| Web

and Book

design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return

to Web

Text-ures)

|

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER I WITH THE TZIGANES Banda

Bela,

the little Gypsy boy, had tramped

all day through the hills, until, footsore, weary, and discouraged, he

was

ready to throw himself down to sleep. He was very hungry, too. "I shall go to

the next hilltop

and perhaps there is a road, and some passerby will throw me a crust.

If not, I

can feed upon my music and sleep," he thought to himself, as he

clambered

through the bushes to the top of the hill. There he stood, his old

violin held

tight in his scrawny hand, his ragged little figure silhouetted against

the

sky. Through the

central part of Hungary

flows in rippling beauty the great river of the Danube. Near to Kecskés

the

river makes a sudden bend, the hills grow sharper in outline, while to

the

south and west sweep the great grass plains. Before Banda

Bela, like a soft green

sea, the Magyar plain stretched away until it joined the horizon in a

dim line.

Its green seas of grain were cut only by the tall poplar trees which

stood like

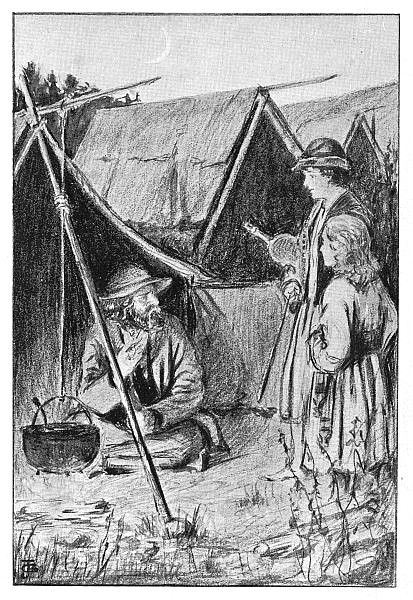

sentinels against the sky. Beside these was pitched a Gypsy camp, its

few tents

and huts huddled together, looking dreary and forlorn in the dim

twilight. The

little hovels were built of bricks and stones and a bit of thatch,

carelessly

built to remain only until the wander spirit rose again in their

breasts and

the Gypsies went forth to roam the green velvet plain, or float down

the Danube

in their battered old boats, lazily happy in the sun. In front of the

largest hut was the

fire-pot, slung from a pole over a fire of sticks burning brightly. The

Gypsies

were gathered about the fire for their evening meal, and the scent of goulash came from the kettle. Banda Bela

could hardly stand from faintness, but he raised his violin to his

wizened chin

and struck a long chord. As the fine tone of the old violin smote the

night

air, the Gypsies ceased talking and looked up. Unconscious of their

scrutiny,

the boy played a czardas, weird and

strange. At first there was a cool, sad strain like the night song of

some

bird, full of the gentle sadness of those without a home, without

friends, yet

not without kindness; then the time changed, grew quicker and quicker

until it

seemed as if the old violin danced itself, so full of wild Gypsy melody

were

its strains. Fuller and fuller they rose; the bow in the boy's fingers

seeming

to skim like a bird over the strings. The music, full of wild longing,

swelled

until its voice rose like the wild scream of some forest creature, then

crashed

to a full stop. The violin dropped to the boy's side, his eyes closed,

and he

fell heavily to the ground. When Banda Bela

opened his eyes he

found himself lying upon the ground beside the Gypsy fire, his head

upon a

bundle of rags. The first thing his eyes fell upon was a little girl

about six

years old, who was trying to put into his mouth a bit of bread soaked

in gravy.

The child was dressed only in a calico frock, her head was uncovered,

her hair,

not straight and black like that of the other children who swarmed

about, but

light as corn silk, hung loosely about her face. Her skin was as dark

as sun

and wind make the Tziganes, but the eyes which looked into his with a

gentle

pity were large and deep and blue. "Who are you?"

he asked,

half conscious. "Marushka," she

answered

simply. "What is your name?" "Banda Bela,"

he said

faintly. "Why do you

play like the

summer rain on the tent?" she demanded. "Because the

rain is from

heaven on all the Tziganes, and it is good, whether one lies snug

within the

tent or lifts the face to the drops upon the heath." "I like you,

Banda Bela,"

said little Marushka. "Stay with us!" "That is as

your mother

wills," said Banda Bela, sitting up. "I have no

mother, though her

picture I wear always upon my breast," she said. "But I will ask old

Jarnik, for all he says the others do," and she sped away to an old

Gypsy,

whose gray hair hung in matted locks upon his shoulders. In a moment

she was

back again, skimming like a bird across the grass. "Searched

through Banda Bela with a keen glance." "I am glad to

eat, but I speak

truth," said Banda Bela calmly. He ate from the

fire-pot hungrily,

dipping the crust she gave him into the stew and scooping up bits of

meat and

beans. "I am filled,"

he said at

length. "I will speak with Jarnik." Marushka danced

across the grass in

front of him like a little will-o'-the-wisp, her fair locks floating in

the

breeze, in the half light her eyes shining like the stars which already

twinkled in the Hungarian sky. The Gypsy dogs

bayed at the moon, hanging like a

crescent over the

crest of the hill and silvering all with its calm radiance. Millions of

fireflies flitted over the plain, and the scent of the ripened grain

was fresh

upon the wind. Banda Bela

sniffed the rich, earthy

smell, the kiss of the wind was kind upon his brow; he was fed and warm. "Life is

sweet," he

murmured. "In the Gypsy camp is brother kindness. If they will have me,

I

will stay." Old Jarnik had

eyes like needles.

They searched through Banda Bela with a keen glance and seemed to

pierce his

heart. "The Gypsy camp

has welcome for

the stranger," he said at length. "Will you stay?" "You ask me

nothing," said

Banda Bela, half surprised, half fearing, yet raising brave eyes to the

stern

old face. "I have nothing

to ask,"

said old Jarnik. "All I wish to know you have told me." "But I have

said nothing,"

said Banda Bela. "Your face to

me lies open as

the summer sky. Its lines I scan. They tell me of hunger, of weariness

and

loneliness, things of the wild. Nothing is there of the city's evil.

You may

stay with us and know hunger no longer. This one has asked for you,"

and the

old man laid his hand tenderly upon little Marushka's head. "You are

hers,

your only care to see that no harm comes to these lint locks. The child

is dear

to me. Will you stay?" "I will stay,"

said Banda

Bela, "and I will care for the child as for my sister. But first I will

speak, since I have nothing to keep locked." "Speak, then,"

said the

old man. Though his face was stern, almost fierce, there was a gentle

dignity

about him and the boy's heart warmed to him. "Of myself I

will tell you all

I know," he said. "I am Banda Bela, son of Šafařik, dead with my

mother. When the camp fell with the great red sickness1

I alone escaped.

Then

was I ten years old. Now I am fourteen. Since then I have wandered,

playing for

a crust, eating seldom, sleeping beneath the stars, my clothes the gift

of

passing kindness. Only my violin I kept safe, for my father had said it

held

always life within its strings. 'Not only food, boy,' he said, 'but joy

and

comfort and thoughts of things which count for more than bread.' So I

lived with

it, my only friend. Now I have two more, you — " he flashed a swift

glance

at the old man, "and this little one. I will serve you well." "You are

welcome," said

old Jarnik, simply. "Now, go to sleep." Little

Marushka, who had been

listening to all that had been said, slipped her hand in his and led

him away

to the boys' tent. She did not walk, but holding one foot in her hand,

she

hopped along like a gay little bird, chattering merrily. "I like you,

Banda Bela, you

shall stay." 1 Smallpox. |