|

1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

CHAPTER V.

A VISIT TO POPOCATEPETL

THE next day Juanita and her friends had to return to school. This was rather irksome to some of them after the holiday, but it did not take them long to get back into the routine of school life.

Juanita was the more willing to apply herself closely to her studies, for her father had promised her that on Carmen Day, if she got on well with lessons meanwhile, he would take her mother and her on a trip to Amecameca and Mt. Popocatepetl.

This was an excursion they had all longed to take for a good while, but of course Juanita was especially enthusiastic over the prospect. She was bound that it should be no fault of hers if there were any failure in the plans. So her teacher was really surprised at the attention she bestowed on her lessons.

Holidays are frequent in Mexico, and before Carmen Day, which falls on February 17th, Candlemas Day was celebrated.

In the United States the day is profanely confounded with Ground Hog. Day, but in Mexico no such custom prevails. It is known as a double-cross festival and occurs forty days after Christmas.

Commencing two days before, candles are placed at the altars of the Virgin and kept burning constantly before the pictures, big. and little, of that highly honoured woman. In the churches processions with lighted candles march back and forth, and all candles needed for the churches for the ensuing year are blessed; hence the name Candlemas Day.

But Carmen Day arrived at last, though to Juanita some of the days lagged dreadfully.

The holiday is observed as the festival of Our Lady of Carmen, especially in the Carmen District of the city. It is the saint’s day of the wife of President Diaz, who receives gifts and visits and beautiful flowers.

Juanita awoke bright and early. She needed no one to call her this morning.

Quickly she hopped out of bed and ran to her window to have a look at the sky. Clear as crystal and blue as blue could be, with the morning sun casting its radiant beams over the city with a glory and beauty exceeded nowhere. Mexico’s clear atmosphere and blue sky are rivalled only in Italy. Consequently Mexico is sometimes called the Italy of America.

In a very few moments—much quicker than usual — Juanita was dressed, and promptly at breakfast-time she appeared in the dining-room, where her mamma and papa had just preceded her. She could hardly stop to give them the usual morning greeting before she said:

“Papa, are we surely going to Amecameca to-day ?“

“We certainly are,” was the answer, “If the train goes.”

Juanita did not need her mother’s injunction not to loiter over her breakfast. Of necessity they all ate rapidly — perhaps too rapidly, for shortly before seven o’clock the maid told them that the carriage which was to convey them to the railway station was at the door.

Ordinarily they would have taken the streetcars, but as the street-car service in the city was rather unreliable, they did not dare to trust to it when after an early train.

Quickly donning their outer garments, Juanita and her parents got into the carriage, which drove off rapidly to the railway station. Here they arrived just in time to catch the 7.10 train for Amecameca.

It was a comparatively new experience for Juanita to ride upon a railway train. Only a few times had she been out short distances with her father or mother.

So every changing scene was a revelation to her, and as the train sped on through Ayotla and Santa Barbara she saw much to interest her, and she kept her parents busy answering the questions she asked them.

As they got farther into the country, the green fields afforded a beautiful and refreshing sight. In some places, though, there were long stretches of barren soil which bore nothing but different varieties of the cactus. Among them the century plant, or American aloe, was often seen. Its bluish-green leaves were long, with prickly edges, and there were immense clusters of yellowish flowers. The branches were sometimes forty feet high.

Again, Juanita would see the great maguey plantations, from which plant is made pulque, the national drink of Mexico. She already knew that pulque-drinking was a terrible curse to the country, and she learned from her father that if its sale were prohibited it would mean the ruin of thousands of owners of these maguey plantations. At least, that was what they said; but, even if it were true, the poorer classes of the people would be incalculably benefited, as they spend $20,000 a day on the liquor.

But the train kept steadily on. La Compañia was passed, and Temamatla in its turn. Then Tenango and Tepopula were left behind. Finally, at quarter-past nine, the trainman shouted “Amecameca,” and without delay Juanita and her parents left the cars.

They were immediately surrounded by a crowd of donkey-boys, who besought the privilege of acting as guide.

Beckoning to one of the brightest appearing lads, Señor Jiminez placed in his hand a silver coin and told him that he wanted three donkeys, — one for the señora, one for the señorita, and one for himself to ride.

With a broad smile and flourishing bow young Juan said:

“You shall have them at once, your Excellency.”

He went at once to a near-by shed, and in less time than it takes to tell it returned with the desired animals all saddled and bridled for his party.

“Now we want you to lead us by the best way to Mt. Popocatepetl,” said Señor Jiminez. “Of course we do not expect to ascend it to-day, for we have not made preparations for that; neither have we the time.”

“Yes, señor, I understand,” said Juan. “I show many people the way. I take you where you get the grand view. Then you ride across the valley to the low hills, where you find a resting-place and get some dinner. Yes, señor, I know.” And again Juan doffed his broad-brimmed hat and showed a long, even row of white teeth in his inimitable smile.

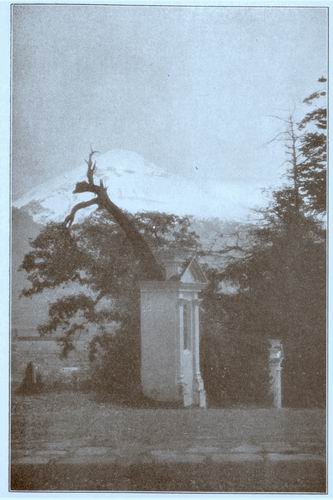

“THE WONDERFUL

VISION OF THE VOLCANO POPOCATEPETL”

So, after all were safely mounted on the little but sturdy beasts, they passed on away from the little cluster of houses that surrounded the station.

They had gone but a little way, when, as they turned a corner, the wonderful vision of the volcano Popocatepetl burst upon their sight.

At once they halted, and in silence they gazed upon it. It was too grand, too awe-inspiring, for any words. Even to Señor and Señora Jiminez, who had seen the mountain many times before, it was an entrancing view — one of those sights which, though old, is ever new.

It was a picture that would ever haunt the memory.

Against the foreground were the pin and needle branches of the pines and cedars of Amecameca, the latter brought as saplings from the forests of Lebanon centuries ago by the Spanish conquerors, and which now are large trees. In the centre of this wonderful picture, like a flattened mosaic, was the tiled town of Amecameca, while fixed against the horizon was the cold white brow of the volcano with its crown of snow, a crown sent down from heaven.

Between the town and mountain stretched before them a wide valley, fertile, and dotted with numerous haciendas. Beyond, and beneath the great peak, stood the foot-hills, sparsely inhabited and affording a poor living to those who dwelt among them.

Señor Jiminez explained to his daughter that the mountain was over three miles above the level of the sea, and that the crater, which was three miles in circumference, was over one thousand feet in depth. After gazing on the wonderful sight for a long time, the señor ordered the donkey-boy to lead on, and they took up their march across the valley to the foot-hills.

There was little conversation on the way, so majestic was the view constantly before them. They rode on and on over the winding, dusty roads until our friends had inward feelings that it must be dinner-time.

“When are we to get our dinner, papa?” asked Juanita.

“That’s what I have been wondering, too,” said mamma.

“I was just thinking it was time to find out,” said Señor Jiminez. “Juan, when are we to get that dinner you promised us?”

“Very soon, señor. Just after we get over this hill,” was the smiling response.

And sure enough, as the donkeys passed over the crown of the hill there came into sight an adobe hut of moderate size, surrounded by the low green shrubbery of the locality.

As they halted before the hut, there appeared on the scene an Indian woman and a whole swarm of scantily clad children. These Juan proudly introduced as his mother and brothers and sisters. His father, he said, was at work on a plantation down in the valley. They were all as proud of their Aztec origin as Juanita was of her Castilian forefathers.

Though all the children of this family seemed happy and contented, as Juanita’s father told her afterward, life among the Indian babies is not always smooth. They are survivors of a race long relegated to the past, and yet they carry with them all the pathos and the dignity that surrounded the best of them.

The Indian babies are the most pathetic things in the world. Although reflecting life, they seem like bundles of dead matter, So quiet are they in their misery. In Mexico, as soon as possible after birth, the Indian baby is rolled in a zarape or blanket, and the load is carried on the back of the plodding mother as she comes into the capital with her vegetables and flowers,, while the father trudges ahead with his own load. This baby cries little or none, and simply seems to vegetate. But as he is free from the restraint of extra clothing he toughens from day to day like a little animal, and, as a rule, the Mexican babies are well formed and healthy.

As he grows up life is never serious to him. As a boy the baby follows his father’s trade and the girl’s thought follows the slowly unfolding and uneventful life of the mother.

“Mother,” said Juan, “the señor and his family are very hungry. It is a long time since they had breakfast, and they have come on a long journey, — all the way from the great city. Can you give them a dinner?”

“Why, certainly, if they are willing to put up with what I can give them,” was the reply.

“We are hungry enough to eat almost anything,” said Señora Jiminez.

“Oh, mother, this is like a regular picnic, to come out here and have dinner, isn’t it?” said Juanita.

“Indeed it is, only better, for we have not got to bother with preparing the lunch,” was the reply.

Meanwhile, all had alighted from their donkeys, which Juan led away and tethered where they could get generous forage.

At the same time the Indian mother set about preparing the meal for her guests.

The visitors seated themselves upon the ground in front of the hut. In a few moments Juan returned and proceeded to set up on two benches a rough table of boards which were lying about.

Before very long the rude table was set with such viands as the Indian woman was able to produce, and the Jiminez family invited to partake. It was a very different sort of meal from their usual ones at home, but hunger is a splendid appetizer, and they ate with a relish the frijoles and tortillas.

Tortillas are similar to the unleavened bread of the East. They are made from corn put into lime-water and boiled half an hour. The husks are then removed and the ears washed with cold water. The corn is ground by hand on a stone metate, and the dough broken into pieces is formed into round cakes about six inches in diameter and one-eighth of an inch thick.

Juanita would have been much interested if she could have seen Juan’s mother and older sister slowly and laboriously grinding the corn.

The tortilla is toasted until it is brown, and it is as necessary to Mexican tables as bread to the American. The Mexicans take up their spicy dishes with the tortilla, using it as a spoon, and finally they eat the spoon!

When prepared according to the Mexican method frijoles are very palatable, and rich and poor eat these brown beans with gusto. The principal varieties of frijoles are the valle gorda and the valle chica.

The beans are put into a pot and covered with water, and boiled four hours, more water being constantly added. They are then fried in lard and eaten with their own gravy, or mashed and fried with onions.

Corn is the staff of life for these Mexican Indians, and is served in many forms, often highly seasoned with the chili. Of the three kinds of tamales the best are those prepared with chili. Some were served for Juanita and her parents. The corn is ground very fine; the dough is prepared in one vessel and the meat in another, the latter being seasoned.

Fresh corn husks are used. These are washed clean and the inside lined with the dough. Finely minced meat is placed inside, and the husks rolled like a big cigarette. They are then boiled an hour and eaten hot.

All the while our friends were feasting their bodies they were also feasting their eyes upon the majestic Popocatepetl, which towered above them in all its snowy, glittering grandeur. They could not help thinking how terrible would be the result if suddenly from its crater should belch forth the fires so long extinct.

It was no unknown thing for Mexican volcanoes to do just that thing. Señor Jiminez told how, in the middle of the eighteenth century, the site of the volcano Jorullo was covered with fields of cotton, indigo, sugar-cane, all made fertile by generous irrigation. Suddenly, without warning, the mountain cast forth a stream of lava and fire, laying waste the land, and changing the beautiful green landscape to a burning, desolate wilderness. Thousands of dollars’ worth of property were destroyed and many lives lost in the catastrophe.

This was rather a depressing story, and Juanita was a little nervous after hearing it, but her spirits were soon restored as she watched the antics and games of the little Indian children as they played about the hut.

The meal ended, Señor Jiminez gave Juan’s mother generous payment. Then he said to his wife and daughter, with a glance at the declining sun, “We must now be starting for home. The train leaves Amecameca at about quarter of five, and if we go now we can make it without hurrying the donkeys.”

Juan overheard the remark and took the hint without further orders. He soon brought up the donkeys, who also were rested and refreshed by their noonday meal.

At once the travellers mounted and took up their line of march back over the morning’s trail, down the hills into the valley, and up again into the town of Amecameca. Here they arrived in ample time for their train, which rapidly whirled them once more to their beautiful City of Mexico. At seven o’clock they were home again and eager for the supper which the cook had ready upon the table.

Though the day had been a happy one for Juanita, it had also been fatiguing, and she needed no urging to go early to bed. But she did not fail to give mamma and papa their good-night kiss and to thank them over and over for her splendid outing—one that she would never forget.