| Web

and Book

design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

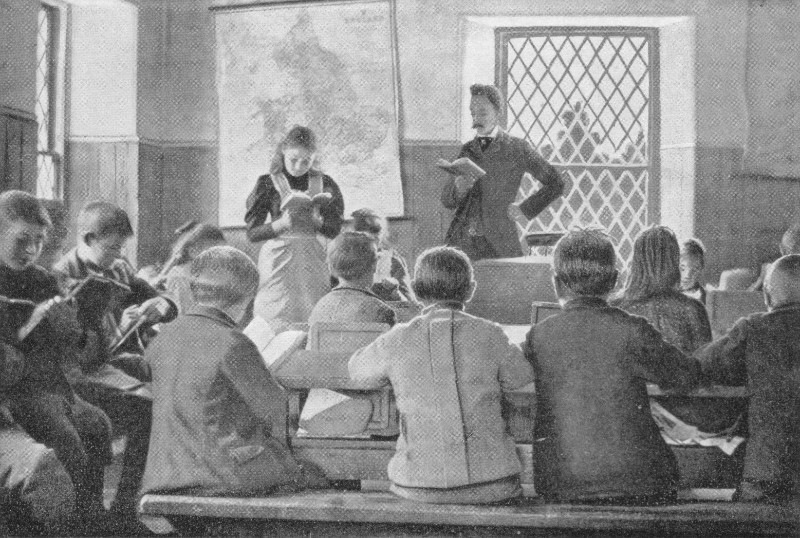

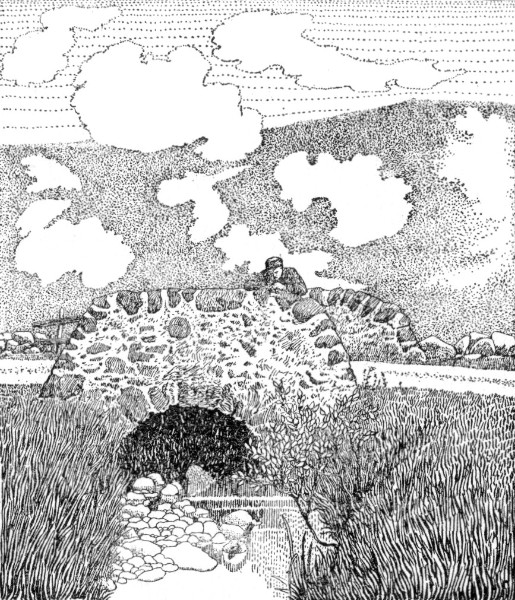

XI

A COUNTRY SCHOOL  A Bird's-nest in the Hedge I HAD wandered into a high land glen girdled about with wild heather-clad ridges. In the depths of the valley a little river looped its way along, helping to make fertile the bordering farm lands, and the heart of the glen with its emerald meadows and the silvery glint of the stream was pleasant to look on; but the region, as a whole, was too treeless to attract, while the brown, undulating hills were so sombre as to be almost forbidding. It is true the district was not without a certain rude kind of beauty, and the hills had about them a good deal of elemental grandeur, yet to live the year through in their big, barren presence I fancied must be sobering and oppressive. Probably those born among them did not share this feeling, for the glen did not lack inhabitants. There were farmhouses and now and then the humble dwelling of a cotter or a laborer. One would expect in a region so lonely that the homes would gather in clusters for companionship; but it was not so here, and neighbors were half a mile or more apart. Even the schoolhouse, midway on the long valley highway, stood solitary like the rest, and was almost as much isolated from neighbors as it was from the great world that lay beyond the encompassing hills. I entered the glen wholly intent on pushing up the valley and enjoying the unfolding of the landscape which took on a new aspect with every turn of the road. But when I reached the schoolhouse I paused. What kind of a school would be kept here, I asked; what sort of a person would the teacher be, and what the nature of the scholars? I turned into the school-yard. It was a long, narrow yard surrounded by a high stone wall. There was some greenness near the road, but the grass had been much trampled, and the playground grew dustier and more gritty as I walked down it, till near the school building naught was left but bare earth. At that end of the yard stood a pump, around which the ground was hardened and worn more than anywhere else. This seemed to attest the great fascination water has for children, both for internal thirst and external sport. One would think there were lingering impulses in them descended from some far-back fishy ancestors. The schoolhouse had masonry walls spatterdashed with a mixture of whitewash and gravel, and it had diamond-paned windows that gave it something the look of a tiny church. But this churchly illusion was lost in the near view, for then I saw that the master's dwelling was joined to it at the back, and that a gate in a rear corner of the playground opened on a path leading to his house door. It was as yet too early in the morning for school to begin, and at first I thought the place was deserted; but when I looked inside, I discerned with some difficulty a little girl at the far end of the schoolroom half concealed in the dust raised by a vigorous plying of the broom. She had paused when she saw a stranger in the doorway. I spoke with her, and learned that she was the master's daughter, and then I asked to see her father. She said he was down in the meadow by the river, and without more ado dropped her broom and trotted away, yelling, to find him. I am afraid this little earthquake of a daughter chasing and calling for him so vociferously scared the man, for it was barely a minute before he came running breathless up the hill back of the schoolhouse and jumped through a gap in the wall as excitedly as if he had been going to a fire. I thought he might be disappointed when he found only me there, but his haste apparently only meant cordiality. Probably a visitor was a rarity to be made the most of. The master was a little man, rather above forty years of age, with a quick and nervous manner that was the more pronounced because of his anxiety to do the honors of host with credit: and no one could have been kinder or have done more to make my stay pleasant. By the time I had done introducing myself the scholars began to arrive, and presently the master put aside his broad-brimmed gray hat and called his pupils who were at their games in the dusty yard by shouting from the doorway, "Come away, then!" a command which he supplemented with a shrill whistle. The schoolroom seemed very small and crowded when all the scholars were in. It was lighted by four large windows. A continuous desk ran the whole length of the west wall, and turning the corner extended as far as the master's platform. This desk was right against the sides of the room like a long shelf, and the children who sat on the backless bench that paralleled it faced away from the rest of the school toward the wall. To get to their seats on this bench the children usually either stepped over or sat down and whirled. The boys were some of them very acrobatic in getting their heels over the obstructing bench. On the other hand, some of the girls went to the opposite extreme and waddled mildly over on their knees. Most of the schoolroom floor space was filled with a row of long movable desks, each with an accompanying bench. The scholars on the rear seat had nothing but vacancy to lean against, but the others had a sharp-cornered desk at their backs. At the far end of the room sat the babies of the school — half a dozen little innocents on a bench snug against the wall with a row of hooks above hung full of hats and cloaks. What weary times those little martyrs must have, I thought, sitting there with heels dangling in air through the long school hours. I could see but one alleviation — the bench was against the wall, and if its occupants went to sleep and tumbled off, they could not fall backwards. None of the school furniture had ever been painted, and the white plaster of the walls had never been papered. The only wall decorations were two large squares of blackboard suspended from nails, several good-sized maps, and a tonic-sol-fa chart. The room was heated by a small fireplace in which peat was burned. If they ever had a touch of New England weather in their winters, the children were bound to suffer. But the master considered the schoolhouse on the whole a very good one — certainly it was an improvement on the one in which he got his own early schooling. That had a floor of dirt, and he described the fascinated interest with which he used to watch the angleworms boring up out of the earth in school-time. I had been somewhat disturbed when I went inside the schoolhouse with the master, following the children whom he had summoned from their games in the yard, to find that the schoolroom was entirely chairless. There was not even a chair for the teacher, and I was preparing to sit on one of the benches with the scholars when he stopped me, and sent a boy to the house for a chair. I was curious to learn what he himself did for a seat. So far as I observed, he made his desk on the platform serve. It was a boxy little affair, with a tall bottle of ink and a pile of copybooks on the floor underneath. The master had several different ways of sitting down on this desk, and sometimes he half lay down on it. He was entirely unconventional. The first thing the teacher did, after I had my chair and the scholars were in their places, was to say in his sudden, explosive way, "Stand, then!" The children stood and repeated the Lord's prayer in unison, and at the close the master said, "Sit, then." Usually the session began with the singing of a hymn, but the dominie explained that as several of his best singers were absent, he did not feel like having_ the singing before a stranger. At the conclusion of the prayer he asked several scholars to repeat certain of the commandments, and tell what was meant by them, and the whole hour from nine to ten was spent in these and other exercises of a distinctly religious character. The master said it was the hour of "the conscience clause." Attendance was not compulsory, and any parents who chose could keep their children out till it was over. As a matter of fact, this was a privilege rarely taken advantage of. On the first four days of the week much of the hour was spent in Bible reading, but on Friday the time was devoted to studying the Shorter Westminster Catechism. At ten o'clock the master called off the thirty-six names he had on his roll, and then he had his oldest class read Sir Walter Scott's poem, "The Battle of Flodden." This class of seniors, which the master spoke of as "The Sixth Standard" had sat, while reciting, in the corner next the platform, with their backs against the continuous wall-desk. The reading was noteworthy chiefly for its remarkable lack of expression. Every child kept the same key of voice right through, and only used punctuation marks to catch breath. One would think the poem itself conveyed no meaning to their minds, and that they were simply reciting a list of words. After the reading the master put some questions to the class, beginning with, "Where is Flodden?" If the ones questioned hesitated, he hastened their wits by exclaiming, "Come on, now!"  The School at Work Besides geographical and historical questions he asked meanings of words, had the scholars parse and spell, and sometimes called for the Latin derivation of a word. When he had doubts as to whether the children were going to answer, he would give a partial reply himself, as, for instance, when he asked, "What is the meaning of volley?" — pause — "What is it, Jessie?" — anxious silence which the master breaks by saying, "a great many guns" — he lingered over every word in the hope that the girl would catch the cue — "going off at the same t — " "Time," says Jessie, quickly, and that passed for an answer. The scholars picked the final word of an answer off the master's tongue in that way again and again, and he would dwell on the first letter of the key-word just as long as he could if the response was still delayed, and lean forward in keen anxiety that the scholar should not force him to pronounce it all. Usually his efforts met with a prompt reward, and he could settle back in relief and in pride over his pupils' ability. The recitation was brought to an end by the following explanation from the schoolmaster: "King James of Scotland," said he, "fought this battle of Flodden just to please the Queen of France, and he lost his life in it — lost his life to please a woman! There's many a man more has lost his life that same way, hey?" Now the teacher dismissed the senior class and then he called out, "Come up, the Fifth Standard." The Fifths, having seated themselves in the vacated corner, read a prose piece about the Chinese city of Pekin in the same meaningless monotone that the preceding class had used. One feature of the lesson was a description of "a scribe in the street writing a letter for a love-sick swain," and when he finished writing it, he had read it aloud to the bystanders. "You wouldna care to hae your love-letters read that way!" was the master's comment to his class. The children smiled as if they thought not. The scholars who were not in the class reciting talked together, walked around the room on errands of business or pleasure, and were. sometimes mischievous and heedlessly noisy. So great was the pandemonium that the master had me move my chair closer to the reciting class that I might hear them better through the din. When there came a sound of wheels from the highway every one looked out, and word was passed around as to who it was that had driven by. In the midst of the session the sanitary inspector called. He is a government official who comes around once or twice a year, calling at every house to see whether sinks and drains and other details about buildings that affect health are all right. He looks through the rooms upstairs and downstairs, and if people do not keep their dwellings in repair, or crowd too many persons in too few rooms, or if they have stagnant pools close about the house, he tells them to alter things. The benefits of such oversight when the investigation is competent and faithful are obvious, and it would seem as if the same sort of supervision in the interests of health might well be introduced in our own country. The inspector's only comment on the schoolhouse was that it leaked wind badly. Another interruption was caused by the arrival of a cart from down the valley, that carried cakes and sweets. One of the girls immediately rose and made a tour of the schoolroom, collecting coppers from those who wanted some of the toothsome wares they knew were to be had from the pedler waiting in the roadway. The girl acting as agent for her companions went out, did the trading with the man who drove the cart, and then hastened back to distribute the goods she had bought through the schoolroom. All this made no appreciable interruption in the school routine, and was plainly prearranged and understood by all parties. The morning session of school was very long. The hour allowed for dinner did not begin till one o'clock, and when the master about twelve let the children out to play, I signified my intention to leave. But he would not hear to it unless I came to the house first and had a bottle of ale with him. I agreed, as far as going to the house was concerned, but the ale he drank himself. In the fear that I had refused because ale was not strong enough, he proposed to set out whiskey for me, and when that, too, failed to prove a basis of good fellowship, he asked his wife to bring a glass of milk and a plate of biscuit and cheese. We chatted indoors for a time, and then he took me into his garden and talked of its various flowers, shrubs, and vegetables, and the richness of the heather honey that his bees made. When at length I said "good-by." I left him with real regret, his hospitality was so hearty, and he was so anxious all through to make my stay pleasant. He was an easy-going little man, and his teaching was nothing to boast of. Indeed, the school had the air of a rather disorderly family, and the master seemed more like an older child in control than the middle-aged man that he was, making teaching in this lonely Highland valley his life-work. Still, whatever the teacher's faults, his heart was right, and there was something about the school and its ways in their unconventional simplicity that attracted one. I shall probably never see that out-of-the-way glen again, nor ever hear from it, but I shall never forget the kindly master and his little white schoolhouse, with the big brown hills frowning and glooming down on it with every passing cloud-shadow.  "A Wee Brig ower a Burnie" |