XIV

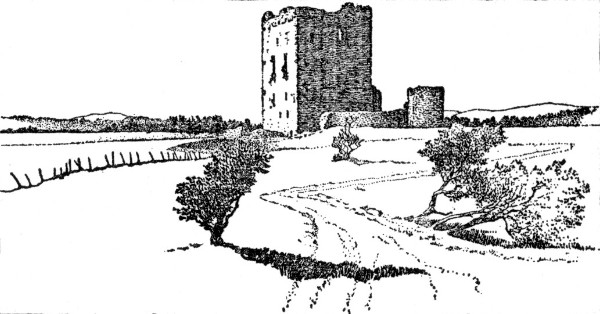

A GLIMPSE OF GALLOWAY  A Stone-breaker WHAT I saw of Galloway was mostly confined to its far end, where I spent some days in the little sea port town of Stranraer and its neighborhood. The attraction that drew me thither was in part a certain charm that literature has given to Galloway, but more a desire to see that portion of the district known as "The Rhinns." There was a mystic spell in this name which held suggestions of strange and highly picturesque landscape, and of native dwellers whose ways would be peculiarly primitive and interesting. But, after all, "Rhinns" is simply equivalent to the English word prongs, and a glance at the map reveals its significance, for the land projects seaward to north and south like the clumsy horns of some great beast. These Rhinns of Galloway are also called the Galloway Highlands, a name which for a stranger has a more definite meaning than the other, even if decidedly less fascinating. The scenery, however, is but a dwarfed imitation of the Scotch Highlands of the north, and is only worthy the title when comparison is made with the general low flatness of the rest of the Galloway country. The upheaval is never really lofty, rugged, or in any way striking, and indeed attains to nothing more than big, rounded swells. The grass-fields, pastures, ploughed lands, and the patches of woodland sweep away gently over the hilltops and down into the valleys, and, with the farmhouses, give the region an aspect of pleasant fertility. On a long tramp over the Rhinns, that occupied nearly the whole of a summer day, I learned that the farmers were far from satisfied, in spite of the seemingly prosperous cultivation of the country. They complained because prices were low, and because a certain ogre of a landlord dealt hardly with them, and stripped their holdings of the best cattle to satisfy his claims. "I kenned him," said one man, "when he hadna ane ha'penny to rub against anither. But he hae plenty noo. Hoo he gat his wealth I canna say, though 'tis tell't 'twas through a brither who robbed a bank in America. This brither was caught and pit in prison, but he had secretit the money, and when he was lat oot, he gat it and cam' hame, and he took to drink, and ane day jumped oot a twa-story window and was killed. Aifter that, the mon that's the landlord noo seemed to be sudden rich, and since then he hae bought a' the farmlands that coom in the market. But I'm no thinkin' his brither, gin he stole as they say, wad hae been lat loose if he hadna gi'en up the treasure he'd ta'en. The Yankees are too clever for that, are they not, noo?" I had not the assurance he showed as to the cuteness of my countrymen in such matters, and had to confess that some of our rascals have a good deal easier time than they deserve, and that we were in the habit of dealing less severely with the gentlemanly lawbreaker who, while in the employ of a bank, takes tens or hundreds of thousands, than with the petty thief whose methods are more vulgar, and whose stealings may amount to only a few dollars. The farmer whose remarks I have reported had fallen in with me on the road, and we had been trudging along in company, but now we came to the lane which turned aside to his home, and we parted. A little farther on I overtook half a dozen children playing horse. They had twigs for whips, and gay-colored worsted reins which they said they had knit themselves.  The Postman We got acquainted and kept on together for a mile or two. Sometimes they ran, sometimes walked, and sometimes stopped to make forays into the neighboring hedges or woodlands. They gathered flowers, and they watched the birds, and whenever a songster flew up from the clumps of furze and hawthorn growing on the roadside banks, they hastened to see if they could find a nest. Once they called me to them, and reaching into a cranny among the leaves and brambles of the hedgerow, took out an egg and a naked little bird for my delectation. I begged them to restore these treasures, and asked how they happened to find them. But they said, "Oh, we kenned that nest before." I had noticed that the fields seemed very vacant, and I mentioned this to the children. They, however, declared it was not so always, and I should wait till harvest. Then all the Irish came over from their home country to help, and the farmlands were nearly as busy as the town. "Are you all Scotch?" I queried. "Ay, we are, sir!" they responded. "And do you not wish you were Irish?" "No!" said they, with emphasis, "we would die firrust!" I suppose they had no idea how close was their racial relationship. For many miles after leaving Stranraer I was on a road that kept along the heights, but at length I descended by a side way to the sea, and followed the windings of the shore northerly. At one point I sat down and rested while I chatted with a white-haired laborer breaking stone by the roadside. Again, I paused to speak with a boy who lay in the grass on the open, seaward side of the highway watching a group of cows pasturing on the patches of unfenced grassland next the pebbly beach. He said he brought the cows there daily from the farm three miles distant. The afternoon was waning when I finally began to retrace my steps. Earlier, the sky had been clouded and threatening, but as I rambled back to the town the sun came out pleasantly warm, the haze in the air cleared, and I could see the green, hedgerowed hills beyond the bay. On another day I went by train across the Rhinns to Port Patrick. From there the Irish coast is only a score of miles distant, and Port Patrick used to be the landing point for vessels from Larne and Belfast. Half a million pounds were at one rime expended on the harbor, but the situation is too exposed, and the billows wrecked the great walls of masonry and tore apart the huge blocks of stone, even though they were bolted together with stout sinews of iron. At the same time the waves heaved many big boulders into the harbor entrance that shut out all but the smaller craft, and now you find the ruined masonry abandoned to the will of the sea. The place itself is a sleepy little village in a ravine that opens back inland between two steep slopes. It was named after Ireland's patron saint, who here first set foot on Scottish soil. Tradition relates that he came, not as ordinary mortals would, in a boat, but skipped over the twenty miles of water at a single jump. The marks of his feet where he landed were formerly plainly imprinted in a rock on the borders of the harbor, but this rock was broken up when that futile and expensive attempt was made to improve the port. St. Patrick did not find the people as hospitably inclined toward him as the Irish. Indeed, some of the Galloway men were rude enough to cut off the visiting saint's head. This treatment so offended him that he determined to leave Scotland, and he took his head in his teeth and swam across to his beloved Ireland. Quite likely the details of his return to Erin may be mythical. Certainly no one at present residing in the port claims to have witnessed the exploit, in spite of the fact that the inhabitants of the region live to a very great age. One of the stories illustrative of Galloway longevity is this: — "A stranger found a man of over threescore years and ten weeping by the roadside. He inquired the cause of this lamentation, and the old man said his father had just chastised him for throwing stones at his grandfather." After an hour or two by the shore, I followed a road up the hollow and on through a wood where the ground was sprinkled everywhere with bluebell clusters. Beyond the wood lay open hilltops, over which I went northward up and down the gloomy slopes for a long distance. It was a "coorse" day, as the Scotch say — the sky overcast with sullen clouds, and a chilly wind blowing. There was almost no protection on the uplands, for they were nearly bare of trees, and even hedgerows were infrequent. The crests of the hills were often wide wastes of heather and thorny whins, but lower lay broad farm fields. The cottages and farmhouses were far apart, and they so rarely had the softening touch of trees or shrubbery near them that they made the region look doubly lonely and desolate. Most of the time I had no company save that of the curlews and peesweeps, with their wild squeaks and screams, and I was heartily glad presently to meet a postman coming out from a farmyard gate. He was going in my direction, and I accelerated my speed to keep pace with him. A canvas bag containing the mail hung at his side, and he carried a rubber cape on his arm ready for use in case it rained. He had a long daily circuit to make, and said he walked a hundred miles a week. When we parted he went off by a path over the moorlands, and a little later I turned back toward Port Patrick, where I took the train for Stranraer. I stayed while in Stranraer at an unusually pleasant and homelike temperance hotel. Mrs. Bruce, the good old lady who kept the house, was very kind and motherly, and I liked nothing better of an evening than to sit and talk with her in her clean little kitchen. She did not have a very high opinion of Stranraer. In fact, she did not hesitate to say that she believed it was the most drunken place in Scotland. The police court had no end of cases of intoxication to deal with, especially on Monday mornings, when the tipplers had to answer for their Saturday night carousing. Worst of all, the provost (mayor) himself was a man who was boozing most of the time, and not infrequently had to be locked in his room while the liquor craze was on. Stranraer was a resort for all sorts of people, and in summer they came in crowds. Mostly they were Irish, arriving from their native isle by the steamship line which makes this its haven, or they were Scotch town-folk down from Ayr and Glasgow on a holiday. Mrs. Bruce liked the Irish best. They were sure to be pleasant-spoken and courteous, while the Scotch were at times rude and troublesome. My landlady formerly lived several miles from the town, out in the country, and there she for a long period lodged the ministers of the local church. She had a succession of six in her home, all young and all good enough in their way; but near acquaintance and knowledge of them had made it impossible for her to feel the veneration toward the cloth which she had been brought up to think was its due. Her previous intuitions were that a minister had something of the divine about him, and that there was a gulf fixed between him and ordinary folk. But of these six young men only one was at all consecrated to his work. With the others it was just a trade. They preached for a living, and she was afraid that was the case with nearly all ministers. She thought, too, that many of them did not thoroughly believe, or, at least, had little care one way or the other, about the doctrine which they preached. These six ministers who had been in her home were simply fun-loving young men, very human in their likes and dislikes, their faults and foibles; and, except for one, if they had happened to take up some other calling, it would have been all the same to them. I was not a little regretful when the time came to leave my Stranmer hotel, yet the pleasantest memory is of the parting. I had a long railroad journey before me, and at the last moment it occurred to the landlady and her daughter that I ought to take along a lunch. This they hastened to put up, and they would take no pay, but bestowed it on me and saw me started away with as much apparent solicitude as if I had been a near relative.  Woodland Hyacinths My last sight of the land of heather was from a little place called Gilsland, eighteen miles east of Carlisle. From the Gilsland railway station I tramped off over the hills in search of a portion of the old Roman wall said to be in existence there — the wall that was built across the north of England to keep out the Scots and Picts. I found what I sought on a grazing upland where the peaceful sheep were feeding, as if the scene had always been pastorally quiet and its ancient martial aspect a fable. But the appearance of Scotland was everywhere different in the days of the Romans. There was little cultivated land and smooth pasturage. On the hills were vast forests of giant oaks, and the swampy valleys were overgrown with thickets of birch, alder, and hazel. Deer, wolves, and wild cats abounded. It was a difficult country to conquer, and the Roman troops were incessantly engaged in warfare with the wild northern tribes. Nor did they ever succeed in permanently subduing them, and when they withdrew after occupying Britain for three and one half centuries, the people of the north were unchanged in either language or habits. A wall, to serve as a line of defence against the marauding Scotch, was begun about the year 120 by the emperor Hadrian. At first it was only an embankment of earth. When finished it stretched across the country for seventy miles, from the sea near Newcastle on the east, to the Solway Firth on the west. Soon after its completion the Roman frontier was pushed onward some fifty or more miles, and another wall was built, from the Firth of Forth at Edinburgh to the Clyde at Dumbarton. This marked the extreme northern limit of the empire. The strip between the two walls included most of the Scotch Lowlands; but it did not long remain in undisputed Roman possession, and presently the southern wall was again the defensive border line. When Severus came to Britain, he replaced the earth rampart with a wall of stone eight feet thick and twelve feet high. Along its course he established eighteen military stations garrisoned by cohorts of Roman soldiers, and at intervals of a mile were forts containing one hundred men each, while between each pair of forts were four watchtowers. Toward the close of the fourth century Roman dominion was reasserted over the Scotch lowlands, but the territory was shortly lost again, and a little later the Romans finally abandoned Britain. Of the huge line of fortifications erected by the old Roman emperors surprisingly little remains, and even when the remnants are best preserved, as at Gilsland, they are not at all conspicuous. Here had been one of the old forts, and I had expected to see some massive ruins; but the reality was hardly more than an ordinary stone fence, and it was rarely so high that I could not overlook it. Beyond a narrow area on this hilltop the old-time upheavals of earth and stone ceased altogether, and the fragments to be found anywhere from coast to coast are few and insignificant. But, though to the eye the ruins were not at all imposing, when I recalled their age and associations, to have seen them seemed a notable experience. They furnished, too, an impressive example of time's power to level and disintegrate, and of the constant efforts of the elements to wipe out everything that lifts itself above the general level, though man, too, in this instance, has had much to do with the devastation.  The Wall of Severus Now I took leave of bonnie Scotland and journeyed southward into England, a section more beautiful, perhaps, to the eye, but certainly not one which appeals more forcibly to the imagination. I doubt if any land has the fortune to be as widely loved by those not native to its soil as this country of the heather. Its glens and hills, its woods and shrubby dens, its bracken slopes and moorland heights, its noisy streams and its mountain-girded lochs have won the affection of the whole English-speaking race. Then there is its past, its days of heroism and romance, that live for us in history and song, and, more than all, in the magic pages of Sir Walter Scott. Finally, Scotland is the home of one of the most hardy, thrifty, brave, and warm-hearted races in the world.  A Castle of the Black Douglas |

Web and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio

1999-2008

(Return to Web Text-ures)