| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

A Journey to the Tea Countries of China Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

XIII.

Woo-e-shan

— Ascent of the hill — Arrive at a Buddhist temple —

Description of the temple and the scenery — Strange rocks — My

reception — Our dinner and its ceremonies — An interesting

conversation — An evening stroll — Formation of the rocks —

Soil — View from the top of Woo-e-shan — A priest's grave — A

view by moonlight — Chinese wine — Cultivation of the tea-shrub —

Chains and monkeys used in gathering it — Tea-merchants —

Happiness and contentment of the peasantry.

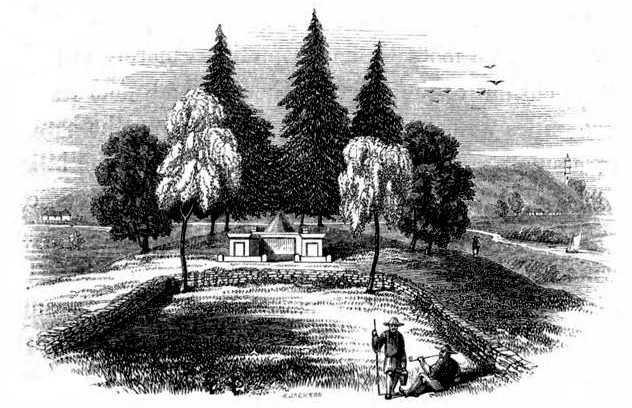

AS soon as I was fairly out of the suburbs of Tsong-gan-hien I had my first glimpse of the far-famed Woo-e-shan. It stands in the midst of the plain which I have noticed in the previous chapter, and is a collection of little hills, none of which appear to be more than a thousand feet high. They have a singular appearance. Their faces are nearly all perpendicular rock. It appears as if they had been thrown up by some great convulsion of nature to a certain height, and as if some other force had then drawn the tops of the whole mass slightly backwards, breaking it up into a thousand hills. By some agency of this kind it might have assumed the strange forms which were now before me. Woo-e-shan is considered by the Chinese to be one of the most wonderful, as well as one of the most sacred, spots in the empire. One of their manuscripts, quoted by Mr. Ball, thus describes it: "Of all the mountains of Fokien those of Woo-e are the finest, and its water the best. They are awfully high and rugged, surrounded by water, and seem as if excavated by spirits; nothing more wonderful can be seen. From the dynasty of Csin and Han, down to the present time, a succession of hermits and priests, of the sects of Tao-cze and Fo, have here risen up like the clouds of the air and the grass of the field, too numerous to enumerate. Its chief renown, however, is derived from its productions, and of these tea is the most celebrated." I stood for some time on a point of rising ground midway between Tsong-gan-hien and Woo-e-shan, and surveyed the strange scene which lay before me. I had expected to see a wonderful sight when I reached this place, but I must confess the scene far surpassed any ideas I had formed respecting it. There had been no exaggeration in the description given by the Jesuits, or in the writings of the Chinese, excepting as to the height of the hills. They are not "awfully high;" indeed, they are lower than most of the hills in this part of the country, and far below the height of the mountain ranges which I had just crossed. The men who were with me pointed to the spot with great pride, and said, "Look, that is Woo-e-shan! have you anything in your country to be compared with it?" The day was fine, and the sun's rays being very powerful I had taken up my position under the spreading branches of a large camphor-tree which grew by the roadside. Here I could willingly have remained until night had shut out the scene from my view, but my chair-bearers, who were now near the end of their journey, intimated that they were ready to proceed, so we went onwards. The distance from Tsong-gan-hien to Woo-e-shan is only about 40 or 50 le. This is, however, only to the bottom of the hills, and we intended to take up our quarters in one of the principal temples near the top. The distance we had to travel was therefore much greater than this. When we arrived at the foot of the hill we inquired our way to the temple. "Which temple do you wish to go to?" was the answer; "there are nearly a thousand temples on Woo-e-shan." Sing-Hoo explained that we were unacquainted with the names of the different temples, but our object was to reach one of the largest. We were directed, at last, to the foot of some perpendicular rocks. When we reached the spot I expected to get a glimpse of the temple we were in search of somewhere on the hill side above us, but there was nothing of the kind. A small footpath, cut out of the rock, and leading over almost inaccessible places, was all I could see. It was now necessary for me to get out of my chair, and to scramble up the pathway — often on my hands and knees. Several times the coolies stopped, and declared that it was impossible to get the chair any further. I pressed on, however, and they were obliged to scramble after me with it. It was now about two o'clock in the afternoon; there was scarcely a cloud in the sky, and the day was fearfully hot. As I climbed up the rugged steep, the perspiration streaming from every pore, I began to think of fever and ague, and all those ills which the traveller is subject to in this unhealthy climate. We reached the top of the hill at last, and our eyes were gladdened with the sight of a rich luxuriant spot, which I knew at once to be near a Buddhist temple. Being a considerable way in advance of my chair-bearers and coolies, I sat down under the shade of a tree to rest and get cool before I entered its sacred precincts. In a few minutes my people arrived with smiling countenances, for they had got a glimpse of the temple through the trees, and knew that rest and refreshment awaited them. The Buddhist priesthood seem always to have selected the most beautiful spots for the erection of their temples and dwellings. Many of these places owe their chief beauty to the protection and cultivation of trees. The wood near a Buddhist temple in China is carefully protected, and hence a traveller can always distinguish their situation, even when some miles distant. In this respect these priests resemble the enlightened monks and abbots of the olden time, to whose taste and care we owe some of the richest and most beautiful sylvan scenery in Europe. The temple, or collection of temples, which we now approached, was situated on the sloping side of a small valley, or basin, on the top of Woo-e-shan, which seemed as if it had been scooped out for the purpose. At the bottom of this basin a small lake was seen glistening through the trees, and covered with the famous lien-wha, or Nelumbium — a plant held in high esteem and veneration by the Chinese, and always met with in the vicinity of Buddhist temples. All the ground from the lake to the temples was covered with the tea-shrub, which was evidently cultivated with great care, while on the opposite banks, facing the buildings, was a dense forest of trees and brushwood. On one side — that on which the temples were built — there were some strange rocks standing like huge monuments which had a peculiar and striking appearance. They stood near each other, and were each from 80 to 100 feet in height. These no doubt had attracted, by their strange appearance, the priests who first selected this place as a site for their temples. The high-priest had his house built at the base of one of these huge rocks, and to it we bent our steps. Ascending a flight of steps, and passing through a doorway, we found ourselves in front of the building. A little boy, who was amusing himself under the porch, ran off immediately and informed the priest that strangers had come to pay him a visit. Being very tired, I entered the reception hall, and sat down to wait his arrival. In a very short time the priest came in and received me with great politeness. Sing-Hoo now explained to him that I had determined to spend a day or two on Woo-e-shan, whose fame had reached even the far-distant country to which I belonged; and begged that we might be accommodated with food and lodgings during our stay. While the high-priest was listening to Sing-Hoo he drew out of his tobacco-pouch a small quantity of Chinese tobacco, rolled it for a moment between his finger and thumb, and then presented it to me to fill my pipe with. This practice is a common one amongst the inhabitants of these hills, and indicates, I suppose, that the person to whom it is presented is welcome. It was evidently kindly meant, so, taking it in the same kind spirit, I lighted my pipe and began to smoke. In the mean time our host led me into his best room, and, desiring me to take a seat, he called the boy, and ordered him to bring us some tea. And now I drank the fragrant herb, pure and unadulterated, on its native hills. It had never been half so grateful before, or I had never been so much in need of it; for I was hot, thirsty, and weary, after ascending the hill under a burning sun. The tea soon quenched my thirst and revived my spirits, and called to my mind the words of a Chinese author, who says, "Tea is exceedingly useful; cultivate it, and the benefit will be widely spread; drink it, and the animal spirits will be lively and clear." Although I can speak enough of the Chinese language to make myself understood in several districts of the country, I judged it prudent not to enter into a lengthened conversation with the priests at this temple. I left the talking part of the business to be done by my servant, who was quite competent to speak for us both. They were therefore told that I could not speak the language of the district, and that I came from a far country "beyond the great wall." The little boy whom I have already noticed now presented himself, and announced that dinner was on the table. The old priest bowed to me, and asked me to walk into the room in which the dinner was served. I did not fail to ask him to precede me, which of course he "couldn't think of doing," but followed me, and placed me at his left hand in the "seat of honour." Three other priests took their seats at the same table. One of them had a most unprepossessing appearance; his forehead was low, he had a bold and impudent-looking eye, and was badly marked with the smallpox. In short, he was one of those men that one would rather avoid than have anything to do with. The old high-priest was quite a different-looking man from his subordinate. He was about sixty years of age, and appeared to be very intelligent. His countenance was such as one likes to look upon; meekness, honesty, and truth were stamped unmistakeably upon it. Having seated ourselves at table, a cup of wine was poured out to each of us, and the old priest said, "Che-sue, che-sue" — Drink wine, drink wine. Each lifted up his cup, and brought it in contact with those of the others. As the cups touched we bowed to each other, and said, "Drink wine, drink wine." The chopsticks which were before each of us were now taken up, and dinner commenced. Our table was crowded with small basins, each containing a different article of food. I was surprised to see in one of them some small fish, for I had always understood that the Buddhist priesthood were prohibited from eating any kinds of animal food. The other dishes were all composed of vegetables. There were young bamboo shoots, cabbages of various kinds both fresh and pickled, turnips, beans, peas, and various other articles, served up in a manner which made them very palatable. Besides these there was a fungus of the mushroom tribe, which was really excellent. Some of these vegetables were prepared in such a manner as made it difficult to believe that they were really vegetables. All the dishes, however, were of this description, except the fish already noticed. Rice was also set before each of us, and formed the principal part of our dinner. While the meal was going on the priests continually pressed me to eat. They praised the different dishes, and, as they pointed them out, said, "Eat fish, eat cabbage," or, "eat rice," as the case might be. Not unfrequently their politeness, in my humble opinion, was carried rather too far; for they not only pointed out the dishes which they recommended, but plunged their own chopsticks into them, and drew to the surface such delicate morsels as they thought I should prefer, saying, "Eat this, eat this." This was far from agreeable, but I took it all as it was intended, and we were the best of friends. An interesting conversation was carried on during dinner between Sing-Hoo and the priests. Sing-Hoo had been a great traveller in his time, and gave them a good deal of information concerning many of the provinces both in the north and in the south, of which they knew little or nothing themselves. He told them of his visit to Pekin, described the Emperor, and proudly pointed to the livery he wore. This immediately stamped him, in their opinions, as a person of great importance. They expressed their opinions freely upon the natives of different provinces, and spoke of them as if they belonged to different nations, just as we would do of the natives of France, Holland, or Denmark. The Canton men they did not like; the Tartars were good — the Emperor was a Tartar. All the outside nations were bad, particularly the Kwei-tszes, a name signifying Devil's children, which they charitably apply to the nations of the western world. Having finished dinner, we rose from the table and returned to the hall. Warm water and a wet cloth were now set before each of us, to wash with after our meal. The Chinese always wash with warm water, both in summer and winter, and rarely use soap or any substance of a similar nature. Having washed my face and hands in the true Chinese style, I intimated my wish to go out and inspect the hills and temples in the neighbourhood. Calling Sing-Hoo to accompany me, we descended the flight of steps and took the path which led down to the lake at the bottom of the basin. On our way we visited several temples; none of them, however, seemed of any note, nor were they to be compared with those at Koo-shan near Foo-chow-foo. In truth the good priests seemed to pay more attention to the cultivation and manufacture of tea than to the rites of their peculiar faith. Everywhere in front of their dwellings I observed bamboo framework erected to support the sieves, which, when filled with leaves, are exposed to the sun and air. The priests and their servants were all busily employed in the manipulation of this valuable leaf. When we arrived at the lake it presented a fine appearance. The noble leaves of the nelumbium were seen rising above its surface, and gold and silver fish were sporting in the water below, while all around the scenery was grand and imposing. Leaving the lake we followed the path which seemed to lead us to some perpendicular rocks. In the distance we could see no egress from the basin, but as we got nearer a chasm was visible by which the huge rock was parted, and through which flowed a little stream with a pathway by its side. It seemed, indeed, as if the stream had gradually worn down the rock and formed this passage for itself, which was not more than six or eight feet in width. These rocks consist of clay slate, in which occur, embedded in the form of beds or dykes, great masses of quartz rock, while granite of a deep black colour, owing to the mica, which is of a fine deep bluish-black, cuts through them in all directions. This granite forms the summit of most of the principal mountains in this part of the country. Resting on this clay slate are sandstone conglomerates, formed principally of angular masses of quartz held together by a calcareous basis, and alternating with these conglomerates there is a fine calcareous granular sandstone, in which beds of dolomitic limestone occur. The geologist will thus see what a strange mixture forms part of these huge rocks of Woo-e-shan, and will be able to draw his own conclusions. Specimens of these rocks were brought away by me and submitted both to Dr. Falconer of Calcutta and Dr. Jameson of Saharunpore, who are well known as excellent geologists. The soil of these tea-lands consists of a brownish-yellow adhesive clay. This clay, when minutely examined, is found to consist of particles of the rocks and of vegetable matter. It has always a very considerable portion of the latter in its composition in those lands which are very productive and where the tea-shrub thrives best. Threading our way onward through the chasm, with the rocks standing high on each side and dripping with water, we soon got into the open country again. After having examined the rocks and soil, my object was to get a good view of the surrounding country, and I therefore made my way to the heights above the temples. When I reached the summit the view I obtained was well worth all my toil. Around and below me on every side were the rugged rocks of Woo-e-shan, while numerous fertile spots in glens and on hill sides were seen dotted over with the tea-shrub. Being on one of the highest points I had a good view of the rich valleys in which the towns of Tsong-gan-hien and Tsin-tsun stand. Far away to the northward the chain of the Bohea mountains were seen stretching from east to west as far as the eye could reach, and apparently forming an impenetrable barrier between Fokien and the rich and populous province of Kiang-see. The sun was now setting behind the Bohea hills, and, as twilight is short in these regions, the last rays warned me that it would be prudent to get back to the vicinity of the temples near which I had taken up my quarters. On my way back I came upon a tomb in which nine priests had been interred. It was on the hill side, and seemed a fit resting-place for the remains of such men. It had evidently been a kind of natural cavern under the rock, with an opening in front. The bodies were placed in it, the arched rock was above them, and the front was built up with the same material. Thus entombed amongst their favourite hills, these bodies will remain until "the rocks shall be rent," at that day when the trumpet of the archangel shall sound, and the grave shall give up its dead. On a kind of flat terrace in front of this tomb I observed the names of each of its occupants, and the remains of incense-sticks which had been burning but a short time before, when the periodical visit to the tombs was paid. I was afterwards told by the high priest that there was still room for one more within the rocky cave. That one, he said, was himself; and the old man seemed to look forward to the time when he must be laid in his grave as not far distant. As I was now in the vicinity of the temples, and there was no longer any danger of my losing my way, I was in no hurry to go in-doors. The shades of evening gradually closed in, and it was night on Woo-e-shan. A solemn stillness reigned around, which was broken only by the occasional sound of a gong or bell in the temple, where some priest was engaged in his evening devotions. In the mean time the moon had risen, and the scene appeared, if possible, more striking than it had been in daylight. The strange rocks, as they reared their rugged forms high above the temples, partly in bright light and partly in deep shade, had a curious and unnatural appearance. On the opposite side the wood assumed a dark and dense appearance, and down in the bottom of the dell the little lake sparkled as if covered with gems. I sat down on a ledge of rock, and my eyes wandered over these remarkable objects. Was it a reality or a dream, or was I in some fairy land? The longer I looked the more indistinct the objects became, and fancy seemed inclined to convert the rocks and trees into strange living forms. In circumstances of this kind I like to let imagination roam uncontrolled, and if now and then I built a few castles in the air they were not very expensive and easily pulled down again. Sing-Hoo now came out to seek me, and to say that our evening meal was ready, and that the priests were waiting. When I went in I found the viands already served. We seated ourselves at the table, pledged each other in a cup of wine, and the meal went on in the same manner as the former one. Like most of my countrymen, I have a great dislike to the Chinese sam-shoo, a spirit somewhat like the Indian arrack, but distilled from rice. Indeed the kind commonly sold in the shops is little else than rank poison. The Woo-e-shan wine, however, was quite a different affair: it resembled some of the lighter French wines; was slightly acid, agreeable, and in no way intoxicating, unless when taken in immoderate quantities. I had no means of ascertaining whether it was made from the grape, or whether it was a kind of sam-shoo which had been prepared in a particular way, and greatly diluted with water. At all events it was a very agreeable accompaniment to a Chinese dinner. During our meal the conversation between Sing-Hoo and the priests turned upon the strange scenery of these hills, and the numerous temples which were scattered over them, many of which are built in the most inaccessible places. He informed them how delighted I had been with my walk during the afternoon, and how much I was struck with the strange scenery I had witnessed. Anything said in praise of these hills seemed to please the good priests greatly, and rendered them very communicative. They informed us that there were temples erected to Buddha on every hill and peak, and that in all they numbered no less than nine hundred and ninety-nine. The whole of the land on these hills seems to belong to the priests of the two sects already mentioned, but by far the largest portion belongs to the Buddhists. There are also some farms established for the supply of the court of Peking. They are called the imperial enclosures; but I suspect that they too are, to a certain extent, under the management and control of the priests. The tea-shrub is cultivated everywhere, and often in the most inaccessible situations, such as on the summits and ledges of precipitous rocks. Mr. Ball states1 that chains are said to be used in collecting the leaves of the shrubs growing in such places; and I have even heard it asserted (I forget whether by the Chinese or by others) that monkeys are employed for the same purpose, and in the following manner: — These animals, it seems, do not like work, and would not gather the leaves willingly; but when they are seen up amongst the rocks where the tea-bushes are growing, the Chinese throw stones at them; the monkeys get very angry, and commence breaking off the branches of the tea-shrubs, which they throw down at their assailants I should not like to assert that no tea is gathered on these hills by the agency of chains and monkeys, but I think it may be safely affirmed that the quantity procured in such ways is exceedingly small. The greatest quantity is grown on level spots on the hillsides, which have become enriched, to a certain extent, by the vegetable matter and other deposits which have been washed down by the rains from a higher elevation. Very little tea appeared to be cultivated on the more barren spots amongst the hills, and such ground is very plentiful on Woo-e-shan. Having been all day toiling amongst the hills, I retired to rest at an early hour. Sing-Hoo told me afterwards that he never closed his eyes during the night. It seems he did not like the appearance of the ill-looking priest; and having a strong prejudice against the Fokien men, he imagined an attempt might be made to rob or perhaps murder us during the night. No such fears disturbed my rest. I slept soundly until morning dawned, and when I awoke felt quite refreshed, and equal to the fatigues of another day. Calling for some water to be brought me, I indulged in a good wash, a luxury which I could only enjoy once in twenty-four hours. During my stay here I met a number of tea-merchants from Tsong-gan-hien, who had come up to buy tea from the priests. These men took up their quarters in the temples, or rather in the priests' houses adjoining, until they had completed their purchases. Coolies were then sent for, and the tea was conveyed to Tsong-gan-hien, there to be prepared and packed for the foreign markets. On the morning of the third day, having seen all that was most interesting in this part of the hills, I determined to change my quarters. As soon as breakfast was over I gave the old priest a present for his kindness, which, although small, seemed to raise me not a little in his esteem. The chair-bearers were then summoned, and we left the hospitable roof of the Buddhist priests to explore more distant parts of the hills. What roof was next to shelter me I had not the most remote idea. Our host followed me to the gateway, and made his adieus in Chinese style. As we threaded our way amongst the hills, I observed tea-gatherers busily employed on all the hill-sides where the plantations were. They seemed a happy and contented race; the joke and merry laugh were going round, and some of them were singing as gaily as the birds in the old trees about the temples.

1 Cultivation and Manufacture of Tea.  |