| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

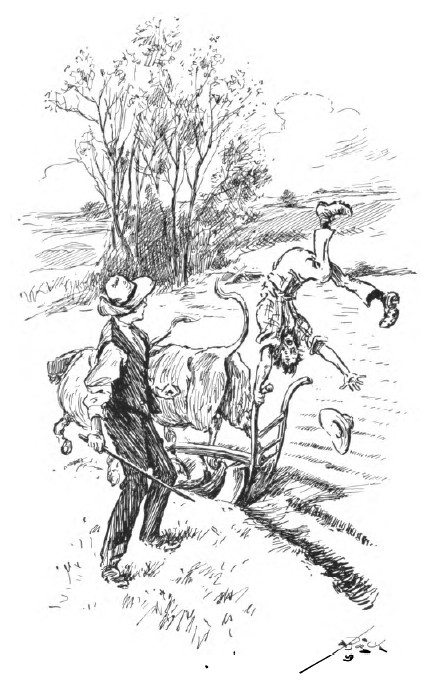

CHAPTER VIII SETBACKS COLD and snow, however exhilarating and beautiful, cannot last forever; and it is well they cannot, for toward the end of February, when the sun begins to run higher and rise earlier, one feels a strange longing for a breath of the spring, for a smell of the moist earth. But March comes, frequently with deceptive mildness, when the streets run rivers of muddy water, the snow turns dull and dingy, the earth appears in sheltered, sunny places on the banking, the English sparrows fight and chatter and shriek in the naked trees, and in the evening the drip, drip, drip of water from the eaves lulls one to rest with dreams of spring. But in the morning what a change has taken place! A bitter wind roars like a lion in the trees, the air seems full of needles, the sun shines brightly, but does not warm. Not a sparrow is in sight. Huddled behind blinds and shutters and whatever serves as a shelter from the searching wind, they puff themselves into balls of feathers, and wait for warmer weather. "Ac venti, velut agmine facto,Qua data porta ruunt et terras turbine perflant." Again a few days of mild and sunny forenoons and a chill creeping into the air in the afternoon, with thin needles of ice threading the little pools of water in the road, followed the next day by a heavy snow-storm which changes into rain and sleet. But one day, and I never forget that day, a clear liquid warble is heard in the air, a wandering disembodied voice, the first spring song of the bluebird. I am thrilled and look everywhere, but in vain. I hear the clear notes but cannot see the musician, until all at once he alights on a fence-post, or on the roof of a shed, and warbles his flute-like tones. And one warm Sunday a few days later I walk into the garden. The soil is drying a bit in the higher places, but is soft and muddy in the hollows. The sun shines warmly, a Sabbath stillness is over everything. The hens prate cheerfully, a cow tethered in the sun in front of a neighbor's barn lows comfortably, the shrill call of a robin is heard, and spring really seems here. The first duty of an experienced gardener is to make hotbeds and therein cultivate beets, turnips, cabbage, cauliflower, lettuce, tomatoes, and other vegetables. So I sent for some planks, sawed them the right lengths, and spent a part of several days and the whole of several evenings in the furnace-room of the cellar, pounding and hammering the parts together and screwing on glass covers with hinges. I made three of these beds, and having arranged suitable sites for them on the south side of the barn, secured Mike as chief motive-power, and started to hoist them out. Then it was that I found the cellar door was several inches too narrow to allow them to pass through, whichever way I turned them. So I was forced to take them apart and reunite their component parts on the outside. This took so much time that it was not until two days later that I had them in place. I had been told that greenhouse or conservatory compost would make excellent growing soil, and so I imported a few loads at considerable expense from a neighboring florist, procured seed, and sowed, as I was afterwards informed, enough seed to furnish a market-garden of an hundred acres. It was a most delightful pastime, and in an astonishingly short time the tiny garden-shoots of thousands of young plants were peeping above the soil. It was delightful to see how warm and comfortable it was inside that frame. Indeed, it was necessary to raise the tops during the sunny days, to avoid burning the plants. And I could almost see them grow from hour to hour. For about ten days I guarded them as carefully as one would tend a new-born babe, and was rewarded tenfold by the astonishing progress the plants made. One warm sunshiny day I opened the windows about halfway. Toward night a warm, moist south wind began blowing, and before dark a fine, almost summer-like rain was falling, just the thing the plants needed. So I opened the covers wider, that the plants might get the benefit of the rain without the danger of a heavy drenching fall, which might wash them out of the ground. The next morning I found that the unexpected had happened. The wind had veered around to the northeast, it had become bitterly cold, a biting northeaster was blowing, and my plants were frozen stiff. It was a week before the ground thawed enough to plant more seeds; but I persevered, and, in about ten days after planting, had a second crop growing finely. I had also improved my time and had engaged a farmer with a yoke of oxen to plough my land. I had considerable difficulty in getting a yoke of oxen, because that useful animal, the ox, was an exceedingly rare bird in our vicinity. But I always wanted my farm ploughed by oxen, and I persevered until I found a yoke. It was somewhat more expensive than the quicker method of ploughing with horses, but I preferred oxen. And so, when they arrived, I persuaded the farmer to allow me to drive. How often had I admired the skill shown by the wielders of the goad in managing their unwieldy charges. Some of those old-time farmers were exceedingly graceful in using the goad. How easily they would slide it across the shoulders of the near ox and prod the off ox into activity. So I fain would do; and when, after setting the plough, the horny-handed yeoman grasped the handles and signaled me to go ahead, I poised the goad, made certain circular motions with it in the air, and in deference to time-honored but obsolete custom, vociferated, "Hubbuck thar, huggolden, hibboad, whoa, heish"; and they settled into the yoke, and mellow sounds of rending earth followed. This was delightful, and at the end of the furrow I turned them under his instructions, and started again across the field. Now I noticed that the off ox was shirking and allowing his mate to do most of the pulling, and to bring him up even I slid the goad across the near ox's shoulder, leaned my weight on it, and jabbed him powerfully with the brad, at the same time letting out a hoarse "Haw!" that waked the echoes. I have never known a draught animal to respond so quickly to encouragement as did this one, for the moment he felt the brad he bellowed loudly, stiffened his tail, and broke into a lumbering gallop, dragging his mate, the plough, and the ploughman in his wake. The plough, caught by the nose, turned over, the ploughman, clinging to the handles like a drowning man to a straw, shot into the air like a catapult, turning a complete somersault, while the oxen, racing across the fields, brought up one on each side of an oak tree, which stopped their mad flight. The yeoman showed more irritation over the affair than I thought its importance warranted, and said things that were calculated to pain one's finer feelings. Indeed, he absolutely refused to continue his engagement under any terms whatever, and to my great regret departed without even saying good-by. And I had so wanted to learn to drive oxen! And now I might never get another chance. It was too bad.  Shot into the air like a catapult |