| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

|

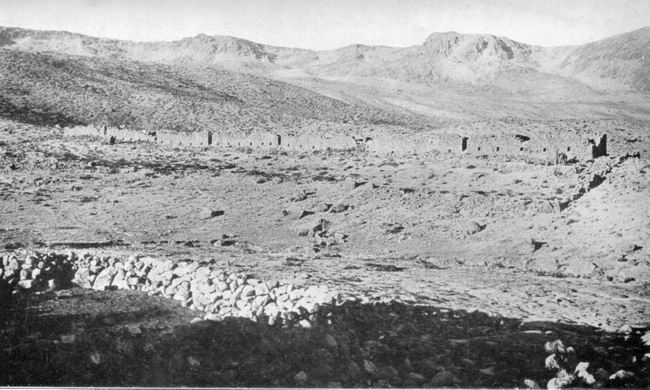

CHAPTER III TO PARINACOCHAS AFTER a few days in the delightful climate of Chuquibamba we set out for Parinacochas, the “Flamingo Lake” of the Incas. The late Sir Clements Markham, literary and historical successor of the author of “The Conquest of Peru,” had called attention to this unexplored lake in one of the publications of the Royal Geographical Society, and had named a bathymetric survey of Parinacochas as one of the principal desiderata for future exploration in Peru. So far as one could judge from the published maps Parinacochas, although much smaller than Titicaca, was the largest body of water entirely in Peru. A thorough search of geographical literature failed to reveal anything regarding its depth. The only thing that seemed to be known about it was that it had no outlet. General William Miller, once British consul general in Honolulu, who had as a young man assisted General San Martin in the Wars for the Independence of Chile and Peru, published his memoirs in London in 1828. During the campaigns against the Spanish forces in Peru he had had occasion to see many out-of-the-way places in the interior. On one of his rough sketch maps he indicates the location of Lake Parinacochas and notes the fact that the water is “brackish.” This statement of General Miller’s and the suggestion of Sir Clements Markham that a bathymetric survey of the lake would be an important contribution to geographical knowledge was all that we were able to learn. Our arrieros, the Tejadas, had never been to Parinacochas, but knew in a general way its location and were not afraid to try to get there. Some of their friends had been there and come back alive! First, however, it was necessary for us to go to Cotahuasi, the capital of the Province of Antabamba, and meet Dr. Bowman and Mr. Hendriksen, who had slowly been working their way across the Andes from the Urubamba Valley, and who would need a new supply of food-boxes if they were to complete the geographical reconnaissance of the 73d meridian. Our route led us out of the Chuquibamba Valley by a long, hard climb up the steep cliffs at its head and then over the gently sloping, semi-arid desert in a northerly direction, around the west flanks of Coropuna. When we stopped to make camp that night on the Pampa of Chumpillo, our arrieros used dried moss and dung for fuel for the camp fire. There was some bunch-grass, and there were llamas pasturing on the plains. Near our tent were some Inca ruins, probably the dwelling of a shepherd chief, or possibly the remains of a temple described by Cieza de Leon (1519-1560), whose remarkable accounts of what he saw and learned in Peru during the time of the Pizarros are very highly regarded. He says that among the five most important temples in the Land of the Incas was one “much venerated and frequented by them, named Coropuna.” “It is on a very lofty mountain which is covered with snow both in summer and winter. The kings of Peru visited this temple making presents and offerings.... It is held for certain [by treasure hunters!] that among the gifts offered to this temple there were many loads of silver, gold, and precious stones buried in places which are now unknown. The Indians concealed another great sum which was for the service of the idol, and of the priests and virgins who attended upon it. But as there are great masses of snow, people do not ascend to the summit, nor is it known where these are hidden. This temple possessed many flocks, farms, and service of Indians.” No one lives here now, but there are many flocks and llamas, and not far away we saw ancient storehouses and burial places. That night we suffered from intense cold and were kept awake by the bitter wind which swept down from the snow fields of Coropuna and shook the walls of our tent violently. The next day we crossed two small oases, little gulches watered from the melting snow of Coropuna. Here there was an abundance of peat and some small gnarled trees from which Chuquibamba derives part of its fuel supply. We climbed slowly around the lower spurs of Coropuna into a bleak desert wilderness of lava blocks and scoriaceous sand, the Red Desert, or Pampa Colorada. It is for the most part between 15,000 and 16,000 feet above sea level, and is bounded on the northwest by the canyon of the Rio Arma, 2000 feet deep, where we made our camp and passed a more agreeable night. The following morning we climbed out again on the farther side of the canyon and skirted the eastern slopes of Mt. Solimana. Soon the trail turned abruptly to the left, away from our old friend Coropuna. We wondered how long ago our mountain was an active volcano. To-day, less than two hundred miles south of here are live peaks, like El Misti and Ubinas, which still smolder occasionally and have been known in the memory of man to give forth great showers of cinders covering a wide area. Possibly not so very long ago the great truncated peak of Coropuna was formed by a last flickering of the ancient fires. Dr. Bowman says that the greater part of the vast accumulation of lavas and volcanic cinders in this vicinity goes far back to a period preceding the last glacial epoch. The enormous amount of erosion that has taken place in the adjacent canyons and the great numbers of strata, composed of lava flows, laid bare by the mighty streams of the glacial period all point to this conclusion. My saddle mule was one of those cantankerous beasts that are gentle enough as long as they are allowed to have their own way. In her case this meant that she was happy only when going along close to her friends in the caravan. If reined in, while I took some notes, she became very restive, finally whirling around, plunging and kicking. Contrariwise, no amount of spurring or lashing with a stout quirt availed to make her go ahead of her comrades. This morning I was particularly anxious to get a picture of our pack train jogging steadily along over the desert, directly away from Coropuna. Since my mule would not gallop ahead, I had to dismount, run a couple of hundred yards ahead of the rapidly advancing animals and take the picture before they reached me. We were now at an elevation of 16,000 feet above sea level. Yet to my surprise and delight I found that it was relatively as easy to run here as anywhere, so accustomed had my lungs and heart become to very rarefied air. Had I attempted such a strenuous feat at a similar altitude before climbing Coropuna it would have been physically impossible. Any one who has tried to run two hundred yards at three miles above sea level will understand. We were still in a very arid region; mostly coarse black sand and pebbles, with typical desert shrubs and occasional bunches of tough grass. The slopes of Mt. Solimana on our left were fairly well covered with sparse vegetation. Among the bushes we saw a number of vicuņas, the smallest wild camels of the New World. We tried in vain to get near enough for a photograph. They were extremely timid and scampered away before we were within three hundred yards. Seven or eight miles more of very gradual downward slope brought us suddenly and unexpectedly to the brink of a magnificent canyon, the densely populated valley of Cotahuasi. The walls of the canyon were covered with innumerable terraces — thousands of them. It seemed at first glance as though every available spot in the canyon had been either terraced or allotted to some compact little village. One could count more than a score of towns, including Cotahuasi itself, its long main street outlined by whitewashed houses. As we zigzagged down into the canyon our road led us past hundreds of the artificial terraces and through little villages of thatched huts huddled together on spurs rescued from the all-embracing agriculture. After spending several weeks in a desert region, where only the narrow valley bottoms showed any signs of cultivation, it seemed marvelous to observe the extent to which terracing had been carried on the side of the Cotahuasi Valley. Although we were now in the zone of light annual rains, it was evident from the extraordinary irrigation system that agriculture here depends very largely on ability to bring water down from the great mountains in the interior. Most of the terraces and irrigation canals were built centuries ago, long before the discovery of America. No part of the ancient civilization of Peru has been more admired than the development of agriculture. Mr. Cook says that there is no part of the world in which more pains have been taken to raise crops where nature made it hard for them to be planted. In other countries, to be sure, we find reclamation projects, where irrigation canals serve to bring water long distances to be used on arid but fruitful soil. We also find great fertilizer factories turning out, according to proper chemical formula, the needed constituents to furnish impoverished soils with the necessary materials for plant growth. We find man overcoming many obstacles in the way of transportation, in order to reach great regions where nature has provided fertile fields and made it easy to raise life-giving crops. Nowhere outside of Peru, either in historic or prehistoric times, does one find farmers spending incredible amounts of labor in actually creating arable fields, besides bringing the water to irrigate them and the guano to fertilize them; yet that is what was done by the ancient highlanders of Peru. As they spread over a country in which the arable flat land was usually at so great an elevation as to be suitable for only the hardiest of root crops, like the white potato and the oca, they were driven to use narrow valley bottoms and steep, though fertile, slopes in order to raise the precious maize and many of the other temperate and tropical plants which they domesticated for food and medicinal purposes. They were constantly confronted by an extraordinary scarcity of soil. In the valley bottoms torrential rivers, meandering from side to side, were engaged in an endless endeavor to tear away the arable land and bear it off to the sea. The slopes of the valleys were frequently so very steep as to discourage the most ardent modern agriculturalist. The farmer might wake up any morning to find that a heavy rain during the night had washed away a large part of his carefully planted fields. Consequently there was developed, through the centuries, a series of stone-faced andenes, terraces or platforms. Examination of the ancient andenes discloses the fact that they were not made by simply hoeing in the earth from the hillside back of a carefully constructed stone wall. The space back of the walls was first filled in with coarse rocks, clay, and rubble; then followed smaller rocks, pebbles, and gravel, which would serve to drain the subsoil. Finally, on top of all this, and to a depth of eighteen inches or so, was laid the finest soil they could procure. The result was the best possible field for intensive cultivation. It seems absolutely unbelievable that such an immense amount of pains should have been taken for such relatively small results. The need must have been very great. In many cases the terraces are only a few feet wide, although hundreds of yards in length. Usually they follow the natural contours of the valley. Sometimes they are two hundred yards wide and a quarter of a mile long. To-day corn, barley, and alfalfa are grown on the terraces. Cotahuasi itself lies in the bottom of the valley, a pleasant place where one can purchase the most fragrant and highly prized of all Peruvian wines. The climate is agreeable, and has attracted many landlords, whose estates lie chiefly on the bleak plateaus of the surrounding highlands, where shepherds tend flocks of llamas, sheep, and alpacas. We were cordially welcomed by Seņor Viscarra, the sub-prefect, and invited to stay at his house. He was a stranger to the locality, and, as the visible representative of a powerful and far-away central government, was none too popular with some of the people of his province. Very few residents of a provincial capital like Cotahuasi have ever been to Lima; — probably not a single member of the Lima government had ever been to Cotahuasi. Consequently one could not expect to find much sympathy between the two. The difficulties of traveling in Peru are so great as to discourage pleasure trips. With our letters of introduction and the telegrams that had preceded us from the prefect at Arequipa, we were known to be friends of the government and so were doubly welcome to the sub-prefect. By nature a kind and generous man, of more than usual education and intelligence, Seņor Viscarra showed himself most courteous and hospitable to us in every particular. In our honor he called together his friends. They brought pictures of Theodore Roosevelt and Elihu Root, and made a large American flag; a courtesy we deeply appreciated, even if the flag did have only thirty-six stars. Finally, they gave us a splendid banquet as a tribute of friendship for America. One day the sub-prefect offered to have his personal barber attend us. It was some time since Mr. Tucker and I had seen a barber-shop. The chances were that we should find none at Parinacochas. Consequently we accepted with pleasure. When the barber arrived, closely guarded by a gendarme armed with a loaded rifle, we learned that he was a convict from the local jail! I did not like to ask the nature of his crime, but he looked like a murderer. When he unwrapped an ancient pair of clippers from an unspeakably soiled and oily rag, I wished I was in a position to decline to place myself under his ministrations. The sub-prefect, however, had been so kind and was so apologetic as to the inconveniences of the “barber-shop” that there was nothing for it but to go bravely forward. Although it was unpleasant to have one’s hair trimmed by an uncertain pair of rusty clippers, I could not help experiencing a feeling of relief that the convict did not have a pair of shears. He was working too near my jugular vein. Finally the period of torture came to an end, and the prisoner accepted his fees with a profound salutation. We breathed sighs of relief, not unmixed with sympathy, as we saw him marched safely away by the gendarme. We had arrived in Cotahuasi almost simultaneously with Dr. Bowman and Topographer Hendriksen. They had encountered extraordinary difficulties in carrying out the reconnaissance of the 73d meridian, but were now past the worst of it. Their supplies were exhausted, so those which we had brought from Arequipa were doubly welcome. Mr. Watkins was assigned to assist Mr. Hendriksen and a few days later Dr. Bowman started south to study the geology and geography of the desert. He took with him as escort Corporal Gamarra, who was only too glad to escape from the machinations of his enemies. It will be remembered that it was Gamarra who had successfully defended the Cotahuasi barracks and jail at the time of a revolutionary riot which occurred some months previous to our visit. The sub-prefect accompanied Dr. Bowman out of town. For Gamarra’s sake they left the house at three o’clock in the morning and our generous host agreed to ride with them until daybreak. In his important monograph, “The Andes of Southern Peru,” Dr. Bowman writes: “At four o’clock our whispered arrangements were made. We opened the gates noiselessly and our small cavalcade hurried through the pitch-black streets of the town. The soldier rode ahead, his rifle across his saddle, and directly behind him rode the sub-prefect and myself. The pack mules were in the rear. We had almost reached the end of the street when a door opened suddenly and a shower of sparks flew out ahead of us. Instantly the soldier struck spurs into his mule and turned into a side street. The sub-prefect drew his horse back savagely, and when the next shower of sparks flew out pushed me against the wall and whispered, ‘For God’s sake, who is it?’ Then suddenly he shouted, ‘Stop blowing! Stop blowing!’” The cause of all the disturbance was a shabby, hard-working tailor who had gotten up at this unearthly hour to start his day’s work by pressing clothes for some insistent customer. He had in his hand an ancient smoothing-iron filled with live coals, on which he had been vigorously blowing. Hence the sparks! That a penitent tailor and his ancient goose should have been able to cause such terrific excitement at that hour in the morning would have interested our own Oliver Wendell Holmes, who was fond of referring to this picturesque apparatus and who might have written an appropriate essay on The Goose that Startled the Soldier of Cotahuasi; with Particular Reference to His Being a Possible Namesake of the Geese that Aroused the Soldiers of Ancient Rome.  THE SUB-PREFECT OF COTAHUASI, HIS MILITARY AIDE, AND MESSRS. TUCKER, HENDRIKSEN, BOWMAN, AND BINGHAM INSPECTING THE LOCAL RUG-WEAVING INDUSTRY The most unusual industry of Cotahuasi is the weaving of rugs and carpets on vertical hand looms. The local carpet weavers make the warp and woof of woolen yarn in which loops of alpaca wool, black, gray, or white, are inserted to form the desired pattern. The loops are cut so as to form a deep pile. The result is a delightfully thick, warm, gray rug. Ordinarily the native Peruvian rug has no pile. Probably the industry was brought from Europe by some Spaniard centuries ago. It seems to be restricted to this remote region. The rug makers are a small group of Indians who live outside the town but who carry their hand looms from house to house, as required. It is the custom for the person who desires a rug to buy the wool, supply the pattern, furnish the weaver with board, lodging, coca, tobacco and wine, and watch the rug grow from day to day under the shelter of his own roof. The rug weavers are very clever in copying new patterns. Through the courtesy of Seņor Viscarra we eventually received several small rugs, woven especially for us from monogram designs drawn by Mr. Hendriksen. Early one morning in November we said good-bye to our friendly host, and, directed by a picturesque old guide who said he knew the road to Parinacochas, we left Cotahuasi. The highway crossed the neighboring stream on a treacherous-looking bridge, the central pier of which was built of the crudest kind of masonry piled on top of a gigantic boulder in midstream. The main arch of the bridge consisted of two long logs across which had been thrown a quantity of brush held down by earth and stones. There was no rail on either side, but our mules had crossed bridges of this type before and made little trouble. On the northern side of the valley we rode through a compact little town called Mungi and began to climb out of the canyon, passing hundreds of very fine artificial terraces, at present used for crops of maize and barley. In one place our road led us by a little waterfall, an altogether surprising and unexpected phenomenon in this arid region. Investigation, however, proved that it was artificial, as well as the fields. Its presence may be due to a temporary connection between the upper and lower levels of ancient irrigation canals. Hour after hour our pack train painfully climbed the narrow, rocky zigzag trail. The climate is favorable for agriculture. Wherever the sides of the canyon were not absolutely precipitous, stone-faced terraces and irrigation had transformed them long ago into arable fields. Four thousand feet above the valley floor we came to a very fine series of beautiful terraces. On a shelf near the top of the canyon we pitched our tent near some rough stone corrals used by shepherds whose flocks grazed on the lofty plateau beyond, and near a tiny brook, which was partly frozen over the next morning. Our camp was at an elevation of 14,500 feet above the sea. Near by were turreted rocks, curious results of wind-and-sand erosion. The next day we entered a region of mountain pastures. We passed occasional swamps and little pools of snow water. From one of these we turned and looked back across the great Cotahuasi Canyon, to the glaciers of Solimana and snow-clad Coropuna, now growing fainter and fainter as we went toward Parinacochas. At an altitude of 16,500 feet we struck across a great barren plateau covered with rocks and sand-hardly a living thing in sight. In the midst of it we came to a beautiful lake, but it was not Parinacochas. On the plateau it was intensely cold. Occasionally I dismounted and jogged along beside my mule in order to keep warm. Again I noticed that as the result of my experiences on Coropuna I suffered no discomfort, nor any symptoms of mountain-sickness, even after trotting steadily for four or five hundred yards. In the afternoon we began to descend from the plateau toward Lampa and found ourselves in the pasture lands of Ajochiucha, where ichu grass and other little foliage plants, watered by rain and snow, furnish forage for large flocks of sheep, llamas, and alpacas. Their owners live in the cultivated valleys, but the Indian herdsmen must face the storms and piercing winds of the high pastures. Alpacas are usually timid. On this occasion, however, possibly because they were thirsty and were seeking water holes in the upper courses of a little swale, they stopped and allowed me to observe them closely. The fleece of the alpaca is one of the softest in the world. However, due to the fact that shrewd tradesmen, finding that the fabric manufactured from alpaca wool was highly desired, many years ago gave the name to a far cheaper fabric, the “alpaca” of commerce, a material used for coat linings, umbrellas, and thin, warm-weather coats, is a fabric of cotton and wool, with a hard surface, and generally dyed black. It usually contains no real alpaca wool at all, and is fairly cheap. The real alpaca wool which comes into the market to-day is not so called. Long and silky, straighter than the sheep’s wool, it is strong, small of fiber, very soft, pliable and elastic. It is capable of being woven into fabrics of great beauty and comfort. Many of the silky, fluffy, knitted garments that command the highest prices for winter wear, and which are called by various names, such as “vicuņa,” “camel’s hair,” etc., are really made of alpaca. The alpaca, like its cousin, the llama, was probably domesticated by the early Peruvians from the wild guanaco, largest of the camels of the New World. The guanaco still exists in a wild state and is always of uniform coloration. Llamas and alpacas are extremely variegated. The llama has so coarse a hair that it is seldom woven into cloth for wearing apparel, although heavy blankets made from it are in use by the natives. Bred to be a beast of burden, the llama is accustomed to the presence of strangers and is not any more timid of them than our horses and cows. The alpaca, however, requiring better and scarcer forage — short, tender grass and plenty of water — frequents the most remote and lofty of the mountain pastures, is handled only when the fleece is removed, seldom sees any one except the peaceful shepherds, and is extremely shy of strangers, although not nearly as timid as its distant cousin the vicuņa. I shall never forget the first time I ever saw some alpacas. They looked for all the world like the “woolly-dogs” of our toys shops — woolly along the neck right up to the eyes and woolly along the legs right down to the invisible wheels! There was something inexpressibly comic about these long-legged animals. They look like toys on wheels, but actually they can gallop like cows. The llama, with far less hair on head, neck, and legs, is also amusing, but in a different way. His expression is haughty and supercilious in the extreme. He usually looks as though his presence near one is due to circumstances over which he really had no control. Pride of race and excessive haughtiness lead him to carry his head so high and his neck so stiffly erect that he can be corralled, with others of his kind, by a single rope passed around the necks of the entire group. Yet he can be bought for ten dollars. On the pasture lands of Ajochiucha there were many ewes and lambs, both of llamas and alpacas. Even the shepherds were mostly children, more timid than their charges. They crouched inconspicuously behind rocks and shrubs, endeavoring to escape our notice. About five o’clock in the afternoon, on a dry pampa, we found the ruins of one of the largest known Inca storehouses, Chichipampa, an interesting reminder of the days when benevolent despots ruled the Andes and, like the Pharaohs of old, provided against possible famine. The locality is not occupied, yet near by are populous valleys. As soon as we left our camp the next morning, we came abruptly to the edge of the Lampa Valley. This was another of the mile-deep canyons so characteristic of this region. Our pack mules grunted and groaned as they picked their way down the corkscrew trail. It overhangs the mud-colored Indian town of Colta, a rather scattered collection of a hundred or more huts. Here again, as in the Cotahuasi Valley, are hundreds of ancient terraces, extending for thousands of feet up the sides of the canyon. Many of them were badly out of repair, but those near Colta were still being used for raising crops of corn, potatoes, and barley. The uncultivated spots were covered with cacti, thorn bushes, and the gnarled, stunted trees of a semi-arid region. In the town itself were half a dozen specimens of the Australian eucalyptus, that agreeable and extraordinarily successful colonist which one encounters not only in the heart of Peru, but in the Andes of Colombia and the new forest preserves of California and the Hawaiian Islands.  INCA STOREHOUSES AT CHICHIPAMPA, NEAR COLTA Colta has a few two-storied houses, with tiled roofs. Some of them have open verandas on the second floor — a sure indication that the climate is at times comfortable. Their walls are built of sun-dried adobe, and so are the walls of the little grass-thatched huts of the majority. Judging by the rather irregular plan of the streets and the great number of terraces in and around town, one may conclude that Colta goes far back of the sixteenth century and the days of the Spanish Conquest, as indeed do most Peruvian towns. The cities of Lima and Arequipa are noteworthy exceptions. Leaving Colta, we wound around the base of the projecting ridge, on the sides of which were many evidences of ancient culture, and came into the valley of Huancahuanca, a large arid canyon. The guide said that we were nearing Parinacochas. Not many miles away, across two canyons, was a snow-capped peak, Sarasara. Lampa, the chief town in the Huancahuanca Canyon, lies on a great natural terrace of gravel and alluvium more than a thousand feet above the river. Part of the terrace seemed to be irrigated and under cultivation. It was proposed by the energetic farmers at the time of our visit to enlarge the system of irrigation so as to enable them to cultivate a larger part of the pampa on which they lived. In fact, the new irrigation scheme was actually in process of being carried out and has probably long since been completed. Our reception in Lampa was not cordial. It will be remembered that our military escort, Corporal Gamarra, had gone back to Arequipa with Dr. Bowman. Our two excellent arrieros, the Tejada brothers, declared they preferred to travel without any “brass buttons,” so we had not asked the sub-prefect of Cotahuasi to send one of his small handful of gendarmes along with us. Probably this was a mistake. Unless one is traveling in Peru on some easily understood matter, such as prospecting for mines or representing one of the great importing and commission houses, or actually peddling goods, one cannot help arousing the natural suspicions of a people to whom traveling on mule-back for pleasure is unthinkable, and scientific exploration for its own sake is incomprehensible. Of course, if the explorers arrive accompanied by a gendarme it is perfectly evident that the enterprise has the approval and probably the financial backing of the government. It is surmised that the explorers are well paid, and what would be otherwise inconceivable becomes merely one of the ordinary experiences of life. South American governments almost without exception are paternalistic, and their citizens are led to expect that all measures connected with research, whether it be scientific, economic, or social, are to be conducted by the government and paid for out of the national treasury. Individual enterprise is not encouraged. During all my preceding exploration in Peru I had had such an easy time that I not only forgot, but failed to realize, how often an ever-present gendarme, provided through the courtesy of President Leguia’s government, had quieted suspicions and assured us a cordial welcome. Now, however, when without a gendarme we entered the smart little town of Lampa, we found ourselves immediately and unquestionably the objects of extreme suspicion and distrust. Yet we could not help admiring the well-swept streets, freshly whitewashed houses, and general air of prosperity and enterprise. The gobernador of the town lived on the main street in a red-tiled house, whose courtyard and colonnade were probably two hundred years old. He had heard nothing of our undertaking from the government. His friends urged him to take some hostile action. Fortunately, our arrieros, respectable men of high grade, although strangers in Lampa, were able to allay his suspicions temporarily. We were not placed under arrest, although I am sure his action was not approved by the very suspicious town councilors, who found it far easier to suggest reasons for our being fugitives from justice than to understand the real object of our journey. The very fact that we were bound for Lake Parinacochas, a place well known in Lampa, added to their suspicion. It seems that Lampa is famous for its weavers, who utilize the wool of the countless herds of sheep, alpacas, and vicuņas in this vicinity to make ponchos and blankets of high grade, much desired not only in this locality but even in Arequipa. These are marketed, as so often happens in the outlying parts of the world, at a great annual fair, attended by traders who come hundreds of miles, bringing the manufactured articles of the outer world and seeking the highly desired products of these secluded towns. The great fair for this vicinity has been held, for untold generations, on the shores of Lake Parinacochas. Every one is anxious to attend the fair, which is an occasion for seeing one’s friends, an opportunity for jollification, carousing, and general enjoyment — like a large county fair at home. Except for this annual fair week, the basin of Parinacochas is as bleak and desolate as our own fair-grounds, with scarcely a house to be seen except those that are used for the purposes of the fair. Had we been bound for Parinacochas at the proper season nothing could have been more reasonable and praiseworthy. Why anybody should want to go to Parinacochas during one of the other fifty-one weeks in the year was utterly beyond the comprehension or understanding of these village worthies. So, to our “selectmen,” are the idiosyncrasies of itinerant gypsies who wish to camp in our deserted fair-grounds. The Tejadas were not anxious to spend the night in town — probably because, according to our contract, the cost of feeding the mules devolved entirely upon them and fodder is always far more expensive in town than in the country. It was just as well for us that this was so, for I am sure that before morning the village gossips would have persuaded the gobernador to arrest us. As it was, however, he was pleasant and hospitable, and considerably amused at the embarrassment of an Indian woman who was weaving at a hand loom in his courtyard and whom we desired to photograph. She could not easily escape, for she was sitting on the ground with one end of the loom fastened around her waist, the other end tied to a eucalyptus tree. So she covered her eyes and mouth with her hands, and almost wept with mortification at our strange procedure. Peruvian Indian women are invariably extremely shy, rarely like to be photographed, and are anxious only to escape observation and notice. The ladies of the gobernador’s own family, however, of mixed Spanish and Indian ancestry, not only had no objection to being photographed, but were moved to unseemly and unsympathetic laughter at the predicament of their unfortunate sister. After leaving Lampa we found ourselves on the best road that we had seen in a long time. Its excellence was undoubtedly due to the enterprise and energy of the people of this pleasant town. One might expect that citizens who kept their town so clean and neat and were engaged in the unusual act of constructing new irrigation works would have a comfortable road in the direction toward which they usually would wish to go, namely, toward the coast. As we climbed out of the Huancahuanca Valley we noticed no evidences of ancient agricultural terraces, either on the sides of the valley or on the alluvial plain which has given rise to the town of Lampa and whose products have made its people well fed and energetic. The town itself seems to be of modern origin. One wonders why there are so few, if any, evidences of the ancient regime when there are so many a short distance away in Colta and the valley around it. One cannot believe that the Incas would have overlooked such a tine agricultural opportunity as an extensive alluvial terrace in a region where there is so little arable land. Possibly the very excellence of the land and its relative flatness rendered artificial terracing unnecessary in the minds of the ancient people who lived here. On the other hand, it may have been occupied until late Inca times by one of the coast tribes. Whatever the cause, certainly the deep canyon of Huancahuanca divides two very different regions. To come in a few hours, from thickly terraced Colta to unterraced Lampa was so striking as to give us cause for thought and speculation. It is well known that in the early days before the Inca conquest of Peru, not so very long before the Spanish Conquest, there were marked differences between the tribes who inhabited the high plateau and those who lived along the shore of the Pacific. Their pottery is as different as possible in design and ornamentation; the architecture of their cities and temples is absolutely distinct. Relative abundance of flat lands never led them to develop terracing to the same extent that the mountain people had done. Perhaps on this alluvial terrace there lived a remnant of the coastal peoples. Excavation would show. Scarcely had we climbed out of the valley of Huancahuanca and surmounted the ridge when we came in sight of more artificial terraces. Beyond a broad, deep valley rose the extinct volcanic cone of Mt. Sarasara, now relatively close at hand, its lower slopes separated from us by another canyon. Snow lay in the gulches and ravines near the top of the mountain. Our road ran near the towns of Pararca and Colcabamba, the latter much like Colta, a straggling village of thatched huts surrounded by hundreds of terraces. The vegetation on the valley slopes indicated occasional rains. Near Pararca we passed fields of barley and wheat growing on old stone-faced terraces. On every hand were signs of a fairly large population engaged in agriculture, utilizing fields which had been carefully prepared for them by their ancestors. They were not using all, however. We noticed hundreds of terraces that did not appear to have been under cultivation recently. They may have been lying fallow temporarily. Our arrieros avoided the little towns, and selected a camp site on the roadside near the Finca Rodadero. After all, when one has a comfortable tent, good food, and skillful arrieros it is far pleasanter to spend the night in the clean, open country, even at an elevation of 12,000 or 13,000 feet, than to be surrounded by the smells and noises of an Indian town. The next morning we went through some wheat fields, past the town of Puyusca, another large Indian village of thatched adobe house, placed high on the shoulder of a rocky hill so as to leave the best arable land available for agriculture. It is in a shallow, well-watered valley, full of springs. The appearance of the country had changed entirely since we left Cotahuasi. The desert and its steep-walled canyons seemed to be far behind us. Here was a region of gently sloping hills, covered with terraces, where the cereals of the temperate zone appeared to be easily grown. Finally, leaving the grain fields, we climbed up to a shallow depression in the low range at the head of the valley and found ourselves on the rim of a great upland basin more than twenty miles across. In the center of the basin was a large, oval lake. Its borders were pink. The water in most of the lake was dark blue, but near the shore the water was pink, a light salmon-link. What could give it such a curious color? Nothing but flamingoes, countless thousands of flamingoes — Parinacochas at last! |