| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2013 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

III LANDSCAPE GARDENS HAVING made some attempt to elucidate the mysterious and wonderful construction of Japanese gardens, I feel the reader will expect to learn something of their effect as a whole when completed. Unfortunately many of the finest specimens of landscape gardens, the old Daimyos' gardens in Tokyo, have been swept away to make room for foreign houses, factories, and breweries, and no trace of them remains; old drawings or photographs alone tell of their departed glories. Probably the largest of these gardens which still remains entire is the Koraku-en, or Arsenal Garden, as it is more commonly called. It is now empty and deserted, and seems only filled with sadness, its groves recalling days gone by, when succeeding Daimyos entertained their friends in regal pomp, and the sound of revelry broke the silence of the woods; to-day only the incessant sound of metal hammering metal breaks the silence of the glades, and the sound of explosions from the Arsenal near by might well rouse the dead. The garden covers a large extent of ground, and is an example of a scheme in which many separate scenes were skilfully worked together to form a perfect whole. Its fame dates from early in the seventeenth century, when the Daimyo of Mito, who was a great patron of landscape gardening, laid out the grounds. The fact that they are remarkable for many Chinese characteristics is not surprising, when we learn that the Shogun Iyemitsu took an interest in the work, and lent the aid of a great Chinese artist called Shunseu, who completed the scheme. A semicircular stone bridge of Chinese design, called a Full-moon Bridge, spans a stretch of water in which, in the scorching heat of August mornings, the great buds of white lotus flowers will crack and slowly open, their giant leaves almost hiding the bridge; this important feature of the garden is called Seiko Kutsumi, after a famous lotus lake in China. The island in the lake is the Elysian Isle of Chinese fame, and formerly was connected with the shore by a long wooden bridge, which has long since disappeared; but the path wanders on, past the rocky shore, skirting the headland and high wooded promontory, through the dense gloom of a forest, and by the time I had made a complete tour of this garden I felt as though I had paid a flying visit to half Japan.

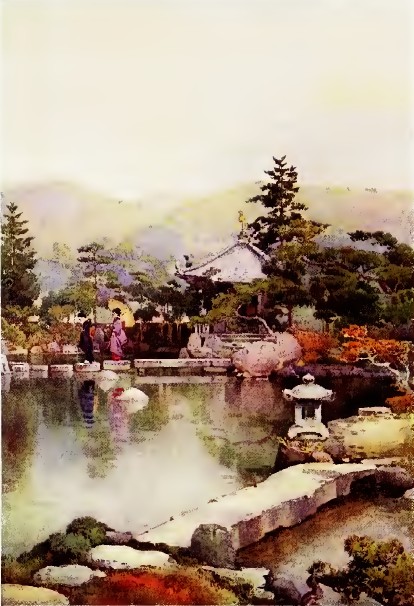

An Old Garden There was an avenue of cherry-trees to recall the avenues of Koganei; the river Tatsuda in miniature, its banks clothed with maples and other reddening trees, to give colour to the garden in autumn, when the setting sun will seem to light the torch and set all the trees ablaze; there also is the Oi-gawa or Rapid River with its wide pebble-strewn bed, down which a rapid-flowing stream is brought; then we are transported to scenes in China; and beyond, again, the wanderer is reminded of the scenery of Yatsuhashi, where one of the eight bridges crosses in zigzag fashion a marshy swamp which in the month of June is a mass of irises, great gorgeous blossoms of every conceivable shade of lilac and purple, completely hiding their foliage; then this little valley becomes a stream of colour and recalls the more extensive glories of Hori-kiri. Perhaps most ingenious of all is that part of the garden where the cone of Fuji-yams appears, snow-capped in May, as it is densely planted with white azaleas. Many other scenes there were tiny shrines built in imitation of great temples, cascades and waterfalls named after other celebrated falls, rare rocks, moss-grown lanterns, bridges of all designs; in fact, the garden seemed a perfect treasure-house, and I felt glad that this one garden has escaped the hand of the destroyer and is left entire, a masterpiece of conception and execution. Of another Tokyo garden which unfortunately has not been left untouched, as it is shorn of half its former glories, a glaring red-brick brewery covering half the area of the beautiful grounds formerly known as Satake-no-niwa only a portion remains, though a very lovely portion, and as it seems complete in itself it is still worth a visit. Unlike the Koraku-en, the Satake Garden was a rather artificial example of hill gardening, more open, with no dense groves, but essentially a hill and water garden. The large lake remains, and, like most of the gardens in the Honjo district of Tokyo, its waters are salt and tidal, being connected with the neighbouring river Sumida. Thus at high and low tide the shores of the lake present a very different aspect; pebbly bays can only be crossed by stepping-stones at high tide, and even some of the stone lanterns by the water's edge have their standards half submerged. The hills are closely planted with evergreen bushes and shrubs, and most of the year the garden is all grey and green; the island is reached by a grey stone bridge formed of two slabs of granite of giant proportions, the grey lanterns stand among shrubs, cut into rounded form, and the mossy rocks and boulders have still more neutral tones; so it is only in spring when Nature asserts herself, and no gardener can prevent the young leaves of the maples being a variety of vivid colouring, and the grey rounded azalea bushes become perfect balls of scarlet, rosy-pink and white blossoms, that the garden has any colour in it. But to the mind of the Japanese all sense of repose and quiet charm would be gone if the eye were always worried by a distracting mass of colour; so even if flowers were grown in these more extensive gardens they had a special part of the grounds set apart for their culture. In one corner of the lake a piece of swampy ground was thickly planted with irises and water-plants, and a wistaria trellis overhung the lake, otherwise no flowers entered into the scheme; but it was a perfect specimen of the typical Japanese arrangement of garden hills planted with rounded bushes and adorned with lanterns.  Satake Garden, Tokyo A magnificent example of a modern landscape garden is that belonging to Baron Iwasaki, made some forty years ago. The venerable pine-trees supported by stout props overhanging the lake are suggestive of countless ages; but in this garden old trees of gnarled and twisted growth, rare rocks, and immense boulders were collected from all parts of the empire, regardless of expense, and brought together to ensure the success of the scheme. The grounds cover many acres, the one blot in the landscape being the large red-brick foreign house; but luckily the most lovely part of the garden is laid out in front of the perfect specimen of a Japanese gentleman's house, where the verandah of the cool matted rooms looks over a scene of indescribable beauty. The large lake is cleverly divided, and the portion of the garden in front of the foreign house is left behind; groves of evergreen trees screen the house the one jarring note; and here the lake becomes the lagoon of Matsu-shima, tiny pine-clad islets rise from the water, and in the distance rises the cone of Fuji from an undulating plain of close-mown turf and groups of dwarfed pines. Here again flowers have no official existence; azaleas there are in profusion, but they are only introduced as shrubs; so the garden is not a flower garden, but a true landscape garden the reproduction in miniature of natural scenery. The lanterns and bridges near the foreign house are of immense size, carrying out the law of proportion; the rocks and boulders are large to correspond, and the whole effect is one of great breadth; only near the tea-house and the main Japanese house does the garden become more finished in style and on a smaller scale. The balcony overhangs the rocky edge of the tidal lake; each rock has its history and its especial place; but the laws which have governed the making of such a garden are laws drawn up by great artists, there is no false note, even the grouping of the reeds and irises by the water's edge has been planned by a master hand, so the picture remains graven on one's memory as that of an ideal pleasaunce for leisure and repose. In Kyoto there still remain the gardens of the Gold and Silver Pavilions gardens of much older date, the splendour of their pavilions dimmed by age, more especially in the case of Kinkakuji, the Golden Pavilion. Mr. Conder says, "Long neglect has converted what was once an elaborate artificial landscape into a wild natural scene of great beauty." The little pine-clad islets remain, but they are now island wildernesses; the trees have partially resumed their normal shapes; great leaning pines overhang the shores of the Mirror Ocean, representing the Sea of Japan, and its three islands suggesting the Empire of the Mikado. It was in the fourteenth century that this quiet spot became the so-called retreat of the scheming Yoshimitsu, who, pretending to have resigned the Shogunate in favour of his son, here lived in the garb of a monk, but in reality directing the affairs of State. The two-storied Pavilion itself, seen reflected in the Mirror Ocean, is possibly more picturesque in decay than it was in the days of its splendour; the gilding from which it takes its name has been partially restored; it is backed by the wooded hill fancifully called the Silken Canopy or Silk Hat Mountain, from the fact that the ex-Mikado Uda ordered it to be covered with white silk on a scorching summer's day, in order that his eyes might enjoy the sensation of gazing on a cool, snow-covered scene. To this day the garden of Kinkakuji under a light canopy of snow is one of the favourite sights of the people of Kyoto. In days gone by there were smaller arbours in which the Shogun, wearied with his walk among the groves of the Silk Hat Mountain, would rest, and compare the scene which the garden was intended to represent, to the real Sea of Japan, whence the name of one of the arbours, The House of the Sound of the Seashore.

A Tokyo Garden To the north-east of Kyoto, nestling among the woods that clothe the lower hills of Hiei-san, lie the grounds of Ginkakuji or the Silver Pavilion. In imitation of his predecessor Yoshimitsu, the Shogun Yoshimasa after his abdication retired from the affairs of the world, built himself a country house with grounds of vast extent, even with despotic impatience sweeping away a temple because it interfered with his plans, though we are told he was filled with remorse, and afterwards restored it at great expense. The two-storied Pavilion was partly copied from its rival, the Golden Pavilion, though it never seems to have attained to the same splendour; but here the ex-Shogun and his boon companions, the philosopher Soami and Shuko the Nara priest, held their aesthetic revels. They may be said to have laid down the laws which raised the tea-ceremonial to the rank of a fine art. Mr. Farrar, in writing of it, says: It

has its prescribed ritual of appalling rigidity, this tea ceremony,

invented and elaborated by a pious monk to distract a young and giddy

Shogun from his debaucheries. It was taken up as a political weapon

by the House of Tokugawa, and crystallised into its present

adamantine form, becoming a social engine of the most powerful nature

in its power of bringing all the nobles together. Here, then, is one

of its temples where the rites were celebrated in their due

ordinance, with their prescribed compliments, obeisances, and

admiring exclamations over the prescribed flower, arranged in the

prescribed spot, and indicated by the host in the prescribed words,

to be followed by the invariable litany of conversation and courtesy

over the cup of tea to be made, handed, accepted, and drunk all with

remarks and gestures and smiles of ancestral rubric. Outside any tea-house built in accordance with these prescribed regulations one sees "a row of stepping-stones, finishing beneath a little il-de-buf in the wall above, by which the visitors had to enter, ignoring the thoroughly practical door. They approached, making the due bows upon each stone, and at last their host was to fish them in through the window." Another ceremony inaugurated within these precincts was the ceremonial of "incense sniffing," to our minds merely an innocent, childish game, the winner being the person possessing the keenest sense of smell, as the pastime consisted of five or more different kinds of incense being burnt, sniffed, given poetical names, then mixed up and sniffed again, and the man who guesses best the names of the various kinds, is the winner. The boxes which contained the incense, the burners in which it was burnt, were all works of art, and the same grave etiquette which governed the tea-ceremonial governed these incense-sniffing parties, in which poets, writers, priests, philosophers, Daimyos, Shoguns, the greatest and most learned in the land, took part. We can only gaze with wonder and perplexity not hoping to understand at a "nation's intellect going off on such devious tracks as this incense-sniffing and the still more intricate tea-ceremonies, and on bouquets arranged philosophically, and gardens representing the cardinal virtues. Such strict rules, such grave faces, such endless terminologies, so much ado about nothing!" (Professor Chamberlain's Things Japanese.) To return to the garden proper, laid out with great elaboration by Soami. Although it is now much neglected, the trees are not kept trimmed according to the rigid laws, their stems are lichen-clad, and Nature has tried to reassert herself over art, yet the beauty of the spot is great. The lake, of ingenious form, backed on the north side by the thickly pine-clad hills and to the west by the regulation grove of maples, is an admirable example of the arrangement of garden stones, its shores being rich in rare and precious rocks, each with its characteristic name. One of the principal stones lying in the lake is the stone of Ecstatic Contemplation; the little bridge which divides the lake is the Bridge of the Pillar of the Immortal; the water of the cascade which fills the lake, being of exceptional purity, is called the Moon-washing Fountain. In the foreground of many of these older gardens was an open space covered with white sand, carefully raked into ornamental patterns, and here is a large mound of the sand suggestive of a mammoth sugar-loaf with a flattened top, called the Silver Sand Platform, the smaller one of the same shape being the Mound facing the Moon; on these sat Yoshimasa and his favourites, indulging in another favourite pastime of moon-gazing, to our prosaic minds merely another elaborately conceived method of killing time. I know no garden in Japan which seemed to take one back so far into the world of the Old Japan as this little garden of Ginkakuji, and no more peaceful spot to sit and enjoy the reddening maple leaves on a bright evening in late autumn, when there is a touch of sadness in the air, in keeping with the departed glories of the Pavilion and the fast-fading beauties of the trees. Many of the smaller and most interesting gardens in Japan are those attached to tea-houses or small suburban houses, showing, as they do, the ingenuity and resource of the landscape gardener in making a perfect garden of any size, from ten acres to half an acre, or only a few square yards. Among tea-house gardens, that attached to the Raku-raku-tei at Hikone can hardly be counted, as it was formerly the garden of a great Daimyo and is one of the finest gardens in the country. The numerous little summer-houses built out on piles in the lake have been erected for the entertainment of the guests of the tea-house, a gathering place for the most elite, but otherwise the garden remains unchanged; the paths which wind round the lake, across the bridges, past the Stone of Worship, from where the beauties of the garden may be enjoyed to best advantage, are the same paths which the feet of successive Daimyos trod in the feudal days of old. It is rather to the Hira-niwa, or Flat Gardens, that I allude, made in the small enclosures at the back of private houses or tea-houses in towns, or even in the actual courts, no space being apparently too small for the construction of one of these little fresh-looking and artistic gardens. How superior to the dusty, neglected back garden or court of a European house, too often only a piece of waste ground where the rubbish of the house accumulates, the space being condemned as too small for a garden. I can recall visions of many a tiny court no more than twenty feet square, within whose limits were compressed a liliputian pond, fed with clear water by the overflow of the water-basin; a dwarf pine, the soul of every Japanese garden, which in conjunction with a few small evergreen shrubs sheltered a moss-grown lantern. Some small rocks and a few foliage or water plants in a tuft by the water's edge, were the sole materials used for the making of this court-garden. Stepping-stones, let into the beaten earth, led from the step of the verandah to the edge of the pond, ending in one stone larger than the rest, suggesting the Stone of Worship, or the Stone of Amusement, in case there should be any goldfish in the pond. As these little courts are kept profusely watered, being sprinkled out of a wooden ladle several times a day in the hottest days of summer, the effect is always damp and cool, the mossy stones are always fresh and green, however fierce the heat may be. The variety in the actual form of these gardens seemed infinite; in some the pond was omitted, and the suggestion of water and dampness came from the rustic garden well or the ornamental water-basin, behind which always stands a portion of screen-fencing of elaborate design. When the area is not quite so limited, bridges will be introduced to cross the pond, possibly consisting only of a single stone slab supported on a natural piece of rock, or a granite bridge slightly curved in form, or perhaps only the suggestion of a bridge, formed of a branch of juniper or some flat close-growing evergreen trained in a curve across the water. According to the size of the ground, so these gardens will increase in elaboration of their design, and many an enclosure at the back of a merchant's house in Kyoto or Osaka has been transformed into a perfect specimen of Hira-niwa. One I recall which always gave me as much pleasure as the most extensive landscape garden in the country. The lake was of the prescribed form known as the Running Water shape, fed by a fast-flowing stream which came in at the far end of the garden over the regulation Cascade Stones; a garden arbour of elaborate form overlooked the lake, in which stood the "Elysian Isle" with its pine-tree growing out of the rock, and a few azalea bushes filling the interstices of the stone, forming a most attractive feature of the garden; banks there were planted with more azaleas; pines, kept dwarfed to about two feet in height, grew out of cushions of thick moss; bridges crossed and re-crossed the stream; stepping-stones, discs, and label stones guided our feet as we wandered about at leisure. There were the two garden entrances, and even the back entrance, or Sweeping Opening, was a thing of beauty. Every detail of this garden had been first carefully thought out, and then as carefully carried into execution.

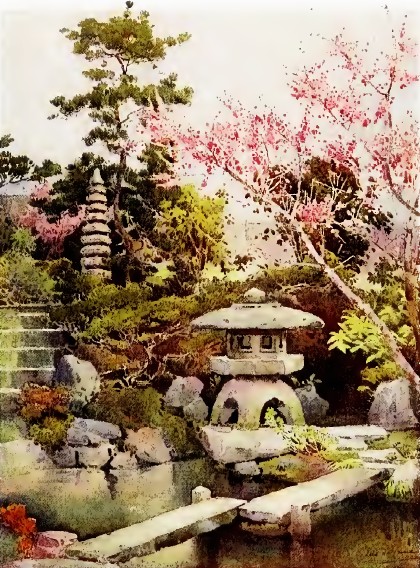

A Landscape Garden The landscape gardener in Japan is no gardener in the sense that we regard a gardener in the West a cultivator of flowers: he is a garden artist; he leaves none of his effects to chance; so carefully are his plans made that before the first sod of the new garden has been turned, he knows exactly how the garden will look when completed. He will see in his mind's eye the appointed place for every tree, every stone, which is to be used in its composition. I could not help thinking that if more thought were given to the planning of our English gardens there might be something more complete and satisfying to the eye than the meaningless gardens often laid out by the owner of the house, who by the wildest stretch of imagination could not be called a garden artist which too often surround our English homes. Our gardens are made beautiful in summer by the wealth and profusion of their flowers; but when the winter comes and the beds are shorn of their summer glories, the deficiencies of the plan of the garden are laid bare, and might well give us food for thought through the long winter months. |