| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

The

Luck of the Juliet: A Tragedy of the Sea

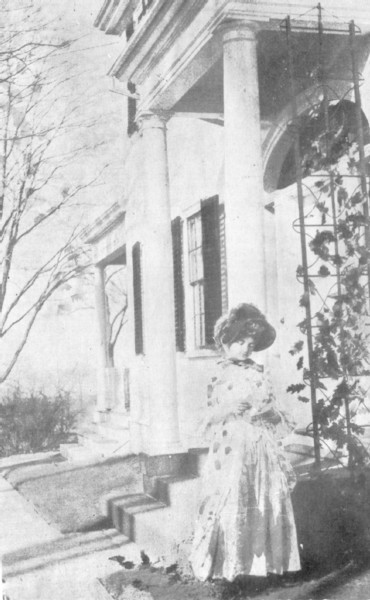

By LOUISE WHEELER BARTLETT MINETTA Hodsdon stood on the steps of the old Colonial tavern and looked first up the street and then down. She was watching for Ned Brown, her sailor lover. He had agreed to call for her for their usual Sunday afternoon walk. It was now almost half-past three. She looked over to Ned's house, only a stone's throw distant, but the house was wrapped in Sabbath peace. Beyond, on the slope of the hill, at the old Gay house, where her friend Ethel Snowman lived, she saw Ethel and her husband John looking at the vines around the doorway. Minetta waved her hand and looked about her to discover any traces of new spring green peeping through the black earth around her own doorway. The big, pillared door, with its fan light over the top and its polished brass knocker, made a fine background for her as she stood there. Minetta was pretty, scarcely more than seventeen. She was slender, so slender that even the full skirts and furbelows of the days of the Rebellion could not detract from her figure. She had a mass of yellow curls, large violet eyes and plenty of pink in her cheeks. She was sweet natured, usually as angelic as her appearance, but when occasion demanded she had plenty of fire, as Ned Brown was to find out later that day. When Captain Hodsdon was confronted with the problem of taking care of his two motherless daughters, he decided to quit the sea and put his savings into this old tavern. Later, he had the chance to continue his hotel management and also be sailing master of the old packet "Spy," which plied between Castine and Belfast. He was a genial host, who kept his guests in a good frame of mind with his fund of witty stories. So they soon learned to overlook such minor inconveniences as tough steak and poor service. He made a success of his inn by sheer force of his own strong personality. The other daughter, Maria, was as fine a girl as Minetta, several years younger and her exact opposite, with gipsy coloring, dark hair and big black eyes. Maria had begged to go to walk with her sister this sunny April day, but Minetta had been firm in her refusal, for she had an important question that she wanted settled between herself and Ned this very afternoon. It must be settled, if she were to get her clothes ready to be married in June, as Ned was now urging. Minetta had just time to loosen the dirt about five new-born crocuses, when she heard, first Ned's whistle and then his footstep on the flag walk, as he came around the sprawling ell of the house. Ordinarily she might have taken Ned to task for his tardiness, but not now, with the favor which she had in mind to ask of him this afternoon. Ned came up to her with an eager smile and squeezed the firm little hand which she held out to him. "Sorry, Netta dear, to keep you waiting. I've been up on Captain Davies' piazza and he has been telling us fellows some mighty interesting war stories. Wish I could tell a story the way he does. He makes you see the whole thing before your eyes — the regiments of soldiers, the smoke and roar of cannon and all the glory of battle. It was so hard to break away, that's why I'm late." And his face flushed with enthusiasm in spite of his apologetic tones. It was so good to walk in the warm spring sunlight, that, not minding the mud, they went up to the fort and along the upper road, by Ober's little farmhouse, almost out to the light at Dice's Head. Then they swung around by the white stone cottage at the bend of the road and looked out over Penobscot Bay to the distant sea. Suddenly Minetta said, with a quiver of her lip and a half sob in her throat: "It won't be long, Ned, before you will be sailing out there on your way to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and I shall be standing here alone watching you out of sight." "Don't think of that part of it, Netta. Remember, by that time you will be my wife. Rather think of the day when you will be standing here watching our little schooner coming up the bay to greet you," replied he. When they reached Mogridge's barn the bars were up across the road. Ned offered to take them down but Minetta liked the fun of climbing over and Ned liked it, too. For when she stood on the topmost bar, poised like a bird for flight, he put up his arms and lifted her down. He held her close for one precious moment, which might have been longer if Mrs. Mogridge had not come out of the barn with a foaming pail of milk and destroyed the sentimental value of the scene. Finally, as the sun was getting low, they came along the beach past Webster's shipyard and the Noyes shipyard to Tilden's yard and the lumber wharf, to look at a schooner being built there. Minetta was crazy over the little vessel, and that was why she guided Ned's steps that way. They went over the vessel and looked into the cabin and the cook's galley. When they were back on the wharf they leaned against a pile of lumber and talked her over. Minetta said, "Oh, Ned, I just love this little schooner. She is the sweetest one ever built here. Ned, you must get the boys to name her for me. My heart is set on it." "But Netta, dearest, I am only one of sixteen, and I can't name her for you. We've all agreed to call her the 'Juliet Tilden' after the Colonel's wife." That cut Minetta to the quick. She stamped her foot and said it should be named for her, and she was going to christen it with a bottle of wine, as she had read they did in foreign countries. Ned kept discreetly silent. Then she tried the coaxing method. With an adorable pout she put her pretty arms around his neck and said: "Don't you love me? Don't you think me as pretty as Mrs. Tilden?" "You're the sweetest thing in the world to me," said Ned, but he could see she did not believe him, and in a moment she came back with these words: "You don't mean it; I know you don't. I have heard you say a dozen times that the Colonel and his wife were the handsomest couple that ever walked down the gang plank onto steamboat wharf." In her disappointment she was almost jealous of the lovely, stately Juliet. She ended the discussion with these words: "Ned Brown, if you don't name this schooner after me, I shall not marry you in June. You may just wait for me until I am ready — perhaps December, or any old time. Listen to what I say. This schooner will never have any luck if you do name her 'Juliet,'" and under her breath she said something to the effect that, like Shakespeare's heroine, both Juliets would be fated to an early grave. She then turned on her heel, and without looking back went home to her supper. Ned, with both hands stuffed deep in his pockets and a crestfallen look about his mouth, such as a man generally wears when his wife or sweetheart has had the last word, went whistling over to the other side of the wharf. There he found his brother Andy and several other boys, their feet hanging over the edge of the wharf and their backs against another pile of lumber, smoking, whittling and talking over the matter they had just heard the lovers discussing. Could Minetta's words be called a prophecy, would they curse the schooner? This was the first disagreement they had had since they had been keeping company, but he understood Minetta well enough to know that a night's sleep would help matters out and she would soon be her usual agreeable self. So Ned joined the boys and tried to dismiss the whole fuss from his mind. These were the days of '66 and '67, right after the close of the Civil War. Owing to the injury done their shipping, New England's seaports, as well as those of the South, were having bitter days of reconstruction. Castine had suffered heavily. She had contributed her full quota to the Union cause. Colonel Tilden had returned to his native town, bringing his old white charger as well as a record of heroism of which the citizens were justly proud. The story of how he dug his way out of Libby Prison was the talk of the youngsters on the street. There was no favor too great for any Castine boy to do him. When the idea of building a schooner on shares was started, all the young fellows in town were eager to work on her if the Colonel would be agent and advance a sum sufficient to start the project. Sixteen men from eighteen to twenty-five years old put in some $700 each. Part of this was cash, but some of it represented the work that each one did on her. All of the boys in those days knew enough to lend a hand and do an honest day's work at shipbuilding. Many of these young lads learned some other trade, but when times were slack, worked at ship carpentry, and in the evenings went to apprentice school. They went fishing up in the Bay Chaleurs from the first of June to the last of September. Those were the days of good profit in fish and they sold their fare for a tidy little sum, which might be laid away for a nest-egg against the time when they desired to marry. *

* *

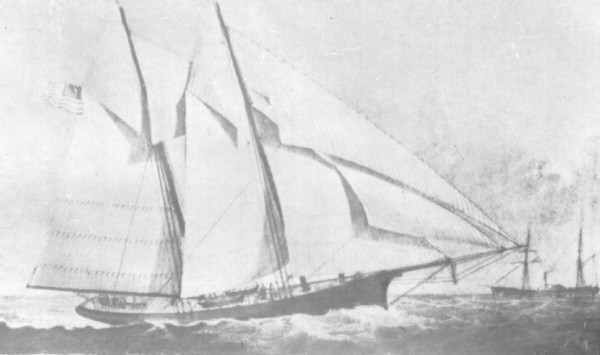

The days of Castine's supremacy as an important business port were over. One by one her industries had declined. The glory of being the shire town of Hancock County had been taken away from her; the useless court-house and jail were empty. The brickyard had failed. Instead of five shipyards echoing to the cheerful tap-tap of the hammer, it was good luck if one ship were launched from one yard, each spring. Her weekly newspaper, which had been the best and largest in this part of the state from 1799, had died a natural death from lack of patronage. Where ten ships from native or foreign ports entered or cleared during a week, bringing or taking large cargoes, the average now was perhaps one in a fortnight, and that, from Boston with freight, or a lumber or fishing schooner bound for the Provinces. The townspeople were discouraged and were even then looking about for some new enterprise to help the town to recover her former prosperity. The glory of her historic honors would always be hers, but the prestige of the normal school and of a health giving summer resort were yet to come. The "Juliet Tilden" was the prettiest sharp-nosed racing schooner ever built for mackerel fishing and must have cost about $18,000. She was the last vessel built in the Tilden shipyard and very few were built afterward in the town. That long line of fine old sea captains which included so many of the prominent Castine families, the Whitings, Gays, Brookses and Dyers, was no more. Many had retired from the merchant marine service to enjoy their last days with their families in comfortable Colonial homes. Ships from Cadiz by way of Liverpool or from Hong Kong around Cape Horn were no longer an every day occurrence. It was only now and then that a yard sent out a fishing schooner.  Minetta The launching of the "Juliet" occurred the middle of the week. Ned dropped in to the Castine House on his way to it, to ask the Hodsdon girls if they would like to see it. Minetta been had had plenty of time to think over her rash words. She had been unhappy over the falling out on Sunday and was quite ready now to meet Ned half way and even more, to restore friendly relations. So she called Maria and the three went over to the shipyard to see the staunch little boat slide down the greased ways. Half the town was present; the wharves were black with spectators. There were no ceremonies and no christening scene. It took some little time after the "Juliet" launched to get her rigged, painted and fitted out for her maiden voyage. She started out the first of June so as to get up to the Bay of Chaleurs in time for the spring school of mackerel, which runs in there strong about that time. Some springs the bay is packed full of small fish which are chased in by the larger fish. This year it was a poor school and the fishing fleet did not do as well as usual. It was a wrench to her heart strings, the day Ned left her, but Minetta was young and interested in the things of life worth while. She found that the long June days went by much more quickly than she had anticipated. Almost before she knew it, was time to be on the lookout for the vessel's return. She had received several short letters from Ned, mailed from different ports where the "Juliet" touched on her way north. The "Juliet," returning from her first trip, sold her fish on the way home. The captain, Benjamin Sylvester, was from Deer Isle. He wanted to see his wife and babies, so he took the "Juliet" into his home harbor. The Castine boys sailed up in a small sloop to see their families, and get fresh supplies and clean clothes. They were to rejoin the vessel for her second trip to the fishing banks. The young people had a jolly fortnight while the boys were home. Hayrack rides around the Square, dances at the old Avery place and clam-bakes at Indian Bar filled in the days. Ned Brown was a restless chap when off duty and he wanted something doing every minute. With the exception of what Minetta had threatened to Ned, there had been no thought of disaster connected with the "Juliet." What Minetta had said was only the chatter of a peeved child, about which only three or four persons knew. All of a sudden, a change seemed to come over every one connected with the little schooner. John Sawyer said he had a feeling that the second trip would not be a success, so thought he would not go. Will Morey felt the same. John was persuaded to go, but Will stuck to his original decision. Perkins Hutchins told his father been at he would rather help him tend the light. Perk's father had been given the government job of lighthouse keeper, but his father said for him to go along to sea and not show the white feather over nothing. In the meantime, the old "Morning Star" had started out on a trip. The "Star" was a rather rotten old tub, but she was the best to be had at that time. About a dozen Castine men were on her, among them Charlie Clark, who had just married one of those smart Hatch girls. At this time his wife was "off the Neck" visiting relatives and Charles' brother Will went off to see her. He tried to get her to come back to the village, urging that he was going off on the "Juliet" the next week, and that she write a letter to her husband, which he would take, as he would see Charles either at Bay Chaleurs or the Magdalen Islands. Sarah told him to come off two days later and she would have her letter ready. On Saturday Will went off again, taking his sister with him. He insisted that his sister-in-law come back with them. He said, laughing, "You may never see me again, for I am going on the 'Juliet,' and she is getting a black eye just now in the village." So Sarah walked in with Will and his sister. As they got to the top of Windmill Hill, they saw a man just about the build of Will Clark standing at the corner of Perkins field at the edge of the road. It was almost dusk and they thought he was someone they knew waiting for them, but when they got almost up to him, he turned and walked slowly in the middle of the road down State Street hill. If Will walked fast, so did the stranger; if he slowed up in his pace, so did the other. Will called out to him, "Hold on a minute! I want to speak to you." But he made no answer. He was in front of Ordway's cottage, and all three were looking at him, when, like a flash, he disappeared. No one saw which way he went; it was as if the earth had opened and swallowed him up. The girls ran, pale and frightened, into Mrs. Clark's kitchen, where she was frying buckwheat cakes for a late supper for them. With teeth chattering they told her what they had seen. She said it was an apparition. She remembered her grandmother saw one just before her youngest son was shot in the War of 1812. She thought probably second sight ran in the family. Just then Minetta came in, and, all three talking at the same time, the girls and Will told their story to her. As can be seen readily, when Ned Brown went to say good-bye to Minetta Hodsdon, he found her very nervous. She had heard the various stories that the men would not ship a second time. That very day Josiah Hatch had refused to ship, for fear he would not come back from a second trip. Minetta cried and told Ned she had not meant to cast evil on the "Juliet" by what she had said before the launching. She tried her best to persuade him not to go. She did not know a Brown, however, when he had made up his mind to go to sea. Ned Brown was a general favorite in town. He was tall, well-built and light-haired, like all the rest of the Brown family. He had smiling blue eyes, a frank mouth, in fact, he was a good, wholesome lad, with honest face and cheerful disposition. He feared neither man nor devil. Unlike most seafaring men, he had not the slightest particle of superstition in his makeup. He only laughed at Minetta's fears and said, "Don't worry, Netta. There's nothing in it. What shall I bring you home for a wedding present, if I stop in Boston or Portland? Remember, our wedding is to be in December, sure." Minetta blew him a kiss from the tips of her fingers, and, laughing between her tears, replied, "All right, Ned, I'll be ready December 31st." A trip to the Gulf of St. Lawrence meant very little to Ned, with one brother taking trips to Hong Kong and another brother to South America. The Browns belonged to a sea-faring line. His grandfather, a Scotchman, went to sea and his own father followed the sea until he was injured in some sort of a naval scrap at Gibraltar. Then he came to Castine and went into business. He was a fine old man, very well read, and could spout page after page of Walter Scott's novels and Bobby Burns' poetry. His wife, Ned's mother, was the salt of the earth and fully as necessary, as she comforted and sympathized with all the town's afflicted. After Ned left Minetta, she went over to the old Gay house to see John Snowman's little wife. She found her a sorry-looking object, as she had cried so much that her eyes looked like two burnt holes in a blanket. She was all broken up at the thought of John's leaving her. She, too, felt that it was to be an unlucky voyage. Bad luck seemed to be in a whisper floating in the air for those who would listen to it. John thought his wife hysterical, but was very kind and gentle with her, as she expected to become a mother late in October. He considered her nervousness entirely owing to her condition. He felt it was hard for her, as she was only a young girl, and he wished he could remain at home. But he needed the money and he needs must go. He left her sobbing on the shoulder of Netta, who promised to take good care of her. The personnel of the "Juliet's" crew was made up almost entirely of young men. There was Captain Sylvester and his boy. In a fishing trip like this there is not much authority in the captain. All the men own in the vessel and in one sense they are all captains, but one man has to handle the papers and be known at the custom-house as the captain. The list of men was: Ned and Andy Brown, Joseph Bowden and his son, Sam Perkins, Wells Wardwell, John Sawyer, Ira Wescott from North Castine, Perkins Hutchings, Cyrus Wardwell, Charles Eaton, Edward Clark and his brother, and Will Clark, a cousin, and two Snowman brothers, John and Frank. The "Juliet" left Deer Isle about the first of August and that very night Mrs. Clark, Will's mother, dreamed that she saw the "Juliet" on a great rocky reef, with her hull raised high in the air and her broken mast buried in the sand. Her daughter-in-law, Sarah, dreamed of seven white horses in a row in their stable, which was a sure sign of disaster to some member of the family. *

* *

"He will take his toll, he will take his toll. Mark my words, the monster hunts for his victim to-night," chanted old Granny Goode-now, as she hobbled along the beach in front of her snug little cabin, picking here and there a stray bit of driftwood, just the right length for her small kitchen stove. She was speaking to that rough old sea dog. mariner Ebenezer Mann, as he sawed for a fireplace a few big drift logs, which she had rolled away from the incoming tide. "Yer right, yer right, granny," groaned Ebenezer, as he straightened out his game leg and rested from his labors. "When the wind Maws up from Cape Rozier and th' water moans over Naut'lus bar, look out fer a storm before dawn, if the sky-line is streaked with lemin color and perpul, as 'tis ter-night. It war jest sech a night as this when th' British bark 'Jane' war wrecked on Trott's flats." Granny and Captain Ebenezer had cabins side by side on Oakum Bay at the north end of the town. Neighbors for these forty years, since her husband and his wife departed from this vale of tears, they had found it possible each to aid the other in such a manner as partly to mitigate the loss each had suffered. Many a darned sock bore testimony to Granny's skill with the needle, and never a batch of doughnuts went into its crock without half of it being left at the mariner's door. The sawing of driftwood, the loan of a daily paper and a portion of his sea catch proved equally his neighborly interest. As Minetta carefully picked her way over the wet stones of the beach and climbed the breakwater into the old shipyard, she heard the words of the two old people. She wondered what they muttered over; who was the monster, what the toll, and where the victim. She was hurrying home before the gathering storm. She had been across the river to Polly Coot's Cove, to gather there some big white scallop shells. She expected five of her girl friends to supper the following evening and she needed some big shells in which to serve the devilled lobster. Their negro cook at the tavern served it like crab meat and lobster was much cheaper. As she reached the house the wind and spray were dashing madly against the front windows. The rain was already descending in torrents. She ran up to the big front room, which was hers at this season of the year. There she lighted a fire in the big fireplace. As she changed her wet shoes and stockings and dried her damp skirts before the glowing blaze, she cast every now and then a furtive glance out over the black and angry bay. Whenever the house shook in the strong teeth of the gale, she shivered and murmured, "God look out for those we love who are on the sea to-night."  The Mackerel Schooner She could not sleep during the two days that the sea lashed the coast and hurled its defiance. Others besides Minetta wondered what was happening north of them and how the little fishing fleet would stand it at the mercy of the pitiless sea. *

* *

The "Morning Star" left Castine two weeks earlier than the "Juliet Tilden." She carried Castine men only. She got one fare of fish and made for the Gut of Canso. At Ship Harbor she shipped her fish to East Boston and then went to the Bay of Chaleurs for another fare. After she had secured about three-fourths of a load, as the fishing was not very brisk, she sailed down to the Magdalen Islands to try her luck there. She arrived Sunday, September 30th. She went Pleasant Bay under a gorgeous sunset of lemon and purple clouds. The Magdalen Islands form a sort of bay. Coffin Island, long and narrow, lies along the northern boundary. To the southeast is Entry Island big and rounded; at the north it grows narrower, and from the end of it a long reef, or hook, makes out; the southern boundary is another large island, called Amherst Island. This, too, has a big, rocky reef, which stretches out toward Entry Island. Between the two reefs is a narrow passage, not safe to try unless you have an experienced pilot at the wheel. Connecting Amherst Island with Coffin Island on the west is a long line of sandy or rocky islets, which, from their shape, are called Sugar Loaf. The entrance to this group is at the northeastern end. When the "Morning Star" came into Pleasant Bay. a fleet of one hundred and fifty sail lay anchored the whole length of Amherst Island. Many of the vessels were from Cape Ann and Cape Cod, but the greater part were from Maine. They were all anchored single, the usual arrangement, to prevent their running afoul if the anchors drag in a blow. The "Star" tacked across the bay and chose a berth second from the Amherst reef. As luck would have it, the "Juliet Tilden" was the first in the line. The boys of the "Morning Star" were very glad to go aboard the "Juliet" to get the home letters and news and swap a little sea gossip. The crew of the "Juliet" had had pretty good luck, so they intended to fish here for only a few days and then start for home. It was rather late in the season and storms were likely to brew right away. The crew of the "Morning Star" stayed aboard the "Juliet" until nearly midnight. As they went over the side of the "Juliet" into their yawl-boat, they looked off to the north and saw great black clouds gathering. Ned Brown called down to them, "Looks as if it might rain any minute. I guess we're going to have the biggest blow some of us have ever seen." Those were the last words from the "Juliet." In half an hour it was raining torrents and blowing a living gale from the north-northeast. The crew of the "Star" feared they might drag their anchors and go ashore, so they got under way and beat across; then they hove her short, put in three reefs, and Waited for the "Juliet" to get under way, which she did at once. They saw her fill away to the east toward the sandy hook. The "Star" filled away to the east on the same tack. As soon as she got headway enough to come in stays, they tacked ship again, and kept tacking for two mortal hours. Never had the schooner labored in the seas as she did that night. As soon as the first gray glimmer of dawn revealed their bearings, the "Star" crept up under Coffin Island and anchored. The waves were already mast-head high. They could see the rest of the fleet anchoring in the lee of the island, which broke the edge of the sea. About nine o'clock Monday morning they told the cook to go below and get breakfast. He came up directly, thoroughly frightened, and said he could not keep the pots and pans on the galley stove. As the captain was afraid of fire, he told him to batten down the hatch and leave everything snug below ship. All this time the gale kept growing. Ferdinand Devereux, who was one of the crew, said he had sailed south many years, but he had never met any hurricane that came up to this. They threw out life lines about the cabin and lashed themselves to them. From nine o'clock Monday morning till noon on Wednesday they did not have a thing to eat or drink. At one time it was necessary to take axes and stave in the bulwarks to let the water run off and ease the vessel or it would have been buried by the waves swamping it. It was a fearful sight to look up and see one of those great green combers towering mountain high above and the next moment to feel it break over them and try to dash the old "Star" to the bottom of the bay. Wednesday noon the wind went down as quickly as it came up on Sunday night. The sea was beautiful and serene. All the fleet got under way and made sail out of the bay to some islands off to the eastward of Entry Island, to finish up their fare, as they were only three-fourths full of fish. Now a strange thing happened. Explain it who can. All the rest of the hundred and fifty sail went to the eastward, supposing the "Juliet" was with them. The "Star" sailed out of the harbor at the same time, but when the others took the tack east they tacked due south. No one remembered who was at the wheel. Not a word was spoken. They just went along the east coast of Entry Island down south of Amherst. The crew always thought God's hand was on the tiller. They went under the lee of Amherst Island, to put a reef in their mainsail. It was about dusk, when Bill Eaton and a Thombs boy, both about fourteen years old, were fooling with the ship's spy-glass. One of them shouted, "There's a vessel wrecked on that reef." The other boy snatched away the glass and looked through it. "By gum, it's the 'Juliet Tilden'!" By this time it was too dark to make sure. They lowered their yawl boat, but could not get near the reef and the water roared so that they could hear nothing from the wreck. A man on the beach, some distance to the westward, told them at dawn to go to a certain small port, where they could find a good pilot to take them through the dangerous passage between the two islands to the spot where the vessel lay. The storm had been so great that the island folk had not been able to get off to help the wrecked sailors. All night long the watch saw lanterns moving along the beach. Early the next morning they took the pilot aboard the "Star," and he steered them inside the reef, where, sure enough, was the "Juliet," with her hull in the air and her broken mast buried in the sand, exactly as Mrs. Clark had seen it in her dream two months before. They lay off Harbor Lebar nine days and in that time picked up the battered bodies of the Castine boys, the flower of young manhood. Some were changed beyond all recognition by the cruel buffeting of the sea. They found poor Perk Hutchins lashed to the cabin, but the pounding of the sea had very nearly worn through the strands of a brand-new cable. Captain Sylvester was found lying face down in his oilskin helmet, which was full of blood, and both eyeballs were resting on his cheeks. Ed Clark was apparently the last to leave the vessel and was found under the upturned yawl-boat. The government had appointed a man at Pictou to look out for wrecked sailors. He and the Catholic priest, as well as the minister of the Church of England, were very kind and helpful. The houses on Amherst Island are built very low posted, a case of preparedness against the fearful gales of that region. In one of those little low houses, ten rough timbered hemlock coffins were lying in a row waiting for the burial service. The priest allowed them to be buried on the edge of the Catholic cemetery, which was much more convenient if any of the bodies were to be taken up later and shipped to Maine. They telegraphed from Pictou the news of the disaster to Castine. They remained a few days longer hoping to find Will Clark's body, which was not found till three weeks later, in a ravine up among the Sugar Loaf Islands. Ned Brown looked the most natural of them all. He had a sweet smile about his mouth, just as he often looked when he was thinking about Minetta. They brought what treasures they could find for the families — a knife, or a ring, or a watch. In Ned's pocket was found a little silver locket, which he had bought in Halifax to take home to Minetta. *

* *

The old Castine House had a beautiful stairway. It was the envy of all the townsfolk. Its reputation was known around the State, and people would go to the tavern just to see the old stairs. It was much like those in the celebrated Salem houses. Minetta was slowly descending the stairs with a big bunch of pink asters in her hand, which she was going to put on the desk in the office. Just then two travelling men came in. One of them said to the other, "I've been over to the telegraph office to send a telegram. The operator had just received a message from a man on board the 'Morning Star' telling of the awful wreck of the 'Juliet Tilden.'" Minetta dropped her asters all along the stairs. She ran up to the stranger, took him by the shoulder, sort of shook him and said, "Was Ned Brown saved?" The man not realizing what it all meant to her said, "Not a soul on board lived to tell the story." A great flood of color surged up to Minetta's cheeks then she went white as a sheet, and in a moment more was lying, a little crumpled heap, at the stranger's feet. She was carried to her bed and did not leave it for two weeks; and she would not then have done so. had she not heard that while she was lying heart-broken, caring for nothing in this world, Ethel Snowman's little baby was born prematurely the night they told her the news of her husband's death. Perhaps it was the best thing for Minetta, because it roused her from her stupor of despair. Wrapped in each other's arms the two young girls poured out their grief. From that time Minetta took almost as much care of the baby as did Ethel. Minetta became more and more subdued. She looked frail and delicate. She loved to climb around the rocks at Dice's Head. The neighbors said they often came across her sitting on the beach looking out to sea, her big violet eyes full of unshed tears. About five years after, Captain Hodsdon had a good chance to sell his hotel to a mining man, who paid him a fancy price, and with his daughters he moved out of town. Mrs. Juliet Tilden, for whom the schooner had been named, had never been strong and the constant terror under which she suffered while her husband was imprisoned during the Rebellion, had weakened her constitution. Now, under the weight of this fresh disaster to the schooner and the gloom that enshrouded the whole town, she faded away, like a beautiful flower crushed by a ruthless heel. Under cover of the beautiful serenity of the town lie these griefs hidden in the hearts that never forget. If one probes deep enough, he will discover the unhealed wound in the heart of many a maid, wife, or mother. Oh, these mothers by the sea! Their tear-washed eyes and thin white hands clasped in prayer attest the tragedy of their lives. They hate the sea, and yet they love the sea and cannot live without it. |