| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER XIX

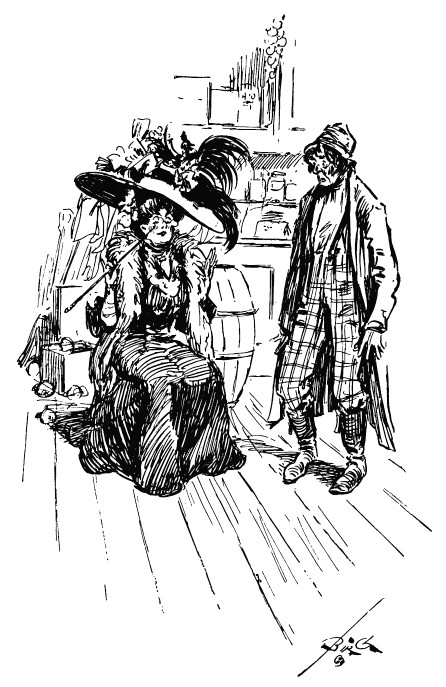

AMATEUR THEATRICALS I BELIEVE that a country town or neighborhood can receive no greater benefit than in the introduction of new blood. My brief experience as a farmer has taught me this, and my long experience as a citizen of a country town has convinced me that in no way can a country community make good its loss of young men who have an ambition awakened in schools and colleges to go to larger communities, than by offering every possible inducement for young men and women to come in from other communities. For instance, if Ike Peterson's son Bill goes to Boston or New York or Seattle or Chicago, and becomes an active and influential member of the law firm of Strasser, Ellis & Co., our town has lost one who might have been a useful citizen. But if at about the time of Bill's departure, the junior member of the selfsame firm should, curiously enough, decide to quit the city for life on the farm, or amid semi-rural surroundings, and, more curiously still, should decide to become a free lance in the same community that Bill has quit, why then we "break even," to use a sporting phrase, at least so far as number goes; but in reality we are better off, for we get a citizen with advanced ideas, imbued with the hustling spirit of city life, which cannot fail to have an influence for good on the small community. To be sure, New York or Seattle or Chicago or Boston has Bill, which we hope is a good thing for them and for Bill. But the effect of Bill's invasion is not immediate or in any way disturbing to the urban community. But if, instead of the junior partner of the firm, the young and zealous assistant pastor of one of the churches of Seattle or Chicago or Boston or New York becomes pastor of the local Congregational or Baptist or Unitarian or Episcopal Church, why then we go Chicago or Boston or New York or Seattle "one better," as the moral status of the community is jacked up much more effectively than that of Boston or New York or Seattle or Chicago is on account of Bill's arrival. By this means only is the professional, social, financial, and moral balance preserved. Now we have had accessions to our neighborhood. I disclaim modestly any responsibility for the fact, for the new neighbors would undoubtedly have come had we not lived there. In fact, one of the neighbors came in spite of my repeated warnings, showing how little he cared for my opinion. It was in this way: one day a sturdy, stocky, auburn-haired (I am better acquainted with him now and call it red) young fellow came into my office, and wished to see me for a moment. I knew he was in no trouble, for he was too fresh and bright-looking. I knew by his well-bred, respectful manner that he was no book agent or seller of patented articles. So I willingly dropped whatever I had on hand, and invited him to the inner office. He showed his directness by coming at once to the point. "I am a doctor and wish to settle in your town. Is there a chance for me?" "Mighty little, I'm afraid; there are Doctors Blank, Dash, and Hyphen, and Brackett, and Comma, and Colon, allopaths, Doctors Capital and Lowercase, homoeopaths, two college veterinarians, half a dozen amateurs practising in violation of law, and several old ladies without waistlines who are popularly supposed to know more than all the doctors in a certain class of cases." "Gee!" replied the young man, "it don't look very promising, does it?" "Not unless you are a good doctor and have money enough to wait," I replied. "Well," he said slowly, "I think I am a good doctor. At least I have been through a good deal of preparation. But as for money, I have enough to fit up a house and office, and wait perhaps six months. How many of these doctors own automobiles?" "Three," I answered, "and the rest have horses." "Hm," he said, "that looks better. If they can all afford horses, I ought to be able to get along by walking or using a three-year-old bike." "Well," I said, "you might. But I think you had better try some other place. By the way, come to lunch with me and I will talk it over with you." "Thank you, no," he answered. "I am going to look the town over and see what I can of it before taking my train to Boston." And after offering a fee, which I declined, he thanked me and withdrew. I had nearly forgotten him when one day he returned, bringing with him a very attractive young lady whom he introduced. Although they were well-bred and consequently not in the least demonstrative, it was at once evident that they had more than a passing interest in each other. As before, he came to the point with his usual directness. "Well, Mr. Shute, I have considered the matter of settling, and I have decided to come to Exeter." "Bully," I replied in the expressive slang of the period. "I think you are making a mistake, but I like your grit and I am glad you are coming; for Exeter, like all country places, needs new blood and new ideas. Now what are you going to do about quarters?" "That 's just what I want to see you about," he said. "And it is the most important thing of all!" And I rapidly gave him the names of several places I thought he might get, among them an attractive little house not far from mine. The next day I found he had engaged that place, and a few days later he began to move in his furniture; but I saw nothing more of the young lady for a while. The other addition to the neighborhood came rather suddenly, for one day in the early fall, on returning to the office, I saw in front of a neighboring house an immense van of household goods, an excited father, a helpless mother of a large family, a colored servant and six or seven children, watching with devouring interest two brawny policemen who were forcibly removing two very drunken draymen from the vicinity with prodigious exertion, in which catch-as-catch-can, Grćco-Roman, collar-and-elbow, hitch-and-trip, "side holts," grapevine twists, hammer-locks, cross-counters, straight lefts, jabs, upper-cuts, pivots, and other technical manśuvres of the ring and mat alternated with one another in bewildering rapidity, and a quality of language was being handed round that would chill the blood of a pirate. Now two men, however big, strong and willing, cannot readily, and without assistance, subdue, handcuff, and abduct two other men equally big, and, further, inspired by a mixture of wood-alcohol, fusel oil and other powerful stimulants, known as curry-comb whiskey, even when the two first-named gentlemen are clothed in the majesty of the law, blue coats, brass buttons, and helmets that rest mainly on their spreading ears. And so, as a law-abiding citizen and a magistrate, it was my duty to go to the assistance of my officers and to deliver them from their enemies, which I did, without much enthusiasm, however; and with the assistance of a lusty peasant who came by in a farm-wagon, and the excited father of the family, we soon had the miscreants safely trussed and piled into the farm-wagon, which was pressed into service with the horse and the driver. This accomplished, and the prisoners having disappeared townwards amid a prodigious rattling of loose wagon-wheels and terrific blasphemy of the chained, I turned my attention to my new neighbors. They were in a very unpleasant predicament. Their entire household goods were in the van, including such supplies as were necessary for immediate use. Luckily it was warm weather, and their night's lodging depended upon their strength and ability to disentangle and reconstruct their household furniture, and night was coming on apace. There was but one thing to do, — to march them all over to my house, there to take pot-luck with us. I was a little more confident than usual in relation to pot-luck, for that morning I had sent home a particularly fine and large roast, and green corn and vegetables were abundant in my garden, and milk and eggs were always at hand. My wife and my children, who had arrived in time to see the closing rally when we "flopped," as Dick expressed it, the draymen, somewhat to his disgust, as he came just too late to take an active part in the struggle, added their eloquence, and we finally persuaded the entire family to accept our hospitality, and after a hearty supper, we set to work on their goods. How easy it is to work for other people when you are doing it out of neighborly good-feeling! How ingenuity is awakened that you thought you never possessed! Beds were put together that in the annual spring-cleaning would have defied us. Stovepipes were fitted that under ordinary circumstances would have made a tinsmith become a gibbering maniac. Stoves were lifted and pushed into place that would have made Hercules' labors seem like basket-ball. By nine o'clock the beds were up, the carpets in place, but not tacked, the range drawing like a furnace, the yet unbroken crockery arranged on the shelves, pictures hung, and, what was best of all, we had become in those few short hours better acquainted with each and every member of the family than we would have been had they lived there for years; and their opinion of our town, which had been steadily going down from the moment they left their old home, had mounted to a really undeserved height. Indeed, when at a late hour we dragged our tired legs upstairs to bed, we felt that we had really done something worth while, and realized how thoroughly we would have appreciated a little attention of the sort when we entered an alien neighborhood. The next morning the entire family of children were over in time to see me milk the cow and rub down the horses, and as they had never seen anything of the kind before, I was compelled to answer about a thousand questions before they fully understood matters. Up to this time the neighborhood had been emphatically not a neighborhood of children, but rather a neighborhood of dignified elders, and the addition of a half dozen of irrepressibles did much to enliven things. To be sure their advent was regarded by the neighborhood with mixed feelings, in which distrust was a predominating ingredient; but the neighborhood had successfully weathered our invasion, and as some of the most conservative said, "We have seen worse things, and have lived." All this time the young doctor had been painting and papering his little cottage, impaling himself on tacks and wire nails, abrading his shins against sharp corners, raking, mowing and sodding his lawn, and getting himself into very serious complications indeed with paint and glue and oil and wax and adhesive paste, and lawn mowers that wouldn't mow and hammers the heads of which flew off and broke the chandeliers, and rakes which he stepped on and which flew up and hit him grievous blows on the brows, and faucets which he forgot to shut off and which leaked all over the front-room ceiling, which fell down on his head, and shut-offs that squirted ice-cold water up his sleeve and down his neck, and flat baskets of crockery and china over which he fell with terrific crashes and unexpurgated oratory, and which he subsequently tried ineffectually to piece together with cementine and fish glue, and finally buried in the back yard. I admired and pitied the doctor and loaned him everything I could think of in the way of tools and supplies and cheerful comment and disinterested advice, and physical assistance in the way of personal services of myself, my wife and children, my horses and my cow and the stranger within my gate. I also introduced him to every one I could, and spoke of him as an eminent practitioner, and did every thing I could to advance his interests, without of course sacrificing my own. But the doctor, while working like a cart-horse in the dusty present, was living in the future. What if his hands were blistered and grimy, his hat dusty and dented, his trousers, once immaculately creased, worn to transparency at the knees, his lungs clogged with dust, his throat hoarse with powdered plaster, cellar-damp and the raucous hissing out of anathemas on various things, he was happy, because he was working for some one. His preparations advanced toward the goal of completion, and the doctor announced a vacation for a week, after which he would bring the attractive young lady to visit her new home before the wedding-day arrived. Upon this we promptly asked him to bring her to our house, but found that our neighbor Daniel had stolen a march on us. We contented ourselves with finding out from the doctor the exact day of her visit, and began to lay plans to make her introduction to her new neighbors memorable. So I called a meeting of the neighborhood at my house for a certain evening, and to make it more interesting provided refreshments which included strong coffee, as the affair was weighty and of great importance. The two delightful old ladies arrived, escorted by their servant, who delivered them into my charge with a good deal of formality, during which I bowed over their mitted hands until I felt my backbone creak and then gave them my arm up the steps, while they smiled and turned out their toes gracefully as they minced up the path. The two old gentlemen arrived with somewhat rusty but perfectly proper black coats of a variety of basket-cloth popular in the early seventies, double-breasted and with narrow shoulders, and they bowed with fine old-fashioned courtesy to the ladies, and sat upright in the stiffest-backed chairs they could find. Daniel rolled in with a jolly joke which delighted the old ladies, with whom he was a prime favorite. After the company had gathered, the nature of the business was disclosed and a great variety of suggestions was offered. Daniel suggested the purchase of a small, handsome and safe horse and phaeton; the generosity of which proposal filled us with admiration, while its probable expense appalled us, and his proposal was rejected with few dissenting voices, among which Daniel's was the loudest. The Professor opined that a handsome dinner-set would always be appreciated. The neighbors all agreed to this, but as prevailing opinion appeared to be in favor of doing something original, the proposal was voted down, with apologies to the Professor. The two old ladies thought an old-fashioned sideboard or highboy would be a good thing. We all concurred in this with great enthusiasm, but as nobody present was willing to sacrifice his antique furniture, and as the entire crowd were in a state of deep financial depression, the idea was abandoned. Cut glass was beyond our means, silverware out of date, if not ditto, tin and wooden more suitable to our station in life, and so we decided on tin, wood, leather, zinc, and brass. How to give them? was the next question. This caused great discussion, in which all members took an active part. One of the old-fashioned gentlemen, however, made a tremendous hit with his speech. Drawing himself up to his full height and placing one hand on his hip and flourishing his pince-nez with the other he thus addressed us: — "Fellow citizens,—ah, friends and neighbors, the felicitous — ah, nature of the coming event, which casts, not shadows — ah, but radiant arrows from Cupid's bow," (great enthusiasm and applause), "is the r-r-r-rgmm, little touch of nature that maketh the whole world kin — ah, (applause) the hope — ah, of posterity — ah, inherent in the breast of man —ah, (deep blushes mantled the cheeks of the old maiden ladies) make it incumbent upon us — ah, (violent tugs at his coat-tail by the other old gentleman) to celebrate this happy —ah, event in a somewhat unusual — ah, way. I beg leave to move that some happy — ah, representation, such as a play, be written by some —ah, talented member of our body-corporate — ah, and be produced at some —ah, favorable time, when all could take part." (Terrific enthusiasm; prolonged and violent applause.) A play, that was just what we wanted. We would have it a bucolic play, because we were a neighborhood of farmers, by avocation at least, and she was from the city, and should learn to take us as we were. We almost forgot our refreshments, so interested were we in planning details, appointing committees, assigning parts in advance, without in the least knowing what the play was to be. Finally, after prodigious discussion, and huge consumption of fruit-punch, coffee and sandwiches, we decided to purchase a quantity of kitchen-ware of wood, iron, and tin, and I was ordered, under terrific penalties, to produce a play deftly woven round these homely articles, having for its scene some rural forum such as the country store, the post office, the town-'us or the school-'us. The evening came, the neighbors arrived. There was the hurried moving of stage props, a terrific hammering behind the curtain, calls for hammers, nails, and laths, entreaties to "get off my head!" sarcastic reminders to "kindly step off my fingers"; queries as to "where are you going with my step-ladder?" and "who had the rouge last?" mingled with occasional and fearful crashes as hurrying people with stage furniture collided, and a general alarm when the curtain suddenly blazed up from a careless candle. In front of the curtain chairs were being arranged in convergent rows. Rocking-chairs, leather-backed chairs, lounging chairs, dining-room chairs, kitchen, old derelicts from the attic, splint-seated from the store room, and every kind and nature of hassock and footstool. People were arriving and greeting one another in shouts, the noise behind the curtain being such as to render communication in the ordinary tone of voice impossible. Finally, the uproar ceased and the hoarse tones of the stage-manager subdued to a husky but perfectly audible whisper were heard to order every one off the stage but the stage people, for the curtain was "goin' up in about three seconds." There was a scurrying and giggling, a heavy fall and a burst of half-stifled laughter, and then the curtain rose very jerkily and disclosed: — SCENE: A Country Store.[Counter, hams, rubber-boots, wooden pails hanging from the ceiling, advertisements tacked to the walls, stenciled adv., etc., steel traps, sign, W. I. Goods and GroceriesTIMOTHY G. SEED [Within, MR. SEED, in linen duster, brimless straw hat, leather boots with trousers tucked into the legs, chin-whiskers and rich brown wig, is busy chasing the cheese back into the cage. Mr. Seed. — Dang this 'ere pesky cheese, 's allus gittin' aout a' skally hootin' raoun' rite afore customers. Seems so the old scratch was in the cussid stuff. (Thumps cheese with pork-barrel stick.) Thar, dum ye, guess naow ye air stunted, ye'll lay quiet a while. Ezry! Ezry i whar is that dumbed worthless boy, Ezry! [Enter EZRA: boy, jumper, shortish overalls, one suspender fastened with a nail, boots turned over at the heel, chewing and swallowing something. Thar ye go, allus eatin' suthin'. Been at them dried apples agen? 'Fi ketch ye eatin' any more dried apples, I'll skin ye alive. It's a wonder they don't swell up 'n' bust ye. Hey ye sanded the sugar, Ezry? Ezra. Yessir. Seed. — Hev ye watered the milk? Ezra. — Yessir. Seed. — Hev ye counted over the coffee? Ezra. — Yessir. Seed. —Hev ye aired the salt fish? Ezra. — Yessir. Seed. — Hev ye giv the butter a good combin'? Ezra. — Yessir. Seed.—All rite, then; I want ye to go daun to Ruta J. Bagas and tell him we draw the line on eggs that have been set on fer nineteen days. When eggs peep so 's everybody can hear 'em it spiles the sale, 'n' we hey to use 'em to hum. Stop at old Miss Grandiflora's 're tell her we got some o' that cookin' butter that 's a little spiled, but good enough for a church sociable. [Exit EZRA, whistling; Mr. Seed goes to desk and begins to charge up items. Seed. —Pumpkin J. Radish, two pounds butter. That butter 's a little spiled, but Pump 's used snuff so long that he hain't got no taste 'n' can't tell the difference, so Pump gits charged full price. Hardy P. Shrubb, half peck o' potatoes, half pound o' cheese. Lessee, wuz it the jumpy kind, or the deef 'n' dumb kind. Oh, yes, I remember Hardy, he sez it got away from him on the way hum 'n' got away into the bushes. I forgot to stunt it afore he tuk it away. [Enter TEMPERANCE S. RHUBARB. Angular female, with Paisley shawl, specs, mitts and beaded reticule. Seed. — Howdy, Miss Rhubarb: nice day. What kin I dew for ye to-day? Got some nice bombazine jest in. Right from East Rochester; think ye 'd like it. Temp. — No, thank you, Mr. Seed, I 'm on a very different arrent to-day. (Giggles girlishly.) I want to buy weddin' present. Seed. — Ye don't say so. Ye beant goin' ter git married, be ye, Miss Temperance? Temp. (bridling). — Well, I'm sure I don't know why not if I wanted to. Seed (hurriedly). — No reason 't all, Miss Temperance, ye might hey hed all the young fellers here if ye 'd wanted 'em. Temp. —Ye know I hed my bereavement. (Wipes eyes.) Seed. — Yes. (Sighs heavily.) Temp. — Now what ye got cheap in wooden goods? Seed. —Got a nice choppin' block off that big ellum tree. Temp. — Well; the idea — choppin' block! Guess he thinkin' 'baout suthin' besides choppin' wood. Seed. — That's what he'll be doin' for the rist of his born days. Sometimes it's a mighty 'scape-valve for the feelin's when company 's raoun 'n' ye don't take it aout in cussin'. Temp. — Well, I guess these two won't ever feel that way. They are just tew little love-birds. It's beautiful to see them. (Clasps hands ecstatically.) Seed. — Shaw, they'll fight sure. Love-birds is the crossest critters I ever see. They screech and fight like tarnation cats. I had tew onct. Set on the roost with their heads close together. Well, they screeched, 'n' fit, till one killed 'n' et t' other. Temp. — Well, this couple is different. So lovin' and trustin'! Seed. — What yer say to spoons. Seems thet's what they be. Temp. — Just the things. Two lovely wooden spoons. Show me the best and cheapest. (Opens reticule.) Seed (diving into corner, finds spoons with difficulty, dusts them, blows on them, and wipes them on his trousers). —There, ye kin hit an awful lick with one of them. When them tew love-birds gits inter a scrap it's a good thing to hey suthin' handy. Temp. (scornfully). — I wouldn't be sinnatin' sich things. Ennyway, I'll take these two. Seed (sarcastically). — One'll be cheaper, and them love-birds kin eat outer one, (aside) for a while. Temp. — Thanks. Five cents. (Pays, perks, and departs.) Seed (peering from window, soliloquizing). —Well, here comes old Hen Peck 'n' his wife, drivin'. Well, Hen he was a love-bird onct. Don't look like it naou. 'Member how tarnal soft they wuz; et from the same plate at sociables, 'n' drinked from the same glass at picnics, 'n' naou old Mis' Peck won't let poor old Hen set to the table, 'xcept when they is company. Hen Peck (entering). —Howdy, Tim. Seed. — Howdy, Hen. Pretty good day for the time of the year. What yer goin' to buy to-day? Hen. — Nothin' much. Want some kind of a weddin' present. Suthin' cheap. Seed. — Won't Mis' Peck come in? Hen. — No, she's bad with the rheumatiz. Seed. — What kind of a present do ye want? Hen. — Wall, rat pizen er Paris green's the best thing for both on 'em. Seed. — Shaw, don't talk so, Hen. 'Member you 'n' M'randy wuz love-birds onct. 'Member haou ye used to drink from the same glass 'n' eat from the same Hen. — Shet up, Tim! I swanny, wuz I sech a dummed fool ez that? Look at me naou Do I look like a love-bird? Seed. — Not much, Hen. Wall, what kind of a present d' ye want? Hen. — Suthin' cheap. Wooden ware, M'randy said. Seed. — How 'd a rollin'-pin do? Hen. — Jist the thing. Ye can hit a almighty tunk with it. Sometimes seems 's if I could knock M'randy's head off 'n her. But she allus gits it first. Voice from without. — Henry Peck, be ye goin 't' get that present or beent ye? I don't want to haf tu speak t' ye twist. Hen. — Yes, my dear, comin'. For the land sake, don't be so tarnal slow, Tim. Ten cents; don't wrap it up. Comin', M'randy, comin', my dear. (Exit hurriedly.) Seed. — Poor Hen! M'randy was a likely critter, too. She kind of took a shine to me 'fore Hen begun to set up with her. Sometimes, I almost think she was kind of disappinted in Hen. Naou 'f it 'ad been me, M'randy 'd — Hellow! There goes that pesky cheese agen. Hi tha! shoo! (Jumps up and chases the cheese back to its cage and strikes it with butt end of butter knife.) Well, I've got to put some chloride of lime on that salt fish. (Sprinkles fish.) [Enter PANSIE J. PINK and AUGUST SWEETING. Seed. — Well, Pansie, you look ez pretty ez a Baldwin apple. Ain't thet so, August? August. — You bet, Tim. I 'm goin' t' buy suthin' for a friend of mine who is goin' to be married, 'n' I jest bet Pans'll git suthin' good. I got two dollars 'n eighty cents, 'n' I don't keer fer no expense nor nothin'. Pansie (very modestly). — How much are bread-boards? August. — Bread-boards nothin', Pans; git 'em some napkin-rings or a pipe, or pen-wiper, er suthin' useful. Pansie.—I want them to keep what I give them, and use it too, and I don't know anything more useful than a good bread-board. I'll buy a bread-board and you can buy whatever you want. How much is this bread-board, Mr. Seed? Seed. — Twenty-five cents, Pansie, and it'll wear. Sound 'n' solid, just like you, Pansie. Hope I'll hear about your gettin' married soon, Pansie. Pansie (with a 14-carat, three-ply, home-made blush). —Oh, thank you, Mr. Seed, I guess you needn't fear that of me. (Pays and exit.) Seed.—Whot's the matter with you young fellers, August, lettin' that gal escape? Where 's yer eyes? August. — Dumpy, not my style. A feller likes a girl with a little go, a little style. One ye know that can trot in quick time. Naou thet bread-board shows just what she is. Fancy a girl with any go to her giving a bread-board for a weddin' present. Naou, I don't 'ntend to spare no expense, but I want suthin' stylish. Naou, a feller likes a good pipe. A good briarwood. That one'll do. Twenty cents? All right. Kinder high for a briarwood, but I never consider expense when I buy weddin' presents. Neon the picter. Naou that's style, that's finish, thet there picter means suthin'. (Handles with the appreciation of a connoisseur the most frightful print imaginable. Buys print.) There, bread-board be hanged; I like some style to a present. When I get ready to settle down it'll be with some one with some style, but a fellow must have his little fling first, and there 's nothin' like being up to date. (Goes out whistling "Shoo Fly," stops and bows profoundly as Mrs. Grandiflora enters.) There, that's what I call style. (Aside.) Mrs. Grandiflora (in hat of terrific size, flamboyant with feathers, and ribbons in three different shades of red; yellow parasol, and lorgnette made of eye-glasses lashed to tip of bamboo fishing-rod; purple dress, if possible). — Well, good afternoon, Mr. Seed. Seed (coming from behind the counter, dusts chair, places it with profound bow). — Good afternoon, Mrs. Grandiflora. Mrs. G. (seats herself, raises lorgnette to her eyes). —Have you heard of the new engagement? Seed. — There beant another, be they? 'Cause 'f there be, I 'm goin' to lay in a new stock of wooden ware. Mrs. G. — No, no new one, but such sweet things as they are, and so well suited to each other. You know Pope says, "Man is the ragged loafing pine,Woman the gentle jimson vine, Whose scalping tendrils round him twine." But he 's real smart, and she 's just like a jimson vine, just clasping him every chance she can get. Ain't Pope just too sweet for anything? I do enjoy Pope and Bridewell and McAuley. McAuley is just divine, and it was so strange that he should become a prize-fighter afterwards. But, then, literary people are queer just like musicians. There was Sullivan, you know, the prize-fighter, who wrote the most beautiful song about some poor organ-player sitting playing his organ one night, and someone came along and stole a whole load of wood. He had just bought a cord of it, and, poor man, he lost it all and he hunted but never could find it. But poor man, he never lost hope and stuck to it to the last that he would see that cord again. I hope he did, poor man. But about this wedding, — I do want to buy something real simple. I do like simple things. There are some people who want showy clothes and who love to make a show, but I say, give me quiet tastes and literary ability and I don't want nothin' else. When you see flash people drivin' by in their stylish coops and butlers on the front seats, I say to myself, "Volumina Grandiflora, don't you never fret yourself one bit; ain't it better to be able to talk grammary and to be allitery than to make a show?" No, say I, you can have your butlers and your rubber-wheeled carriages and your tigers, if you want 'em, though I never happened to see any tigers, although I looked for them time and time again, and never see anything more 'n some of them spotted damnation dogs. P'raps them is what they meant. Have you read the "Simple Life" by Wagner? You know Wagner, of course, the man who wrote Mendelssohn's Wedding March. I thought I would read it and it would give me some idea of what is the latest thing to do at weddings. Well, about that present,— a good broom, one of those quiet shiny ones with a red label. Send it up, please. (Rises and departs, while SEED, with his hand to his head, staggers to his desk and begins charging up various articles to John L. Sullivan and Wagner Dryden.)  Have you read "The Simple Life" by Wagner? [Enter MISS MULLI GRUBBE and OLD LADY SNAPDRAGON. Black shawls tightly wrapped across their chests — red noses — black lace-mitts with fingers gone — small black straw hats or bonnets' — very erect. Mr. Seed. — Good arternoon, ladies. The ladies (forbiddingly). — Day, sir. Seed (affably but somewhat apprehensively). — What ean I show you to-day? Old Lady Snapdragon (who is deaf, to Miss Grubbe). —What did the old fool say? Miss Mulli Grubbe.— He wants to know what he can show us. Old Lady Snapdragon. —Tell him if we want anything we will tell him. Seed (aside). — I'll show 'em the door for two cents. Miss Grubbe. — What's that? Seed. — Nothin', madam, talking to myself. Miss Grubbe. — They dew say people do that ez they grow old. Seed (aside). — She ought to know. Miss Grubbe. — What's that? Old Lady Snapdragon. —What does he say? Seed (bellowing). — Nothin', madam. Old Lady Snapdragon. — That's whot he's been doin' all his life, talkin' 'n sayin' nothin', but's the first time I ever knowed him t' acknowledge it. Miss Grubbe. — What's the price of ironin' boards? Seed. — Fifteen cents if you want 'em to lay people out on, because you can return 'em. Fifty cents if you want 'em to iron on, 'cause we don't take 'em back. Old Lady Snapdragon. — What 's he say? Miss Grubbe.—Fifteen cents for corpses and fifty cents for live people. Seed (aside).—If you want 'em for the old lady and will use 'em, I give ye one. Miss Grubbe. — Give me a new fifty-cent one. Old Lady Snapdragon. — Can't yer let us have a corpse one that has been returned two or three times, for twenty cents? They'd never know the difference. Seed (bellowing). — No, madam; the last one was returned from a man who had bronical bronchitis, and that 's ketchin' as thunder. (Pay grumpily and exeunt.) [Enter HUNGARIA N. GRASS, her husband, OAT GRASS, local Justice of the Peace, and JOHNNY JUMP UP, son of HUNGARIA a little red-headed boy. Johnny. — O Ma, want stick er candy. Can I have it, can I, Ma? an' some juju paste; can I, Ma? You said I could. [Pulls down barrel of brooms, which in turn brings down tin boiler, lamp and other things. HUNGARIA picks up JOHNNY, boxes his ears soundly, and hands him over to OAT GRASS, who larrups him with his cane. Whereupon HUNGARIA relents, pushes OAT GRASS into an open barrel, where he sticks. She clasps JOHNNY to her bosom and pats his head. SEED pulls OAT GRASS from the barrel with difficulty just as POPPY GRASS, their daughter, enters. Poppy (short dress, bead necklace, hair in two pig-tails, chewing gum and talking as she chews). — Say, Ma, I want some candy, too. Johnny got some, can't I, Ma? [General discussion between members of the family before the matter is finally adjusted by giving her what she wants. While the children are quieted, HUNGARIA asks the price of a chopping-tray.] Oat Grass. — Jest the thing, Hungaria, most convenient things I ever saw. We kin chop up mince-meat, 's neat 's you please, and then mix up a mess of chicken-feed in it, and sometime mighty convenient when we can't find the dust-pan. Tell yer, Timothy, Hungaria is a master-hand to make things go a long distance. Don't know what we ain't used that er choppin'-tray for. Hungaria (who has vainly tried to stop him). 'T is no such thing, Oat Grass, and you know it. They ain't a neater housekeeper round, than I be. [POPPY tries to dispossess JOHNNY of his stick of candy, and the result is a mixup and the children are torn apart by their parents, shaken and set down hard on opposite aides of the store, where they make up faces at their parents and each other. Hungaria. — Be you goin' to the weddin', Mr. Seed? We be. It's jest too nice for anything to see young people get married. I only hope they'll be as happy ez we be. We've lived together for seventeen years 'thout never havin' a cross word and if I dew say it, nobody ever had tew such angel children as ours. [Terrific crash heard as POPPY pushes Johnny's chair backward and general mixup results. After this is quelled, chopping tray is bought, paid for, and parents depart, much to TIMOTHY'S relief Timothy (soliloquizing). — Well, if that's their idea of happiness, believe I'd rather be an old bach. Curtain.

The play was very successful, the parts being acted in a perfectly killing manner. The older of the two old gentlemen took the part of Seed, and a professional could not have surpassed him. One of the old ladies was Temperance Rhubarb, and her smiles, smirks, giggles, Paisley shawl, and tiny jointed-parasol, nearly killed the audience, as did the stunning get-up of Daniel's wife as Mrs. Grandiflora. The Professor's wife as old Lady Snapdragon, and the new neighbor's wife as Miss Mulli Grubbe, caused us to hold our sides, while Daniel, the Professor, and the other old gentlemen, sitting on cracker-barrels and discussing rural affairs, kept the actors in giggles all the evening. After the play Daniel and his wife, according to agreement, secured the doctor and the young lady, who were their guests for the evening, bade us good-night and departed homewards, amid our loud protests and entreaties to remain. Then the surprise of the evening was worked. From the attic, days before, I had resurrected a long-disused but able-bodied tuba, had oiled its rusty valves and had practised hoarse harmony until my lips were swollen to sponges. With Dick on an astonishingly shrill E-flat clarinet, one of the old gentlemen on a fife, the new neighbor on a trombone, on which,. by the way, he was a one-time expert, the Professor on a bass-drum, my daughter on the snare, and the other old gentleman as drum-major, we at once headed a procession down the street, followed by all the guests bearing their purchases. We countermarched, and, playing the Wedding March from Lohengrin, fortissimo and at double time, marched into Daniel's house and down the broad hall, where, to the great confusion and amazement of the doctor and the young lady, we presented the entire lot of ware, in sections, and with oratory, to the young couple. They recovered promptly from their embarrassment, and it was a late hour when we left Daniel's weary with well-doing and sated with good cheer. When an entire neighborhood winds up an evening with old fashioned square and contra-dances, with pigeon-wings, Kensington balances and waist-swings; when a gentleman of three hundred pounds' weight goes down the centre with a maiden lady of seventy-eight, like a lithe youth of eighteen with a young matron of twenty-eight, and when two aged but courtly bachelors give an exhibition of ante-bellum dancing that would astonish a modern Papanti, one can readily conclude that performers and spectators are keyed to the highest pitch of enjoyment. Indeed, the play and the dance were so enjoyable that the evening was but a precursor of many other evenings of similar enjoyment; and before the week was past a meeting was held at the old gentleman's house and an association formed known as the "Masque Club," in which plays are recited periodically, with the book and with no further preparation than one reading; and the talent that had lain dormant for many years in that neighborhood has been awakened to life, and wields a vast influence in the welfare and enjoyment of the local populace.  Dancing that would astonish a modern Papanti |