| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

Father Rasle and His Strong Box

By HENRIETTA TOZIER TOTMAN PRELUDE ON THE picturesque waters of the beautiful Kennebec no village of the Indians presented more attractions than Old Point, where stood the pleasant little hamlet of Narrantsouk.1 "A lovely sequestered spot in the depth of nature's stillness, on a point around which the waters of the Kennebec, not far from their confluence with those of Sandy River, sweep on in their beautiful course, as if to the music of the rapids above; a spot over which the sad memory of the past, without its passions, will throw a charm, and on which one will believe that the ceaseless worship of nature might blend itself with the aspirations of Christian devotion."2 And one will turn from this place with the feeling that the hatefulness of the mad spirit of war is aggravated by such a connection with nature's sweet retirement. "Rasle's3 Village," a name oft used in place of Narrantsouk, was built on the land as it gently rose above the intervale. The huts were erected on either side of a path some eight feet wide. The church, surmounted by a cross, was neatly constructed of hewn timber and was by far the most imposing building in the place. It stood somewhat back from the narrow path, at the lower end of the village. Graphically described in the following lines of Whittier, is the chapel, the scenery and, lastly, the Jesuit priest. "Yet

the traveller knows it a house of prayer,

For the sign of the holy cross is there; And should he chance at that place to be, Of a Sabbath morn, or some hallowed day, When prayers are made and masses are said Some for the living and some for the dead; Well might that traveller start to see The tall, dark forms that take their way, From the birch canoe on the river shore And the forest paths to that chapel door; Marvel to mark the naked knees, And the dusky foreheads bending there. While in coarse white vesture, over these In blessing or in prayer, Stretching abroad his thin, pale hands, Like a shrouded ghost the Jesuit stands."

The church, richly decorated with pictures of the crucifixion and of other events in Biblical history, was well adapted to make a deep impression upon the minds of the Indians. "Silver plate was provided for the sacramental services."4 Father Rasle for it is he around whom this story centres with apostolic self-denial and zeal, had been laboring amidst the solitudes of that remote wilderness for a period of thirty-five years. He had made many converts and had won, to an extraordinary degree, the love and devotion of the whole tribe. By birth he was a gentleman of illustrious family, possessing accomplishments and education, isolated from home and friends, living in a cabin in the woods in a country foreign to his birth and surrounded only by the "white man's friends" as the Indians chose to call themselves. And yet in his letters to his nephew in France never can we detect a murmur in view of the hardships of his life. It seems difficult to imagine any motive sufficiently powerful to induce a gentleman of refinement and culture to spend his days in the wigwams of the savages, endeavoring to teach them the religion of Jesus, unless that motive be a sincere desire to serve God. The English Protestants brought with them to the new world a very strong antipathy to the bigoted Catholicism which had been the bane of the Old World. They did not love their French neighbors and were greatly annoyed at the recession of the Acadian provinces to France. The troubled times very speedily obliterated all the traces which the king's commissioners had left behind them. England was far away. The attention of her contemptible King, Charles II., to the remote colonies, was spasmodic and transient. It was to Massachusetts alone that the widely scattered inhabitants of Maine could look for sympathy in time of peace or for aid in war. There were no bonds of union between the Catholic French of Nova Scotia and the Puritans of New England. They differed in language, religion and in all the habits of social life. Those very traits of character, which admirably adapted the French to win the confidence of the. Indians, excited the repugnance of the English. The pageantry of their religious worship, which the strong-minded Puritans regarded as senseless mummery, was well adapted to catch the attention of the savage. Thus the French and the Indians lived far more harmoniously together than did the Indians and the English.

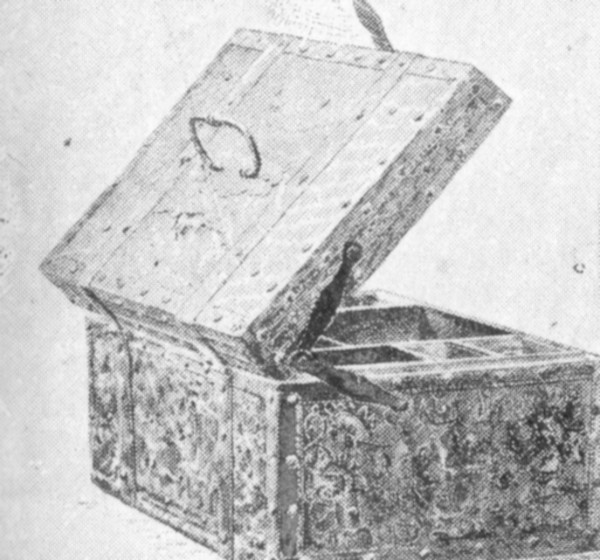

Captain Moulton had been an active military man in his younger days; but having been severely injured following the Rasle expedition, he had withdrawn to a country estate and passed his best years there with his wife and child. After he became a widower, a spirit of unrest seemed to drive him over the earth, and it was only from time to time that he made a brief appearance among his old friends. He was a stately, handsome man, even yet. His hair, although streaked with gray, stood thick and curly above his high, bronzed forehead and in his eyes gleamed a quiet fire which told of imperishable youth. At the time our story opens, in April of 1744, we find him and his idolized daughter, Sylvia, guests in the home of his sister in the prosperous village of York. SCENE I. AT THE FIRESIDE. "OF WHAT were we speaking," asked Captain Moulton, "was it not of people's inability to imagine situations which they themselves have never been through? How can one expect it of them since the individual himself cannot always comprehend what he has undeniably felt. When I look back to those troublous times and observe everything calmly from a distance, I almost question perchance Father Time is playing sad tricks with this memory bump," tapping his head by way of emphasis. The conversation now turned to the early days of 1722. "Yes," said the Captain, "the waves of party spirit ran high. So much discord existed between Gov. Shute5 and the House, that he, at length, tired of war controversy, without popularity, pleasure or emolument, formed the resolution of leaving the chair which he had filled some six years, and in December he embarked for England.6 "Our relations with the Indians had been assuming a bad posture and in some measure to overcome the feeling of hostility the government changed its more vigorous or violent measures to schemes calculated to soften the asperities of the Indians, and to Bomassen, an old, influential sachem of Norridgewock, they sent a valuable present, hoping to enlist his influence on the side of reconciliation." "But why a present to Bomassen more than to chiefs of other tribes?" asked Erick Lynde, who had just returned with his friend, Lawrence, from Fort Richmond, where they had been sent as commissioners by Gov. Shirley, to consider the rightful fishing sites and a prisoner.7 We toiled on and by a totally unexpected route thought to take the Indians by surprise. We arrived at the village undiscovered, but before we could surround the Jesuit's home, he escaped into the woods, leaving his books and papers in his 'strong box.'8 This we took and no other damage was allowed. Among his papers were his letters of correspondence with the Governor of Canada, by which it appeared that he was deeply engaged in exciting the Indians to a rupture and had promised to assist them." Here he paused, as if buried in thought. Aunt Anna broke the silence. "But, brother," said she, "there is more of interest. Have you forgotten the sealed package? You remember the faded name it bore Arich Synde and then in a clearer hand the words, 'From your loving mother.' " "Yes, yes, it all comes back to me, Anna. To be sure, memory plays strange tricks with us old people. I used to think that perhaps I might find the lad, but in all my travels, never once have I heard the name; let me think, we called the name "A rich Syn-dé am I right, Anna and where is the box and the package?" "I will get it for you," she replied and quietly retired from the room. "We don't want to weary you, Uncle," said Lawrence, "but that story of Captain Harman and yourself. It is the most thrilling of all and Erick, you know, is leaving us on the morrow." "Captain Moulton, your story draws a tear from my heart. It carries me back to my first recollection of Father Rasle and his followers, dearest among whom was the wife of Mogg,9 'The Fearless.' I can almost feel the warmth of her hand and the love in her song as she oft rocked me to sleep on her bosom." Turning to Lawrence, he said, "You know somewhat of my life, those twelve years ere the saintly father was killed by the hands of the English,10 and more I will tell you, but continue, Captain Moulton; it is the thread of your story that holds me. Perchance you may hold the link between me and my people. God grant it! I have wandered far and near since those days, when a wigwam was all the home I knew, and had it not been for the death of a son in the home of Thomas Leighton I might never have felt the warmth of a home fireside. He and his wife have given unsparingly of their love to me, but there is yet one prayer unanswered. May it please God to some day give me knowledge of my parents! There's but one known link between me and my mother 'tis this baby ring and the words engraved on it, "Erick Lynde Sept. 7, 1710." "We want more of Erick's life story," said the Captain, "and the box, we will open that, yes, here comes Anna! but I will first tell you of my last expedition." He paused. "Ah, but 'tis sad to relate and I would that it were not to pain you, Erick! You loved Rasle, 'Father Rasle' as you called him and what I have to tell you, may it never sever our friendship." "Never fear, Captain Moulton, here's my hand; 'Once your friend, always your friend,' is my motto!" "Well, then, here's my story and don't ask me for more, Lawrence. Age softens and dulls the edge and now I find in my heart love and pity for him who was friend to the 'redskins.' " Then in his direct, brief style he began his narration of the last expedition to Old Point. "Norridgewock being still the residence of Rasle, early in the fall of the year 1724, I think it was August, and the date of your birthday, Sylvia. You remember after my return that I taught you to draw with a stick in the sand, the figures 19; well, that was the date! I was about to tell you that I, together with Captains Harman, Bourn, and Bane (all good men), commanded a detachment of 208 men divided into four companies to march against Norridgewock. We left Richmond Fort, our place of rendezvous opposite Swan Island, on the 19th of August, 1724, and ascended the river in seventeen whale-boats, accompanied by three Mohawks. The next day we arrived at Teconnet, where we left our whale-boats and Lieutenant with a guard of forty men. "The residue of the forces commenced a rapid march at daybreak of the 21st, through the woods to Old Point, hoping to strike the foe by surprise. On the eve of that day, just as the sun was setting, we saw three natives and we fired upon them. The noted Bomassen,11 to whom Governor Shute and the House had sent that valuable present12, was one of them and with him his wife and daughter. The chief, while trying to escape through the river, was shot, his daughter we fatally wounded and his wife we took as a prisoner. A little after noon of the 22d we came in sight of the village where we had decided to divide the detachment, thereby hoping to encircle the village and cut off all escape. Captain Harman, imagining he saw smoke rising in the direction of Sandy River, and supposing that some of the Indians might be at work in their corn-fields, marched off sixty men, while I formed my men into three bands nearly equal in numbers. Two of these were placed in ambush, while the remainder were marshalled for an impetuous charge. "I commanded my men to hold their fire until after that of the Indians, then boldly and quickly advance, in profound silence. This they did and before their approach was suspected they were within pistol shot of the Indians. One Indian happening to look out of his wigwam discovered us close at hand. He gave a war-whoop and sprang for his gun. The consternation of the whole village seemed terrible. About sixty of the fighting Indians seized their guns and fired, but in their tremor they overshot and not a man of ours was hurt. Then followed the discharge from our men which disabled and killed many; this was returned without breaking our ranks. Then, fleeing to the river to escape, they fell upon the muzzles of our guns in ambush. Several instantly fell, others attempted to swim and some to wade across the river which was not more than six feet deep and about sixty feet wide. "A few jumped into their canoes but in their excitement, they had failed to take their paddles and thus were unable to escape. The old men, women and children fled in every direction. In their mad rush fire faced them on every hand. It was thought that not more than fifty landed on the opposite bank of the river, while only one hundred and fifty made their escape into the thickets who were pursued by us, but not overtaken.13 "Our men then returned to the village and here we found the Jesuit and an English boy14 in one of the wigwams firing upon a few of our men who had not followed the wretched fugitives. One of our captains, who has a 'spreading tongue,' said that he saw Rasle shoot the boy through the thigh and then stab him in the body,15 though he ultimately recovered, such I know for a fact as he was taken captive by the Mohawk who set fire to the village, and a year later accompanied Captain Bourn to Canada. I had given orders to capture but not to kill Rasle, but Jaques, one of my lieutenants, saw the Jesuit wound one of our men, and he then broke open the door and shot him through the head.16 I recall that Jaques in his effort to justify his disobedience, alleged that when he entered, Rasle was loading his gun and declared that he 'would neither give nor take quarter.' "Then there was a noted chief, an aged man, Mogg by name. Captain Bourn told us that he saw one of the three Mohawks fall when Mogg fired into their midst and this act so enraged the Indian's brother that he returned the fire and the old Sagamore fell dead. The soldiers quickly dispatched his squaw and children. Of his squaw I shall have something to tell you later; something quite foreign to man's nature, but close to the heart of a woman. But to go on. Near night after the massacre was over and the village deserted by the Indians, Captain Harman and his party arrived, and placing a guard of forty men, the companies slept in the wigwams. In the morning, when it was light enough to see, a search was made and, including Rasle, there were thirty bodies found cold and stiff stretched on the ground; Mogg, Job, Carabesett, Wissemement, and Bomassen's son-in-law, all known and noted warriors, were among them. Three captives were recovered, and one, who for years had found kindness and shelter in the wigwam of Mogg the noted, and four prisoners were taken" and Captain Moulton paused and sighed as though wearied by the painful recollection. Lawrence started to speak, then turned to Erick, his friend, but observing his clinched hands and unusual pallor, he asked " Are you ill? Does your wound pain you, Erick?" "No, thank you, not ill, but the fate of the boy captive has stirred my heart." And in whispered words continued, "Mayhap, I, who did live among them, who have known neither father nor mother, may be that most unfortunate English boy." Captain Moulton, who seemingly had seen not nor heard this brief conversation, took up the thread of the story and continued: "The whole number killed and drowned was eighty or more. Our plunder consisted of plate and furniture of the altar, a few guns, blankets and about three barrels of powder. "After leaving the desolate homes and well on our march to Teconnet, Christian, one of the Mohawks, whether influenced by some member of the party or of his own accord, suddenly left us, returned to the village and set fire to the chapel and cottages." Then, waxing eloquent as he oft did when he neared the end of a story or argument, "From the celebrated Canibas tribe, dating from this bloody event, the glory departed, to return nevermore. And down through the annals of history, since the death of King Philip no more brilliant exploit, in the Indian wars, has been recorded than this, our last expedition to Old Point. "You know me now as Lieutenant-colonel, but here by Anna's fireside, I am always 'Captain,' and I like it! Promotions are sometimes hard to win, but the men said that the distinguishing recompense belonged to me, but Harman, who was senior in command, proceeded to Boston with the scalps and received a reward for the achievement, the commission of Lieutenant-colonel. My men said that 'Superior rank had shaded superior merit,' but the universal applause of this country was mine and that was enough. My title of Colonel dates back to the days of Pepperell when I was made Lieutenant-colonel in the militia under his command. "I neglected to mention that while we were on our return to Fort Richmond, and without the loss of a single man, my old leg here was disabled due to the blow of a savage? No, due to a falling pine of the forest that made me a target." He rose. "Give me my cane, Lawrence, I am growing to be dependent upon it. A member of the Provincial Council and Judge of the Common Pleas17 suits me better now that Father Time has placed his finger upon me." "But, Captain, stay, here is the 'strong box,' " said Anna, "and the key hangs above the fire-shelf." Lawrence rose to get it. "But the story, your friend's story, Lawrence." And turning and laying a soft hand on her father's shoulder, Sylvia asked, "May we hear that before you open the 'strong box?' " "Yes, yes, daughter mine;" then he turned to Erick and said "let us hear your story now." "It is not much I have to tell," he replied, "this much and this much only, I know of my past. It came by the way of my old foster mother, the wife of Mogg. She told how the warriors fell upon Winter Harbor and returned bringing me, a baby, among other captives. That she pitied the wee, pink bit of flesh and persuaded Mogg, her husband, to allow her to bring me up with their children; that no blood of the redskins was in my veins, she felt sure, as Mogg knew of my mother, and that papers they gave to Father Rasle told something of my father. "Years came, years went; I lived among them, learning their ways, their religion, and feeling their 'big hearts.' Father Rasle I loved as did his Indian followers, and as a child I knew not but good of this Jesuit. Captain Moulton, those expeditions of yours struck terror to the hearts of those people. "May I return to your last expedition, following which, the Indians who had escaped to the woods returned to the smouldering ruins? "The story of the fall of the boy captive is false. I was that boy and the scar from the wound," laying his hand gently on his thigh, "is here, but it was made on the day before when I was out hunting with some Indians. I slipped and fell on a knife used by one of the men while dressing some fish for our dinners. The shot from Father Rasle's gun was aimed at one of your men, but just at that time he fell, by the hand of Jaques, and the gun changed position and I was the victim. Then realizing that escape was impossible, I hid myself in an underground cellar beneath the wigwam, and there I remained until Mohawk returned and made me a captive. We hid in the nearby woods and watched the Indians return to their deserted village. "Even the stoicism of the savage was overcome by the sight of the gory bodies. Their first care was to find the form of their beloved missionary. This they did, and with prayers and loud lamentations buried the remains below the altar, where the evening before he had celebrated the sacred mysteries and, having completed this task, they raised a rude cross to commemorate the memory of their loved one. Then, with such solemnities as they had been taught, they buried their chief Bomassen, whose body they found in the woods where your men had left it. Thus, having finished their painful task, they turned sadly from their homes which their ancestors had occupied through countless generations and sought refuge with the Penobscots. And from that date, blotted forever from the register of the Indian tribes has been the historic name of the Norridgewocks." "There is but one thing more before we separate for the night," said Anna, "Captain, if I am right this 'strong box,' which perchance Erick has seen in the past, has not been opened for a good twenty years. The papers may be worn and more faded, let us see." Whereupon Captain Moulton proceeded to unlock and remove one by one the contents. Lastly of all he came to the sealed package and holding it to the light read as before the name Arich Synde. Then, shading his eyes with his hand, he seemed lost in thought. Light seemed to break "Erick, come nearer. What is this faint line I see above the A? Does it help to form some other letter? Your journey takes you over our paths of old. Perchance you will find someone who has knowledge of this package. Take it and use it as you like. To me it can have no further interest and if left here it will soon break in pieces, the seal even now hangs too loosely." Then, closing and turning the key in the "strong box," he said, "The hour is late, let us separate for the night."

SCENE

III.

IN THE GARDEN. RICK arose and walked to the window; feeling depressed he stepped out on the lawn and walked to and fro on the lower part of the terrace, gazing absent-mindedly over the shimmering lake, and now and then hearing a detached word from the conversation of the people within. The warm night wind seemed as soothing as Mother Mogg's Indian lullaby legends; the stars blinked like eyes which can scarcely keep themselves open. A fine mist moved slowly across the heavens, weaving a veil over the shining firmament. A slight rustle of the grass and Erick turned to behold Miss Moulton. "Bear in mind," said he, "we shall be wakened from our first sleep by a spring thunder storm."  Father Rasle Monument at Old Point He had never seen her so beautiful; her face was unusually pale; her beautiful eyes glistened as if a slight shower had passed over them. A certain air of timidity made her seem girlish, indeed. Never before had he felt so clearly what a treasure she would be to a man. "You are ill," he said, "you are suffering from the sultriness." She neither answered nor glanced at the heavens, but continued to look fixedly at the ground. Suddenly she began, "So you are leaving us on the morrow, my father tells me." "Yes, Miss Moulton," he replied, "the date of my departure is at hand, and need I say that I would gladly tarry longer did I not wish to visit the scenes of my early childhood and more than all else the spot where stood the old fort in which my mother sought refuge only to meet death, and from which I was carried away to Old Point by the Indians when hardly more than a babe in arms. "I am indeed loth to leave this place, these friends, and, may I add, deeply grieved most of all to leave you. "I shall not trouble you long, but I must talk with you. It has been clear and comprehensible to yourself and to me for a long time, yes, ever since the first eve we met. It is always best not to close the eyes and seal the lips when people love each other. You have heard my story and you love me, I feel, I can see, I know in spite of everything." Her eyes were raised to his for an instant. "Thank you for those words," she said. He would have taken her in his arms but she repelled him in gentle firmness. "No, stay there, we will talk it over calmly," she said. "I am no heroine and this discussion is very hard for me. But tell me, have you spoken to my father?" He assured her on his honor that no word of his had passed his lips which could have betrayed the state of his feelings. "He is all to me that a father could be and I am the object of his deepest devotion," and here she paused. "It pains me to say it. But I could not shatter his confidence in me, even though it cost me my future happiness. There are still and were noble men among our Indian brothers, but, knowing my father's dislike of the redskins, and his promise to my angel mother, I do not know how he will receive you, even though you are the best of friends." They stood facing each other in sorrowful silence. He seemed to feel that any word, any assurance of his good faith would be trivial, a desecration of the situation which she regarded so nobly and purely. "I feel much better now," she said, with an indescribably brave and beautiful smile. "Do not think any more about it. Good counsel comes in the night. No one is responsible for his inclinations, but only for his deeds, and you, I know, will never do anything which could really divide us." She gave him her hand and was about to say good night when her father approached, and together she left them. "It has driven me out also," he said, as he walked beside Erick and, stopping for breath, glanced at the starlit spring heavens. "When I saw you slipping out, a melancholy envy, which you must pardon, come over me. We spent so many happy hours here together, reviewing the sad past and living so completely in the joy of the present. You, Erick, and Sylvia have brought new color into my life. The buoyant spirit of youth has seemed contagious. Even this crippled leg of mine has grown young again." He put his arm in that of his young friend and they walked slowly down the garden path. "You are leaving us on the morrow," he continued. "We shall miss you. You will always seem a part of this dear old place where we met. Our friendship is not of the passing day and though we meet not again, in our hearts your memory will linger. I admire your courage and I can only wish you God-speed in your undertaking. You have but the sacred memory of a dear, departed mother, and I feel that you can believe your foster-mother's story. May it please God to give you knowledge of a father, worthy of such a son." He paused, seemed lost in reverie. Erick hesitated, then broke the painful stillness. "Captain Moulton," said he, "my time is brief. I was about to go in search of you. May I have a word in private?" They had turned and were approaching the house. He paused as though scenting a situation which might call up old memories, then, he said, and his voice was saddened, "Go on!" "It is this: I love your daughter and my love dates from the moment when first we met. I can never again be my own master, even though I should be obliged to remain away from her forever. Until less than an hour ago, no word had passed my lips. By accident we met in the garden. I could not longer endure the uncertainty as to her feelings and I told her." Erick paused, then pained by the awful stillness, he continued: "An unspeakable grief suddenly seized her almost as though a hot buried spring had burst from her inmost soul. In that instant she knew that she loved me, but noble woman that she is, she bade me go to you, her father." Like the commander of some fortress, who, recognizing the superiority of the besieger, needs no council of war, yet if time can be won, everything may be saved and the relief may come which would have been too late if there had been a premature surrender, so he waited, and then sank upon the grass, one hand supporting his massive head. Erick awaited the words he might utter in strange suspense. At last he spoke, and his voice was measured and saddened. "The symptoms are, indeed, precisely the same as when I fell in love with my wife! But the situation is different. Not that you are unworthy of my daughter's hand. Knowing you as I do, gladly would I give it in marriage, but the promise the promise to the loved one who is sleeping. Can I break it? 'A barrier lays between us, invisible, yet not unfelt.' " Again his voice sounded, "But one curtain remains to be drawn aside. The finger of God, my poor boy, will guide you. Go search the wilderness for some person who has known your mother and perhaps from those lips her life's story will come as a heritage to you, her son. Secret were the hiding places of the Indians. Twenty years and more since you lived among them, unearthed, in the meantime, may have been many of their treasures and secrets. This worn frame of mine is sadly equal to such a journey, but if light breaks for you, as prompt as to the response of a bugle call, Sylvia and I will hasten to join you and there on the spot where fell the priestly father, you shall receive the hand of my daughter." With a silent grasp of the withered hand the two men parted. "Is all of love all of life denied to me?" sighed Erick. Then, without more delay, he turned and approached Sylvia who stood somewhat apart, near the arbor. Plainly evident was the sorrow that lurked in his bosom, yet with the manner that bespoke the man schooled to obedience, he said, "I ask you nothing, Miss Moulton, but to wear this ring which was once my mother's, the story of which you have heard. I may not live. We may never meet again, but I do ask you to remember me. Nothing can make us enemies at heart." Slowly the dark beauty raised her beseeching eyes to his saddened face. "Do not think that I do not feel. You will always be in my heart," said she. "The God above us will guard and guide you." He kissed her trembling hand and felt within his own the little locket she had ofttimes worn, which later showed to him her beloved face and a lock of her silken, brown hair. Turning as if to depart, he heard the reluctant whisper, "I cannot lose you forever from my life, Erick. We shall meet again. Something within me whispers that my father will be called upon to fulfill his promise. We shall meet again!" And then he gasped under his breath, "My own poor darling mine to eternity! We will meet after these days of doubt are no more!" SCENE

IV.

IN SIGHT OF OLD POINT. "MY JOURNEY has been uneventful," he muttered, as the hot sun of mid-summer beat down upon him, and he threw himself beneath the shade of a friendly tree on the banks of the Kennebec, looking up the river toward Old Point. "My search for some clue finds no reward." Then he took from his pocket the locket and gazed long and sadly at the likeness within. "Can I lose you forever? No, a thousand times no!" His head dropped between his hands and he seemed lost in thought. Suddenly he lifted his head and exclaimed in a voice that brought the echo from the near-by forest, "I have it, I have it! Let me see, yes, here it is in my pocket." And he drew forth the package. "The same mark Captain Moulton suggested," he exclaimed, "a line, curved, just above the broken initial and once it might have been a part of it, E is now clear, but what of the last letter h, well, that, too, shows a break by the pen and may have been made for a k if so, it is my Christian name Erick, but the S, in the surname, that alone is the lost link in my chain." Again he seemed lost in thought, while the package he held in his hand. "Can it be," he cried, turning it over and he bent to pick up a piece of paper that had worked itself out through the half-opened end and, in turning, he saw the words unfaded, clearly written. "Erick Lynde 1711."

"It is mine, mine own," he gasped. "The one link in the chain Can I read it?" "Is all of love, all of life denied me? We shall see!" he exclaimed. With mental fear and trembling, Erick read his dead mother's narrative. It was, after all, only a baffling disclosure, a series of half confidences, punctuated with more or less self-accusation, and evidently written at different times, with a reluctant pen and carefully copied from an original which had probably been destroyed. But one purpose ran through the whole narrative. The fixed determination to conceal names, dates, locality and all the surroundings from the son, who was now called upon to sit in judgment upon the proud woman who had given to him the breath of life. "Loving heart, self-tortured woman," he sighed. It was a strange story. A young, orphaned Colonial girl, in the flush of early womanhood; a desirable heiress in her own right, at a watering place in southern Italy met her fate, in the person of one of the titled families in England. Marriage united a Catholic lawyer with a Protestant child of freedom. The unbroken happiness of the first year of the marriage, the lengthened honeymoon, the wonders of the new world followed. The veiled resentment of the groom's family exhibited to the bride, together with the impressive loneliness of a vast, unbroken country in which they had found a home, where the husband was sent as an agent of the English King; all came as a blow to this girl-wife. The husband, leaning toward politics and public life, was recalled to accept a more fitting position in the country of his birth. Vainly his sorrowing wife implored him to defer the acceptance of the call to his country's service, until she might accompany him. At first he turned to her a willing ear. Then came the fierce vengeance of an unbridled nature, and the husband, whose fiery passions were his only law, left her, to seek renown in other lands. The conviction that she, the object of his heart's devotion, now approaching maternity, was thus deserted, shattered forever the fond ideal of the northern wife. That the young wife would soon forget and at last forgive, that she could be won back by time and the birth of the expected heir, was the delusive hope which contented the sullen husband. The record of a year followed in which no line of hers reached his eyes, no trace of her could be found. The possession of independent means made the revolted wife impregnable in her self-concealment. Then came an account of an attack upon Kittery, and, through some mysterious course, she allowed the report to reach England of the untimely death of herself and infant son. Erick read the bitter lesson of the trusting wife. "It is the grist of the Gods," he sadly murmured, "that this strong-willed English aristocrat should accept the seeming verdict of fate. "My mother has found that peace which passes all understanding, but my father, if he lives yet, is environed with all the dark horrors of war. My poor mother was only a victim of that false social system which makes one standard for the woman, another for the man. And my father is the wretched heir of the ingrained sins of his ancestors, the mere puppet of the peculiar institutions." Erick had now reached a mental calmness and at the sound of the fallen journal, as he supposed, he reached for it and saw that it was only a letter that had found lodgment within the journal. He stooped to pick it up and read in unfaded words, his name "Erick Lynde," and yet another "Erick Lynde Goffe, from your sorrowing Mother." Before breaking the seal he carried the missive to his lips. Then solemnly pondered the final words of his dead mother's disclosure. "Years have taught me both charity and justice. I give to you no guiding counsel for your own future actions. That your father has been a man of mark, of high public station, of unsullied personal honor, since his departure from me, is known to me. I frankly admit my own moral desertion of the man to whom I had plighted my wedded faith. I see now the grievous wrong inflicted upon him. I should have gone to him as he desired when your tender months were equal to an ocean voyage. I have given to you all the life, half of which I owed to him, and only you can decide upon the rightful course to follow. Condemn him not, and if, perchance, believing in the report of my death at the hands of the Indians which I allowed to reach him, he has surrounded himself with wife and with children, for my sake, work no wrong to the innocent ones of his household. For nearly two years I have not followed his fortunes save merely to know that he lives. In making these changes of residence, in my final retreat to Falmouth and the adoption of my disguise of the name of Lynde, I have absolutely prevented suspicion and discovery. Your father hopelessly accepted my subterfuge of the Indian massacre, in good faith. He must not be held accountable for my wrong doing." "As God wills," mused Erick, as he had exhausted the final words of loving tenderness with which "Louise Lynde-Goffe" had closed the recital of her blighted life. "Naught in my heart to condemn thee," he whispered. "He that is without sin let him cast the first stone. Thank God, there is now no barrier between Sylvia and myself." Erick was strangely agitated as the messenger rowed down the river bearing his brief message which read: "Come, I await you, here at the grave of Father Rasle, my past as an open book, shall be read by you and I doubt not your decision." Signed, "Erick Lynde-Goffe."

SCENE

V.

AT THE FOOT OF THE CROSS. THE setting sun had followed the rising sun, and the rising sun the setting sun for many long days ere the promise to join Erick in the north was fulfilled. It is early autumn. At last we find them at Old Point on the ground where fell those brave warriors, slowly wending their way toward the grave of the Jesuit. Captain Moulton walks but slowly, and the limp in his leg is more perceptible than of yore. "Your father has aged since I left your Aunt Anna's home, and saddened he seems, by the tales I have told of the English boy captive. The way has been long, too long, perchance, for the aged, but I wanted you to see and to feel the same spirit of love for this deserted, hallowed spot, that I felt as a child for this ground, then the famous Indian village." They were approaching a little enclosure, a grove of ash trees, and in the darkest corner of the shaded place stood an empty bench. "Captain Moulton," said Erick, "might not you like to rest here in the shade while your daughter goes on with me to the rude cross, you see yonder?" "Yes, tired is my leg and I will gladly rest till your return." So saying he dropped himself wearily down upon the bench and they left him. Onward they walked in silence, "too sacred seemed the spot for mere words." They had reached the foot of the cross and taking from his pocket a time-yellowed, faded paper, he said, "Sylvia, will you read my dead mother's journal?" She reached forth her hand but withdrew it. "Why, this is the package so long kept from eyes in the 'strong box!' " she exclaimed. "Yes," he replied, and his voice sank to a whisper, "your father had in his possession the lost link that connected my past with my present." Again she extended her hand for the letter, then carried it to her lips, and between them fell a silence, unbroken. Erick remained seated for a while with his eyes closed, in that stupefied state between pain and pleasure which usually comes to one who has done his duty at the cost of a deep heart's need. Suddenly Sylvia looked up and her eyes, as they met his, were full of gratitude, but streaming with tears. "The more I give to thee, Erick, the more I have, for both are infinite." Then rising and with hands outstretched to him, she said: "Come, let us go to my father." In the year 1833, Benedict Fenwick, bishop of Boston, repaired to the site of the little chapel of Rasle, in Norridgewock, and on the anniversary of its destruction, August 23, erected a monument to the memory of the self-denying missionary. The writer of this article, while enjoying the beauties of nature on a trip through the Kennebec valley, visited this historic spot and was much interested in the monument as it stands to-day. A large block of granite, surmounted by an iron cross, gives an imposing height of eighteen feet, measuring from the foundation to the highest point of the cross. A Latin inscription, of which the following is a literal translation, is cut in the stone; a copy of which was kindly offered to the writer, by an aged priest, who was there that day studying the monument which occupies the spot where the altar stood before the church was burned, and beneath which rest the remains of Father Rasle. *

* *

"Rev. Sebastian Rasle, a native of France, a missionary of the society of Jesuits, at first preaching for a few years to the Illinois and Hurons, afterwards for thirty-four years to the Abenaquis, in faith and charity; undaunted by the danger of arms, often testifying that he was prepared to die for his flock; at length this best of pastors fell amidst arms at the destruction of the village of Norridgewock and the ruins of his own church, in this very place, on the twenty-third day of August, A. D. 1724. Benedict Fenwick, Bishop of Boston, has erected this monument, and dedicated it to him and his deceased children in Christ, on the 23d of August, A. D. 1833, to the greater glory of God."

AUTHOR'S NOTE. The writer of this article desires to state that this narrative for the most part presents facts in the setting of fiction. While the methods of fiction have been employed, they have not departed from the historical spirit. Captain Moulton and Erick Lynde have been made story tellers, but their stories are substantially true. The incident of "Father Rasle's strong box" with the one exception of the "Journal," is true. The decision of Father Rasle against whatever odds to struggle on for the cause of human justice and a closer following of Christ, is one of the noblest examples of moral heroism.

____________________ 1 Father Rasle's spelling as used in his letters to Vandreuil, Gov. of Canada Narrantsouk Indian name for Norridgewock. 2 Francis in his "Life of Father Rasle." 3 Jesuits' M-S. Dictionary of the "Abnaki" language gives spelling Rale (often used), Rasles or Ralle, used by different writers. 4 Williamson. 5 Samuel Shute, Governor 1716-1722. 6 Samuel Shute, Governor. Left for England, Dec. 27, 1722. 7 Rasle's letter. 8 Coll. Mass. Hist. Soc. p. 266-7. 8 Williamson speaks of the "strong box" as having been stolen by the English at this time. 9 Mogg famous Indian chief Norridgewock. 10 Williamson: "The general feeling of the British towards Rasle was that of the most intense hostility." 11 Drake's Book of the Indians Bomassen's death. 12 Governor Shute, 1719. 13 Opinions differ as to numbers. 14 Several authorities state that an English boy about 14 years of age was taken captive by the English, 1724 "Last expedition to Old Point." 15 Hutchinson (2 Hist. p. 282) says this act of cruelty was stated by Captain Harman, senior in command, upon oath. (But still is doubted 8 Coll. Mass. Hist. Soc. 2d series, p. 257.) 16 Williamson. 17 Williamson, p. 226. |