| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Little Journeys To the Homes of Great Scientists Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

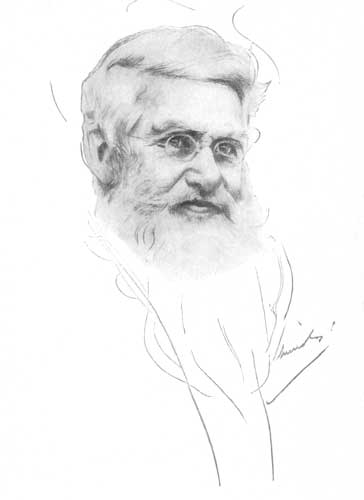

ALFRED R.

WALLACE

"Amok" is an

innovation

which I do not recommend. It consists in letting go when things get too

bad,

and doing damage with tongue, hands and feet. It is the tantrum carried

to its

logical conclusion. I saw one instance where a henpecked husband "ran

amok" and killed or wounded seventeen people before he himself was

killed.

It is the national and therefore the honorable mode of committing

suicide among

the natives of Celebes, and is the fashionable way of escaping from

their

difficulties. A man can not pay, he is taken for a slave, or has

gambled away

his wife or child into slavery, he sees no way of recovering what he

has lost,

and becomes desperate. He will not put up with such cruel wrongs, but

will be

revenged on mankind and die like a hero. He grasps his knife, and the

next

moment draws out the weapon and stabs a man to the heart. He runs on

with

bloody kris in his hand, stabbing every one he meets. "Amok! Amok!"

then resounds through the streets. Spears, krises, knives, guns and

clubs are

brought out against him. He rushes madly forward, kills all he can —

men, women

and children — and dies, overwhelmed by numbers, amid all the

excitement of a

battle. —

Alfred Russel

Wallace, in "The Malay

Archipelago" ALFRED

R.

WALLACE  he question of

how this world and all the things in

it were made, has, so far as we know, always been asked. And volunteers

have at

no time been slow about coming forward and answering. For this service

the

volunteer has usually asked for honors and also exemption from toil

more or

less unpleasant. he question of

how this world and all the things in

it were made, has, so far as we know, always been asked. And volunteers

have at

no time been slow about coming forward and answering. For this service

the

volunteer has usually asked for honors and also exemption from toil

more or

less unpleasant.He has also

demanded the joy of

riding in a coach, being carried in a palanquin, and sitting on a

throne

clothed in purple vestments, trimmed with gold lace or costly furs.

Very often

the volunteer has also insisted on living in a house larger than he

needed,

having more food than his system required, and drinking decoctions that

are

costly, spicy and peculiar. All of which

luxury has been paid

for by the people, who are told that which they wish to hear. The success of

the volunteer lies

in keeping one large ear close to the turf. Religious

teachers have ever

given to their people a cosmogony that was adapted to their

understanding. Who made it?

God made it all. In

how long a time? Six days. And then followed explanations of what God

did each

day. Over against

the volunteers with

a taste for power and a fine corkscrew discrimination, there have been

at rare

intervals men with a desire to know for the sake of knowing. They were

not

content to accept any man's explanation. The only thing that was

satisfying to

them was the consciousness that they were inwardly right. Loyalty to

the God

within was the guiding impulse of their lives. In the past,

such men have been

regarded as eccentric, unreliable and dangerous, and the volunteers

have ever

warned their congregations against them. Indeed, until a

very few years

ago they were not allowed to express themselves openly. Laws have been

passed

to suppress them, and dire penalties have been devised for their

benefit. Laws

against sacrilege, heresy and blasphemy still ornament our

statute-books; but

these invented crimes that were once punishable by death are now

obsolete, or

exist in rudimentary forms only, and manifest themselves in a refusal

to invite

the guilty party to our Four-o'Clock. This hot intent to support and

uphold the

volunteers in their explanations of how the world was made, is a

universal

manifestation of the barbaric state, and is based upon the assumption

that God

is an infinite George the Fourth. Six hundred

years before Christ,

Anaximander, the Greek, taught that animal life was engendered from the

earth

through the influence of moisture and heat, and that life thus

generated

gradually evolved into higher and different forms: all animals once

lived in

the water, but some of them becoming stranded on land put forth organs

of

locomotion and defense, through their supreme resolve to live.

Anaximander also

taught that man was only a highly developed animal, and his source of

life was

the same as that of all other animals; man's present high degree of

development

having gradually come about through growth from very lowly forms. Anaxagoras, the

schoolmaster of

Pericles, also made similar statements, and then we find him boldly

putting

forth the very startling idea that between the highest type of Greek

and the

lowest type of savage there was a greater difference than between the

savage

and the ape. He also taught that the earth was the universal mother of

all

living things, animal and vegetable, and that the fecundation of the

earth took

place from minute, unseen germs that floated in the air. According to

modern science,

Anaxagoras was very close upon the trail of truth. But there were only

a very

few who could follow him, and it took the combined eloquence and tact

of

Pericles to keep his splendid head in the place where Nature put it,

and

Pericles himself was compromised by his leaning toward "Darwinism." Every man who

speaks, expresses

himself for others. We succeed only as our thought is echoed back to us

by

others who think the same. If you like what I say it is only because it

is

already yours. Moreover, thought is a collaboration, and is born of

parents. If

a teacher does not get a sympathetic hearing, one of two things

happens: he

loses the thread of his thought and grows apathetic, or he arouses an

opposition that snuffs out his life. And the dead

they soon grow cold. The recipe for

popularity is to

hunt out a weakness of humanity and then bank on it. No one knows this

better

than your theological volunteer. Aristotle, the father of natural

history, who

early in life had a Pegasus killed under him, taught that the diversity

in

animal life was caused by a diversity of conditions and environment,

and he

declared he could change the nature of animals by changing their

surroundings.

This being true he argued that all animals were once different from

what they

are now, and that if we could live long enough, we would see that

species are

exceedingly variable. To explain to

child-minds that a

Supreme Being made things outright just as they are, is easy; but to

study and

in degree know how things evolved, requires infinite patience and great

labor.

It also means small sympathy from the indifferent whom the earth has

spawned in

swarms, and the hatred of the volunteers who ride in coaches, and tell

the many

what they wish to hear. The volunteers

drove Aristotle

into exile, and from his time they had their way for two thousand

years, when

John Ray, Linnæus and Buffon appeared. In Seventeen

Hundred Fifty-five,

Immanuel Kant, the little man who stayed near home and watched the

stars tumble

into his net, put forth his theory that every animal organism in the

world was

developed from a common original germ. In Seventeen

Hundred Ninety-four,

Erasmus Darwin, the grandfather of Charles Darwin, inspired by Kant and

Goethe,

put forth his book, "Zoonomia," wherein he maintained the gradual

growth and evolution of all organisms from minute, unseen germs. These

views

were put forth more as a poetic hypothesis than as a well-grounded

scientific

fact, so little attention was paid to Erasmus Darwin's books. The

fanciful

accounts of Creation put forth by Moses three thousand years before

were firmly

maintained by the entrenched volunteers and their millions of devotees

and

followers. But Kant,

Goethe, Karl von Baer

and August de Sainte-Hilaire were now planting their outposts

throughout the

civilized world, honeycombing Christendom with doubt. In the year

Eighteen Hundred

Fifty-two, Herbert Spencer had argued in public and in pamphlets that

species

have undergone changes and modifications through change of

surroundings, and

that the account of Noah and his ark, with pairs of everything that

flew, crept

or ran, was fanciful and absurd, so far as we cared to distinguish fact

from

fiction. Early in the

year Eighteen

Hundred Fifty-eight, Charles Darwin received from his friend, Alfred

Russel

Wallace, a paper entitled, "On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart

Indefinitely From the Original Type." At this time Darwin had in the

hands

of the secretary of the Linnæus Society a paper entitled, "On the

Tendency

of Species to Form Varieties, or the Perpetuation of Species and

Varieties by

Means of Natural Selection." The similarity

in title, as well

as the similarity in treatment of the Wallace theme, startled Darwin.

He had

been working on the idea for twenty years, and had an immense mass of

data

bearing on the subject, which he some day intended to issue in book

form. His paper for

the Linnæus Society

simply summed up his convictions. And now here was a man with whom he

had never

discussed this particular subject, writing an almost identical paper

and

sending it to him — of all men! Well did he

pinch his leg, and

call in his wife, asking her if he were alive or dead. Straightway he

went to

see Sir Charles Lyell and Sir Joseph Hooker, both more eminent than he

in the

scientific world, and laid the matter before them. After a long

conference it

was decided that both papers should be read the same evening before the

Linnæus

Society, and this was done on the evening of July First, Eighteen

Hundred

Fifty-eight. Darwin then

decided to publish

his "Origin of Species," which in his preface he modestly calls an

"Abstract." The publication was hastened by the fact that Wallace was

compiling a similar work. After giving Wallace full credit in his most

interesting "Introduction," and reviewing all that others had said in

coming to similar conclusions, Darwin fired his shot heard round the

world. And

no man was more delighted and pleased with the echoing reverberations

than

Alfred Russel Wallace, as he read the book in far-off Australia. The honor of discovering the Law of Evolution, and lifting it out of the hazy realms of hypothesis and poetry into the sunlight of science, will ever be shared between Charles Robert Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, who were indeed brothers in spirit and lovers to the end of their days.  n an

insignificant village of England, now famous

alone because he began from there his explorations of the world, Alfred

Russel

Wallace was born, in the year Eighteen Hundred Twenty-two. He was one

of a

large family of the middle class, where work is as natural as life, and

the

indispensable virtues are followed as a means of self-preservation. It

is most

unfortunate to attain such a degree of success that you think you can

waive the

decalogue and give Nemesis the slip. n an

insignificant village of England, now famous

alone because he began from there his explorations of the world, Alfred

Russel

Wallace was born, in the year Eighteen Hundred Twenty-two. He was one

of a

large family of the middle class, where work is as natural as life, and

the

indispensable virtues are followed as a means of self-preservation. It

is most

unfortunate to attain such a degree of success that you think you can

waive the

decalogue and give Nemesis the slip.About the year

Eighteen Hundred

Forty, the railroad renaissance was on in England, and young Wallace,

alive,

alert, active, did his turn as apprentice to a surveyor. Chance is a

better schoolmaster

than design. All boys have a taste for tent life, and healthy

youngsters not

quite grown, with ostrich digestions, passing through the nomadic

stage, revel

in hardships and count it a joy to sleep on the ground where they can

look up

at the stars, and eat out of a skillet. A little later

we find Alfred

working for his elder brother in an architect's office, gazing

abstractedly out

of the window betimes, and wishing he were a ground-squirrel, fancy

free on the

heath and amid the heather, digging holes, thus avoiding introspection.

"Houses are prisons," he said, and sang softly to himself the song of

the open road. I think I know

exactly how Alfred

Russel Wallace then felt, from the touchstone of my own experience; and

I think

I know how he looked, too, all confirmed by an East Aurora incident. Some years ago,

one fine day in

May, I was helping excavate for the foundation of a new barn. All at

once I

felt that some one was standing behind me looking at me. I turned

around and

there was a tall, lithe, slender youth in a faded college cap, blue

flannel

shirt, ragged trousers and top-boots. My first impression of him was

that he

was a fellow who slept in his clothes, a plain "Weary," but when he

spoke there was a note of self-reliance in his low, well-modulated

voice that

told me he was no mendicant. Voice is the true index of character. "My name is

Wallace, and I

have a note to you from my father," and he began diving into pockets,

and

finally produced a ragged letter that was nearly worn out through long

contact

with a perspiring human form divine — or partially so. I seldom make

haste

about reading letters of introduction, and so I greeted the young man

with a

word of welcome, and gave him a chance to say something for himself. He was English,

that was very

sure — and Oxford English at that. "You see," he began, "I am working

just now over on the Hamburg and Buffalo Electric Line, stringing

wires. I get

three dollars a day because I'm a fairly good climber. I wanted to

learn the

business, so I just hired out as a laborer, and they gave me the

hardest job,

thinking to scare me out, but that was what I wanted," and he smiled

modestly and showed a set of incisors as fine and strong as a dog's

teeth.

"I want to remain with you for a week and pay for my board in work,"

he cautiously continued. "But about your

father, Mr.

Wallace — do I know him?" "I think so; he

has written

you several letters — Alfred Russel Wallace!" You could have

knocked me down

with a lady's-slipper. I opened the letter and unmistakably it was from

the

great scientist, "introducing my baby boy." I never met

Alfred Russel

Wallace, but I know if I should, I would find him very gentle, kindly

and

simple in all his ways — as really great men ever are. He would not

talk to me

in Latin nor throw off technical phrases about great nothings, and I

would feel

just as much at home with him as I did with Ol' John Burroughs the last

time I

saw him, leaning up against a country railroad-station in

shirt-sleeves,

chewing a straw, exchanging salutes with the engineer on a West Shore

jerkwater. "S' long, John!" called the going one as he leaned out of

the cab-window. "S' long, Bill, and good luck to you," was the cheery

answer. But still, all

of us have moments

when we think of the world's most famous ones as being surely eight

feet tall,

and having voices like fog-horns. "I can do most

any kind of

hard work, you know" — I was aroused from my little mental excursion,

and

noticed that my visitor had hair of a light yellow like a Swede from

Hennepin

County, Minnesota, and that his hair was three shades lighter than his

bronzed

face. "I can do any kind of work, you know, and if you will just loan

me

that pick" — and I handed him the pickax. Young Wallace

remained with us

for a week, asking for nothing, doing everything, even to helping the

girls

wash dishes. That he was the son of a great man, no one would have ever

learned

from his own lips. In fact, I am not sure that he was impressed with

his

father's excellence, but I saw there was a tender bond between them,

for he

haunted the post-office, morning, noon and night, looking for a letter

from his

father. When it came he was as happy as a woodchuck. He showed me the

letter:

it was nine finely written pages. But to my

disappointment not a

word about marsupials, siamangs or Syndactylæ: just news about John,

William,

Mary and Benjamin; with references to chickens and cows, and a new

greenhouse,

with a little good advice about keeping right hours and not overeating. The young man

had spent three

years at Oxford, and was an electrical engineer. He was intent on

finding out

just as much about the secrets of American railroad construction as he

possibly

could. As for intellect, I did not discover any vast amount; perhaps,

for that

matter, he didn't either. But we all greatly enjoyed his visit, and

when he

went away I presented him with a clean, secondhand flannel shirt and my

blessing.  rom the

appearance of the young man I imagine that Alfred Russel Wallace

at twenty-one was very much such a man as his son, who did such good

work at

the Roycroft with pick and shovel. Alfred was earnest, intent, strong,

and had

a deal of quiet courage that he was as unconscious of as he was of his

digestion. rom the

appearance of the young man I imagine that Alfred Russel Wallace

at twenty-one was very much such a man as his son, who did such good

work at

the Roycroft with pick and shovel. Alfred was earnest, intent, strong,

and had

a deal of quiet courage that he was as unconscious of as he was of his

digestion.He taught

school, and to interest

his scholars he would take them on botanical excursions. Then he

himself grew

interested, and began to collect plants, bugs, beetles and birds on his

own

account. By Eighteen

Hundred Forty-eight,

the confining walls of the school had become intolerable to Wallace,

and he

started away on a wild-goose chase to Brazil, with a chum by the name

of Henry

Walter Bates, an ardent entomologist. Alfred had no money either, but

Bates had

influence, and he cashed it in by arranging with the Curator of the

British

Museum, that any natural-history specimens of value which they might

gather and

send to him would be paid for. And so something like a hundred pounds

was

collected from several scientific men, and handed over as advance

payment for

the wonderful things that the young men were to send back. They embarked

on a sailing-vessel

that was captained by a kind kinsman of Bates, so the fare was nil, in

consideration of services rendered constructively. Arriving in

Brazil the young men

began their collecting of specimens. They got together a very

creditable

collection of birds' eggs and sent them back by the captain of the ship

they

came out on, this as an earnest of what was to come. Bates and

Wallace were together

for a year. Bates insisted on remaining near the white settlements; but

Wallace

wanted to go where white men had never been. So alone he went into the

forests,

and for two years lived with the natives and dared the dangers of

jungle-fever,

snakes, crocodiles and savages. For a space of ten months he did not

see a

single white person. He collected

nearly ten thousand

specimens of birds, which he skinned and carefully prepared so they

could be

mounted when he returned to England; there was also a nearly complete

Brazilian

herbarium, and a finer collection of birds' eggs than any museum of

England

could boast. This collection

represented over

three years' continuous toil. All the curious things were packed with

great

care and placed on board ship. And so the

young naturalist

sailed away for England, proud and happy, with his great collection of

entomological, botanical and ornithological specimens. But on the way

the ship took

fire, and the collection was either burned or ruined by soaking salt

water. That the crew

and their sole

passenger escaped alive was a wonder. Wallace on reaching England was

in a

sorry plight, being destitute of clothes and funds. And there were

unkind ones who did

not hesitate to hint that he had only been over to Ireland working in a

peat-bog, and that his knowledge of Brazil was gotten out of Humboldt's

books. In one way,

Wallace surely

paralleled Humboldt: both lost a most valuable collection of

natural-history

specimens by shipwreck. Several of the

good men who had

advanced money now asked that it be paid. Wallace set to work writing

out his

recollections, the only asset that he possessed. His book,

"Travel on the

Amazon and Rio Negro," had enough romance in it so that it floated.

Royalties paid over in crisp Bank of England notes made things look

brighter.

Another book was issued, called, "Palm-Trees and Their Uses," and

proved that the author was able to view a subject from every side, and

say all

that was to be said about it. "Wallace on the Palm" is still a

textbook. The debts were

paid, and Alfred

Russel Wallace at thirty was square with the world, the possessor of

much

valuable experience. He also had five hundred pounds in cash, with a

reputation

as a writer and traveler that no longer caused bookworms to sneeze. Having paid off

his obligations,

he felt free again to leave England, a thing he had vowed he would not

do, so

long as his reputation was under a cloud. This time he selected for a

natural-history survey a section of the world really less known than

South

America.  arly in the

year Eighteen Hundred Fifty-four, Alfred Russel Wallace

reached Asia. He had decided that he would make the first and the best

collection of the flora and fauna of the Malay Archipelago that it was

possible

to make. arly in the

year Eighteen Hundred Fifty-four, Alfred Russel Wallace

reached Asia. He had decided that he would make the first and the best

collection of the flora and fauna of the Malay Archipelago that it was

possible

to make.White men had

skirted the coast

of many of the islands, but information as to what there was inland was

mostly

conjecture and guesswork. Just how long

it would take

Wallace to make his Malaysian natural-history survey he did not know,

but in a

letter to Darwin he stated that he expected to be absent from England

at least

two years. He was gone eight years, and during this time, walked,

paddled or

rode horseback fifteen thousand miles, and visited many islands never

before

trod by the foot of a white man. The city of

Singapore served him

as a base or headquarters, because from there he could catch

trading-ships that

plied among the islands of the Archipelago; and to Singapore he could

also ship

and there store his specimens. From Singapore he made sixty separate

voyages of

discovery. In all he sent home over one hundred twenty-five thousand

natural-history specimens, including about ten thousand birds, which,

later on,

were all stuffed and mounted under his skilful direction. On returning to

England, Wallace

took six years in preparation of his book, "The Malay Archipelago," a

most stupendous literary undertaking, which covers the subjects of

botany,

geology, ornithology, entomology, zoology and anthropology, in a way

that

serves as a regular mine of information and suggestion for

natural-history

workers. The book in its

original form, I

believe, sold for ten pounds (fifty dollars), and was issued to

subscribers in

parts. It was bought, not only by students, but by a great number of

general

readers, there being enough adventure mixed up in the science to spice

what

otherwise might be rather dry reading. For instance, there is a chapter

about

killing orang-utans that must have served my old friend, Paul du

Chaillu, as excellent

raw stock in compiling his own recollections. Wallace states

that the only foe

for which the orang really has a hatred is the crocodile. It seems to

share

with man a shuddering fear of snakes, although orangs have no part in

making

Kentucky famous. But the crocodile is his natural and hereditary enemy.

And as

if to get even with this ancient foe, who occasionally snaps off a

young orang

in his prime, the orangs will often locate a big crocodile, and jumping

on his

back beat him with clubs; and when he opens his gigantic mouth, the

female

orangs will fill the cavity with sticks and stones, and keep up the

fight until

the crocodile succumbs and quits this vale of crocodile tears. The orang is

distinct and

different from the chimpanzee and gorilla, which are found only in

Western

Africa. In Borneo, the

"man-ape" is quite numerous. This is the animal that has given rise

to all those tales about "the wild man of Borneo," which that good

man, P. T. Barnum, kept alive by exhibiting a fine specimen. Barnum's

original

"wild man" lived at Waltham, Massachusetts, and belonged to the

Baptist Church. He recently died worth a hundred thousand dollars,

which money

he left to found a school for young ladies. The orang, or

mias, hides in the

swampy jungles, and very rarely comes to the ground. The natives regard

them as

a sort of sacred object, and have a great horror of killing them.

Indeed, a

person who kills a man-ape, they regard as a murderer; and so when

Wallace

announced to his attendants that he wanted to secure several specimens

of these

"wild men of the woods," they cried, "Alas! he is making a

collection: it will be our turn next!" And they fled in terror. Wallace then

hired another set of

servants and resolved to make no confidants, but just go ahead and find

his

game. He had hunted

for weeks through

forest and jungle, but never a glimpse or sight of the man-ape! He had

almost

given up the search, and concluded with several English scientists that

this

orang-utan was a part of that great fabric of pseudo-science invented

by

imaginative sailormen, who took most of their inland little journeys

around the

capstan. And so musing, seated in the doorway of his bamboo house, he

looked

out upon the forest, and there only a few yards away, swinging from

tree to

tree, was a man-ape. It seemed to him to be about five times as large

as a man. He seized his

gun and approached;

the beast stopped, glared, and railed at him in a voice of wrath. It

broke off

branches and threw sticks at him. Wallace thought

of the offer made

him by the South Kensington Museum: "One hundred pounds in gold for an

adult male, skin and skeleton to be properly preserved and mounted;

seventy-five pounds for a female." The huge animal

showed its teeth,

cast one glance of scornful contempt on the puny explorer, and started

on,

swinging thirty feet at a stretch and catching hold of the limbs with

its two

pairs of hands. Wallace grasped

his gun and

followed, lured by the demoniac shape. A little of the superstition of

the

natives had gotten into his veins: he dare not kill the thing unless it

came

toward him, and he had to shoot it in self-defense. It traveled in

the trees about as

fast as he could on the ground. Occasionally it would stop and chatter

at him,

throwing sticks in a most human way, as if to order him back. Finally, the

instincts of the

naturalist got the better of the man, and he shot the animal. It came

tumbling

to the ground with a terrific crash, grasping at the vines and leaves

as it

fell. It was quite

dead, but Wallace

approached it with great caution. It proved to be a female, of moderate

size,

in height about three and a half feet, six feet across from finger to

finger.

Needless to say that Wallace had to do the skinning and the mounting of

the

skeleton alone. His servants had chills of fear if asked to approach

it. The

skeleton of this particular orang can now be seen in the Derby Museum. In a few hours

after killing his

first orang, Wallace heard a peculiar crying in the forest, and on

search found

a young one, evidently the baby of the one he had killed. The baby did

not show

any fear at all, evidently thinking it was with one of its kind, for it

clung

to him piteously, with an almost human tenderness. Says Wallace: "When handled

or nursed it

was very quiet and contented, but when laid down by itself would

invariably

cry; and for the first few nights was very restless and noisy. I soon

found it

necessary to wash the little mias as well. After I had done so a few

times it

came to like the operation, and after rolling in the mud would begin

crying,

and continue until I took it out and carried it to the spout, when it

immediately became quiet, although it would wince a little at the first

rush of

the cold water, and make ridiculously wry faces while the stream was

running

over its head. It enjoyed the wiping and rubbing dry amazingly, and

when I

brushed its hair seemed to be perfectly happy, lying quite still with

its arms

and legs stretched out. It was a never-failing amusement to observe the

curious

changes of countenance by which it would express its approval or

dislike of

what was given to it. The poor little thing would lick its lips, draw

in its

cheeks, and turn up its eyes with an expression of the most supreme

satisfaction, when it had a mouthful particularly to its taste. On the

other hand,

when its food was not sufficiently sweet or palatable, it would turn

the

mouthful about with its tongue for a moment, as if trying to extract

what

flavor there was, and then push it all out between its lips. If the

same food

was continued, it would proceed to scream and kick about violently,

exactly

like a baby in a passion. "When I had had

it about a

month it began to exhibit some signs of learning to run alone. When

laid upon

the floor it would push itself along by its legs, or roll itself over,

and thus

make an unwieldy progression. When lying in the box it would lift

itself up to

the edge in an almost erect position, and once or twice succeeded in

tumbling

out. When left dirty or hungry, or otherwise neglected, it would scream

violently till attended to, varied by a kind of coughing noise, very

similar to

that which is made by the adult animal. "If no one was

in the house,

or its cries were not attended to, it would be quiet after a little

while; but

the moment it heard a footstep would begin again, harder than ever. It

was very

human."  he most lasting

result of the wanderings of Alfred Russel Wallace

consists in his having established what is known to us as "The Wallace

Line." This line is a boundary that divides in a geographical way that

portion of Malaysia which belongs to the continent of Asia from that

which

belongs to the continent of Australia. he most lasting

result of the wanderings of Alfred Russel Wallace

consists in his having established what is known to us as "The Wallace

Line." This line is a boundary that divides in a geographical way that

portion of Malaysia which belongs to the continent of Asia from that

which

belongs to the continent of Australia.The Wallace

Line covers a

distance of more than four thousand miles, and in this expanse there

are three

islands in which Great Britain could be set down without anywhere

touching the

sea. Even yet the

knowledge of the

average American or European is very hazy about the size and extent of

the

Malay Archipelago, although through our misunderstanding with Spain,

which

loaded us up with possessions we have no use for, we have recently

gotten the

geography down and dusted it off a bit. There is a book

by Mrs. Rose

Innes, wife of an English official in the Far East, who, among other

entertaining things, tells of a head-hunter chief who taught her to

speak Malay,

and she, wishing to reciprocate, offered to teach him English; but the

great

man begged to be excused, saying, "Malay is spoken everywhere you go,

east, west, north or south, but in all the world there are only twelve

people

who speak English," and he proceeded to name them. Our assumptions

are not quite so

broad as this, but few of us realize that the Protestant Christian

Religion

stands fifth in the number of communicants, as compared with the other

great

religions, and that against our hundred millions of people in America,

the

Malay Archipelago has over two hundred millions. Wallace found

marked geological,

botanical and zoological differences to denote his line. And from these

things

he proved that there had been great changes, through subsidence and

elevation

of the land. At no very remote geologic period, Asia extended clear to

Borneo,

and also included the Philippine Islands. This is shown by the fact

that animal

and vegetable life in all of these islands is almost identical with

life on the

mainland: the same trees, the same flowers, the same birds, the same

animals. As you go

westward, however, you

come to islands which have a very different flora and fauna, totally

unlike

that found in Asia, but very similar to that found in Australia. Australia, be

it known, is

totally different in all its animal and vegetable phenomena from Asia. In Australia,

until the white man

very recently carried them across, there were no monkeys, apes, cats,

bears,

tigers, wolves, elephants, horses, squirrels or rabbits. Instead there

were

found animals that are found nowhere else, and which seem to belong to

a

different and so-called extinct geologic age, such as the kangaroo,

wombats,

the platypus — which the sailors used to tell us was neither bird not

beast,

and yet was both. In birds, Australia has also very strange specimens,

such as

the ostrich which can not fly, but can outrun a horse and kills its

prey by

kicking forward like a man. Australia also has immense mound-making

turkeys,

honeysuckers and cockatoos, but no woodpeckers, quail or pheasants. Wallace was the

first to discover

that there are various islands, some of them several hundred miles from

Australia, where the animal life is identical with that of Australia.

And then

there are islands, only a comparatively few miles away, which have all

the

varieties of birds and beasts found in Asia. But this line

that once separated

continents is in places but fifteen miles wide, and is always marked by

a

deep-water channel, but the seas that separate Borneo and Sumatra from

Asia,

although wide, are so shallow that ships can find anchorage anywhere. The Wallace

Line, proving the

subsidence of the sea and upheaval of the land, has never been

seriously

disputed, and is to many students the one great discovery by which

Wallace will

be remembered. Wallace's book

on "The

Geographical Distribution of Animals" sets forth in a most interesting

manner, the details of how he came to discover the Line. It was in

Eighteen Hundred

Fifty-five that Wallace, alone in the wilds of the Malay Archipelago,

became

convinced of the scientific truth that species were an evolution from a

common

source, and he began making notes of his observations along this

particular

line of thought. Some months afterward he wrote out his belief in the

form of

an essay, but then he had no definite intention of what he would do

with the

paper, beyond keeping it for future reference when he returned to

England. In

the Fall of Eighteen Hundred Fifty-seven, however, he decided to send

it to

Darwin to be read before some scientific society, if Darwin considered

it

worthy. And this paper was read on the evening of July First, before

the

Linnæus Society, with one by Darwin on the same subject, written before

Wallace's paper arrived, wherein the identical views are set forth.

Darwin and

Wallace expressed what many other investigators had guessed or but

dimly

perceived.  f the six

immortal modern scientists, three began life working as

surveyors and civil engineers — Wallace, Tyndall, Spencer. From the

number of

eminent men, not forgetting Henry Thoreau, Leonardo da Vinci, Lincoln,

Ulysses

S. Grant, Washington — aye! nor old John Brown, who carried a Gunter's

chain

and manipulated the transit — we come to the conclusion that there must

be

something in the business of surveying that conduces to clear thinking

and

strong, independent action. f the six

immortal modern scientists, three began life working as

surveyors and civil engineers — Wallace, Tyndall, Spencer. From the

number of

eminent men, not forgetting Henry Thoreau, Leonardo da Vinci, Lincoln,

Ulysses

S. Grant, Washington — aye! nor old John Brown, who carried a Gunter's

chain

and manipulated the transit — we come to the conclusion that there must

be

something in the business of surveying that conduces to clear thinking

and

strong, independent action.If I had a boy

who by nature and

habit was given to futilities, I would apprentice him to a civil

engineer. When two gangs

of men begin a

tunnel, working toward each other from different sides of a mountain,

dreams,

poetry, hypothesis and guesswork had better be omitted from the

equation. Here

is a case where metaphysics has no bearing. It is a condition that

confronts

them, not a theory. Theological

explanations are

assumptions built upon hypotheses, and your theologian always insists

that you

shall be dead before you can know. If a bridge

breaks down or a

fireproof building burns to ashes, no explanation on the part of the

architect

can explain away the miscalculation; but your theologian always evolves

his own

fog, into which he can withdraw at will, thus making escape easy.

Darwin,

Huxley, Spencer, Tyndall and Wallace all had the mathematical mind.

Nothing but

the truth would satisfy them. In school, you remember how we sometimes

used to

work on a mathematical problem for hours or days. Many would give it

up. A few

of the class would take the answer from the book, and in an extremity

force the

figures to give the proper result. Such students, it is needless to

say, never

gained the respect of either class or teacher — or themselves. They had

the

true theological instinct. But a few kept on until the problem was

solved, or

the fallacy of it had been discovered. In life's school such were the

men just

named, and the distinguishing feature of their lives was that they were

students and learners to the last. Of this group

of scientific

workers, Alfred Russel Wallace alone survives, aged eighty-nine at this

writing, still studying, earnestly intent upon one of Nature's secrets

that

four of his great colleagues years ago labeled "Unknown," and the

other two marked "Unknowable." To some it is

an anomaly and

contradiction that a lover of science, exact, cautious, intent on

certitude,

should accept a belief in personal immortality. Still, to others this

is

regarded as positive proof of his superior insight. All thinking

men agree that we

are surrounded by phenomena that to a great extent are unanalyzed; but

Herbert

Spencer, for one, thought it a lapse in judgment to attribute to spirit

intervention, mysteries which could not be accounted for on any other

grounds.

It was equal to that sin against science which Darwin committed, and

which he

atoned for in contrite public confession, when he said: "It surely must

be

this, otherwise what is it? Hence we assume," and so on. Some recent

writers have sought to demolish Wallace's argument concerning Spiritism

by

saying he is an old man and in his dotage. Wallace once wrote a booklet

entitled, "Vaccination a Fallacy," which created a big dust in

Doctors' Row, and was cited as corroborative proof, along with his

faith in

Spiritism, that the man was mentally incompetent. But this is a

deal worse excuse

for argument than anything Wallace ever put forth. The real fact is

that

Wallace issued a book on Spiritism in Eighteen Hundred Seventy-four,

and in

Eighteen Hundred Ninety-six reissued it with numerous amendments,

confirming

his first conclusions. So he has held his peculiar views on immortality

for

over thirty years, and moreover his mental vigor is still unimpaired. Whether the

proof he has received

as to the existence of disembodied spirits is sufficient for others is

very

uncertain; but if it suffices for himself, it is not for us to quibble.

Wallace

agrees to allow us to have our opinions if we will let him have his. His views are

in no sense those

of Christianity; rather, they might be called those of Theosophy, as

the

personal God and the dogma of salvation and atonement are entirely

omitted. The Doctrine of

Evolution he

carries into the realm of spirit. His belief is that souls reincarnate

themselves many times for the ultimate object of experience, growth and

development. He holds that this life is the gateway to another, but

that we

should live each day as though it were our last. To this effect

we find, in a

recent article, Wallace quotes a little story from Tolstoy: A priest,

seeing a

peasant in a field plowing, approached him and asked, "How would you

spend

the rest of this day if you knew you were to die tonight?" The priest

expected the man, who

was a bit irregular in his churchgoing, to say, "I would spend my last

hours in confession and prayer." But the peasant replied, "How would

I spend the rest of the day if I were to die tonight? — why, I'd plow!" Hence, Wallace

holds that it is

better to plow than to pray, and that in fact, when rightly understood,

good

plowing is prayer. All useful effort is sacred, and nothing else is or ever can be. Wallace believes that the only fit preparation for the future lies in improving the present. Please pass the dotage! |