| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

IV

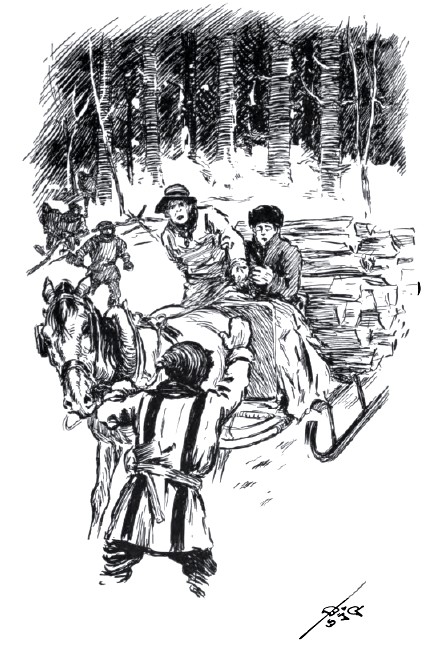

THE GALLIC WAR THE next morning I was at the henhouse before I took care of the horses. It was a sharp morning, with overcast sky, and the fowls looked a trifle hunchy. However, some dry grain scattered among the litter on the floor of their pens set them scratching actively, and as they scratched and warmed to their work they began to prate cheerfully, while the two cocks paraded up and down in front of their wire partition, defying each other, and saying doubtless all manner of evil things of each other. As I watched them swell and strut and lower their heads defiantly, and occasionally make a short rush at each other, a vague shadow of the old feeling that used to induce me when a boy to toss our rooster over a neighbor's fence, and then watch the battle that would ensue, came over me, and for a moment I felt a sinful desire to let them together for just a few jumps. The Hamburg was a handsome, silvery fellow, with long sickle feathers and well-developed spurs, while the Dominique was solid and chunky, with the well-marked hawk plumage that glowed with health. However, I refrained, and after watching them until breakfast-time, I went in without having fed and watered Polly and our well-bred brood-mare, which welcomed me after breakfast with reproachful nickerings and pricked-up ears. That noon, to my great delight, I found three fresh eggs in the nests, which I conveyed triumphantly into the house, dropping one on the floor, however, in my eagerness to show them to my wife, and induce her to retract certain opinions she had expressed to the effect that I would never get a single egg from my old hens as long as I lived. I might say in passing that that egg was somewhat more than ruined for life. The painstaking . endeavors I made to scrape it up with a spoon added nothing to its value or sphere of usefulness. But never mind, I had at least received some financial return for my outlay. Eggs were worth forty-two cents a dozen. That afternoon the long delayed snow-storm came, and before morning nearly a foot had fallen. I was out betimes with shovel and plough, and it was a pleasure to sit on the plough and drive while my son wielded the shovel. Exercise is a good thing for the young, and one of the greatest pleasures I experience is to sit and see others work. The air was brisk and full of oxygen, the snow was dazzling in the bright sunshine, the jolly tinkle of the sleigh-bells filled the air, while a flock of juncos sported in the tall dry weeds and grasses that in the fence-corners barely showed their drooping heads above their white mantle. I felt the beauty of the country and country life as never before, and how petty seemed my disappointments in life, in the great peace that seemed to spread over the face of Nature! As I went down to the office that morning, leaving my stock warm and well fed and my modest farm half buried in fleecy clouds of snow, I thought how much of life and beauty is now hidden safe and warm under Nature's blankets, only awaiting that magic summons to spring up into active and beneficent fruition. All that day sleighs dashed about town, and wood-sleds drawn by single teams, pairs, and fours thronged the streets. The farmers had been waiting for the snow. This set me thinking. What cleaner, better, fresher farm-work could there be than chopping in the winter woods. That's it! I would do it. Business was not very brisk in the office, and if it were, there was no particular need of a man being a slave to his profession. I had known instances of men actually drying up in my profession, and being, as far as real usefulness is concerned, "Like thin ghosts or disembodied creatures." The one thing I needed to develop a real homelike, woodsy, farmer-like feeling was to get into the woods, and load wood, and smell the delicious fragrance of the pines and the balsam of the freshly cut trunks. That afternoon I borrowed a single-horse sled of Daniel, equipped with a work-harness and chain-traces, arranged with him for a load or two of cord-wood piled in a distant wood-lot, and started with a Hibernian friend for the lot, to pluck and garner it for myself. Arrived at the lot, I let down the bars and drove along a rough lumber-road, through another pair of bars, down a hemlock-shaded path, where the heavily laden branches dipped and showered us with feathery masses. Then across a small bridge spanning a frozen, snow-covered brook, until I came to a cleared lot dotted with piles of neatly corded wood. In the distance we could see the smoke of a shanty fire, and hear the songs of Canadian wood-choppers, "Habitants of story," and the ring and thud of their axes. "Jolly, happy fellows," I thought, "true, care-free sons of the woods, without sordid thoughts, without disturbing and unhappy ambitions destined never to be rewarded. They indeed have the true secret of happiness. Enough to eat, enough to wear, health, the fresh air laden with balsamic fragrance, never a thought of money. Jolly, happy fellows, they are to be envied." And so, intent on such thought, I sprang lightly from our sled, donned my leather mittens, and vied with Pat in loading cord-wood. True, I did not successfully vie with him, because that seasoned veteran loaded by far the greater part of it; but I, in a measure, superintended the job and occasionally landed a stick on the sled. We took good measure, Pat saw to that, and when we started we were obliged to pry the runners out of the ruts where they had frozen. Lady M. pulled grandly, and we were smoothly sailing across the lot on the down-grade, when we heard loud shouting in our rear, and turned to see a picturesque figure in blanket-coat, moccasins, and toque, wildly waving its hands and shouting a jumbled and somewhat incoherent mixture of French and English, from which we gathered that he had some suspicions of the honesty of our intentions. "Voleur, arrêtez-vous you have ma hwood volé; par la Sainte Vierge, you have steal ma hwood, 'cré Baptême, bagosh, seh!" Rushing frantically to the horse's head, he grasped the reins, as if to prevent our escape, whereupon Pat tumbled off the load, spitting on his hands and exclaiming, "Dom the moonkey, lave me poonch th' Dago hid off him, whirroo!" And he jumped two feet in the air and cracked his heels together. I violently restrained Pat and ordered him on the load, which was good generalship on my part, as, from the neighboring lot, twenty excited compatriots of the first gaudy brigand came piling over the fence, and surrounded us amid a torrent of Gallic expletives. "For the love of hivin, yer 'anner," pleaded Pat, "lave me lick the twinty of thim, lave me land one poonch on the dhirty moog of ould Plaid Belly"; by which appropriate title he designated the premier brigand. "Keep quiet, Pat," I remonstrated, "this is a case for arbitration." "Arbitration be dommed," growled Pat, "wan good belt in th' gob of ould Plaid Belly wud do th' job aisy." However, I refused Pat's modest request, and raising my hand impressively, addressed the leader in our best Exeter Cotton Mill French. "Messieurs, qu'avez vous m'en voudre; Ich weiss nicht was zie meinen, dites-moi, pour l'amour de Dieu. What is it that it is?" Now this was so plain that even Pat was heard to mutter, "Begob, he can talk Dago talk awl right."  You have steal ma hwood! "Vous êtes un scélérat, vous have steal ma hwood, mille tonneurs; sacré', bagosh, me!" he shouted. "'Cré Bapture, bagosh," responded the chorus of voyageurs, "mille tonneurs." "Jist wan poonch, yer 'anner," pleaded Pat. "Shut up, Pat, I will run this affair without any fighting," I replied. "Pardon, messieurs, vous avez fait un faux pas. J'ai verkaup die bois von Herr Gilman, a qui appartient tous les bois herein." "Il n'appartient a M'sieu Gilman, il appartient a moi. I have it buy of M'sieu Gilman, me!" he shouted, waving his arms. "Oui, oui, bagosh, c'est vrai," responded the chorus. "Oh, wirra, wirra, 't would be aisy," murmured Pat. "Monsieur," I continued, courteously, "parlez un peu plus lentement, un peu langsam. La conversation rapide nicht mir gefallt." "Bien, m'sieu," he responded more affably, apparently soothed by my lingual attainments, "I have buy the hwood of M'sieu Gilman. J'ai coupe le bois pour lui, et it m'a payé de l'argent, il m'a vendu le bois detaché, for one hunner twonny-fav dollar, bagosh, seh, n'est ce pas?" "Bagosh, seh," echoed the chorus. "Ich verstehe parfaitement," I replied. "Je vous paierai pour les boil, si vous voulez," I continued gracefully. Thereupon smiles beamed on Gallic faces and peace seemed imminent, much to the disgust of Pat, who yearned for war. "Bien, m'sieu," said the other, "eef m'sieu me giv fav dollar, m'sieu can eet have." "Th' robber! lave me —" began Pat. "Pat," I interrupted, "we have been trespassing, and it is only fair that we should compensate this gentleman for the annoyance we have caused. We should be the first to recognize the justice of his claim, and do what we can to foster in these adopted citizens a respect for the law, that you and I as American citizens have." "Hill and blazes!" scoffed Pat, "wan good poonch wud tach thim dommed canucks more rispict than fhorty laws, and lave me give 'im jist wan for loock." But I refused, and handing a five-dollar bill to our friend, I gathered up the reins and drove off, not before we heard our "care-free sons of the woods, without sordid thoughts, without disturbing and unhappy ambitions destined never to be rewarded," remark to one another: — "Nom de Dieu, il a payé enormement; quel fou! he-he-he 'cré Baptême." And that night when we called on Daniel and related our experience, that guileful individual nearly had a seizure from convulsions of sinful mirth. But seriously, was that a Christian way of treating a man and a brother? |