| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

XXI

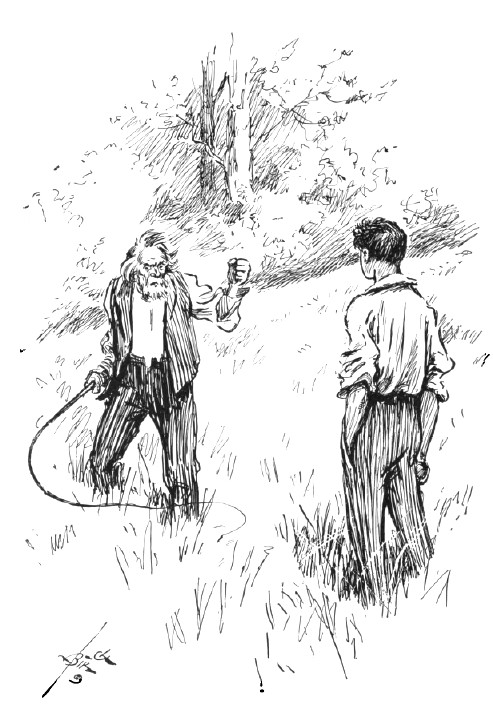

THE NEIGHBORHOOD NUISANCE THE neighborhood to which I had moved was regarded by those long resident there as one of the finest and most exclusive in the town. The houses were large and well-kept, the lawns green and trim, and the grounds spacious. It was peculiar in having a number of very lofty and fine pine trees growing amid a profusion of elms and oaks. This distinction added much to the pride and exclusiveness of the residents, and in fact set them apart from other men. In short, the neighborhood fairly exhaled pride and satisfaction, and not without reason; and when we entered its charmed and sacred precincts we felt that we were personć non grata. Such things do not bother me very much, but they affect my wife's peace of mind exceedingly, who, poor woman, has found in me a very serious handicap to her social aspirations. It is difficult for conservative and semi-bucolic village society to clasp to its bosom with any open show of affection one who views village neighbors and village life with amusement. Indeed, in the Greek Quarter of the town in which I had spent five happy and amusing years, I was viewed with the utmost suspicion and my wife pitied, because I had committed the entire neighborhood to print, and had made them severally, and, according to the sale of the book, more or less, immortal. And when we moved from that delightful neighborhood we realized that our departure did not affect the price of real estate to any marked degree. In the next neighborhood where we spent a year, we were not over-popular, because we had long outgrown the cabinet-organ and plush-album stage, and did not regard the cuspidore as a household necessity; nor did I aspire to occupy any of the chairs in the many lodges and secret orders with which the face of our beloved village was thickly speckled. And so, when I moved to the farm, I made up my mind to view men and things with a more serious eye, and in short, to be good and live happily ever afterwards. It was hard, however, to break a habit of years. When one has spent the greater part of one's life in seeing the amusing side of men and things, it is hard, desperately hard, to close one's eyes and thoughts to the humorous sights and ideas that association with one's neighbors brings. And the sight of some of my dignified neighbors pokering their unbending way townwards, brought forcibly to my mind the necessity of in some way ingratiating myself with them if I was to be a valued member of the colony and in good standing. With Daniel the way was open. One view of Daniel's three hundred pounds of good nature was enough to assure any man of a welcome, provided he desired and deserved it. But the Professors and the wealthy magnate, the retired New Yorker, the two old ladies of a by-gone generation, who still wore lace mitts and side-curls and rather voluminous black silk skirts, and who occasionally screened their fine old faces with small silk parasols with jointed handles, and the two old gentlemen who took pains to inform me that they used to trade with my grandfather, and what a fine courteous old gentleman he was, and how things had changed since his time, — they were more difficult. And when I reflected that the last owner of the farm was a treasurer of the Academy, and a trustee thereof, for many many years superintendent of a Sunday School, and a man of weight (not physical, however, for he was of inconsiderable size) and influence in the community, I realized that comparisons would be, and in all probability had been, drawn, —comparisons which, like comparisons in general, were odious. It was really quite a serious question. Whether to go on as I had been doing, and look upon my small corner of the world with a humorous disregard, and attend strictly to my own affairs, the duties of my profession from nine to five, and the cultivation of my soil from five to dark, with the interval of the dinner, or to fairly lay myself out to the entertainment of the neighborhood. I really wished to be liked by my new neighbors because I wanted to live in the neighborhood and make myself one of them. I wanted to be able to walk in upon them without formality, to have them drop in socially to a pipe or to lunch; to discuss matters of common interest, — the growth of the crops, the relative butter qualities of the Jerseys, the Ayrshires, the Guernseys, and the Belted Dutch; the comparative egg-productiveness of the Minorcas, the Buff Wyandottes, and the Orpingtons; whether Aldrich was a real poet or a graceful dilettante; how many rounds it took Jeffries to put Corbett down and out; who was the first American educator, Old Man Anson or Doctor Eliot, and other matters of bucolic interest. The best method of attaining this desired end was the thing that occupied me day and night. We could not invite them to our house until they had called, and we were not the people to slight or neglect our old friends for the purpose of obtaining favor with new ones. I tried various expedients. I purposely let out my hens one day in May, and true to the fiendish nature of these unaccountable bipeds, they instantly departed to a neighbor's garden and excavated huge holes therein. This was my cue to rush in with a whip, drive them back to my own premises, and then with my hired man to work a couple of hours in putting the garden into very much better condition than it ever was in before, to the great approval of the neighbor, who might otherwise have remained in a state of dignified conservatism forever. Another neighbor's cow got loose, and in one night ate about half of my young sweet corn, where the young plants were six inches high. I carefully piloted the animal home and assured the apologetic owner that the damage was not worth considering, that my horse or cow was liable to get loose any day and do him more damage, and that between neighbors the damage was of no, importance whatsoever. And so in a comparatively short time the idea got abroad that I was not really half as bad as I looked, and that I might in time be really a creditable sort of an acquaintance. But it was the purchase of the wheelbarrow that really broke down the barriers of distrust and suspicion. When I came there, like all new agriculturists I bought a large number of minor farming utensils, such as spades, shovels, hoes, a lawn-mower with a hood, forks, a lawn-roller, a scythe, bush-hook and snaths, double-handed saw, hammer, axes, hatchets, and a pigeon-holed box of assorted nails, and last and most important of all, a fine, new, five-dollar-and-fifty-cent wheelbarrow. To a neighborhood the members of which had for the most part inherited their tools from long-deceased ancestors, an opportunity to borrow new and modern farm implements is a rare opportunity, indeed, and the ice-bound fetters of reserve began to warm up a little and thaw to quite an appreciable extent. In such a neighborhood a bright, new, sharp hoe is a mighty power to make and keep a friendship; a loanable lawn-mower will impose more respect than the possession of money; a box of assorted nails will do much to atone for the errors of a misspent life; a roller for lawns and gravel-walks wields an immense influence for trust and affection. But it is a wheelbarrow that inspires love and good-fellowship. It is a wheelbarrow that levels all ranks, buries all hatchets, destroys all enmities, absolves one from all sins of commission and omission past, present and future, makes one a man and a brother, a comrade, a friend, and a trusted neighbor. Within a month after the purchase of that wheelbarrow I was one of the most popular men in the community, free to borrow anything, from money to elderberry wine, of which the neighborhood had endless store. To me, to my wife, to my children, to my man-servant whom I occasionally hired for a few hours, to my maidservant of a more permanent nature, to my cattle and the stranger within my gate, that wheelbarrow was the most profitable investment I ever made. Did I send a pitcher of cream to a neighbor, it was followed in a day or two by a sort of cross-counter in the shape of a box of fresh strawberries. Did I send a setting of eggs from my choicest fowl to another neighbor, he promptly retaliated with a bunch of delicious radishes or a couple of heads of lettuce, and honors were even. But I had things all my way with the wheelbarrow, for I was the only one on the street who owned one, and so, like the small boy who owns the ball, I was the pitcher on the nine until a new boy came along with a better ball. By these simple and effective means did I remove from my neighbors' minds all suspicions engendered by my past life in other quarters of the town. Yet the one great exploit that put me into a very warm place in the hearts of my neighbors, was the slaughter of the neighborhood dragon, the thrashing of the long-time bully of the little community, the clipping of the wings of the village condor or bucolic harpy, that for years had defied public opinion and outraged neighborly good feeling, and whose name was used to terrify refractory children into obedience. I was warned of this dragon when I bought the farm. I was told that he had made trouble for all his neighbors, was at his worst in litigation, would provoke a saint to retaliation and then prosecute him for it, and keep him on the gridiron of suspense, attending court after court until he wore him out; that, if he wanted anything, he always got it, and that, if he once got down on a man, he was his enemy for life; that he was down on me, — why, I did not know. These warnings however had no great weight with me. Indeed, they did not trouble me at all. I had never had any trouble with the dragon and saw no reason why I should have. I had come to the neighborhood with the honest intention of being friendly and accommodating toward all my neighbors. I was genuinely interested in the community. I expected to contribute according to my means to any subscription for neighborly interests; to subscribe my name to any petition addressed to the authorities for the betterment of the local roads and lawns, trees and sidewalks. At the first sign of foreign invasion I would, and fully intended to, reach down from the wall over the fireplace the old musket and the powder horn that my great-grandfather might have shouldered in the Revolution, had he been patriotic enough to attend that little festivity, and sally forth as did our sires at old Thermopylć. Did the boys from other and alien neighborhoods invade with snowballs, green apples, or brickbats, I would send my first-born to do battle, urging him not to come back but upon his shield. Did the young ladies of our neighborhood vie with the Court-Streeters, the Front-Streeters, or with similar young ladies from other quarters of the town, I would cheer hoarsely for our side and contribute lemonade, pickled limes, slate pencils, and other delicacies peculiar to very young ladies. Did the Decoration Day parade propose any other route of parade than through our street, I would fight their modest appropriation until they acquiesced in the observance of our time-honored rights. Did the street commissioner run his snowplough over Elliott, Grove, Linden, or Court Street before our street, I would have something to say in relation to that anxious, unhappy, and much-badgered gentleman's reelection. In short, I had come to Pine Street prepared to cast my lot with the Pine-streeters, to espouse their quarrels, to share their joys. In time of war to "cry 'Havoc!' and let loose the dogs of war," or to cry anything else that might be more intelligible to the modern dogs of war, or appropriate to the circumstances. In times of peace, to raise white-winged pigeons as emblematic of the idealistic conditions. And with such peaceful intentions I most certainly did not expect trouble with any one. The Dragon's name was Cyrus Pettigrew. Not a handsome name, and Cyrus looked his name if any one ever did. He was old and gnarled and dried and wrinkled and rusty. He was mean and skimpy and avaricious and penurious and grasping. He was harsh and sour and contrary and selfish and grumpy. But I had no fear of trouble. I usually had no trouble with any one. It may have been in a measure due to my profession, for few men care to pick a quarrel with a lawyer. It may have been in a still greater measure due to my avocation, for the men who will risk being embalmed in a newspaper or magazine roast are still more rarely found. Whatever .may have been the cause the fact was undisputed. I was a peaceable man and lived a peaceful life. But the man never lived who could reside next to old Pettigrew and not have trouble with him. Poor old Cyrus, — he is dead now, and, "De mortuis nil nisi bonum" notwithstanding, I have never found man, woman, or child that would own to a passing regret at Cyrus's departure. My first meeting with Cyrus as a neighbor was trying. I wanted a new fence between his place and mine, and I sought him one day near the old boundary fence. Cyrus met my proposition very coldly. He didn't want a fence. The fence had been good enough for him and my predecessor for a good many years. And he didn't think much of an interloper who wanted to change everything over. In vain I argued the necessity of an up-to-date wire fence. Cyrus would have none of it. I finally offered to pay the entire expense. To this Cyrus, who had a sharp nose for a bargain and a pair of exceedingly sharp and far-sighted eyes for his own interest, agreed, although very grumpily. Having obtained his consent I lost no time in buying posts and wire-fencing, and in hiring a carpenter, sappers, and miners, and starting the work. At this time I was called out of town for a few days, and on my return found to my great pleasure that my new fence had been erected and the carpenter was just leaving. I went out at once to view it and to rejoice in the great improvement, and judge of my disgust and wrath when I found that the grasping old rascal had made the carpenter put the new fence more than a foot on my land, the whole length of the division line. After a vigorous speech to the propitiatory carpenter, in the course of which I coined several entirely new objurgations appropriate to the occasion, I jammed my hat to my ears and made for Cyrus's house. I was boiling with rage, and fortunately for us both Cyrus was not at home. As I came back, better thoughts began to take possession of me. The strip of land wasn't worth fighting about. I had made up my mind not to have any row with my neighbors, and here I was, exploding like a paper bag the first time any one got under my guard. The old scamp had certainly scored on me, but I would keep my eyes open in the future. So I made up my mind to forget it, or at least, if I could not forget it, to take no action and to say no word. A short time after this, some of my hens got out and into his yard. There was nothing growing at the time, and they certainly did him no damage. But when I came home, I found three dead hens on my side of the fence, that he had shot and thrown over. This so "riled" me that I promised profanely to have his scalp nailed to my barn-door if it took a leg. But upon sober second thought I dressed the hens, sent them to him by my son Dick, with a polite note of apology for the trespass, and a promise to look after my hens in the future. I hoped for one of two results from this course. First: that he would be so overcome by my magnanimity that he would seek me out, ask my pardon, and endeavor to be a loyal friend for life. Second: If he did not do this, that a bone of one of those deceased biddies would stick in his gnarly old throat and choke him to death lingeringly and horribly. Neither result happened, however. The old wretch had a habit of squinting down the line of the new fence, as if still doubtful if he had got quite as much of my land as he wished; and as he took occasion to do this when I was down in the garden, it was perfectly evident to me that he was trying to aggravate me into hostilities. This I resolved not to allow him to do. But, alas for my good intentions! trouble came. Dick, a young chap of seventeen, one day went across the line for a baseball that had fallen on old Pettigrew's land. He had to pass nearly to the centre of the old man's garden, littered with dead vines and stubs of last year's corn-stalks, when forth from the barn came the old man on the run, with a heavy whip in his knotted hand, and made directly for Dick, breathing slaughter. Now, this was a little too much, and in a second I had dropped whatever I had in my hand and had rushed to the fence with the intention of vaulting it, disarming the old man, and walking him Spanish back to the barn for a little heart-to-heart talk, when a surprising thing happened. Dick, instead of running, as I supposed he would, — for the spectacle of a man of sixty, armed with a bull-whip and bearing down on one with curses is rather formidable to a boy, — stood quietly, awaiting his approach, with his left hand in his pocket, but with the right hanging at his side clinching the baseball. I was near enough to see a look in his face and a glitter in his eye that I knew meant fight. Old Pettigrew, seeing that Dick did not retreat, slowed down to a walk, and then stopped. "Git offer my Ian', ye whelp of Satan, or I'll cut ye tew ribbons!" said the old man, with a fearful curse. "I 'm going to get off your land, Mr. Pettigrew," said Dick; "but if you raise that whip again I'll smash in your old ribs with this baseball and whale you so your old hide won't hold water; now get out of my way!" And he stepped directly toward the old man, who was between him and the fence. "Don't ye peg that ball at me or I'll have ye arrested," said the old man, backing precipitately as the young chap approached.

Dick said nothing further, but leisurely walked to the fence, vaulted over, and came face to face with me. "Good boy, Dick!" I said, as he looked up in surprise and some sheepishness at getting caught; "I did think you were in for a warm time." "Huh!" said Dick, "that old cuss, — I could lick two of him. Hear him swear," he continued. And indeed the old man was giving the best imitation of the army of Flanders I had ever heard. He danced up and down and threatened every sort of vengeance a distorted mind could think of. We paid no further attention to the wretched old man, but left him to cool off. I was too much pleased with the unexpected fighting qualities of my first-born to care enough about old Cyrus to listen. To tell the entire truth, I was the least bit disappointed that the old man had backed down so promptly, for I possessed a deal of curiosity to see Dick in action. A few days afterwards, a dog that occasionally came to the house, an inoffensive, good-natured, trampish animal, was shot on the old man's land and probably by him, although nobody saw him do it. We heard the shot at dinner, heard the agonized yelping of the poor animal, ran out and found him dying in the rear of the old man's house. Dick and I did not hesitate to go across the line and bring the poor old fellow back. He died before we got him over the fence. Nobody interfered with us, and I think we were both hugely disappointed. If the old man had appeared I think some one would have been hurt. Nothing makes a man more wolfish than to see a pet shot to death, and dying with wide-open, pleading eyes and panting, choking breath. We buried the poor animal under an apple tree in the orchard. During the first spring, summer, and fall, old Cyrus exhausted every device to annoy us. In the spring, if the wind blew in the direction of our buildings, on that day he would light a huge bonfire of damp matter and send dense clouds of smoke over us. Finding that this did not annoy us particularly, as the smoke of spring bonfires was very agreeable to us, he would put on an old horse-blanket, a few shovels of stable manure, or a dead hen, and raise a stench that nearly stifled the entire neighborhood. He never failed to shoot one of my hens if it escaped from the yard and trespassed, but after the first experience I no longer dressed and sent them to him. But on one occasion, when his hens got out and strayed on my premises, I carefully drove them back unhurt, only to be accused of purposely letting them out. During the second winter he could not annoy me as much, but every mean insinuation that malice could invent or distort, he made. It was in April of the second year that I got him hard and fast, and by the merest chance. I had in the previous September bought my Jersey cow. I was very particular about her appearance, curried her every day, bedded and blanketed her, and indeed cared for her as well and painstakingly as I did for Polly. The custom of the local farmers was to allow filth to accumulate on their cows' flanks and legs, until it hung from them in crusty scales, to peel off in the spring with the shedding of the old coat. The care I gave my cow made her coat shine like satin, and certainly lent a relish to her milk. In April her old coat became dull and dead, and she began to rub it off her head and neck in patches, disclosing a close new coat of cream-color where the winter coat had been a light chestnut. One morning, in rubbing her down, I found that with my fingers I could pull the old coat off in tufts, and that she apparently enjoyed having it pulled. Without really thinking of what I was doing, I wrote my initials, H. A. S., on her back by pulling out the dead hair. Seeing how easily I could do this, I drew, or rather pulled, on her side near the curve of the belly, a grotesque figure of a small boy, then a circular brand on her shoulder, and three X's on her flank. Then I quietly led her to the hitching-post at the side of the house and awaited developments. In a moment my wife came to the door, with wide-open eyes. "For gracious sake what have you been doing to that cow?" she demanded. "Oh, nothing," I replied, "that's the way range-cattle are branded. This cow had a good many owners and evidently each one branded her," I further explained. "It's no such thing," she retorted hotly, "you did it yourself. That explains why she bellowed so this winter." She had bellowed a good deal when I took away her calf, but I did not say so, for I always liked to get a rise out of my wife. "I think it is just horrid in you, and about the cruelest thing I ever heard of, and you have just spoiled her looks." Now out of the corner of my eye I could see old Cyrus peering over the fence and listening gloatingly to the conversation. After giving him time to satisfy himself thoroughly, I led the cow back to the barn, followed by my wife, and there illustrated the matter by drawing on the off-side of the animal a serpent and a circular brand, while that delighted animal stood with eyes half closed in ecstasy. Much relieved and amused, my wife went back to the house, laughing over the ridiculously decorated animal. After milking the Jersey, I led her out and tethered her in the sun in full view of old Cyrus's premises, and finished my breakfast. On my return to lunch I was informed by my wife that the old man had been looking at the cow from over his fence, in company with several men, to whom he was talking with excited gestures. This amused me so much that I laughed loudly. But I did not for a moment anticipate the far-reaching results of my joke. I only thought it an excellent joke on the old man, as it had been on my wife and my daughter and Dick. That night I was to give a lecture in a neighboring town, and departed on the afternoon train, intending to return in the morning. I had an excellent audience, an enthusiastic reception, and a very flattering introduction. Just as I had made my bow and was about to begin, a man whom I knew to be a deputy sheriff stepped on the platform, placed his hand on my shoulder, and informed me that I was under arrest. I am sure I was never so astonished in my life. If the audience had suddenly risen in the air like the card people in "Alice in Wonderland," I should not have been more surprised; nor do I believe the audience would have been, for his words were perfectly audible and he was well known to them. For a full minute I must have stood staring at him. Then I asked for his warrant, and he handed me one. I opened it and found it was regularly issued by a justice on a complaint signed by old Cyrus Pettigrew, charging me with "cruelty in burning, cutting, branding, and otherwise torturing a certain Jersey cow then and there in my charge and custody, or wilfully permitting and allowing said animal then and there in my custody as aforesaid to be burned, cut, branded or otherwise tortured." In a flash the whole scheme dawned on me and I could not help admiring the old rascal's devilish ingenuity in planning the details, and at the same time his inevitable disgust and fury when the truth was known. In the meantime I was in the most unpleasant and ridiculous position imaginable; but one's mind works quickly, and I instantly told the audience that I was arrested for cruelty to animals, that if they would kindly watch the papers for the outcome of the trial, which I was sure would be interesting to them, and defer judgment to that time, I would fill my engagement and finish my lecture. The audience applauded, the sheriff took a seat on the platform, grinning good-naturedly, and I began my lecture. I was thoroughly keyed up to the occasion, and so filled with laughter as the possibilities of the situation dawned on me, that my lecture was really very funny, and, as the audience said, exceedingly entertaining. Indeed, at its close they crowded about me with offers of bail or assistance of any kind. I thanked them most heartily, and, accompanied by the deputy, went to my hotel, where I engaged a room with two beds, he having very indulgently agreed to stay with me at a hotel rather than to load me with chains and incarcerate me in the local lock-up, which was indeed very good of him. I chuckled to myself to see the care with which he chose the bed nearer the door, looked at the fastenings of the windows, locked the door, and put the key under his pillow. And so, after undressing, I lay down peaceably on the other bed, and having no guilty conscience, fell asleep. I am afraid my keeper did not sleep as soundly as I did, for I have a vague recollection of his lighting the gas several times during the night, and peering at my recumbent form, to see if I was really there. And thus did we spend the night. |