|

|

Click Here to return to |

|

|

Click Here to return to |

Our Little Indian Cousin

THEY call him Yellow Thunder. Do not be afraid of your little cousin because he bears such a terrible name. It is not his fault, I assure you. His grandmother had a dream the night he was born. She believed the Great Spirit, as the Indians call our Heavenly Father, sent this to her. In the dream she saw the heavens in a great storm. Lightning flashed and she constantly heard the roar of thunder. When she awoke in the morning she said, “My first grandson must be called ‘Yellow Thunder.” And Yellow Thunder became his name.

But his loving mamma does not generally call him this. When he is a good boy and she is pleased with him, she says, “My bird.” If he is naughty, for once in a great while this happens, she calls him “bad boy.”

For some reason I don’t understand myself, she rarely speaks his real name. Perhaps it is sacred to her, since she believes it was directed by the Great Spirit.

Yellow Thunder lives in the forests of your own land, North America. His skin is a dull, smoky red, his eyes are black and very bright, his hair is black and coarse. His body is straight and well formed. He can run through the woods as quickly and softly as a deer. He lives in a bark house made by his mother. His father is strong and well, yet he did not help in building it. He thinks such work is not for men. It is fit only for women.

When I tell you how it is made, you will not think it is very hard work. Yellow Thunder’s patient mamma chose the place for her home, and then gathered some long poles in the forest. She set these poles in a circle in the ground, bent them over at the top, and tied them. She left a small hole at the top. The framework of the house was now complete. What should she have for a covering? She went out once more into the woods and got some long sheets of white birch bark. At the end of each sheet she fastened a rim of cedar wood. The sheets of bark were hung on the framework, with the rim at the bottom of each one, and the house was finished. The rim would be useful in keeping the bark from being lifted by the winds. But, if there should be a severe storm, the Indian woman would lay stones on the rims to keep the bark down more firmly still.

This is Yellow Thunder’s simple home, summer and winter. You would probably freeze there in the cold days of December, but the Indian boy was brought up to endure a great deal of cold.

Let us look inside. We must first lift the deerskin which hangs in the doorway. Does the family sit on the cold, bare ground, do you think? Oh, no; Yellow Thunder has helped his mamma make good thick rugs out of the bullrushes and flags which they gather every autumn. These rugs are very pretty, for they are woven and dyed with the bright colours the Indian women know how to make. There are many of these mats, because they are used for many purposes. Yellow Thunder sleeps on one of them at night. In the daytime he sits on a mat whenever he is in the house. But he is such a strong lad, he is out-of-doors nearly all the time, both in sunshine and in storm.

In the middle of the house you will notice there is a bare spot covered with clean sand. This is the place where the fire is made. It is carefully swept when there is no fire. If you look directly over the fireplace, you can see the sky. On rainy days, unless the mother is cooking, she keeps the hole covered with a piece of deerskin, that the inside of the house may be dry.

But how does she prepare the food for breakfast, for that is the principal meal of the day to the Indian? A strong hook is fastened in the framework of the house, above the fireplace. The Indian mother hangs a pot on the hook, puts in the meat or fish, and it boils quickly over the burning twigs which her little boy has gathered.

Let us look around the wigwam. Of course, you have long ago heard that name for the Indian’s house. What beautiful baskets of rushes those are! I wonder how the red men discovered the way of making such beautiful colours. Besides many other things, the jewelry and clothing of the whole family are kept in these baskets. Look up at the sides of the hut and notice the bows and arrows. And, yes! there is a real tomahawk, with its sharp edge sticking in that corner. Ears of corn braided together are hanging from the framework.

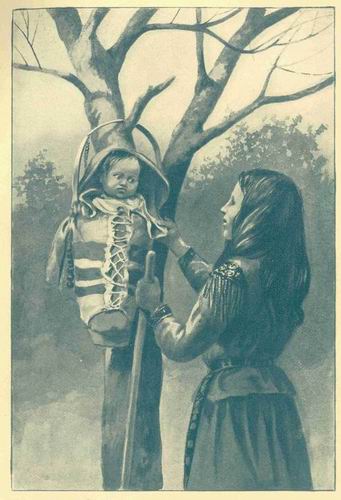

But the prettiest thing we see is the baby’s cradle, fastened to a peg. Two bright black eyes are looking out of it, and that is all we can see of Yellow Thunder’s baby sister, “Woman of the Mountain.” It took the loving mother a long time to make that cradle. She was very happy while doing it, for she loves her baby tenderly.

It is hardly right to call it a cradle. Baby-frame is a better name. It was made in three pieces, out of the wood of the maple-tree, — a straight board about two feet long for the bottom, a carved foot-board, and a bow which is fastened to the sides and arches over the baby’s head. These are all bound together with the sinews of a deer. It is lined with moss, and then Woman of the Mountain is fastened in her queer little bed with straps, which her mamma has made beautiful with bead work. Moss is placed between her feet, her hands are bound at her side, her feet are bound down also, and a beaded coverlet is placed over her tiny body. She looks like a little mummy.

If it is stormy she is hung up on a peg in the hut to swing, but if it is a pleasant day, she swings on the branch of a tree and watches the leaves flutter and the birds sing. She is a happy little baby, although you would hardly think it possible. She got used to her imprisonment almost as soon as she was born. She doubtless thinks it is all right.

When mamma goes out into the forest to gather wood, or into the corn field to work, Woman of the Mountain goes too. The baby-frame is fastened on her mother’s back by a pretty beaded strap bound over the woman’s forehead.

When the Indian baby was only two days old, she was fastened into her cradle and carried all day on mamma’s back while she was weeding the garden. To be sure, the woman stopped two or three times to feed her baby, but the little thing was not once taken out of her frame.

Perhaps you would like to hear a lullaby the Indian mamma often sings to her little one as she swings in her frame. I fear you could not understand the Indian words, so I will give them as Mrs. Elizabeth Oakes Smith wrote them in English:

|

“Swinging, swinging,

lul la by,

‘Tis your mother

loves you, dearest,

“Swinging, swinging,

lul la by, |

You can understand from this how dearly the Indian mother loves her baby,—just as dearly, I do not doubt, as your own mamma has always loved and cared for you.

But what is Yellow Thunder’s stern-looking father doing all the time? He has no store to keep, no mill to grind, no factory to work in. There are only three things which deserve his attention. At least that is what he thinks. He hunts or fishes, goes to war, and holds councils with the men of his tribe. Everything else he believes is woman’s work, and from the Indian’s standpoint, woman is much beneath a man.

After all, the men’s work is really the hardest. Sometimes it is easy for them to find plenty of food. Then Yellow Thunder’s father comes home rejoicing with the big load he carries. Perhaps he has a red deer hanging over his shoulder; perhaps it is a bear which he has chased many miles before he could get near enough to kill it; or it may be some raccoons for a delicious stew.

But, again, it may be stormy weather. The rivers are frozen over and snow covers the ground. Then, perhaps, the hunter has little success with his bow and arrow, and searches long and far before he can find anything to satisfy his children’s hunger. He feels sad, but not for a moment does he think of complaining or giving up. It is his duty to obtain food for his family. It does not matter how cold he gets or how wet he may be. He keeps travelling onward. He will not give up. If he does not at last get enough for all, he will insist on his wife and children satisfying their hunger first. He would scorn to show that he himself is tired, or hungry, or suffering in any way.

We can understand now why the Indian baby is pinned down in its cradle and not allowed to move freely. It is its first lesson in endurance. It must learn to be uncomfortable and not to show that it is so. It must learn to bear pain, and neither cry nor pucker its mouth. It must learn to appear calm, no matter how it feels.

The hunt is pleasant sometimes, you see, but at others it is work of the hardest kind.

The second duty of the red boy’s father is war. He must protect his home from human and wild beast enemies. But I’m really afraid that it is a pleasure for him to fight. If Indians had not been at war so much among themselves, it would have been far harder for the white people to conquer them. I suppose you children have all heard the story of the bundle of sticks, but I will repeat it.

A certain man was about to die. He gathered his sons around him to give them good advice. He showed them some sticks fastened tightly together. Then he asked each one to try to break the bundle. No one could do it. When he saw that they failed, he separated the sticks, and showed them how easy it was to break each one by itself.

“Take a lesson from this,” said the man. “If you are united and work together, you will succeed in anything you undertake, for no one can break your strength. If, however, you quarrel among yourselves and try to work each for himself, you will be like the separate twigs, — easily broken.”

It has been like this with the Indians. They have fought against each other, tribe with tribe. They are very brave and have great courage. But they have not understood that they should work together. So the white man came and was able to conquer them.

Besides hunting and going to war, Yellow Thunder’s papa is often busy in the council. All matters of business are settled here. New chiefs are chosen at the council; wrong-doers are punished according to what it decides, and treaties with other tribes or the white men are talked over and agreed upon. Sometimes a council will last many days. It is always opened with a prayer to the Great Spirit, thanking him for his good gifts to the people. Each evening, after the business of the council is over, games are played by old and young. It is a time for feasting and pleasure. No business with other people is really settled by a council without gifts of wampum to bind the bargain. Of course you have heard about wampum. Perhaps you have been told it is the Indian’s money. There are two kinds of wampum. One is purple and the other white. The white wampum is shaped into beads out of the inside of large conch shells, while the purple is made from the inside of the mussel shell. These beads are strung on deer’s sinews and woven into belts. A belt of white wampum is a seal of friendship between two tribes. It is the same as a sacred promise which must not be broken. It is the most precious of all things an Indian owns.

Yellow Thunder’s papa is very fond of tobacco. He always carries a beaded pouch filled with it. He believes that the Great Spirit gave tobacco to the Indian. When he smokes it, it opens a way through which he may draw near God, and be taught by him. His pipe and tobacco will be buried with him when he dies, as he thinks they will be needed on his journey toward heaven. He smokes at the council. He smokes around the camp-fire when he is away hunting. He smokes in the evening time as he sits with his friends and tells stories of the chase or listens to legends of his people.

I hardly know what this Indian father would do without his pipe, as it seems to give him so much comfort and pleasure.

See! here he comes now. Yellow Thunder is at the door of the lodge, watching him as he walks quickly down the forest path. He is truly called a “brave.” He looks as though he would fear no danger. How straight is his body, and how strong are his muscles!

He wears leggings of deerskin, finely worked with beads. They are fastened just above his knees. A short kilt is gathered around his waist. It is also made of deerskin, but is worked around the edge with porcupine quills stained in several colours. It is bitterly cold to-day, so he wears a blanket over his shoulders. His head is shaved bare, excepting the scalp-lock at the back. It must be this which makes him look so fierce.

I want you to notice his feet. They step softly and yet firmly. You could not walk as he does. Perhaps you have pointed shoes with high heels. The Indian would look with scorn upon these. What! Cramp the toes with such uncomfortable things! Impossible! He covers his feet in the most sensible manner with the soft moccasins made by his wife. They fit his feet exactly. He can run like a deer, or creep along the ground like a wildcat in these coverings, and no one will hear him coming. Each moccasin is made of a single piece of deerskin, seamed at the heel and in front. The bottom is smooth and without a seam, while the upper part is worked with beads.

Yellow Thunder’s good mamma uses a curious needle and thread. The needle is made from the bone of a deer’s ankle, and her thread is of the sinews of the same animal. What would the Indian have done without the deer in the old days before the white man came to this country? I can’t imagine, can you?

This animal furnished much of his food and clothing; ornaments were made of his hoofs; needles and many other things came from his bones. Even the brains of the creature were used in tanning skins of animals. They were mixed with moss, made into cakes, and dried in the sun. This mixture will keep a great length of time. Whenever it is needed, a piece of this brain-cake is boiled in water, and the skin is soaked in it after the hair is scraped off. Then it is wrung out and stretched until it is dry. But even then the skin is not ready for use. It will tear very easily. It must be thoroughly smoked on both sides. This work all belongs to Yellow Thunder’s mamma. His father has nothing to do with it.

Suppose we follow the red man into his home. Ugh! What a smoke there is inside! We can hardly see across the wigwam. We shall need to lie down on the mat as the Indian does. Our eyes will be blinded unless we do this. The wife has a good meal waiting for her husband, but she will not eat till he has finished. That is Indian good manners.

His wooden bowl and plate, together with a boiled corn-cake, are placed on the mat in front of the man. Venison stew is served him out of the big pot, and a dish of sassafras tea is also set before him. There is no milk to put into this queer drink, but if he wishes to sweeten it, he can add some delicious maple syrup. This is certainly not a bad meal for any one.

The red man eats and drinks, while scarcely a word is said to his waiting family. When he has finished his meal, he will light his pipe for a quiet smoke, after which his wife and child satisfy their hunger.

Yellow Thunder’s mamma knows how to prepare many a good dish. She can make several different kinds of corn bread. She prepares soups of deer and bear meat. She boils the hominy, on which our little red cousin pours the maple syrup. She makes teas of wild spices and herbs which grow near the hut. But these drinks are not likely to keep Yellow Thunder awake at night. Neither is there danger of his starving, so long as his father can hunt and his mother can gather her crops. His food is suited to make him strong and healthy, and he does not miss the dainties of which you are so fond.

The stern-looking father never thinks of interfering in the management of the home. That is his wife’s right. She gives him his sleeping-place and the corner in which he shall put his belongings. She decides on what shall be cooked, and what shall be stored away. She is the ruler in the home.

But, on the other hand, he does not expect her to scold. She should always be obliging and happy in entertaining his friends. She should be ready to furnish him a good meal whenever he comes home.

As yet, he does not take much notice of his only son. He does not correct the boy’s faults. He seldom takes him on his hunts. He has left all care of the boy to his wife up to this time.

But Yellow Thunder is now twelve years old. He will soon be a man. In a year or two, at most, his father will begin to make a companion of his son in hunting and fishing. He will teach him the ways of a brave Indian warrior. Then there will be no more woman’s work for Yellow Thunder.

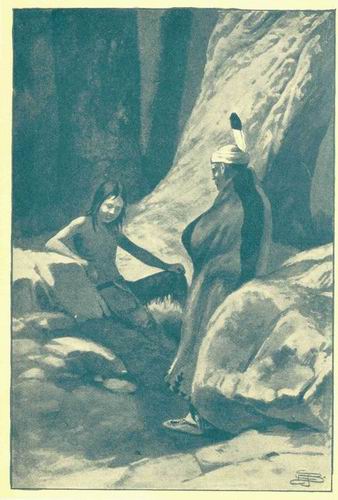

When the time comes for this great change in his life, he will go out into the forest to fast. No one will insist on his doing this. He will himself desire it. It is the same as a baptism to a young Indian. His father will go with him to the lonely spot where he decides to stay. He will give his son wise words of counsel. He will urge him to be brave and keep his fast as long as possible. He will be able to show by this how much courage and spirit he possesses, and how great a man he desires to be. Then he will leave his son alone and go back to the village.

A day passes by, and Yellow Thunder grows faint. Two days now are gone, and the boy’s thirst is intense. At the end of three days his father comes back and finds his son lying weak and dizzy beneath the trees. He gives him a little water, but no food, for Yellow Thunder says he can fast still longer.

The father goes away again, leaving the son to watch for the visions which will surely come. It will be decided now what the red boy’s future will be. The longer he can fast, the greater man he will become among his people. No one can be a chief unless he has fasted many days at the beginning of his manhood.

We cannot tell what Yellow Thunder will be, but we know that his visions will always be remembered. He believes that his guardian spirits will appear in some form or another to him, and he will get instruction about his future life. He will endure his fast bravely as long as possible.

It sometimes happens that Indian boys die at this time of fasting, but we feel sure that Yellow Thunder will live and be a joy to his parents to the end of their lives.

But how is the Indian mother preparing him for this great test? She teaches him, first of all, to obey. In no other way would it be possible for him to become a great man. He must heed everything that his father and mother tell him. He must always be ready to do their bidding. It is the greatest token of rudeness to appear curious, therefore he must ask no questions. He must love the truth. A lie is almost unknown among the Indians; they scorn it as the mark of a cowardly and mean nature. He must be brotherly to all creatures, and ready to give to others always.

Yellow Thunder has never seen a pauper or beggar in his life. Whenever any one comes to his home, his mother hastens at once to prepare food for the visitor. It is almost a law to her to do so. If relatives should come for a visit, they will be made welcome and allowed to stay as long as they desire. If they should remain for the rest of their lives, they would never be asked to leave. “Be hospitable to all,” is a maxim planted in the heart of every Indian child.

Yellow Thunder is taught that everything should be shared in common. The Indian does not say, “My land.” It is always “Ours.” The people of a tribe are truly brothers to each other.

The red boy’s mamma does not need to teach him that theft is wrong. It is almost unknown among his people. The idea of doing such an unbrotherly thing does not enter their heads. No wonder there are neither poorhouses nor prisons among these people. We call them savages, but there are many things we could copy with profit from them. Don’t you think so, children? “Live and learn,” is an old saying, and I think we would do well to remember it when we read the lives of our cousins in many lands.

Yellow Thunder does not go to church or Sunday school. I doubt if Sunday is any different to him from any other day. But his mamma has taught him that there is one loving Heavenly Father for all. If Yellow Thunder is good and brave, he will go to the “happy hunting-grounds” when he dies. At least, this is what he is taught to believe. There will be enough food and an abundance of animals to kill. Everything that the Indian loves best to do in this life, he thinks can be found in his heaven. But there is no place there for the white man. George Washington was the only white man who ever lived whom they thought fit to enter their paradise. The exception was made in his case because he was brave and good, and treated the Indians fairly and justly.

Yellow Thunder’s mother often tells him of a prophecy which was made long ago by the wise men of her tribe. They said that a great monster, with white eyes, would come out of the East and consume the land. Did the prophecy come true, you ask? Yes, my dears, it was the white race.

When Yellow Thunder thinks of the great forests which his people once owned, and of the numbers of animals roaming there, when he remembers the wars which have been fought and lost with the “great monster,” his heart grows bitter.

Don’t blame him, children, but feel sorry for your little Indian cousin. His people have certainly had a hard time. They have been very cruel in warfare with us, but they felt they were treated unjustly, and we were taking their homes away from them.

Yellow Thunder believes in the Great Father, as I have told you. His mother has also taught him that there are many spirits, both good and bad. God made the good spirits to help him in care of this great world. The Indian believes that the wind is a spirit of great power. The thunder is another spirit, whom he calls Heno. Heno makes the clouds and the rain. It is he who forms the thunderbolt and sends it to destroy the wicked.

The Great Spirit is very kind to give men such a helper, and when the harvest time comes, Yellow Thunder gives him thanks and prays to him that he will continue to send Heno into the world.

There is an old legend among the Indians that Heno once dwelt in a cave behind Niagara Falls. The mighty rushing noise of the water was pleasing to him.

Yellow Thunder pictures the Spirit of the Winds to himself. This spirit has the face of an old man who is always in the midst of discord, for the four winds are never at peace with each other.

Then there are the spirits of Corn, of Beans, and of Squash. Each one of these is looked upon as a friend of the red race, for these vegetables are prized by them above all others.

It is believed that these spirits have the forms of beautiful women, and that they dwell happily together and are very fond of each other.

There are many other good spirits. The red boy feels their presence in the forests and out upon the waters. They are ever around him to protect him when he is good. But, if he should be bad? Ah! There are many evil spirits, too, who are only too ready to work mischief and harm among men, if they have the chance.

Yellow Thunder believes that animals have souls, only they are not as wise as men. Sometimes, when they have done great wrongs, men have been changed into animals. Our cousin thinks the wolf was once a little boy like himself, but the poor little fellow was neglected by his parents, and was transformed into an animal. The raccoon was once a shell on the seashore. What curious ideas these are! Where do you suppose they came from before they lived in the minds of the red race?

While we are speaking of these things, I will stop and tell you of something that happened at Yellow Thunder’s house the other day. His father, Black Cloud, came home, from the hunt bringing a big black bear. It was so heavy that two other men had to help in carrying it. They had discovered the creature in a hollow tree and had easily killed it. But now comes the amusing part of the story. As soon as the bear was laid down in front of the hut, Yellow Thunder and his mamma went up to it and began to kiss and stroke the dead animal’s head. Black Cloud did the same, and then they all begged the bear’s pardon for having killed it. Black Cloud said, “I would not have done so, had we not needed food, so I know you will forgive me.”

Then the head of the bear was cut off and laid on one of the best mats. It was decorated with all the jewelry owned by the family. There were silver armlets and bracelets, as well as belts and necklaces of wampum. Tobacco was placed in front of its head, while each one in turn lighted a pipe and blew the. smoke into the bear’s nostrils. This was to turn away its anger from those who had killed it. Black Cloud then made a speech to the bear.

I suppose these people believed that the spirit of some human being had come to live in the animal’s body, and they looked upon it as a friend whom they were forced to kill.

After all this ceremony, the fat of the bear was boiled down to oil, the meat was cut up and dried for future use, while the head was put into the pot to cook for dinner. I do not doubt that when the bear stew was served, Yellow Thunder did not give a single thought to the idea of eating a friend. He had done his duty in asking its forgiveness, and that was enough.

What kind of a school does Yellow Thunder attend? It is a very large one. It covers the forests, the rivers, and the lakes. And who is his teacher? The very same one who gives so many lessons to Anahei in the hot land of Borneo, so far away. Dame Nature is her name. She is usually loving and kind, but sometimes she shows her anger in the storms and winds which rage about our little cousins.

The lessons which Yellow Thunder learns are very different from those given Anahei, for they live in vastly different climates. Anahei, you remember, is near the equator, while Yellow Thunder lives in the temperate lands. He learns from the ice and the snow, he sees different animals, plants, and trees.

He is quicker, stronger, and brighter than Anahei, for the cold winters make him so. His eyes are very sharp, his ears will hear sounds that yours would not notice, his feet can travel many miles without his having a thought of being tired.

He has no compass, and yet he can journey in the forest in any direction he may choose without losing his way. How does he do it? He has learned to notice that the tops of the pine-trees generally lean toward the rising sun. He has discovered that moss grows toward the roots of the trees on their north side, while the largest branches of trees are usually found on the south side of their trunks.

In fact, Yellow Thunder has learned so many of Nature’s secrets that, if he should reveal them all, they would fill many books.

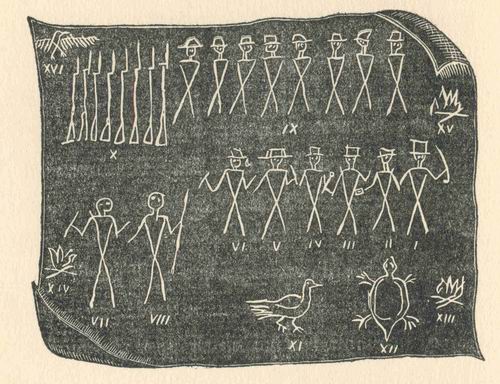

This cousin of yours knows nothing about writing as you understand it. He puts all Ms stories into pictures. He could send you a letter with two or three pictures, telling a long, long story, but I don’t believe you could understand one - quarter of it. His little Indian friends would be able to read it all at a glance.

Their eyes are well trained, although they know nothing about your alphabet or vertical penmanship.

Black Cloud often finds a bark picture hanging to some tree while he is hunting. It is better than any guide-post such as we make, because it will tell him so much. He will know from it that other red men have journeyed this way, and what kind of experience they had. Perhaps it will warn him of danger, or explain to him the best direction to go if he wishes to find more game.

You may like to see such a picture. I will copy one which Mr. Henry Rowe Schoolcraft saw while he was living among the Indians. He was exploring the country with a party of white men and two Indian guides. They lost their way during the day and camped out all night in a deep forest. Before they went away on the next morning, the Indian guides hung this picture on a tree:

They thought it might be of use to others passing there.

Figure I. is the officer who commanded the party. You may know this because he carries a sword. II. has a book in his hand. This shows he is the secretary. III. carries a hammer, because he is a geologist. IV. and V. are attendants. VI. is the man who interprets to the party the words of the Indian guides. The group of eight figures marked IX. consists of soldiers. Their muskets stand in the corner, and are marked X. VII. and VIII. are the two Indian guides. You will notice that they are drawn with no hats; which shows at once that they are not white men. XIII., XIV., and XV. represent fires, showing that each separate group—officers, soldiers, and Indian guides — had a separate one. Figures XI. and XII. are the pictures of a prairie-hen and a tortoise, which were the only game they had been able to kill that day. The pole to which the piece of bark was fastened leaned in the direction which the party was going to travel. There were three notches in the pole to show the distance they had already journeyed.

Yellow Thunder learns to read these bark pictures, and also to make them himself. He enjoys this work very much, and can tell a long story quickly. If I were you, I would write him a letter and ask him to answer it in his own way.

This cousin of yours has many things to keep him busy. I have already told you of the mats and baskets which he helps his mother in making. He goes with her to get the bark which she will use in mending the wigwam and making many useful things.

He makes barrels out of red elm bark in which to store groundnuts, corn, and beans. He cuts ladles out of wood, which the family will use in eating their soup and hominy. On the end of each ladle Yellow Thunder carves the figure of some animal. Perhaps it is a beaver or a squirrel. He does it very neatly. Whatever the Indian boy does, he does well.

Yellow Thunder makes sieve-baskets out of splint. His mother can sift the corn-meal through one of these as nicely as your mamma can do it with her wire sieve.

He makes salt-bottles out of corn-husks, wooden bowls and pitchers, and many other things for the simple housekeeping. All this work is done during the cold winter months, while his mother is making moccasins and kilts for his father and himself.

When spring opens, she must till the ground for her corn, and Yellow Thunder can now be of great help. She will miss him greatly when he begins to hunt with his father. She will then have all this work to do alone.

I wish you could see the Indian woman’s garden. It is kept so carefully, I don’t believe you would be able to find a weed. Yellow Thunder’s mother did a queer thing the first night after it was planted. She stole out of the wigwam alone into the darkness. She went behind a bush, and took off all her clothing. Taking her skirt in her hand, she ran swiftly around the field of corn, dragging the garment after her. She believed this would keep away all insects which might destroy the crop, and that now it would be sure to yield well. For what a sad thing it would be if winter should come with no bread to eat through the long months!

Yellow Thunder is very fond of his mother’s corn bread. The corn is first hulled by boiling in ashes and water. The tough skin will now slip off easily. After being washed and dried, it is pounded in a mortar into flour. Then it is sifted and made into cakes about an inch thick. These cakes are dropped into boiling water, and are quickly made ready for our red cousin to eat. Since he was a baby, he has lived almost entirely on corn bread, together with the game and fish which his father brings home.

Yellow Thunder eats something on his corn cakes which you like as much as he does himself. It is maple syrup. The sugar which his mother makes from it is the only kind he has ever tasted in his life. It is his work to tap the trees in the spring, and bring home the jars of sap, which his mother will boil down to syrup and sugar.

When her husband goes out on a long hunt, he must take food with him, as it may be a long time before he gets any game. He cannot carry the boiled corn cakes, as they would soon crumble and grow sour. His good wife roasts some corn until it is quite dry. She pounds it into powder and mixes it with maple sugar. It is packed away in Black Cloud’s bearskin pocket. He need not worry about hunger now, even if he is away from home many days. He has everything he needs to keep hunger away.

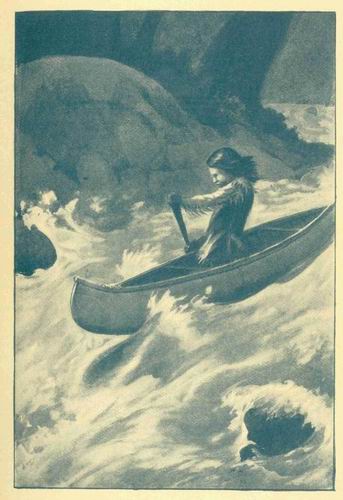

Yellow Thunder is very proud of the beautiful canoe he has just finished. He had to search a long time before he was able to find a tree which suited him. He wanted to make his canoe of birch bark because it is much lighter than the bark of the elm-tree, of which his father’s boat is made.

He needed a strip at least twelve feet long, because the canoe must be made of one piece. Two of his boy friends went with him and they at last obtained a strip which was just right. They helped him bend it into shape, until the side pieces came together in two pointed ends. How do you suppose they fastened the edges together? They made thread out of the bark itself, and with this Yellow Thunder sewed the pieces together.

He next got strips of white ash for the rim of his canoe, because the wood of that tree is very elastic. The boat must be made stronger still with ribs of the ash, and the work is done.

The canoe is a little beauty. It is so light that the red boy can lift it out of the water and carry it with the greatest ease from place to place. I wish you could see him as he shoots down the river in his boat. He moves so rapidly, he will be out of sight in a few minutes.

The Indians of the northwestern part of our country used to make their canoes of cedar logs. The cedar trees there grow so large that canoes eighty feet long, and large enough to hold one hundred men, were made of a single piece. One was exhibited at the Columbian Exposition at Chicago. It was twelve feet wide.

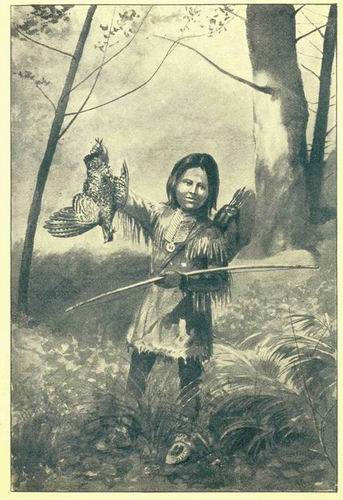

Yellow Thunder has taken his bow and arrows with him to-day, as he may come upon a flock of wild ducks. He would like to surprise his mother with some birds for supper.

He can shoot well. He will not fail to secure some game. He has practised archery ever since he was a tiny little fellow. He would feel himself disgraced for ever if he should disappoint his father when they go out to hunt.

I can’t tell you how many bows and arrows he has already made in his lifetime. He has now grown so large and strong that he uses a bow three and a half feet long. It has such a difficult spring that I fear you could not bend it far, but Yellow Thunder can set his arrow to the head with ease. But it takes skill and great strength to do it.

Perhaps you wonder why the arrow is feathered at the end. This will make it go straight ahead in the direction in which it is sent. Sometimes Yellow Thunder uses arrowheads cut out of flint. They are dangerous things, and will kill deer and even men. Indians have often been known to place poison on the arrow-heads they used in warfare. The agonies of the men who were shot by them were terrible indeed.

Black Cloud has not been to war since Yellow Thunder was born. There are so few of the red race now, and the numbers of the white men are so great, that there is not much chance of warfare.

However, many stories are told in Black Cloud’s lodge of the good old days when the war-whoop was commonly heard and the tomahawk and scalping-knife were in constant use. Yellow Thunder often passes by the grave of a great Indian chief, and thinks about that hero’s bravery in battle. This grave is reverently marked and carefully fenced in. The boy wishes he had a chance to leave such a memory.

At the head of the grave there is a stick with the figure of a wolf carved upon it. It is the symbol, or “totem” of the chief’s tribe. Below the wolf there are many strokes of red paint, which Yellow Thunder likes to count, for each stroke tells of a scalp taken in warfare.

Not many miles up the river above Yellow Thunder’s home, beavers are hunted. Black Cloud likes to catch them, because their flesh is good to eat, and the skin is covered with fine fur. Last winter he allowed his son to go with himself and a party of men to hunt for this clever little creature.

Yellow Thunder believes that the beavers were once people and able to speak like himself. But they were too wise, so the Great Spirit took away this power and changed them into these animals.

I wonder if you have ever seen a beaver’s house. He usually makes it of the young wood of birch or pine trees, and builds it a short way out in the river, so that it is surrounded by water. He shows a great deal of skill in making his home. It has a roof shaped like a dome. It reaches three or four feet above the surface of the water.

There are generally only two young beavers in the family. The first year they live with their parents. The second year they have a room built next to the main house for their special use. By this time they are old enough to help their father and mother get food. They eat great quantities of roots and wood, but they like the wood of the birch and poplar trees best of all.

When the young beavers are two years old, they leave their old home, and choose a new place in which to build houses for themselves. Once in a great while, hunters find beavers that the Indians call “old bachelors.” This is because they live alone, build no houses, but make their homes in holes they find, or dig out for themselves.

The beaver always makes holes in the banks of the river near his house. The entrance to such a hole is below the surface of the water, so that if the beaver is attacked in his house, he can flee for safety to his hiding-place in the bank.

Now let us return to Yellow Thunder and his beaver hunt. It was a bitter cold day and the river was frozen over in some places, but that would be so much the better if the hunters hoped to secure their game. They journeyed by the riverside for several miles. There was a heavy fall of snow, but they moved along quickly with the help of their snowshoes, till one of the men whispered: “I see it. Stop!”

Sure enough! A few feet away from them and from the bank rose the roof of a dam above the ice. One of the men tried the ice and found it was thick enough to bear them.

Yellow Thunder was told to remain where he was on the bank, while the rest of the party took heavy tools in their hands and went over to the beavers’ house. They quickly destroyed it. But the beavers? What had become of them? They did not stay in their house to have it broken down over their heads. They were too wise. When the first alarm was given, they hurried through the water, under the icy covering of the river, to a hiding-place in the bank. They had made it long ago to be ready in case of danger.

Would the Indians succeed in finding them? Remember that nothing could be seen to show where the beavers had gone. The hunters crept along the ice on the edges of the river, and kept striking it with their mallets. If they should hear a hollow sound as they struck the ice, they would know they had discovered the beavers’ hiding-place.

Ah! sure enough! It is Yellow Thunder himself who says: “Quick, father, come here; I have found it I know this is a hole because of the noise the water makes underneath. Beavers are breathing there, or it would not move so quickly.”

Black Cloud hurries to the spot and the ice is cracked in an instant. Yes, his son is right. A family of beavers is inside the hole. They must be taken quickly, or they will escape. There is but one way to do it. The hunter must reach his hands into the hole and pull the animals out. Their teeth are very sharp, and they will do their best to bite him, but Black Cloud does not think of that. He is quickly at work and pulls out one after another.

There are four beavers in all, — two old ones and their young about two years of age. They are soon killed and ready to be skinned. How beautiful and glossy the fur is! It is at its very best in midwinter.

This has been a fine day’s sport, and Black Cloud has received only one bad bite in his wrist. It must cause him a good deal of pain, yet he does not show that he feels any. He binds up his wrist, and nothing is said about it.

When they reach home Yellow Thunder’s mamma will take the tails of the beavers and put them in the pot to boil. The Indians think they are a great delicacy. They will make a feast, to which Black Cloud has gone to invite his friends.

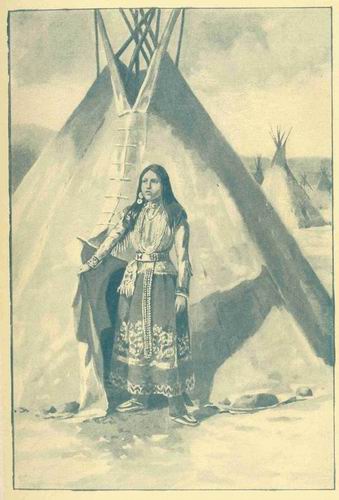

His wife is standing in the door of the wigwam, waiting for the return of her husband and son. She has dressed herself with great care to-day, and has a really beautiful costume. Just imagine your mamma in a dress like hers. She wears long leggings of red cloth reaching from above her knees down over her moccasins. They are worked with beads around the edges.

A long time ago the Indian women made their clothing of deerskins and embroidered them with porcupine quills, but nowadays they buy cloth and beads of the white traders in exchange for furs.

Over the woman’s leggings a long blue skirt reaches from her waist nearly to the ground. This, also, is embroidered with beads in a flower pattern. And last, but not least, she wears a bright calico overdress which reaches from her throat to a short distance below her waist, is also beaded, and is gathered in at the belt.

I must not forget to mention her glass necklace, large silver earrings, and the shoulder ornaments of woven grass and beadwork.

She is a graceful woman, and it is pleasant to look at her with the sunset light upon her black hair and eyes.

When her little boy was six years old he was very sick. His cheeks burned with fever. He could not lift his head from the mat on which he lay. His dear mamma scarcely left his side through the long hours of the day. She tried to soothe him with low, sweet songs, but it was in vain. The fever grew stronger and fiercer. Black Cloud came home at night.

Looking at his little son, he said, “The medicine-man must come. He will cure him.”

The medicine-man was at once sent for He is a very important person among the Indians. He is considered very wise. He is thought to have wonderful dreams and to get instruction from the Great Spirit. The red people think he can cure sickness, unless it is the will of the Great Spirit for the patient to die.

The medicine-man always carries a bag of charms to help him in making his cures. I do not doubt you would laugh at the collection in the bag, if you had a chance to peep in, but no good Indian has a thought of doing such a thing It is believed to be holy, and nothing inside should be looked upon except as the medicine-man draws it out to work his cures.

There are medicines, the carved figures of different animals, the bones of others, and I don’t know how many other queer things.

Poor little Yellow Thunder looked up with delight as the great man entered the hut. He believed that he would soon be well and ready to work and play once more.

The medicine-man ordered first that a dog be sacrificed. Next, that the family prepare a great feast for themselves. These things would help to satisfy the Great Spirit and turn away his anger. But this was not all. He took out a rattle from his bag. It was made of the dried hoofs of deer fastened to a stick. He began to sing, beating time with his rattle, and striking himself violent blows. The singing grew louder and louder. The rattle made a fearful din.

How did our poor sick cousin stand it? I’m sure I can’t tell. The little fellow lay with closed eyes and hardly moved. This queer doctor at length stopped his song and got ready to go away. He told Yellow Thunder’s papa that his son would be sure to get well. And you know already from my story that our red cousin did get over his sickness, and grew to be a big, strong boy. Whether the treatment he got was any help, or whether Mother Nature did all the work, I leave you to decide for yourselves. I have my own opinion in the matter.

Yellow Thunder is very fond of music. I wonder what he would think of a church organ or grand piano. His own instruments are very simple. He made them himself. He has a tambourine on which he often plays in the evening while other children dance. He cut a section of wood from a hollow tree and stretched a skin over it, and his instrument was made.

He also has a flute. It was a little more work for the red boy to make this. He carved two pieces of cedar in the shape of half cylinders, and fastened them together with fish glue. He next hunted about in the woods for a snake. After he had found one and killed it, he took off the skin and stretched it over the wood. Eight holes were then made in the instrument, as well as a mouthpiece like that of a flageolet.

When Yellow Thunder blows upon this flute, it makes soft and sweet music. It lay by his side when he was sick with the fever, and as soon as he was strong enough to sit up, he amused himself by playing some simple tunes his mamma had taught him.

Our little friend is very fond of dancing. His people have so many dances that I shall have to tell you about some of them.

They believe the Great Spirit gave them the gift of dancing. They have a Dance for the Dead, a Medicine Dance, the War.. dance, the Dance of Honour, and I don’t know how many others. In some of them only men take part, and they have special costumes, while in others there are none but women. It seems as though there were always something happening among the Indians to give them a good reason to dance.

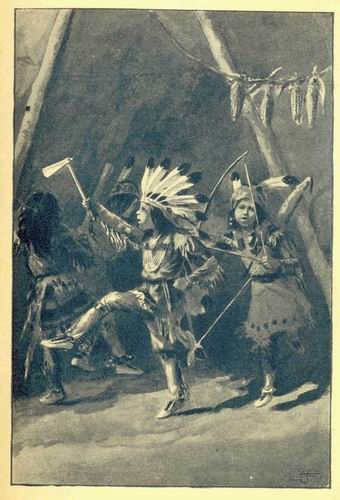

The War-dance is only performed in the evening and always on some important occasion.

Fifteen or twenty men are usually chosen, one of whom must be the leader. All appear in costume and wear knee rattles of deer’s hoofs. When the time draws near, the people gather in the council-house and wait quietly for the dancers to arrive. A keeper-of-the-faith rises and makes a short speech on the meaning of the dance. Hark! The war-whoop sounds outside! It is heard again, and still again. The band is drawing near. Ah! here they come at last.

To our eyes they look hideous in their war-paint and feathers, but to the crowd of eager Indians who are waiting, they appear very fair, indeed.

They march in and form a circle. The war-whoop is sounded again by the leader, and answered by the rest of the dancers. At a given sign, the singers commence the war-song, the drums beat, and the dancers begin to move. They come down on their heels again and again with the greatest force, keeping time to the beating of the drums. The knee rattles make noise enough of themselves. The din is fearful.

The dancers change their positions continually. At the same moment you will see some of them with their arms raised as though to attack, others in the act of drawing the bow, others again appear to be throwing the tomahawk, or striking with the war-club. Every position possible in battle is taken.

Each one is full of the excitement of the moment. The wild music and dancing last for about two minutes. For, the next two minutes the dancers walk around in a circle to the slow beating of the drums. Then there is another war-whoop, which is followed by another dance and song.

The dance is often stopped by a tap upon the ground by one of the audience. He wishes to make a short speech. It, maybe, is a funny one to make everybody laugh. Or perhaps the speaker wishes to inspire the people to nobler lives or to greater love for their race. He can say anything he chooses, on condition that at the end of the speech he makes a present to one of the dancers. This speech gives the dancers a chance to rest, and at the same time keeps the people interested.

The evening is full of entertainment, and passes only too quickly. I’m afraid, however, if you were present you would be more frightened than amused by such wild music and motions.

Another strange dance which is performed among Yellow Thunder’s people is called the Dance for the Dead. Only women take part in it. It is generally given every spring and fall, in honour of those of the tribe who have died. The Indians believe that at these times their dead friends come back and join in the dance.

The music is sad, and the movements of the dancers are slow and mournful. This strange dance is kept up from dusk till the early morning. It is believed that the dead friends who have been present must then go back to the happy hunting-grounds.

I haven’t said very much as yet about our red cousin’s playmates and sports. They have many good times together. They have a great number of games and many matches of strength and quickness.

Yellow Thunder loves his ball game as much as you boys love baseball. He and his friends often prepare for a game by a special diet and training for days beforehand. Crowds gather from neighbouring tribes and villages to see the sport. Those who take part wear no clothing except a waist-cloth. The ball is small and is made of deerskin.

A large open field is chosen, and two gates are made on opposite sides of it. Each gate is made by setting two poles three rods apart. Six or eight boys play on a side and own one of the gates. The game is won by the side which first carries the bail through its own gate a certain number of times. The white men learned this game from the Indians, and it is a great favourite with them in some parts of the country, especially in Canada. It is now called “lacrosse,” but its name in the language of the Iroquois Indians was O-ta-da-jish-qua-age.

Black Cloud has as much interest as Yellow Thunder in the game, and often takes part in it with his friends. You can hardly believe how excited these red men get when they are preparing for a set game of ball.

The javelin game is another of the boy’s favourites. It is quite simple, and yet one needs to be very skilful. Rings about eight inches across, and javelins five or six feet long are needed in playing it. While a ring is set rolling upon the ground by one person, a player on the other side throws the javelin and tries to hit it. If he succeed, the ring is set up as a target, and each one on the opposite side must throw a javelin and try to hit it. If he fail, he loses his javelin. Victory belongs to the side which wins the most javelins.

The favourite game in winter is that of snow snakes. The snakes are made of hickory. They are from five to seven feet long.

The head of the snake is round and pointed with lead. It is about an inch wide and slightly turned up. The snake is made so that it tapers toward the tail, which is only about half an inch wide.

Yellow Thunder has practised so much that he can throw his snake with great skill. It skims along the snow crust like an arrow. He has won many a game this winter and his father is very proud of him, because it takes a great deal of strength and training to be a good player.

There are many other games played by the Indian men and boys, but I shall have to tell you about them some other time.

I hear one of my little friends say: “I wonder if my red cousin has any holidays. He certainly cannot understand the glorious Fourth, and I don’t believe he ever heard of Christmas. How does he get along?”

Why, my dear children, I can’t stop to tell you of all the feasts and festivals to which the boy is invited. On every possible occasion a feast is given by some one in the village. For instance, if the men are very successful in one of their hunts, and come home laden down with a good supply of deer, raccoon, or bear, some one of them prepares a feast.

How you would laugh to see them gathering at a party. Each one carries his own wooden bowl and plate, for that is the custom. I mean that each man does this, for the women are not expected to sit down. They only stand around and laugh at the bright sayings they hear. They must not even join in the conversation. They seem to think that they are having a good time, however, and when the feast is over go back to their own wigwams, repeating to each other the good things they have heard. The men remain to smoke and tell more stories.

Sometimes a feast is prepared on purpose for the young people. At such a time some one who is much older than themselves makes a speech. He encourages his young friends to be nobler, braver, and better than ever before. It seems as though Yellow Thunder could never forget the good words he has heard at these feasts. Whenever he feels like showing pain or being ill-tempered, he recollects them, and they help to keep him calm.

Each season of the year has its special festival. The longest of all is the new year jubilee, which lasts seven days. It takes place in the middle of the winter, about the first of February. Several days before the beginning of the celebration, our little cousin gathers with his people in the council-hall. They must confess their sins to each other before the new year opens. Yellow Thunder thinks over everything which he has done, or not done as he ought, during the past year. He does not wish to forget anything.

When the great day arrives, two keepers-of-the-faith come to his home early in the morning. It is their duty to go to every other wigwam, too. They are dressed up in such a way that Yellow Thunder cannot tell who they are. They wear bear or buffalo skins wrapped around their bodies, and fastened about their heads with wreaths of corn husks. They also wear wreaths of corn husks around their arms and ankles. Their faces are painted in all sorts of queer ways. They carry corn pounders in their hands.

As they enter the hut, they bow to the family, and one of them strikes the ground with his corn pounder. When every one is silent, he makes a speech, urging them to clean their house, put everything in order, and prepare for the festivities of the next few days. If any one in the family should be taken sick and die, he urges them not to mourn till the ceremonies which the Great Spirit has commanded are over. You can see from this that the Indian’s religion is carried into everything he does.

After a song of thanksgiving, the keepers-of-the-faith leave Yellow Thunder’s home and pass on to the next one. In the afternoon they come back again, and urge the family to give thanks to the Great Spirit for the return of the season.

The little boy is most excited on this first day of the festival by the strangling of the White Dog. It must be spotless, if possible. White is the emblem of purity and faith. A white deer or squirrel, or any other animal that is pure white, is thought to be sacred to the Great Spirit.

The dog, which has been carefully kept for this purpose, is killed with the greatest care. Otherwise it would not be a fitting sacrifice. Not a drop of blood must be shed. Not a bone must be broken. When it is quite dead, it is trimmed with ribbons and feathers, and spotted in different places with dabs of red paint. Then it is hung up by its neck on a pole. It must stay there till the fifth day. At that time it will be taken down to be burned.

On the second day, Yellow Thunder is dressed up in his very best, and goes out with his father and mother to make calls on his neighbours. The keepers-of-the-faith come to his house three times during the day. They are now dressed up as warriors with all their war-paint and feathers. One of them stirs up the ashes in the fireplace and sprinkles them about. As he does this, he makes a speech, thanking the Great Spirit that the family, as well as himself, have been allowed to live another year to take part in the festival. There is another song of thanksgiving and they go away.

On the third and fourth days small dancing parties go from home to home. One party will perform the war-dance, another the feather-dance, still another the fish-dance, and so on. This year Yellow Thunder’s father let him join a party of boys to give the war-dance. They had great fun dressing up as warriors and decking themselves with paint and feathers. They went from home to home till they had danced in every hut in the village. They were tired enough to sleep soundly when night came.

I must tell you of some more sport they had during the festival. Some of the boys dressed in rags and paint, put on false faces and formed a “thieving party,” as it was called. They went about collecting things for a feast. An old woman carrying a large basket went with them. If the family they visited made them presents, they handed them to the old woman and gave a dance in return for the kindness. But if no presents were given, they took anything they could seize without being seen. If they were discovered, they gave them up, but if not, it was considered fair for them to carry the things away for their feast.

Yellow Thunder had great fun hiding the stolen articles in his clothing. He was not once caught.

Every night was given up to dancing and other entertainments. Our Indian cousin got time for a game of snow snakes nearly every day.

On the morning of the fifth day the White Dog was burned. A procession was formed, the men marching in Indian file. Listen! A great sound is heard. It is something like the war-whoop. It is the signal to start. The dead dog is carried to the altar on a bark litter in front of the procession. The sacrifice is laid upon the altar. The fire is kindled. As the flames rise, a prayer is made to the Great Spirit for all his good gifts to the Indians. The trees and the bushes, the sun and the winds, the moon and the stars, — none are forgotten that have helped to make the world. better to live in.

As the sacrifice burns upon the altar, Yellow Thunder listens to the long prayer with reverence. He believes that the dog’s soul is now rising to the Great Spirit. It will be a proof to Him of the faith of His people, for the day itself is the day of faith and trust.

During the rest of the festival there is more dancing and more feasting, while favourite games are played by old and young.

“Oh, what a good time it is,” thinks Yellow Thunder; “how happy we all should be that the new year has come.” And what a tired boy sleeps on Yellow Thunder’s mat when the seven days of this glorious time are over. The Fourth of July celebration is slight indeed compared with it.

Yellow Thunder begins already to look forward to the first festival of the springtime. It is called by the Indians “Thanks to the Mar le.” I don’t dare to give it to you in their own language. You would only scowl and say, “Oh, dear! what’s the use? I can’t pronounce those long words, and I will not try.”

Just as soon as the first warm days arrive, the red boy’s eyes begin to watch the maple-trees. He wishes to be the first one to discover that the sap has started and is beginning to flow. Then hurrah for a holiday for old and young! Thanks must be given to the tree that gives so much sweetness to boys and girls. The Great Spirit must be thanked, also, for he gave the maple to the poor Indian.

There must be more feasting and storytelling, more games and dancing. Tobacco must be burned as an offering to the Great Spirit, and prayers must be said. The great feather dance will be the best thing of all. It is very graceful and beautiful, and the band of dancers will wear costumes which belong only to this dance.

You certainly cannot wonder that Yellow Thunder enjoys this festival. I don’t doubt you would like to be there, also, as well as at the green corn feast, and many others.

At these times your red cousin’s heart is full of gladness and gratitude for the great gifts the Great Spirit has given him.

It is evening time. Let us creep up softly behind him as he listens to a legend one of the story-tellers of the tribe is repeating. It is the tale of the Lone Lightning.

Once upon a time there was a poor little boy who had no father or mother. He lived with an uncle who did not love him. This cruel man made the child do many hard things and did not give him enough to eat.

Of course the child did not grow properly. He was very thin and pitiful to look upon. After awhile the cruel uncle grew ashamed of the appearance of the boy. Every one could see that he was ill-treated.

He said to himself, “I will give the child so much to eat that he will die. I hate him!” Then he went to his wife and said, “Give the boy bear’s meat, and choose the fat of it for him.”

They kept cramming the child. When they were stuffing the food down his throat one day, he almost choked. Poor little fellow! There was no one who cared for him or wished him to live. He knew it only too well.

The first chance he obtained, he ran away. He did not know where to go, but wandered around in the forest. Night came. Wild beasts would now begin to roam about. They would get him and eat him. The little boy was afraid when he thought of all this. He climbed up in a tree as far as he dared, and went to sleep in a fork of the branches. He had a wonderful dream. It was an omen given to him by the spirits.

It seemed as though some one appeared to him from out of the sky. He spoke to the orphan.. and said, “Poor child, I know all about your hard life and your cruel uncle. Come with me.”

The boy awoke instantly. There was his guide. He began to follow him. Higher and higher he rose up in the air till they were both in the upper sky. Then his guide placed twelve arrows in his hands and told him that there were many bad manitos (spirits) in the northern sky. He must go forth and try to shoot them.

He did as he was told. He travelled toward the north and shot one arrow after another, vainly trying to kill the manitos. He now had only one arrow left. As each one had sped forth from his bow, there had been a long streak of lightning in the sky. Then all had grown clear again.

The boy held the last arrow in his hand for a long time and tried again to discover the manitos. But these beings are very cunning if they choose, and they can change their forms at any moment. They were afraid of the boy’s arrows, for they had magic powers and had been given him by a good spirit. If the child aimed them straight, the bad manitos would be killed.

At length the boy gained courage and shot his last arrow. He thought it was aimed at the very heart of the chief of the spirits. But before it reached him, he had changed himself into a rock. The head of the arrow pierced this rock and fastened itself within it.

The manito was enraged. He cried out, “Your arrows are gone now. You shall be punished for daring to strike at me.” As he said these words, he changed the boy into the Lone Lightning, which is still seen in the northern sky to this day.

THE END.

copyright, Kellscraft Studio1999-2003

Return to Web Text-ures Content Page