY BIRD "Uncle Munch," said Diavolo one

afternoon as a couple of bicyclers sped past the house at breakneck speed,

"which would you rather have, a bicycle or a horse?" "Well, I must say, my

boy, that is a difficult question to answer," Mr. Munchausen replied after

scratching his head dubiously for a few minutes. "You might as well ask a

man which he prefers, a hammock or a steam-yacht. To that question I should

reply that if I wanted to sell it, I'd rather have a steam-yacht, but for a

pleasant swing on a cool piazza in midsummer or under the apple-trees, a

hammock would be far preferable. Steam-yachts are not much good to swing in

under an apple tree, and very few piazzas that I know of are big enough — " "Oh, now, you know

what I mean, Uncle Munch," Diavolo retorted, tapping Mr. Munchausen upon

the end of his nose, for a twinkle in Mr. Munchausen's eye seemed to indicate

that he was in one of his chaffing moods, and a greater tease than Mr.

Munchausen when he felt that way no one has ever known. "I mean for horse-back

riding, which would you rather have?" "Ah, that's another

matter," returned Mr. Munchausen, calmly. "Now I know how to answer

your question. For horse-back riding I certainly prefer a horse; though, on the

other hand, for bicycling, bicycles are better than horses. Horses make very

poor bicycles, due no doubt to the fact that they have no wheels." Diavolo began to grow

desperate. "Of course," Mr.

Munchausen went on, "all I have to say in this connection is based merely

on my ideas, and not upon any personal experience. I've been horse-back riding

on horses, and bicycling on bicycles, but I never went horse-back riding on a

bicycle, or bicycling on horseback. I should think it might be exciting to go bicycling

on horse-back, but very dangerous. It is hard enough for me to keep a bicycle

from toppling over when I'm riding on a hard, straight, level well-paved road,

without experimenting with my wheel on a horse's back. However if you wish to

try it some day and will get me a horse with a back as big as Trafalgar Square

I'm willing to make the effort." Angelica giggled. It was

lots of fun for her when Mr. Munchausen teased Diavolo, though she didn't like

it quite so much when it was her turn to be treated that way. Diavolo wanted to

laugh too, but he had too much dignity for that, and to conceal his desire to

grin from Mr. Munchausen he began to hunt about for an old newspaper, or a lump

of coal or something else he could make a ball of to throw at him. "Which would you

rather do, Angelica," Mr. Munchausen resumed, "go to sea in a balloon

or attend a dumb-crambo party in a chicken-coop?" "I guess I

would," laughed Angelica. "That's a good

answer," Mr. Munchausen put in. "It is quite as intelligent as the

one which is attributed to the Gillyhooly bird. When the Gillyhooly bird was

asked his opinion of giraffes, he scratched his head for a minute and said, "'The question hath but little wit That you have put to me, But I will try to answer it With prompt candidity. The automobile is a thing That's pleasing to the mind; And in a lustrous diamond ring Some merit I can find. Some persons gloat o'er French Chateaux; Some dote on lemon ice; While others gorge on mixed gateaux, Yet have no use for mice. I'm very fond of oyster-stew, I love a patent-leather boot, But after all, 'twixt me and you, The fish-ball is my favourite fruit.'" "Hoh" jeered

Diavolo, who, attracted by the allusion to a kind of bird of which he had never

heard before, had given up the quest for a paper ball and returned to Mr.

Munchausen's side, "I don't think that was a very intelligent answer. It

didn't answer the question at all." "That's true, and that

is why it was intelligent," said Mr. Munchausen. "It was

noncommittal. Some day when you are older and know less than you do now, you

will realise, my dear Diavolo, how valuable a thing is the reply that answereth

not." Mr. Munchausen paused long

enough to let the lesson sink in and then he resumed. "The Gillyhooly bird

is a perfect owl for wisdom of that sort," he said. "It never lets

anybody know what it thinks; it never makes promises, and rarely speaks except

to mystify people. It probably has just as decided an opinion concerning

giraffes as you or I have, but it never lets anybody into the secret." "What is a Gillyhooly

bird, anyhow?" asked Diavolo. "He's a bird that

never sings for fear of straining his voice; never flies for fear of wearying

his wings; never eats for fear of spoiling his digestion; never stands up for

fear of bandying his legs and never lies down for fear of injuring his

spine," said Mr. Munchausen. "He has no feathers, because, as he

says, if he had, people would pull them out to trim hats with, which would be

painful, and he never goes into debt because, as he observes himself, he has no

hope of paying the bill with which nature has endowed him, so why run up

others?" "I shouldn't think

he'd live long if he doesn't eat?" suggested Angelica. "That's the great

trouble," said Mr. Munchausen. "He doesn't live long. Nothing so

ineffably wise as the Gillyhooly bird ever does live long. I don't believe a

Gillyhooly bird ever lived more than a day, and that, connected with the fact

that he is very ugly and keeps himself out of sight, is possibly why no one has

ever seen one. He is known only by hearsay, and as a matter of fact, besides

ourselves, I doubt if any one has ever heard of him." Diavolo eyed Mr. Munchausen

narrowly. "Speaking of

Gillyhooly birds, however, and to be serious for a moment," Mr. Munchausen

continued flinching nervously under Diavolo's unyielding gaze; "I never

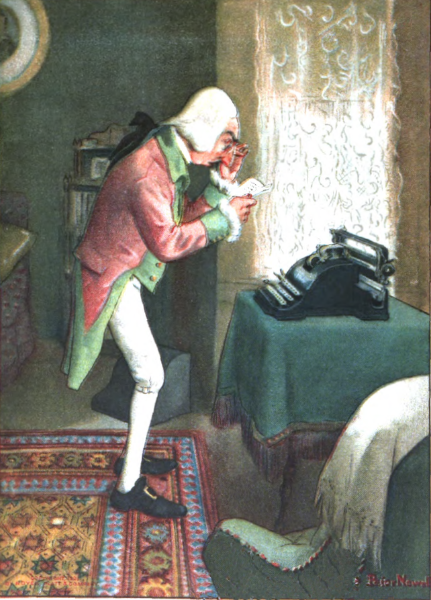

told you about the poetic June-bug that worked the typewriter, did I?" "Never heard of such a

thing," cried Diavolo. "The idea of a June-bug working a

typewriter." "I don't believe

it," said Angelica, "he hasn't got any fingers." "That shows all you

know about it," retorted Mr. Munchausen. "You think because you are

half-way right you are all right. However, if you don't want to hear the story

of the June-bug that worked the type-writer, I won't tell it. My tongue is

tired, anyhow." "Please go on,"

said Diavolo. "I want to hear it." "So do I," said

Angelica. "There are lots of stories I don't believe that I like to hear — 'Jack the Giant-killer' and

'Cinderella,' for instance." "Very well," said

Mr. Munchausen. "I'll tell it, and you can believe it or not, as you

please. It was only two summers ago that the thing happened, and I think it was

very curious. As you may know, I often have a great lot of writing to do and

sometimes I get very tired holding a pen in my hand. When you get old enough to

write real long letters you'll know what I mean. Your writing hand will get so

tired that sometimes you'll wish some wizard would come along smart enough to

invent a machine by means of which everything you think can be transferred to

paper as you think it, without the necessity of writing. But as yet the only

relief to the man whose hand is worn out by the amount of writing he has to do

is the use of the type-writer, which is hard only on the fingers. So to help me

in my work two summers ago I bought a type-writing machine, and put it in the

great bay-window of my room at the hotel where I was stopping. It was a magnificent

hotel, but it had one drawback — it

was infested with June-bugs. Most summer hotels are afflicted with mosquitoes,

but this one had June-bugs instead, and all night long they'd buzz and butt their

heads against the walls until the guests went almost crazy with the noise. "At first I did not

mind it very much. It was amusing to watch them, and my friends and I used to

play a sort of game of chance with them that entertained us hugely. We marked

the walls off in squares which we numbered and then made little wagers as to

which of the squares a specially selected June-bug would whack next. To

simplify the game we caught the chosen June-bug and put some powdered charcoal

on his head, so that when he butted up against the white wall he would leave a black

mark in the space he hit. It was really one of the most exciting games of that

particular kind that I ever played, and many a rainy day was made pleasant by

this diversion. "But after awhile like

everything else June-bug Roulette as we called it began to pall and I grew

tired of it and wished there never had been such a thing as a June-bug in the

world. I did my best to forget them, but it was impossible. Their buzzing and

butting continued uninterrupted, and toward the end of the month they developed

a particularly bad habit of butting the electric call button at the side of my

bed. The consequence was that at all hours of the night, hall-boys with

iced-water, and house-maids with bath towels, and porters with kindling-wood

would come knocking at my door and routing me out of bed — summoned of course by none other than those horrible butting

insects. This particular nuisance became so unendurable that I had to change my

room for one which had no electric bell in it. "So things went, until

June passed and July appeared. The majority of the nuisances promptly got out

but one especially vigorous and athletic member of the tribe remained. He

became unbearable and finally one night I jumped out of bed either to kill him

or to drive him out of my apartment forever, but he wouldn't go, and try as I might

I couldn't hit him hard enough to kill him. In sheer desperation I took the

cover of my typewriting machine and tried to catch him in that. Finally I

succeeded, and, as I thought, shook the heedless creature out of the window

promptly slamming the window shut so that he might not return; and then putting

the type-writer cover back over the machine, I went to bed again, but not to

sleep as I had hoped. All night long every second or two I'd hear the

type-writer click. This I attributed to nervousness on my part. As far as I

knew there wasn't anything to make the type-writer click, and the fact that I

heard it do so served only to convince me that I was tired and imagined that I heard

noises.  "Most singular of all was the fact that consciously or unconsciously the insect had butted out a verse." "The next morning,

however, on opening the machine I found that the June-bug had not only not been

shaken out of the window, but had actually spent the night inside of the cover,

butting his head against the keys, having no wall to butt with it, and most

singular of all was the fact that, consciously or unconsciously, the insect had

butted out a verse which read: "'I'm glad I haven't any brains, For there can be no doubt I'd have to give up butting If I had, or butt them out.'" "Mercy! Really?"

cried Angelica. "Well I can't prove

it," said Mr. Munchausen, "by producing the June-bug, but I can show

you the hotel, I can tell you the number of the room; I can show you the

type-writing machine, and I have recited the verse. If you're not satisfied

with that I'll have to stand your suspicions." "What became of the

June-bug?" demanded Diavolo. "He flew off as soon

as I lifted the top of the machine," said Mr. Munchausen. "He had all

the modesty of a true poet and did not wish to be around while his poem was

being read." "It's queer how you

can't get rid of June-bugs, isn't it, Uncle Munch," suggested Angelica. "Oh, we got rid of 'em

next season all right," said Mr. Munchausen. "I invented a scheme

that kept them away all the following summer. I got the landlord to hang

calendars all over the house with one full page for each month. Then in every

room we exposed the page for May and left it that way all summer. When the

June-bugs arrived and saw these, they were fooled into believing that June hadn't

come yet, and off they flew to wait. They are very inconsiderate of other

people's comfort," Mr. Munchausen concluded, "but they are rigorously

bound by an etiquette of their own. A self-respecting June-bug would no more appear

until the June-bug season is regularly open than a gentleman of high society

would go to a five o'clock tea munching fresh-roasted peanuts. And by the way,

that reminds me I happen to have a bag of peanuts right here in my

pocket." Here Mr. Munchausen,

transferring the luscious goobers to Angelica, suddenly remembered that he had

something to say to the Imps' father, and hurriedly left them. "Do you suppose that's

true, Diavolo?" whispered Angelica as their friend disappeared. "Well it might

happen," said Diavolo, "but I've a sort of notion that it's 'maginary

like the Gillyhooly bird. Gimme a peanut." |