|

THE WISHING CARPET

My

rug lies under the candle-light,

Flame-red,

sea-blue, leaf-brown, gold-bright,

Born

of the shifting ancient sand

Of

a far-away desert land.

There

in Haroun al Raschid's day

A

carpet enchanted, their wise men say,

Was

woven for princes, in realms apart —

And

so is this rug of my heart!

Here

is a leaf like the heart of a rose,

And

here the shift in the pattern shows

How

another weft in the tireless loom

Set

the gold of the skies a-bloom.

Old

songs, old legends and ancient words

They

weave in the web as they pasture their herds

On

the barren slopes of a mountain height

In

the dusk of the lonely night.

Prayers

and memories and wordless dreams,

Changeful

shadows and lancet gleams, —

The

Eden Tree in its folding wall

Knows

them and guards them all.

To

Moussoul market the rug they brought

With

all its treasure of woven thought,

And

thus over half a world of sea

Came

the Wishing Rug to me.

|

XVII

THE

HERBALIST'S BREW

HOW

TOMASO, THE PHYSICIAN OF PADUA, FOUND A CURE FOR A WEARY SOUL

THERE

was thunder in the air, one summer day in King's Barton. Dame

Lavender, putting her drying herbs under cover, wondered anxiously

what Mary was doing. The moods of the royal lady in the castle

depended very much on the weather, and both of late had been

uncertain. Strong-willed, hot-tempered, ambitious and adventurous,

this Oueen had no traits that were suited to a quiet existence in the

country. Yet she would have been about as safe a person to have at

large as a wild-cat among harriers. Whoever had the worst of it, the

fight would be sensational.

When

made prisoner she was on the way to the court of France, in which her

rebellious sons could always find aid. Aquitaine was all but in open

revolt against the Norman interloper it was only through her that

Henry had held that province at all. Scotland was ready for trouble

at any time; Ireland was in tumult; the Welsh were in a permanent

state of revolt. But Norman though he was, the King had won his way

among his English subjects. They never forgot that he was only half

Norman after all. His Saxon blood, cold and stubborn, steadied his

Norman daring, and he could be alternately bold and crafty.

Eleanor

of Aquitaine was more an exile in her husband's own country than she

would have been in France or Italy. His people might rebel against

their King themselves, but they did not sympathize with her for doing

it. They were as unfeeling as their gray, calm skies.

Instead

of weeping and bemoaning herself she made life difficult for her

household. Oddly enough the two English girls got on with her better

than the rest. Mary's even, sunny temper was never ruffled, and

Barbara's North-country disposition had an iron common-sense at the

core. The gentle-born damsels of the court were too yielding.

When

little hot flashes lightened among the far-off hills, and a distant

rumble sounded occasionally, the Queen was pacing to and fro on the

top of the great keep. It was not the safest place to be in case of a

storm, for the castle was the highest building in the neighborhood.

Philippa, working sedately at a tapestry emblem of a tower in flames,

looked up the stairway and shivered as if she were cold.

"Mary,"

she queried, as the still-room maid came through the bower, "where

is Master Tomaso?"

"In

his study, I think," Mary answered. "Shall I call him?"

"Nay

— I thought — " Philippa left the sentence unfinished and

folded her work; then she climbed the narrow stair. When the Queen

turned and saw her she was standing with her slim hands resting on

the battlement.

"What

are you doing away from your tapestry-frame, wench?" demanded

her mistress. "Are you spying on me again?"

''Your

Grace," Philippa answered gently, "I could never spy on you

— not even if my own father wished it. I — I — was talking with

Master Tomaso last night, and he said strange things about the stars.

I would you could have heard him."

The

Queen laughed scornfully. "As if it were not enough to be

prisoned in four walls, the girl wants to believe herself the puppet

of the heavens! Look you, silly pigeon, if there be a Plantagenet

star you may well fear it, for brother hates brother and all hate

their father — and belike will hate their children. Were you asking

him the day of my death?"

"I

was but asking what flowers belonged to the figures of the zodiac in

my tapestry," answered Philippa. "He says that a man may

rule the stars."

"I

wish that a woman could," mocked the Queen. "How you silly

creatures can go on, sticking the needle in and out, in and out, day

after day, I cannot see. One would think that you were weavers of

Fate. I had rather cast myself over the battlements than look forward

to thirty years of stitchery!" She swept her trailing robes

about her and vanished down the stairs. Philippa, following, saw with

a certain relief that she turned toward the rooms occupied by old

Tomaso. The physician was equal to most situations. Yet in the

Queen's present mood anything might arouse her anger.

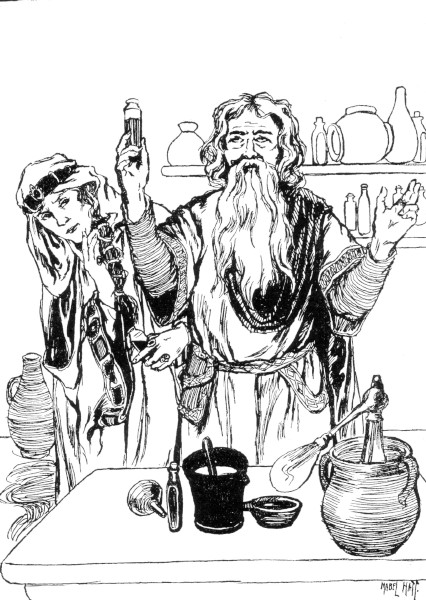

The

study was of a quaint, bare simplicity in furnishing. It had a chair,

a stool, a bench under the window, a table piled with leather-bound

books, a large chest and a small one, an old worm-eaten oaken dresser

with some flasks and dishes. A door led into the laboratory, and

another into the cell where the philosopher slept. As the Queen

entered he rose and with grave courtesy offered her his chair, which

she did not take. She stood looking out across the quiet hills, and

pressed one hand and then the other against her cheeks — then she

turned, a dark figure against the stormy sky.

"They

say that you know all medicine," she flung out at him. "Have

you any physic for a wasted soul?" With a fierce gesture she

pointed at the half-open door. "Why do you stay in this dull

sodden England — you who are free?"

"There

are times, your Grace," the physician replied tranquilly, "when

I forget whether this is England or Venetia."

The

Queen moved restlessly about the room, and stopped to look at an

herbal. "Will you teach me the properties of plants?" she

asked, as she turned the pages carelessly. " With Mary's help we

might make here an herb-garden. It is well to know the noxious plants

from the wholesome, lest — unintentionally — one should put the

wrong flavor in a draught."

Tomaso

had seen persons in this frame of mind before. He had taught many

pupils the properties of plants, but he had his own ways of doing it.

In his native city of Padua and elsewhere, there were chemists who

owed their fame to the number of poisons they understood.

"I

have some experiments in hand which may interest your Grace," he

answered. "If you will come into my poor studio you shall see

them." He led the way into the inner chamber where no one was

ever allowed to come. The walls were lined with shelves on which

stood jars, flasks, mortars and other utensils whose use the Queen

could not guess. Tomaso did not warn her not to touch any flask. She

handled, sniffed and all but tasted. She finally went so far as to

pour a small quantity of an unsensational-looking fluid into a glass,

and a drop fell on the edge of her mantle, in which it burned a clean

hole.

"Tomaso

seemed not to have seen her action"

Tomaso

was pouring something into a bowl from a retort, and seemed not to

have seen the action. Then he added a pinch of a colorless powder,

and dipped a skein of silk into the bowl. It came out ruby-red.

Another pinch of powder, another bath, and it was like a handful of

iris petals. Other experiments gave emerald like rain-wet leaves in

sunlight, gold like the pale outer petals of asphodels, ripe glowing

orange, blue like the Mediterranean. Then suddenly the light in the

stone-arched window was darkened and thunder crashed overhead. The

little brazier in the far corner glowed like a red eye, and Tomaso

had to light a horn lantern before the Queen could see her way out of

the room.

"We

shall have to wait, now, until after the storm," he said, as he

led the way into the outer room. "I am making these experiments

for the benefit of a company of weavers whom a young friend of mine

has brought here. The young man — he is a wool-merchant — has an

idea that we can weave tapestry here as well as they can in Damascus

if we have the wherewithal, and I said that I would attend to the

dyeing of the yarn."

The

Queen gave a contemptuous little laugh and sank into the great chair.

"These Saxons! I think they are born with paws instead of hands!

They are good for nothing but to herd cattle and plow and reap. Do

your stars tell you foolish tales like that, Master Tomaso'?"

"I

did not ask them," said the old man tranquilly. "I use my

eyes when I can. The weavers are Flemish, and I see no cause why they

should not weave as good cloth here as they did at home. They had

English wool there, and they will have it here. There is a Spaniard

among them, and I do not know what he will do when the chilly rains

come, poor imp. He does not like anything in England, as it is."

"Poor

imp!" the Queen repeated. "How do these weavers come here,

so far from any town?"

"Well,

they came like most folk, because they had to come," smiled the

Paduan. "The English weavers are inclined to be jealous folk,

and they took the view that these Flemings were foreigners and had no

right within London Wall — or outside it either, for they were in

a lane somewhere about Mile End. Jealousy fed also on their success

in their work — it was far superior to anything London looms can

do. And certain dealers in fine cloth saw their profits threatened,

and so did the Florentine importers. What with one thing and another

Cornelys Bat and his people had to leave the city, or lose all that

they possessed. The reasons were as mixed as the threads of a

tapestry, but that is the way with life."

"And

why are you wasting time on them?" the Queen demanded.

"My

motives are also mixed," answered the old man. "Being

myself an alien in a strange land, I had sympathy for them —

especially Cimarron, the imp. Also it is interesting to work in a new

field, and I have never done much with dyestuffs. I sometimes feel

like a child gathering bright pebbles on the shore; each one seems

brighter than the last. But really, I think I work because I dislike

to spend my time in things which will not live after me. It seemed to

me that if these Flemish weavers come here in colonies, teaching

their art to such English as can learn, it will bring this land

independence and wealth in years to come. There is plenty of

pasturage for sheep, and wool needs much labor to make it fit for

human use. Edrupt, the merchant — his wife is one of your women, by

the way — says that this one craft of weaving will make cities

stronger than anything else. And that will disturb some people."

The

Queen's eyes flashed with wicked amusement. She had heard the King

rail to his barons upon the impudence of London. She knew that those

who invaded London privilege came poorly out of it.

"Barbara's

husband," she said thoughtfully. "I did not know that he

was a merchant — I thought he was one of these clod-hopping

farmers."

Tomaso

did not enlighten her. Curiosity is the mother of knowledge. He

peered out at his fast-filling cisterns. "This rain-water,"

he observed, "will be excellent for my dyestuffs."

The

Queen gave a little light laugh. "The heavens roar anathema

maranatha," she cried, "and the philosopher says, 'I will

fill my tubs.' You seem to be assured that the powers above are

devoted to your service."

"It

is as well," smiled the physician, "to have them to your

aid if possible. Some men have a — positive genius — for being on

the wrong side. The growth of a people is like the growth of a vine.

It will not twine contrary to nature."

"But

these are not your people," the Queen persisted. "No one

will know who did the work you are doing."

"Cornelys

Bat the tapissier told me," Tomaso answered, "that no one

knows now who it was who set the foot at work by tipping the loom

over, and separated the warp threads by two treadles. Yet that

changed the whole rule of weaving."

"I

have a mind to see this tapestry," announced Eleanor abruptly.

"Tell your Cat, or Rat, or Bat, whatever his name is, to bring

his looms here. If he works well we will have something for our walls

besides this everlasting embroidery. I have watched Philippa working

the histories of the saints this six months, — I believe she has

all the eleven thousand virgins of Saint Ursula to march along the

wall. I am ready to burn a candle to Saint Attila."

Tomaso's

eyes twinkled. That friendly twinkle went far to unlock the Queen's

confidence. "Here am I," she went on impetuously, "mewed

up here like a clipped goose that hears the cry of the flock. If

there is another Crusade I would joyfully set forth as a man-at-arms,

but belike I shall never even hear of it. I warrant you Richard will

lead a host to Jerusalem some day — and I shall not be there to

see."

The

Paduan lifted one long ringer. "You fret because you are strong

and see far. Your descendants may rule Europe. The Plantagenets are a

building race. You can lay foundations for kings of the years to

come. You have here the chance of knowing this people, whom none of

your race did ever know truly. Your tiring women, the men who till

these fields and live by their toil, the churchmen, the traders —

knowing them you know the kingdom. Bend your wit and will to rule the

stars, madam. Thus you bring wisdom out of ill-hap, and in that way

only can a King be secure."

The

Queen sat silent, chin in hand, her eyes searching the shadows of the

room, for the storm had passed and twilight was falling. "Gramercy

for your sermon, Master Tomaso," she said at last, as she rose

to leave the room. "Some day Henry will see that it was not I

who taught the Plantagenets to quarrel. Send for your tapissiers

to-morrow, and I will study weaving for a day."

To

the comfort of all, the Queen was in a gay humor that evening. The

carved ivory chessmen were brought out, and as she watched Ranulph

and Philippa in the mimic war-game Eleanor pondered over the recent

betrothal of Princess Joan to the King of Sicily. "Women,"

she muttered, "are only pawns on a man's chessboard."

"Aye,"

laughed Ranulph, as his white knight retreated, "but your Grace

may remember that the pawn when it comes to Queen may win the game."

The

bulky loom of Cornelys Bat was set up next morning in the old hall,

and the Queen came down to watch the strange, complex, curious task.

Then she would take the shuttle herself and try it, and to the

surprise of every one, kept at the task until she might well have

challenged a journeyman. While the threads interlaced and shifted in

a rainbow maze her mind was traveling strange pathways. The shuttle,

flung to and fro in deft strong skill, was not like the needle with

its maddening stitch after stitch, and there was no petty chatter in

the room. The Flemish weaver might be silent, but he was not stupid,

and the drawboy, the dusky youth with the coarse black hair, was like

a wild panther-cub. Such a blend as these weaving-folk, brought

together by one aim, could teach the arbitrary barons their place.

Normandy, Aquitaine, Anjou, Brittany, — England, Scotland, Ireland,

Wales — what a web of Empire they would make! And if into the dull

russet and gray of this England there came a vivid young life like

her Richard's — yellow hair, sea-blue eyes, gay daring, impulsive

gallantry and under all the stern fiber of the Norman what kind of a

tapestry would that be? Thus, as women have done through the

centuries, Eleanor of Aquitaine let her mind play about her fingers.

After

a while she left the work to the weavers and watched Mary Lavender

making dyestuffs under Tomaso's direction. It was fascinating to try

for a color and make it come to a shade. It was yet more so to make

new combinations and see what happened. Red and green dulled each

other. A touch of orange made scarlet more brilliant. Lavender might

be deepened to royal violet or paled to the purple-gray of ashes. The

yarns, as the skillful Flemings handled them, were better than any

gold thread, and the gorgeous blossom-hues of the wools were like an

Eastern carpet.

Presently

the Queen began devising a set of hangings for a State bedchamber,

the pictures to be scenes from the life of Charlemagne the suggested

comparison of this monarch with the Fling had its point. An Irish

monk-bred lad with a knack at catching likenesses came by, and made

the designs, under Queen Eleanor's direction; and during this

undertaking she learned much concerning the state of Ireland. That

ended and the weaving begun, she took to questioning Cimarron the

drawboy.

"I

suppose," she jibed, "men grow like that they live by, or

you would never have been driven out of London like sheep. I may

become lamblike myself some day."

Cimarron's

white teeth gleamed. "I would not say that we went like sheep,"

he retorted, and he told the story of their going. "There were

the old folk and the little ones, your Grace," he ended. "The

master cares for his own people, and his work. He does not heed other

folk's opinions."

The

Queen laughed gleefully. "I wish I had been at that hunting —

the wolves driven by their quarry. My faith, a weaver's beam is not

such a bad weapon after all."

More

than ten years after, when Richard I. was crowned King of England,

one of his first acts was to make his mother regent in his absence.

It was she who raised the money to outbid Philip of France when Coeur

de Lion was to be ransomed. As one historian has said, she displayed

qualities then and later, which prove that she spent her days in

something besides needlework. She did not stay long at King's Barton,

but one of Cornelys Bat's tapestries was always known as the Queen's

Maze. In one way and another during the sixteen years of her

captivity she learned nearly all that there was to know of the temper

of the people and the nature of the land.

|