| CHICKEN-DIDDLE

One

day Chicken-diddle had gone to sleep under a rose-bush, and a cow

reached over

the fence and bit off the top of the rose-bush. The noise wakened

Chicken-diddle, and just as she woke a rose-leaf fell on her tail.

“Squawk!

Squawk!” cried Chicken-diddle, “the sky’s falling down”; and away she

ran as

fast as her legs would carry her. She ran until she came to the

barnyard, and

there was Hen-pen rustling in the dust of the barnyard.

“Oh,

Hen-pen, don’t rustle — run, run!” cried Chicken-diddle. “The sky’s

falling

down.”

The

hen stopped rustling. “How do you know that Chicken-diddle?” asked

Hen-pen.

“I

saw it with my eyes, I heard it with my ears, and part of it fell on my

tail.

Oh, let us run, run, until we get some place.”

“Quawk!

Quawk,” cried the hen, and she began to run, and Chicken-diddle ran

after her.

They

ran till they came to the duck-pond, and there was Duck-luck just going

in for

a swim.

“Oh,

Duck-luck! Duck-luck! don’t try to swim,” cried Hen-pen. “The sky’s

falling

down.”

“How

do you know that, Hen-pen?” asked Duck-luck.

“Chicken-diddle

told me.”

“How

do you know that, Chicken-diddle?”

“Why

shouldn’t I know it? I saw it with my eyes, I heard it with my ears,

and part

of it fell on my tail. Oh, let us run, run until we get some place.”

“Yes,

we had better run,” quacked Duck-luck, and away he waddled with

Hen-pen, and

Chicken-diddle after him.

They

ran and ran till they came to a green meadow, and there was Goose-loose

eating

the green grass.

“Oh,

Goose-loose, Goose-loose, don’t eat; run, run,” cried Duck-luck.

“Why

should I run?” asked Goose-loose.

“Because

the sky’s falling down.”

“How

do you know that, Duck-luck?”

“Hen-pen

told me.”

“How

do you know that, Hen-pen?”

“Chicken-diddle

told me.”

“How

do you know that, Chicken-diddle?”

“Because

I saw it with my eyes, and heard it with my ears, and part of it fell

on my

tail. Oh, let us run, run some place.”

“Yes,

we’d better run,” cried Goose-loose.

Away

they all ran, Goose-loose at the head of them, and they ran and ran

until they

came to the turkey-yard, and there was Turkey-lurkey strutting and

gobbling.

“Oh,

Turkey-lurkey! don’t strut! Don’t strut!” cried Goose-loose.

“Why

should I not strut?” asked Turkey-lurkey.

“Because

the sky’s falling down.”

“How

do you know it is?”

“Duck-luck

told me!”

“How

do you know, Duck-luck?”

“Hen-pen

told me!”

“How

do you know, Hen-pen?”

“Chicken-diddle

told me!”

“How

do you know, Chicken-diddle?”

“I

couldn’t help knowing! I saw it with my eyes, I heard it with my ears,

and a

part of it fell on my tail. Oh, let us run, run until we get some

place.”

“Yes,

we’d better run,” said Turkey-lurkey, so away they all ran, first

Turkey-lurkey, and then Goose-loose, and then Duck-luck, and then

Hen-pen, and

then Chicken-diddle.

They

ran and ran until they came to Fox-lox’s house, and there was Fox-lox

lying in

the doorway and yawning until his tongue curled up in his mouth. When

he saw

Turkey-lurkey and Goose-loose and Duck-luck and Hen-pen and

Chicken-diddle he

stopped yawning, and pricked up his ears, and he was very glad to see

them.

“Well,

well,” said he, “and what brings you all here?”

“Oh,

Fox-lox, Fox-lox, don’t yawn,” cried Turkey-lurkey, “the sky’s falling

down.”

“How

do you know that, Turkey-lurkey?” asked the fox.

“Goose-loose

told me.”

“How

do you know that, Goose-loose?”

“Duck-luck

told me.”

“How

do you know that, Duck-luck?”

“Hen-pen

told me.”

“How

do you know that, Hen-pen?”

“Chicken-diddle

told me.”

“How

do you know that, Chicken-diddle?”

“I

couldn’t help knowing, for I saw it with my eyes, and I heard it with

my ears,

and part of it fell on my tail. Oh, where shall we run? We ought to go

some

place.”

“Well,”

said the Fox, “you come right in here, and I’ll take such good care of

you that

even if the sky falls down you won’t know anything about it.”

So in

ran Turkey-lurkey, and Fox-lox put him in the big room, and shut the

door. In

ran Goose-loose, and he put him in the little room, and shut the door.

In ran

Duck-luck, and he put him in the cellar, and shut the door. In ran

Hen-pen, and

he put her in the attic, and shut the door. In ran Chicken-diddle, and

Fox-lox

kept him right there in the room with him. And what happened to them

after that

I don’t know, but nobody ever saw them again; if the sky really fell, I

never

heard about it. They were only a pack of silly fowls, anyway.

A PACK OF RAGAMUFFINS

“My

dear,” said the cock to the hen one day, “what do you say to our taking

a walk

over to Mulberry Hill? The mulberries must be ripe by now, and we can

have a

fine feast.”

“That

would suit me exactly,” answered the hen. “I am very fond of ripe

fruit, and it

is a long time since I have tasted any.” So the cock and hen set off

together.

The

way was long, and the day was hot, and before the two had reached the

top of

the hill they were both of them tired and out of breath. The mulberries

lay

thick on the ground, and the cock and the hen ran about hither and yon,

pecking

and eating — pecking and eating, until they could eat no more, and the

sun was

near setting.

“Oh!

oh!” groaned the hen, “how weary I am. How in the world are we to get

home

again. My legs are so tired, I could not go another step if my life

depended on

it.”

“My

dear,” said the cock, “I too am weary, but I see here a number of

fallen twigs.

If I could but weave them into a coach we might ride home in comfort.”

“That

is a clever thought,” sighed the hen. “Make it by all means. There is

nothing I

like better than riding in a coach.”

The

cock at once set to work, and by weaving sticks and grasses together he

made a

little coach with body, wheels, and shafts all complete.

The

hen was delighted. She at once hopped into the coach, and seated

herself. “Now,

my dear Cock-a-lorum,” she cried, “nothing more is needed but for you

to get

between the shafts and step out briskly, and we will be at home in less

than no

time.”

“What

are you talking about?” asked the cock sharply. “I have no idea of

pulling the

coach myself. My legs ache as well as yours, and if you wait for me to

pull you

home you may sit there till doomsday.”

“But

how then are we to get home?” asked the hen, beginning to weep.

“I do

not know,” answered the cock. “But what I do know is that I am not

going to

pull you.”

“But

you must pull me,” wept the hen.

“But

I won’t pull you,” stormed the cock.

So

they scolded and disputed and there is no knowing how it would have

ended, but

suddenly a duck appeared from behind some bushes.

When

the duck saw the hen and the cock it ruffled up its feathers and

waddled toward

them, quacking fiercely. “What is this! What is this!” cried the duck.

“Do you

not know that this hill belongs to me? Be off at once or I will give

you a

sound beating.”

It

flew at the cock with outspread wings. The cock, however, was a brave

little

fellow. Instead of running away he met the duck valiantly, and seizing

it he

pulled out a beakful of feathers. The hen shrieked, but the cock

continued to

punish the duck until it cried for mercy.

“Very

well,” said the cock, settling his feathers. “I will let you go this

time, but

only if you will promise to draw our coach to the nearest inn, where we

can

spend the night.”

The

duck was afraid to refuse the cock’s demand. He put himself between the

shafts,

the cock mounted the coach and cracked his whip, and away they all went

as fast

as the duck could waddle. The coach rocked and bumped over the stones,

and

suddenly the duck gave a jump that almost upset it. “Ouch! ouch!” it

cried.

“Something stuck me.”

“I do

well to stick you,” replied a small sharp voice. “I may teach you to

look where

you are going, and not step on honest travelers who are smaller than

you.”

The

voice was that of a needle, who, with a pin for a comrade, was

journeying along

the same road.

The

cock looked out from the coach. “I am sorry,” said he, “that my duck

should be

so careless. Will you not get in and ride with us?”

This

the pin and the needle were glad to do. The hen was somewhat nervous at

first,

lest one of them might tread on her foot, but they were so polite, and

so

careful not to crowd her, that she soon lost her fear of them.

Just

before nightfall the coach reached the door of an inn. Here the duck

stopped,

and the cock called loudly for the landlord.

The

man came running, but when he saw the strange guests that sat in the

coach he

almost shut the door on them. “We want no ragamuffins here,” he cried.

“Wait

a bit,” cried the cock. “Just see this fine white egg that the hen has

laid.

And every morning the duck lays an egg also. Both of these shall be

yours if

you will take us in for the night.”

Well,

the landlord was willing to agree to that bargain. He bade the

companions enter

and make themselves comfortable. This they did, eating and drinking to

their

hearts’ content. Then the cock and the hen made themselves comfortable

in the

best bed, and the others tucked themselves away as best they could.

As

soon as they were all asleep the landlord said to his wife, “Listen!

This is a

fine bargain that I have made. Roast duck is very good, and so is

chicken pie,

and to-morrow our travelers shall furnish us with both of them. As for

the

needle and pin you can put them away in your work-basket, and they will

always

be useful.”

After

saying this the landlord and his wife also went to sleep, for the

landlord

intended to be up early in the morning before his guests had wakened.

The

cock, however, was not one to let anyone catch him sleeping. While it

was still

dark the next morning, he awakened the hen. “Come,” said he; “we’d best

be up

and away. This landlord of ours seems to me a sly and greedy man; he

might take

a notion to have roast chicken for dinner to-day, so we had better be

gone

before he is stirring.”

To

this the hen agreed, but she and the cock were both hungry, so before

starting

they shared the egg between them. The shells they threw in among the

ashes on

the hearth. Then they took the needle and stuck it in the back of the

landlord’s chair; the pin they put in the towel that hung behind the

door, and

this done they took to their wings and away they flew.

The

sound of their going awoke the duck. It opened its eyes and looked

after them.

“Well, well! So they’re off. I think I’d better be moving myself,” and

so

saying it waddled down to the river, and swam back to the place whence

it had

come.

It

was not long after this the landlord himself awoke. “I’ll just slip

down and

see to the travelers before breakfast,” said he.

“Do,”

answered his wife.

First,

however, the landlord stopped to wash in the kitchen. He picked up the

towel to

dry his face, and the pin that was in it scratched him from ear to ear.

He went

to the hearth to light his pipe and the egg-shells flew up in his face.

He sat

down in his chair for a moment, but scarcely had he leaned back, when

he jumped

up with a cry. The needle had run into him.

“It

is all the fault of those ragamuffins,” cried the landlord in a rage,

and he

caught up a knife and ran to find them. But search as he might there

was not a

sign of them anywhere, for they were already safely home again.

So

all the landlord had for his trouble after all, was his pains.

THE FROG

PRINCE

There

was once a king who had one only daughter, and her he loved as he loved

the

apple of his eye.

One

day the Princess sat beside a fountain in the gardens, and played with

a golden

ball. She threw it up into the air and caught it again, and the ball

shone and

glittered in the sunshine so that she laughed aloud with pleasure. But

presently as she caught at the ball she missed it, and it rolled across

the

grass and fell into the fountain. There it sank to the bottom. The

Princess

tried and tried to reach it, but she could not. Then she began to weep,

and her

tears dripped down into the fountain.

“Princess,

Princess, why are you weeping?” asked a hoarse voice.

The

Princess looked about her, and there was a great squat green frog

sitting on

the edge of the fountain.

“I am

weeping, Froggie, because I have dropped my ball into the water and I

cannot

get it again,” answered the Princess.

“And

what will you give me if I get it for you?”

“Anything

in the world, dear Frog, except the ball itself.”

“I

wish you to give me nothing, Princess,” said the frog. “But if I bring

back

your ball to you will you let me be your little playmate? Will you let

me sit

at your table, and eat from your plate, and drink from your mug, and

sleep in

your little bed?”

“Yes,

yes,” cried the Princess. She was very willing to promise, for she did

not

believe the frog could ever leave the fountain, or come up the palace

steps.

“Very

well, then that is a promise,” said the frog, and at once he plunged

into the

fountain and brought back the ball to the Princess in his arms.

The

little girl took the ball and ran away with it without even stopping to

thank

him.

That

evening the child sat at supper with her father, and she ate from her

golden

plate, and drank from her golden mug, and she did not even give a

thought to

the frog down in the fountain.

Presently

there came a knocking at the door, but it was so soft that no one heard

it but

the Princess. Then the knocking came again, and a hoarse voice cried,

“King’s

daughter, King’s daughter, let me in. Have you forgotten the promise

you made

me by the fountain?”

The

Princess was frightened. She slipped down from her chair, and ran to

the door,

and opened it and looked out. There on the top-most step sat the great

green

frog.

When

the Princess saw him she shut the door quickly, and came back to the

table, and

she was very pale.

“Who

was that at the door?” asked the King.

“It

was no one,” answered the Princess.

“But

there was surely someone there,” said the King.

“It

was only a great green frog from the fountain,” said the Princess. And

then she

told her father how she had dropped her ball into the fountain, and how

the

frog had brought it back to her, and of what she had promised him.

“What

you have promised that you must perform,” said the King. “Open the

door, my

daughter, and let him in.”

Very

unwillingly the child went back to the door and opened it; the frog

hopped into

the room. When she returned to the table, the frog hopped along close

at her

heels.

She

sat down and began to eat. “King’s daughter, King’s daughter, set me

upon the

table that I too may eat from your golden plate,” said the frog.

The

Princess would have refused, but she dared not because of what her

father had

said. She lifted the frog to the table, and there he ate from her

plate, but

she herself could touch nothing.

“I am

thirsty,” said the frog. “Tilt your golden mug that I may drink from

it.”

The

Princess did as he bade her, but as she did so she could not help

weeping so

that her tears ran down into the milk.

When

supper was ended the Princess was about to hurry away to her room, but

the frog

called to her, “King’s daughter, King’s daughter, take me along. Have

you

forgotten that I was to sleep in your little white bed?”

“That

you shall not,” cried the Princess in a passion. “Go back to the stones

of the

fountain, where you belong.”

“What

you have said that you must do,” said the King. “Take the frog with

you.”

The

Princess shuddered, but she dared not refuse.

She

took the frog with her up to her room, and put him down in the darkest

corner,

where she would not see him. Then she undressed and went to bed. But

scarcely

had her head touched the pillow when she heard the frog calling her.

“King’s

daughter, King’s daughter! Is this the way you keep your promise? Lift

me up to

the bed, for the floor is cold and hard.”

The

Princess sprang from the bed and seized the frog in her hands.

“Miserable

frog,” she cried, “you shall not torment me in this way.” So saying she

threw

the frog against the wall with all her force.

But no

sooner did the frog touch the wall than it turned into a handsome young

prince,

all dressed in green, with a golden crown upon his head, and a chain of

emeralds about his neck.

The

Prince came to her, and took her by the hand.

“Dear

Princess,” said he, “you have broken the enchantment that held me. A

cruel

fairy was angry with my father, and so she changed me into a frog, and

put me

there in the fountain. But now that the enchantment is broken we can

really be

playmates, and when you are old enough you shall be my wife.”

The

Princess did not say no. She was delighted at the thought of having

such a

handsome playmate. And as for marrying him later on, she was quite

willing for

that, too.

So

the Prince stayed there in the palace, and the King was very glad to

think he

was to have him for a son-in-law, and when he and the Princess were

married,

there was great rejoicing and feasting through all the kingdom.

The

Prince, however, was not willing to stay away from his own kingdom any

longer.

He said he must return to see his old father.

One

day a handsome golden coach drawn by eight white horses drove up to the

door.

It had been sent by the Prince’s father to fetch him home again. Upon

the box

rode the faithful servant who had cared for the Prince when he was a

child.

When

the Prince had been carried away by the fairy this faithful servant had

grieved

so bitterly he had feared his heart would break. To keep this from

happening he

had put three great iron bands around his body.

The

Prince and the Princess entered the coach, and away went the horses.

They had

not driven far, however, when a loud crack was heard.

“What

is that?” cried the Princess. “Surely something has broken.”

“Yes,

mistress,” answered the faithful servant,

“It

was a band that bound my heart.

My

joy hath broken it apart.”

They

drove a little farther, and then there came another crack, even louder

than the

first.

“Surely

the coach is breaking down,” cried the Prince.

“Nay,

master,” answered the faithful servant,

“’Tis

but my joy that rives apart

The

second band that held my heart.”

A

little farther on there came a crack that was louder than any.

“Now

surely something has broken,” cried the Prince and Princess together.

“’Tis

the last band that held my heart,

And

joy has riven all apart,”

answered the

servant.

After

that they drove on quietly until they reached their own country. There

the

Prince and Princess lived in happiness to the end of their lives, and

the

faithful servant with them.

THE WOLF AND THE FIVE LITTLE GOATS

There

was once a mother goat who had five little kids, and these kids were so

dear to

her that nothing could have been dearer.

One

day the mother goat was going to the forest to gather some wood for her

fire.

“Now, my little kids,” said she, “you must be very careful while I am

away. Bar

the door behind me, and open it to nobody until I return. If the wicked

wolf

should get in he would certainly eat you.”

The

little kids promised they would be careful, and then their mother

started out,

and as soon as she had gone they barred the door behind her.

Now

it so happened the old wolf was on the watch that day. He saw the

mother goat

trotting away toward the forest, and as soon as she was out of sight,

he crept

down to the house and knocked at the door — rap-tap-tap!

“Who

is there?” called the little kids within.

“It

is I, your mother, my dears,” answered the wolf in his great rough

voice. “Open

the door and let me in.”

But

the kids were very clever little kids. “No, no,” they cried. “You are

not our

mother. Our mother has a soft, sweet voice, and your voice is harsh and

rough.

You must be the wolf.”

When

the wolf heard this he was very angry. He battered and battered at the

door,

but they would not let him in. Then he turned and galloped away as fast

as he

could until he came to a dairy. There he stuck his head in at the

window, and

the woman had just finished churning her butter.

“Woman,

woman,” cried the wolf, “give me some butter. If you do not I will come

in and

upset your churn.”

The

woman was frightened. At once she gave him a great deal of butter — all

he

could eat.

The

wolf swallowed it down, and then he ran back to the goat’s house and

knocked at

the door — rat-tat-rat!

“Who

is there?” asked the little goats within.

“Your

mother, my dears,” answered the wolf, and now his voice was very soft

and

smooth because of the butter he had swallowed.

“It is

our mother,” cried the little kids, and they were about to open the

door, but

the littlest kid of all, who was a very wise little kid, stopped them.

“Wait

a bit,” said he. “It sounds like our mother’s voice, but before we open

the

door we had better be very, very sure it is not the wolf.” Then he

called

through the door, “Put your paws up on the windowsill.”

The

wolf suspected nothing. He put his paws up on the windowsill, and as

soon as

the little kids saw them they knew at once that it was not their

mother. “No, no,”

they cried, “you are not our mother. Our mother has pretty white feet,

and your

feet are as black as soot. You must be the wolf.”

When

the wolf heard this he was angrier than ever. He turned and galloped

away

again, and as he galloped he growled to himself and gnashed his teeth.

Presently

he came to a baker’s shop, and there he stuck his head in at the window.

“Baker,

baker, give me some dough,” he cried. “If you do not I will upset your

pans and

spoil your baking.”

The

baker was frightened. At once he gave the wolf all the dough he wanted.

The

wolf seized it and ran away with it. He ran until he came to the goat’s

house.

There he sat down and covered his black feet all over with the white

dough.

Then he knocked at the door — rat-tat-tat!

“Who

is there?” cried the little goats within.

“Your

mother, my dears, come home again,” answered the wolf, in his smooth

buttery

voice.

“Put

your paws up on the windowsill.”

The

wolf put his paws up on the windowsill, and they looked quite white

because of

the dough. Then the little kids felt sure it was their mother, and they

gladly

opened the door.

“Woof!”

In bounded the wicked wolf.

The

little goats cried out and away they ran, some in one direction, and

some in

another. They hid themselves one behind the door, and one in the

dough-trough,

and one in the wash-tub, and one under the bed, and one (and he was the

littlest one of all) hid in the tall clock-case. The wolf stood there

glaring

about him, and not as much as a tail of one of them could he see.

Then

he began to hunt about for them, but he had to be in a hurry, because

he was

afraid the mother goat would come home again.

He

found the kid behind the door, and he was in such a hurry he swallowed

it whole

without hurting it in the least. He found the one in the wash-tub, and

he

swallowed it whole, too. He found the one in the dough-trough, and it,

too, he

swallowed whole. He found the one under the bed and he swallowed it

whole. The

only one he did not find was the one in the clock-case, and he never

thought of

looking there. He hunted around and hunted around, and he was afraid to

stay

any longer for fear their mother would come home.

But

now the old wolf felt very heavy and sleepy. He looked around for a

place to go

in order to lie down and rest.

Not

far away were some rocks and trees that made a pleasant shadow. Here

the wolf

stretched himself out, and presently he was snoring so loudly that the

leaves

of the trees shook overhead.

Soon

after this the mother goat came home. As soon as she saw the door of

the house

standing open, she knew at once that some misfortune had happened. She

went in

and looked about her. The furniture was all upset and scattered about

the room.

“Alas, alas! My dear little kids!” cried the mother. “The wicked wolf

has

certainly been here and eaten them all.”

“He

didn’t eat me,” said a little voice in the clock-case.

The

mother goat opened the door of the clock-case and the littlest kid of

all

hopped out.

“But

why were you in the clock-case? And what has happened?” asked the

mother.

Then

the little kid told her all about how the wolf had come there with his

buttery

voice and his whitened paws, and how they had let him in, and how he

had

swallowed all four of the other little kids, so that he alone was left.

After

the mother goat had heard the story she went to the door and looked

about. Then

she heard the old wolf snoring where he lay asleep under the nut-trees

in the

shade of the rocks.

“That

must be the old wolf snoring,” said the mother goat, “and he cannot be

far

away. Do not make a noise, my little kid, but come with me.”

The

mother goat stole over to the heap of rocks, and the little kid

followed her on

tiptoes. She peeped and peered, and there lay the old wolf so fast

asleep that

nothing less than an earthquake would have wakened him.

“Now,

my little kid,” whispered the mother, “run straight home again as fast

as you

can, and fetch me my shears and a needle and some stout thread.”

This

the little kid did, and he ran so softly over the grass that not even a

mouse

could have heard him.

As

soon as he returned the mother goat crept up to the old wolf, and with

the

sharp shears she slit his hide up just as though it had been a sack.

Out popped

one little kid, and out popped another little kid, and another, and

another,

and there they all were, just as safe and sound as though they had

never been

swallowed. And all this while the old wolf never stirred nor stopped

snoring.

“And

now, my little kids,” whispered the mother, “do you each one of you

bring me a

big round stone, but be very quick and quiet, for your lives depend

upon it.”

So

the little kids ran away, and hunted around, and each fetched her back

a big

round stone, and they were very quick and quiet about it, just as their

mother

had bade them be.

The

old goat put the stones inside the wolf, where the little kids had

been, and

then she drew the hide together and sewed it up, using the stout,

strong

thread. After that she and the little kids hid themselves behind the

rocks, and

watched and waited.

Presently

the old wolf yawned and opened his eyes. Then he got up and shook

himself, and

when he did so the stones inside him rattled together so that the goat

and the

little kids could hear them, where they hid behind the rocks.

“Oh,

dear! Oh, dear me!” groaned the wolf;

“What

rattles, what rattles against my poor bones?

Not

little goats, I fear, but only big stones.”

Now

what with the stones inside of him and the hot sun overhead the wolf

grew very

thirsty. Near by was a deep well, with water almost up to the brink of

it. The

old wolf went to drink. He leaned over, and all the stones rolled up to

his

head and upset him. Plump! he went down into the water, and the stones

carried

him straight to the bottom. He could not swim at all, and so he was

drowned.

But

all the little kids ran out from behind the rocks and began to dance

around the

well.

“The

old wolf is dead, A-hey! A-hey!

The

old wolf is dead, A-hey!”

they

sang, and the mother goat came and danced with them, they were all so

delighted.

THE GOLDEN

GOOSE

There

was once an honest laborer who had three sons. The two eldest were

stout clever

lads, but as to the youngest one, John, he was little better than a

simpleton.

One

day their mother wanted some wood from the forest, and it was the

eldest lad

who was to go and get it for her. It was a long way to the forest, so

the

mother filled a wallet with food for him. There was a loaf of fine

white bread,

and a bit of cheese, and a leathern bottle of good red wine as well.

The

lad set off and walked along and walked along and after awhile he came

to the

place where he was going, and there under a tree sat an old, old man.

His

clothes were gray, and his hair was gray, and his face was gray, so he

was gray

all over.

“Good-day,”

said the man.

“Good-day,”

said the lad.

“I am

hungry,” said the gray man. “Have you not a bite and sup that you can

share

with me?”

“Food

I have, and drink too,” said the lad, “but it is for myself, and not

for you.

It would be a simple thing for me to carry it this far just to give it

to a

beggar”; and he went on his way.

But

it was bad luck the lad had that day. Scarcely had he begun chopping

wood when

the head of the ax flew off, and cut his foot so badly that he was

obliged to

go limping home, with not even so much as a fagot to carry with him.

The

next day it was the second son who said he would go to the forest for

wood.

“And

see that you are more careful than your brother,” said his mother. Then

she

gave him a loaf of bread, and a bit of cheese, and a bottle of wine,

and off he

set.

Presently

he came to the forest, and there, sitting in the same place where he

had sat

before, was the old gray man.

“Good-day,”

said the man.

“Good-day,”

said the lad.

“I am

hungry,” said the gray man. “Have you not a bite or a sup to share with

me?”

“Food

I have and drink as well, but I am not such a simpleton as to give it

away when

I need all for myself.”

The

lad went on to the place where he was going, and took his ax and began

to chop,

but scarcely had he begun when the ax slipped and cut his leg so badly

that the

blood ran, and he could scarcely get home again.

That

was a bad business, for now both of the elder brothers were lame.

The

next day the simpleton said he would go to the forest for wood.

“You,

indeed!” cried his mother. “It is not enough that your two brothers are

hurt?

Do you think you are smarter than they are? No, no; do you stay quietly

here at

home. That is the best place for you.”

But

the simpleton was determined to go, so his mother gave him an end of

dough that

was left from the baking and a bottle of sour beer, for that was good

enough

for him. With these in his wallet John started off, and after awhile he

came to

the forest, and there was the gray man sitting just as before.

“Good-day,”

said the man.

“Good-day,”

answered the simpleton.

“I am

hungry,” said the gray man. “Have you not a bite or sup that you can

share with

me?”

Oh

yes, the simpleton had both food and drink in his wallet. It was none

of the

best, but such as it was he was willing to share it.

He

reached into his wallet and pulled out the piece of dough, but what was

his

surprise to find that it was dough no longer, but a fine cake, all made

of the

whitest flour. The old man snatched the cake from John and ate it all

up in a

trice. There was not so much as a crumb of it left.

“Poor

pickings for me!” said John.

And

now the old gray man was thirsty. “What have you in that bottle?” he

asked.

“Oh,

that was only sour beer.”

The

old man took the bottle and opened it. “Sour beer! Why it is wine,” he

cried,

“and of the very best, too.”

And

the simpleton could tell it was by the smell of it. But the smell of it

was all

he got, for the old man raised the bottle to his lips, and when he put

it down

there was not a drop left in it.

“And

now I may go thirsty as well as hungry,” said John.

“Never

mind that,” said the old man. “After this you may eat and drink of the

best

whenever you will. Go on into the forest and take the first turning to

the

right. There you will see a hollow oak tree. Cut it down, and whatever

you find

inside of it you may keep; it belongs to me, and it is I who give it to

you.”

Then

of a sudden the old man was gone, and where he went the simpleton could

have

told no one.

The

lad went on into the forest, as the gray man had told him, and took the

first

turn to the left, and there sure enough was a hollow oak tree. The lad

could

tell it was hollow from the sound it made when his ax struck it.

John

set to work, and chopped so hard the splinters flew.

After

awhile he cut through it so that the tree fell, and there, sitting in

the

hollow, was a goose, with eyes like diamonds, and every feather of pure

gold.

When

John saw the goose he could not wonder enough. He took it up under his

arm and

off he set for home, for there was no more chopping for him that day.

But

if the goose shone like gold it weighed like lead. The farther John

went the

wearier he grew. After awhile he came to an inn, just outside of the

city where

the King lived. There the simpleton sat him down to rest. He pulled a

feather

from the golden goose, and gave it to the landlord and bade him bring

him food

and drink, and with such payment as that it was the very best that the

landlord

sat before him you may be sure.

While

the simpleton ate and drank the landlord’s wife and daughter watched

him from a

window.

“Oh,

if we only had a second feather,” sighed the daughter.

“Oh,

if we only had!” sighed the mother.

Then

the two agreed between them that when the simpleton had finished eating

and

drinking, the daughter should creep up behind him and pluck another

feather

from the bird.

Presently

John could eat and drink no more. He rose up and tucked the golden

goose under

his arm, and off he set.

The

landlord’s daughter was watching, and she stole up behind him and

caught hold

of a feather in the goose’s tail. No sooner had she touched it,

however, than

her fingers stuck, and she could not let go. Off marched John with the

goose

under his arm, and the girl tagging along after him.

The

mother saw her following John down the road, and first she called, and

then she

shouted, and then she ran after her and caught hold of her to bring her

home.

But no sooner had she laid hands on the girl than she, too, stuck, and

was

obliged to follow John and the golden goose.

The

landlord was looking from the window. “Wife, wife,” he cried, “where

are you

going?” And he hurried after her and caught her by the sleeve. Then he

could

not let go any more than the others.

The

simpleton marched along with the three tagging at his heels, and he

never so

much as turned his head to look over his shoulder at them.

The

road ran past a church, and there was the clergyman just coming out of

the

door. “Stop, stop!” he cried to the landlord. “Have you forgotten you

have a

christening feast to cook to-day?” And he ran after the landlord and

caught

hold of him, and then he too stuck.

The

sexton saw his master following the landlord, and he ran and caught

hold of his

coat, and he too had to follow. So it went. Everyone who touched those

who

followed the golden goose could not let go, and were obliged to tag

along at

John’s heels.

Now

the King of that country had a daughter who was so sad and doleful that

she was

never known to smile. For this reason a gloom hung over the whole

country, and

the King had promised that any one who could make the Princess laugh

should

have her as a wife and a half of the kingdom as well.

It so

chanced the simpleton’s way led him through the city and by the time he

came in

front of the King’s palace the whole street was in an uproar, and John

had a

long train of people tagging along after him.

The

Princess heard the noise in the room where she sat sighing and wiping

her eyes,

and as she was very curious she went to the window and looked out to

see what

all the uproar was about.

When

she saw the simpleton marching along with a goose under his arm and a

whole

string of people after him, all crying and bawling and calling for

help, it

seemed to her the funniest thing she had ever seen. She began to laugh,

and she

laughed and laughed. She laughed until the tears ran down her cheeks

and she

had to hold her sides for laughing.

But

it was no laughing matter for the King, as you may believe. Here was a

poor

common lad, and a simpleton at that, who had made the Princess laugh;

so now,

by all rights, he might claim her for a wife, and the half of the

kingdom, too.

The

King frowned and bit his nails, and then he sent for John to be brought

before

him, and the lad came in alone, for he had set the people free at the

gates.

“Listen,

now,” said the King to John. “It is true I promised that anyone who

made the

Princess laugh should have her for a wife, but there is more to the

matter than

that. Before I hand over part of the kingdom to anyone, I must know

what sort

of friends he has, and whether they are good fellows. If you can bring

here a

man who can drink a whole cellar full of wine at one sitting then you

shall

have the Princess and part of the kingdom, just as promised; but if you

cannot

you shall be sent home with a good drubbing to keep you quiet.”

When

John heard that he made a wry face. He did not know where he could find

a man

who could drink a whole cellar full of wine at one sitting.

He

went out from the castle, and suddenly he remembered the old gray man

who had

given him the golden goose. If the old man had helped him once perhaps

he might

again.

He

set out for the forest, and it was not long before he came to it.

There,

sitting where the old gray man had sat before, was a man with a sad and

rueful

face. He looked as though he had never smiled in all his life. He was

talking

to himself, and when the simpleton drew near he found the man was

saying over

and over, “How dry I am! How dry I am! Not even the dust of a summer’s

day is

as dry as I.”

“If

you are so thirsty, friend,” said John, “rise up and follow me. Do you

think

you could drink a whole cellar full of wine at one sitting?”

Yes,

the man could do that, and glad to get it, too. A whole cellar full of

wine

would be none too much to satisfy such a thirst as his.

“Then,

come along,” said John.

He

took the man back to the castle and down into the cellar where all the

casks of

wine were stored. When the man saw all that wine his eyes sparkled with

joy. He

sat him down to drink, and one after another he drained the casks until

the

very last one of them was empty. Then he stretched himself and sighed.

“Now I

am content,” said he.

As

for the King his eyes bulged with wonder that any one man could drink

so much

at one sitting.

“Yes,

that is all very well,” said he to the simpleton. “I see you have a

friend who

can drink. Have you also a friend who can eat a whole mountain of bread

without

stopping? If you have, you may claim the Princess for your wife, but if

you

have not, then you shall be sent home with a good drubbing.”

Well,

that was not in the bargain, but perhaps the simpleton might be able to

find

such a man.

He

set off for the forest once more, and when he came near the place where

the

thirsty man had sat he saw there another man, and he was enough like

the

thirsty man to be his brother.

As

John came near to where he sat he heard him talking to himself, and

what he was

saying over-and-over was, “How hungry I am. Oh, how hungry I am.”

“Friend,”

said the simpleton, “are you hungry enough to eat a whole mountain of

bread? If

you are I may satisfy you.”

Yes,

a whole mountain of bread would be none too much for the hungry man.

So

John bade the stranger follow him and then he led the way back to the

castle.

There

all the flour in the kingdom had been gathered together into one great

enormous

mountain of dough. When John saw how big it was his heart failed him.

“Can

you eat that much?” he asked of the hungry man.

“Oh,

yes, I can eat that much, and more, too, if need be,” said the man.

Then

he sat down before the mountain of bread and began to eat. He ate and

he ate,

and he ate, and when he finished not so much as a crumb of bread was

left.

As

for the King he was a sad and sorry man. Not only was his daughter and

part of

the kingdom promised to a simpleton, but he had not even a cupful of

flour left

in the palace for his breakfast.

And

still the King was not ready to keep the promises he had made. There

was one

thing more required of the simpleton before he could have the Princess

and part

of the kingdom for himself. Let him bring to the King a ship that would

sail

both on land and water, and he should at once marry the Princess, and

no more

words about it.

Well,

John did not know about that, but he would do the best he could. He

took the

road that led back to the forest, and when he reached the place where

the old

man had sat, there was the old man sitting again just as though he had

never

moved from that one spot.

“Well,”

said the old man, “and has the golden goose made your fortune?”

“That,”

answered John, “is as it may be. It may be I am to have the half of a

kingdom

and a princess for a wife, and it may be that I am only to get a good

drubbing.

Before I win the Princess I must find a ship that will sail on land as

well as

on water, and if there is such a thing as that in the world I have

never heard

of it.”

“Well,

there might be harder things than that to find,” said the old man. It

might be

he could help John out of that ditch, and what was more he would, too,

and all

that because John had once been kind to him. The old man then reached

in under

his coat and brought out the prettiest little model of a ship that ever

was

seen. Its sails were of silk, its hull of silver, and its masts of

beaten gold.

The

old man set the ship on the ground, and at once it began to grow. It

grew and

grew and grew, until it was so large that it could have carried a score

of men

if need be.

“Look,”

said the old man. “This I give to you because you were kind to me and

willing

to share the best you had. Moreover it was I who drank the wine and ate

the

mountain of bread for you. Enter into the ship and it will carry you

over land

and water, and back to the King’s castle. And when he sees this ship he

will no

longer dare to refuse you the Princess for your wife.”

And

so it was. John stepped into the ship and sailed away until he came to

the

King’s palace, and when the King saw the ship he was so delighted with

it that

he was quite willing to give the Princess to the simpleton for a bride.

The

marriage was held with much feasting and rejoicing, and John’s father

and

mother and his two brothers were invited to the feast. But they no

longer

called him the simpleton; instead he was His Majesty, the wise King

John.

As

for the old gray man he was never seen again, and as the golden goose

had

disappeared also, perhaps he flew away on it.

THE

THREE SPINNERS

There

was once a girl who was so idle and lazy that she would do nothing but

sit in the

sunshine all day. She would not bake, she would not brew, she would not

spin,

she would not sew. One morning her mother lost patience with her

entirely, and

gave her a good beating. The girl cried out until she could be heard

even into

the street.

Now it

so chanced the queen of the country was driving by at that time, and

she heard

the cries. She wished to find out what the trouble was, so she stopped

her

coach and entered the house. She went through one room after another,

and

presently she came to where the girl and her mother were.

“What

is all this noise?” she asked. “Why is your daughter crying out?”

The

mother was ashamed to confess what a lazy girl she had for a daughter,

so she

told the queen what was not true.

“Oh,

your majesty,” cried she, “this girl is the worry of my life. She will

do

nothing but spin all day, and I have spent all my money buying flax for

her.

This morning she asked me for more, but I have no money left to buy it.

It was

because of that she began to cry, as you heard.”

The

Queen was very much surprised. “This girl of yours must be a very fine

spinner,” she said. “You must bring her to the palace, for there is

nothing I

love better than spinning. Bring her to-morrow, and if she is as

wonderful a

spinner as I suspect, she shall be to me as my own daughter, and shall

have my

eldest son as a husband.”

When

the girl heard she was to go to the palace and spin she was terrified.

She had

never spun a thread in her life, and she feared that when the Queen

found this

out she would be angry and would have her punished. However, she dared

say

nothing.

The

next day she and her mother went to the palace, and the Queen received

them

kindly. The mother was sent home again, but the daughter was taken to a

tower

where there were three great rooms all filled with flax.

“See,”

said the Queen. “Here is enough flax to satisfy you for awhile at

least. When

you have spun this you shall marry my son, and after that you shall

have all

the flax you want. Now you may begin, and to-morrow I will come to see

how much

you have done.”

So

saying the Queen went away, closing the door behind her.

No

sooner was the girl alone than she burst into tears. Not if she lived a

hundred

years could she spin all that flax. She sat and cried and cried and

cried.

The

next morning the Queen came back to see how much she had done. She was

very

much surprised to find the flax untouched, and the girl sitting there

with idle

hands. “How is this?” she asked. “Why are you not at your spinning?”

The

girl began to make excuses. “I was so sad at being parted from my

mother that I

could do nothing but sit and weep.”

“I

see you have a tender heart,” said the Queen. “But to-morrow you must

begin to

work. When I come again I shall expect to see a whole roomful done.”

After

she had gone the girl began to weep again. She did not know what was to

become

of her.

Suddenly

the door opened, and three ugly old women slipped into the room. The

first had

a splayfoot. The second had a lip that hung down on her chin. The third

had a

hideous broad thumb.

The

girl looked at them with fear and wonder. “Who are you?” she asked.

The

one with the splayfoot answered. “We are three spinners. We know why

you are weeping,

and we have come to help you, but before we help you, you must promise

us one

thing: that is that when you are married to the Prince, we may come to

your

wedding feast, that you will let us sit at your table, and that you

will call

us your aunts.”

“Yes,

yes; I will, I will,” cried the girl. She was ready to promise anything

if they

would only help her.

At

once the splayfoot sat down at the wheel, and began to spin and tread.

She with

the hanging lip moistened the thread, and the woman with the broad

thumb

pressed and twisted it. They worked so fast that the thread flowed on

like a

swift stream. Before the next evening they had finished the whole

roomful of

flax.

When

the Queen came again she was delighted to find so much done.

“To-morrow,” said

she, “you shall begin in the second room.”

The

next day the girl was taken into the second room, and it was larger

than the

first and was also full of flax.

Scarcely

had the Queen left her when the door was pushed open, and the three old

women

came into the room.

“Remember

your promise,” said they.

“I

remember,” answered the girl.

The

old women then took their places and began to spin. Before the next

evening

they had finished all the flax that was in the room.

When

the Queen came to look at what had been done, she was filled with

wonder. Not

only had all the flax in the room been spun, but she had never seen

such smooth

and even threads.

“To-morrow,”

said she, “you shall spin the flax that is in the third room, and the

day after

you shall be married to my son.”

The

third day all happened just as it had before. The girl was taken to the

third

room and it was even larger than the others. Scarcely had she been left

alone

when the three old women opened the door and came in.

“Remember

your promise,” said they.

“I

will remember,” answered the girl.

The

old women took their places, and before night all the flax was spun.

Then they

rose. “To-morrow will be your wedding day, and we will be at the feast.

If you

keep your word to us, all will go well with you, but if you forget it,

misfortune will surely come upon you.” Then they disappeared through

the door

as they had come, the eldest first.

When

the Queen came that evening she was even more delighted than before.

Never had

she seen such thread, so smooth it was and even.

The

girl was led down from the tower and dressed in silks and velvets and

jewels,

and when thus dressed she was so beautiful that the Prince was filled

with love

and joy at the sight of her. The next day they were married, and a

grand feast

was spread. To this feast all the noblest in the land were invited.

The

bride sat beside her husband, and he could look at no one else, she was

so

beautiful.

Just

as the feast was about to begin the door opened and the three old women

who had

spun the flax came in.

The

Prince looked at them wonderingly. Never had he seen such hideous, ugly

creatures before. “Who are these?” he asked of the girl.

“These,”

said she, “are my three old aunts, and I have promised they shall sit

at the

table with us, for they have been so kind to me that no one could be

kinder.”

The

girl then rose, and went to meet the old women. “Welcome, my aunts,”

she said,

and led them to the table. The Prince loved the girl so dearly that all

she did

seemed right to him. He commanded that places should be put for the old

women,

and they sat at the table with him and his bride.

They

were so hideous, however, that the Prince could not keep his eyes off

them. At

length he said to the eldest, “Forgive me, good mother, but why is your

foot so

broad?”

“From

treading the thread, my son, from treading the thread,” she answered.

The

Prince wondered; he turned to the second old woman. “And you, good

mother,” he

said, “why does your lip hang down?”

“From

wetting the thread,” she answered. “From wetting the thread.”

The

Prince was frightened. He spoke to the third old woman. “And you, why

is your

thumb so broad, if I may ask it?”

“From

pressing and twisting,” she answered. “From pressing and twisting.”

The

Prince turned pale. “If this is what comes of spinning,” said he,

“never shall

my bride touch the flax again.”

And

so it was. Never was the girl allowed even to look at a spinning wheel

again;

and that did not trouble her, as you may guess.

As

for the old women, they disappeared as soon as the feast was over, and

no one

saw them again, but the bride lived happy forever after.

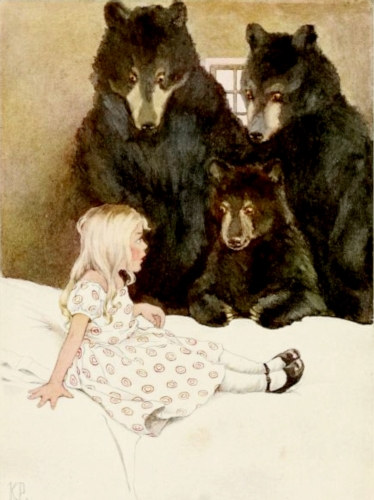

GOLDILOCKS

AND THE THREE BEARS

There

was once a little girl whose hair was so bright and yellow that it

glittered in

the sun like spun-gold. For this reason she was called Goldilocks.

One

day Goldilocks went out into the meadows to gather flowers. She

wandered on and

on, and after a while she came to a forest, where she had never been

before.

She went on into the forest, and it was very cool and shady.

Presently

she came to a little house, standing all alone in the forest, and as

she was

tired and thirsty she knocked at the door. She hoped the good people

inside

would give her a drink, and let her rest a little while.

Now,

though Goldilocks did not know it, this house belonged to three bears.

There

was a GREAT BIG FATHER BEAR, and a middling-sized mother bear, and a dear

little baby bear, no bigger than Goldilocks herself. But the three

bears

had gone out to take a walk in the forest while their supper was

cooling, so

when Goldilocks knocked at the door no one answered her.

She

waited awhile and then she knocked again, and as still nobody answered

her she

pushed the door open and stepped inside. There in a row stood three

chairs. One

was a GREAT BIG CHAIR, and it belonged to the father bear. And one was

a

middling-sized chair, and it belonged to the mother bear, and one was a

dear

little chair, and it belonged to the baby bear. And on the table

stood

three bowls of smoking hot porridge. “And so,” thought Goldilocks, “the

people

must be coming back soon to eat it.”

She

thought she would sit down and rest until they came, so first she sat

down in

the GREAT BIG CHAIR, but the cushion was too soft. It seemed as though

it would

swallow her up. Then she sat down in the middle-sized chair, and the

cushion

was too hard, and it was not comfortable. Then she sat down in the dear

little chair, and it was just right, and fitted her as though it

had been

made for her. So there she sat, and she rocked and she rocked, and she

sat and

she sat, until with her rocking and her sitting she sat the bottom

right out of

it.

And

still nobody had come, and there stood the bowls of porridge on the

table.

“They can’t be very hungry people,” thought Goldilocks to herself, “or

they

would come home to eat their suppers.” And she went over to the table

just to

see whether the bowls were full.

The

first bowl was a GREAT BIG BOWL with a GREAT BIG WOODEN SPOON in it,

and that

was the father bear’s bowl. The second bowl was a middle-sized bowl,

with a

middle-sized wooden spoon in it, and that was the mother bear’s bowl.

And the

third bowl was a dear little bowl, with a dear little

silver spoon

in it, and that was the baby bear’s bowl.

The

porridge that was in the bowls smelled so very good that Goldilocks

thought she

would just taste it.

She

took up the GREAT BIG SPOON, and tasted the porridge in the GREAT BIG

BOWL, but

it was too hot. Then she took up the middle-sized spoon and tasted the

porridge

in the middle-sized bowl, and it was too cold. Then she took up the little

silver spoon and tasted the porridge in the dear little bowl,

and it

was just right, and it tasted so good that she tasted and tasted, and

tasted

and tasted until she tasted it all up.

After

that she felt very sleepy, so she went upstairs and looked about her,

and there

were three beds all in a row. The first bed was the GREAT BIG BED that

belonged

to the father bear. And the second bed was a middling-sized bed that

belonged

to the mother bear, and the third bed was a dear little bed

that

belonged to the dear little baby bear.

Goldilocks

lay down on the GREAT BIG BED to try it, but the pillow was too high,

and she

wasn’t comfortable at all.

Then

she lay down on the middle-sized bed, and the pillow was too low, and

that wasn’t

comfortable either.

Then

she lay down on the little baby bear’s bed and it was exactly

right, and

so very comfortable that she lay there and lay there until she went

fast

asleep.

Now

while Goldilocks was still asleep in the little bed the three bears

came home

again, and as soon as they stepped inside the door and looked about

them they

knew that somebody had been there.

“SOMEBODY’S

BEEN SITTING IN MY CHAIR,” growled the father bear in his great big

voice, “AND

LEFT THE CUSHION CROOKED.”

“And

somebody’s been sitting in my chair,” said the mother bear, “and left

it

standing crooked.”

“And

somebody’s been sitting in my chair,” squeaked the baby bear, in

his shrill

little voice, “and they’ve sat and sat till they’ve sat the bottom

out”;

and he felt very sad about it.

Then

the three bears went over to the table to get their porridge.

“WHAT’S

THIS!” growled the father bear, in his great big voice, “SOMEBODY’S

BEEN

TASTING MY PORRIDGE, AND LEFT THE SPOON ON THE TABLE.”

“And

somebody’s been taking my porridge,” said the mother bear in her

middle-sized

voice, “and they’ve splashed it over the side.”

“And

somebody’s been tasting my porridge,” squealed the baby bear, “and

they’ve tasted and tasted until they’ve tasted it all up.” And when

he said

so the baby bear looked as if he were about to cry.

“If

somebody’s been here they must be here still,” said the mother bear; so

the

three bears went upstairs to look.

First

the father bear looked at his bed. “SOMEBODY’S BEEN LYING ON MY BED AND

PULLED

THE COVERS DOWN,” he growled in his great big voice.

Then

the mother bear looked at her bed. “Somebody’s been lying on my bed and

pulled

the pillow off,” said she in her middle-sized voice.

Then

the baby bear looked at his bed, and there lay little Goldilocks with

her

cheeks as pink as roses, and her golden hair all spread over the pillow.

“Somebody’s

been lying in my bed,” squeaked the baby bear joyfully, “and

here she is

still!”

Now

when Goldilocks in her dreams heard the great big father bear’s voice

she

dreamed it was the thunder rolling through the heavens.

And

when she heard the mother bear’s middle-sized voice she dreamed it was

the wind

blowing through the trees.

But

when she heard the baby bear’s voice it was so shrill and sharp that it

woke

her right up. She sat up in bed and there were the three bears standing

around

and looking at her.

“Oh,

my goodness me!” cried Goldilocks. She tumbled out of bed and ran to

the

window. It was open, and out she jumped before the bears could stop

her. Then

home she ran as fast as she could, and she never went near the forest

again.

But the little baby bear cried and cried because he had wanted the

pretty

little girl to play with.

THE

THREE LITTLE PIGS

A

mother pig and her three little pigs lived together in a wood very

happily all

through the long summertime, but towards autumn the mother pig called

her

little ones to her and said, “My dear little pigs, the time has come

for you to

go out into the world and seek your own fortunes. You will each want to

build a

little house to live in, but do not build them of straw or leaves;

straws are

brittle and leaves are frail. Build your houses of bricks, for then you

will

always have a safe place to live in; you can go in and lock the door,

and

nothing can harm you.” She then bade the little pigs farewell, and away

they

ran out into the world to make their fortunes.

The

first little pig had not gone far when he met a man with a load of

straw. The

straw looked so warm, and smelled so good that the little pig quite

forgot what

his mother had told him.

“Please,

Mr. Man,” said the little pig, “give me enough straw to build a house

to keep

me warm through the long winter.”

The

man did not say no. He gave the little pig all the straw he wanted, and

then he

drove on.

The

little pig built himself a house of straw, and it was so warm and cosy

that he

was quite delighted with it. “How much better,” said he “than a house

of cold

hard bricks.”

So he

lay there snug and warm, and presently the old wolf knocked at the door.

“Piggy-wig,

piggy-wig, let me in!” he cried.

“I

won’t, by the hair on my chinny-chin-chin,” answered the pig.

“Then

I’ll huff, and I’ll puff, and I’ll blow your house in.”

The

little pig laughed aloud, for he felt very safe in his snug straw house.

“Well,

then huff, and then puff, and then blow my house in!” he cried.

Well,

the old wolf did huff and puff, and he did blow the

house in, for

it was only made of straw, and then he ate up the pig.

The second

little pig when he left the forest ran along and ran along and

presently he met

a man with a great load of leaves.

“Oh,

kind Mr. Man, please give me some leaves to build me a little house for

the

winter time,” cried the piggy.

The

man was willing to do this. He gave the pig all the leaves he wanted,

and then

he went on his way.

The

pig built himself a house of leaves and it was even snugger and warmer

than the

straw house had been. “How silly my mother was,” said the pig, “to tell

me to

build a brick house. What could be warmer and cosier and safer than

this.” And

he snuggled down among the leaves and was very happy.

Presently

along came the great wolf, and he stopped and knocked at the door.

“Piggy-wig,

piggy-wig, let me in!” he cried.

“I

won’t, by the hair of my chinny-chin-chin!”

“Then

I’ll huff, and I’ll puff, and I’ll blow your house in.”

The

little pig laughed when he heard that, for the walls were thick, and he

felt

secure.

“Well,

then huff, and then puff, and then blow my house in.”

So

the wolf huffed, and he puffed, and he did blow the house in,

and he ate

up the little pig that was inside of it.

Now

the third little pig was the smallest pig of all, but he was a very

wise little

pig, and he meant to do exactly as his mother had told him to do. After

he left

the forest he met a man driving a wagon-load of straw, but he did not

ask for

any of it. He met the man with the load of leaves, but he did not ask

for any

of it. He met a man with a load of bricks, and then he stopped

and

begged so prettily for enough bricks to build himself a little house

that the

man could not refuse him.

The

pig took the bricks and built himself a little red house with them, and

it was

not an easy task either. When it was done it was not so soft as the

little

straw house, and it was not so warm as the little leaf house, but it

was a very

safe little house.

Presently

the old wolf came along and knocked at the door — rat-tat-tat!

“Piggy-wig,

piggy-wig, let me in,” he called.

“I

won’t, by the hair on my chinny-chin-chin.”

“Then

I’ll huff, and I’ll puff, and I’ll blow your house in.”

“Well,

then huff, and then puff, and then blow my house in,” answered the pig.

So

the old wolf huffed and he puffed, and he puffed and he huffed,

and he

HUFFED AND HE PUFFED till he almost split his sides, and he just couldn’t

blow the house in, and the little pig laughed to himself as he sat safe

and comfortable

inside there.

The

old wolf saw there was nothing to be done by blowing, so he sat down

and

thought and thought. Then he said, “Piggy-wig, I know where there is a

field of

fine turnips.”

“Where?”

asked the little pig.

“Open

the door and I will tell you.”

No,

the little pig could hear quite well with the door closed.

“It

is just up the road three fields away,” said the wolf, “and if you

would like

to have some I will come for you at six o’clock to-morrow morning, and

we will

go and dig them up together.”

“At

six o’clock!” said the little pig. “Very well.”

Then

the old wolf trotted off home, licking his lips, and he was well

content, for

he thought he would have pig for breakfast the next day.

But

the next morning the little pig was up and astir by five o’clock. Off

he

trotted to the turnip field and gathered a whole bagful of turnips and

was home

again before the old wolf thought of coming.

At

six o’clock the old wolf knocked at the door.

“Are

you ready to go for the turnips, Piggy?” he cried.

“Ready!”

answered the pig. “Why I was up and off to the field an hour ago and I

have all

the turnips I want, and I’m boiling them for breakfast.”

“That’s

what you did!” said the wolf. And then he thought a bit. “Piggy, do you

like

fine ripe apples?” he asked.

Yes,

the pig was very fond of apples.

“Then

I can tell you where to find some.”

“Where

is that?”

“Over

beyond the hill in the squire’s orchard, and if you will play me no

tricks I

will come for you at five o’clock to-morrow, and we will go together,

and

gather some.”

Very

well; the pig would be ready.

So

the wolf trotted off home, and this time he was very sure that he would

have a

nice fat little piggy for breakfast the next morning.

The

little pig got up at four o’clock the next day, and off he started for

the

orchard as fast as his four little feet would carry him. But the way

was long,

and the tree was hard to climb, and while he was still up among the

branches

gathering apples the old wolf came trotting into the orchard. The

little pig

was very much frightened, but he kept very still and hoped, up among

the

leaves, the wolf would not see him.

The

wolf peered about, first up one tree and then up another, and finally

he spied

the piggy up among the branches.

“Why

did you not wait for me?”

“Oh,

I knew you would be along presently.”

“How

soon are you coming down?”

“When

I have picked a few more apples.”

The

old wolf sat down at the foot of the tree, and the pig sat up among the

branches crunching apples and smacking his lips.

“Are

they good?” asked the wolf looking up; and his mouth watered.

Yes,

they were very good.

“Could

you not throw one down to me?”

Yes,

the little pig could do that.

He

picked the biggest, reddest apple he could, and then he threw it, but

he threw

it far off, and in such a way that it went bounding and rolling down

the hill

slope. The wolf bounded down the hill after it, and while he was

catching it,

the little pig climbed down the tree and ran safely home with his

basketful of

apples.

When

the old wolf found the pig had tricked him again he was very angry. He

was more

determined than ever that he would catch the little pig. He trotted off

to the

little red house and knocked at the door.

“Did

you get all the apples you wanted?” asked the wolf.

Yes,

the little pig had all he wanted, and he was very much obliged to the

wolf for

telling him about the orchard.

“Listen,

Piggy, there’s to be a fine fair over in the town to-morrow,” said the

wolf.

“Wouldn’t you like to go?”

Yes,

the little pig would like very much to go.

“Very

well,” said the wolf. “Then I will come for you at half-past three

to-morrow,

and we will go together.”

“Very

well,” said the little pig. But long before half-past three the next

day, piggy

was off to the fair, and he took four bright silver pieces with him,

for he

wanted to buy himself a butter-churn. It did not take him long to buy

the

churn, and then he started home again, carrying it on his back.

But

the wolf had learned a thing or two about the little pig’s tricks. He,

too,

started off to the fair long before half-past three, and so it was that

the

little pig was scarcely half-way home, and had just reached the top of

a high

hill, when he saw the wolf come trotting up the hill directly toward

him. The

little pig was terrified. He looked all around but he could not see any

place

to hide. He decided the best thing he could do was to get inside the

churn. So

he put it down and crept inside it. But the hill was very steep, and no

sooner

was the piggy inside the churn than it began to roll down the hill

slope bumpety-bumpety-bump,

over rocks and stones, leaping and bounding like a live thing. The

little pig

did not know what was happening to him. He began to squeal at the top

of his

voice.

The

old wolf was half-way up the hill when he heard the noise. He looked

up, and

there was a great round thing coming bounding over the rocks straight

at him,

and squeaking and squeaking as it came. He gave one look and his hair

bristled

with fear, and with a howl he turned tail and ran home as fast as he

could. He

never stopped till he was safe inside his house, and had shut and

locked the

door behind him. There he crouched, trembling and wondering what would

happen.

But nothing happened, and all was quiet, so after awhile the wolf

ventured out

and ran over to the pig’s house.

“Piggy,

Piggy! Are you in there?”

Yes,

the little pig was sitting by the fire roasting apples.

“Then,

listen while I tell you what happened to me on the way to the fair.”

Then the

wolf put his nose close to the crack of the door, and told the little

pig all

about the great round squealing thing that had chased him down the hill.

The

little pig laughed and laughed. “And I can tell you exactly what the

great

squealing thing was; it was a churn I had bought at the fair, and I was

inside

it.”

When the

old wolf heard this he was so furious that he determined to have the

little pig

whether or no, even if he had to climb up on the roof and down the

chimney to

get him. He stuck his sharp nails in between the bricks of the house

and

climbed right up the side of it and onto the roof. Then he climbed up

on the

chimney and slid down it into the fire-place.

But

the little pig had heard what he was doing, and was ready for him. He

had a great

pot of boiling water on the fire, and when he heard the wolf slipping

and

scrabbling down the chimney he took the lid off the kettle, and plump!

the old