| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

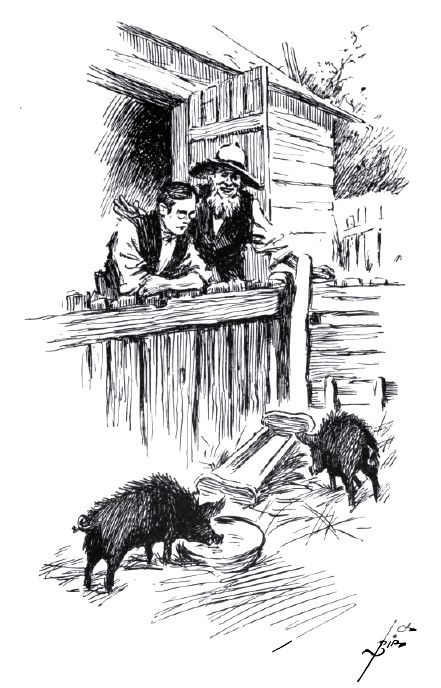

| CHAPTER II

I BUY MY PIGS I PASS over as uninteresting to my readers the details of house-repairing, the purchase of suitable furniture, new rugs, and other articles declared necessary by my wife. I also pass over many pungent remarks and spicy declarations of that frank lady in relation to my ability as a farmer, and my utility in general, although these remarks certainly would be vastly interesting and entertaining. During the interval that preceded my final removal to my farm, I ran up every day or two and viewed my two-and-one-half acres, inspected my barn and henhouse, and laid plans hugely. The arrival of the frigid season, of course, made any active cultivation of the soil impossible. I had heard of winter wheat, and had opined that I would sow a little for spring consumption, but before the formalities necessary to the transfer of the property, and the negotiation of the mortgage before mentioned, were finished, the ground had frozen so hard that the proper trituration of the earth was entirely out of the question, except by the use of high explosives, and I was far too modest to try any such innovation as dynamitic ploughing. So I would fain content myself with raising a few pigs and hens until the gladsome spring was at hand. I had really set my heart on pigs. Pigs were so comfortable, so good-natured, and so delightfully lazy. I respected and admired that trait. I was lazy, and had my circumstances in life permitted full indulgence in that most amiable of virtues, I would undoubtedly have done little more than to eat, sleep, and cultivate my mind by omnivorous but light reading. But unfortunately my financial state had been such that I was, and had been from the time when I burst upon a large and unappreciative community as a sort of reincarnated chrysalis attorney-at-law, compelled to spend a large part of my waking hours in that sort of practice which is commonly spoken of as active; why active, I cannot say. Consequently, not being able to give free rein to my slothful yearnings, I could respect and envy its possession in pigs, and pigs I was determined to have. Now my wife objected strongly to pigs, and when informed of my intentions, delivered quite a masterly argument on the subject. I was informed that pigs were filthy, nasty animals, always kept in abominably smelling pens, fed upon refuse, and breeders of typhoid fever, malaria, cholera, and other kindred evils. I assured her that while this was perhaps frequently so, these characteristics were not indigenous to the pigs, but were the results of improper food and unsuitable sanitary arrangements so painfully evident in the ordinary pig-pens, but that I intended to violate all the traditions of country pig-culture, by the development of specimens in a condition of perfect cleanliness, suitably nourished with the most approved foods. She replied that, while this was all very well in theory, I was the very last person in the world to keep up my interest in anything for any considerable period, and cited a long and painful list of instances in which certain theories of mine had been dissipated and thoroughly exploded, and at considerable expense to me. I waived the citations, however, and reminded her that the one common ground of neighborly good feeling in a bucolic community was the pigpen, and that more comfort was obtained of a Sabbath morning, and of a holiday, in leaning over the pig-pen with a neighbor, smoking and exchanging pastoral gossip, than in any other way. She retorted that I would be in much better business attending church on the Sabbath, and occasionally spending part of a holiday in beating a few rugs or mowing the lawn, instead of paying out money for what I could do perfectly well myself, if I only had a little energy. Goodness knew she needed the money badly enough for things in the house. Well, there was little use in continuing the discussion, and so I said no more at the time, but spent the greater part of my leisure hours during the week in building a good stout sleeping-floor in the pig-house, and wheeling in straw, ashes, and dry leaves. I was determined to have pigs. The next thing was to purchase my pigs. I was somewhat at a loss to make a choice of the comparative merits of Chester White, Poland China, Berkshire, Sussex, Bedford or Jersey Red. All these breeds and many others I had read of in my encyclopedia, but strange to say I could find no mention of the breed known as Runts. I had certainly heard somewhere of Runt pigs, and meant if possible to have some. I had many years before kept fancy pigeons, and knew that the variety known as Runts were the "giants of the pigeon tribe," and their squabs were the quickest growing, fattest, largest, and most delicious eating of any. The name Runt could therefore be applied to the porcine race for no other purpose, surely, than to indicate the possession of some remarkable qualities. Accordingly I decided upon Runts, if I could find any, and one evening I went across the way to consult my neighbor Daniel. Now Daniel, my nearest neighbor, is a gentleman of wealth and position, a lover of horses, an expert judge of cattle, and a famous breeder of swine. Daniel loves a trade in any one of the lines mentioned, and enlivens each exchange with so many quips and jokes and good stories, that, before you are aware, you have made the trade, taking in exchange for your horse or cow or pig a stock of new stories and whatever Daniel may have seen fit to unload upon you. I believe in perfect frankness whenever I try to trade with a man, or to buy of him anything I know but little of. And so when I told Daniel I wished to buy a pair of his best pigs and would leave the price to his fairness, I knew I should be treated as a man and a brother. "Now, Daniel," I said, "I don't know anything about pigs, and you do, but I have some decided ideas in the matter. I have thought over the different breeds, and have decided to get the best, even if they do cost a trifle more. I want a good pair of Runts, and I don't know just where I can get any." "What do you want Runts for?" said Daniel, with an expression of astonishment on his ruddy face. "Well, I suppose it will be a bit expensive," I replied, "but if a man is going to be a farmer, even an amateur farmer, he might as well do the thing right, and unless you begin right you won't go very far. Now, a few years ago," I continued, "I went in a bit for fancy pigeons and squab-raising, and although I didn't make any money on the venture, I picked up a lot of information. And let me tell you this, Daniel, Runts are the largest, quickest-growing, and easiest to fatten of any breed of pigeons, and I believe there is good money in Runt pigs." Daniel threw back his head and laughed loudly, then leaning forward, with a shrewd twinkle in his eye, he said: — "Well, old man, you are more of a farmer than I thought. Now if you are determined to have Runts I will tell you something. I didn't intend to let any one know, but I have a pair of Runts, beauties too, that I will let you have. They come a bit high, because, as I suppose you know, a Runt pig is not nearly as common as other breeds of pigs. You can have a pair of any of my other pigs for twelve dollars, but for the Runts I shall have to charge you eighteen." "Well, Daniel," I replied cheerfully, "if that is the best you can do, here is your money"; and I handed him the money. "Well, hold on," he cried; "don't you want to see the pigs before you buy them? How do you know I will give you what you have paid for?" "Oh, you will treat me all right. I want Runts, and you have Runts, and I want the best pair you have." "All right," said Daniel, somewhat doubtfully, as he tucked the bills into his vest-pocket, "you shall have them to-morrow, only I don't want any kick coming." "There will be no kick coming, Daniel; this is a fair bargain, and as long as I get Runts I shall be satisfied. Only understand, don't palm off on me any ordinary pigs, — just plain Runts and nothing else." "All right, my son," said Daniel, coughing so violently into his handkerchief that he had to wipe his eyes. The next noon when I returned from the office to lunch the pigs had arrived, and our entire family, barring my wife, was leaning over the pen contemplating them with awe. And, indeed, at first sight our inexperienced eyes could detect the fact that they were no ordinary pigs. They were small, much smaller than I supposed, and were covered with a most astonishing growth of hair, and their teeth or tusks seemed considerably in advance of their general bodily development. They stood with their front feet wide apart, and were somewhat wabbly on their hind-legs. Indeed, their progress about their pen resembled that of an inebriated gentleman endeavoring to navigate an uneven sidewalk. But I recollected that the young of Runt pigeons were delicate until they approached maturity. Still, even with these reflections, I did not feel entirely satisfied with my bargain. After lunch I repaired to the pen, and in the presence of my children administered a proper amount of nutriment to my stock, which, however, did not manifest much enthusiasm for their food, a lack of appreciation of our efforts in their behalf which was unquestionably the result of unfamiliarity with their surroundings. The next morning was Sunday, and, true to my prophecy, neighbors began to stroll in after breakfast to examine my stock. "Great Moses!" exclaimed the first man the moment his eyes rested on the animals, "who sold you those Runts?" "Well, never mind where I got them," I replied shrewdly; "it isn't every one who can get a fine pair of Runts. They came a bit high, but I was bound to have them." For a moment he eyed me with amazement at my reticence, and then burst into a roar of laughter and clapped me on the back, swearing that I was a sure enough farmer. Indeed, most of my callers that day seemed so unusually cheerful that I began to be a bit suspicious. The physical condition of my pets occasioned me some uneasiness, and the recommendations of my friends as to medical treatment were to the last degree discouraging. One recommended charcoal and bone-meal. Another, the amputation of the tail. Another, to slit the forehead and rub in sulphur. Still another, to look for black teeth and pull them. That night the smallest pig died, and was buried with suitable ceremonies and after titanic exertions with a pickaxe. That afternoon I had stolen an hour from office-work and fared to the library, where I consulted various works on Domestic Swine. After an exhaustive search I found the following: — "Occasionally there will appear in a litter of pigs a stunted, dwarfed, or misshapen one, known as a runt. Whether this is a harking back to the original type or a direct inheritance from some defective but more recent ancestor matters little. The runt is of no value whatever, and should be killed at birth. Indeed, by allowing him to remain with the others one may menace the well-being of the healthy pigs, inasmuch as the runt is much more liable to contract disease than its healthy congeners. We have yet to hear of a single instance in which a runt ever developed into a healthy pig."  Swearing that I was a sure enough farmer After reading this oracular essay, I reflected a bit. Daniel had done me. No, that was not quite fair to Daniel. I had done myself, and Daniel was the highly amused medium by which I had been done. Well, I had paid eighteen dollars for a bit of experience, and it might be of that value in the end, but just at that moment it appeared a rather high price. But then, think of the vast amusement my friends had received and the general rejoicing of the public over the joke. At the thought of this I grew hot and cold by turns. I soon decided on a plan of action. That night, under cover of darkness, I drove to a neighboring town with my son, and bought a couple of fine, healthy pigs, for which I paid the modest price of eight dollars, leaving the sole surviving runt with the farmer, who promised to put him out of the way. And so, the next day, when jovial friends called to view my runts, they expressed much astonishment at the unreliability of gossip, and each and every one appeared much discomfited and cast down. Now the new pigs throve bravely and ate ravenously. True, they squealed raucously when they did not get their food at the regular periods, but they seemed to grow perceptibly from one day to another, and little by little I began to regain my assurance and to talk a bit. But, alas for my confidence, I had not yet seen the last of my trouble as a porciculturist, for one morning the three members of the Board of Health stalked into my office and sat down ponderously. "Squire;' said one, after portentously clearing his throat, ".be ye aware that ye air a-vilatin' the regilation of the Board of Health in keepin' pigs?" I was astounded, and gaped at the three gentlemen with open mouth. "Why, heavens and earth, gentlemen, can't a man keep pigs in a country town on a three-acre piece, when they are kept as clean as fresh straw and dry beds can make them?" I shouted in astonishment. "No, squire, they can't, s' long 's we're on the Board," he stoutly affirmed; "and what's more," he continued, "I'm .s'prised 'at you sh'd try teat dew it, squire, when you know the law." "Has any complaint been made?" I queried. "No complaint's been made by nobody," replied the chairman. "Have you examined the premises?" I asked again. "Yes, squire, we've looked 'em over keerful, an' we're bound to say ye've kep' 'em neat 'n' tidy 's a barn-loft, but that don't make any differ, ye can't keep pigs in the compact part of the taown, leastwise not 's long es we fellers is on the Board." "Why, damn it all, gentlemen, do you' seriously mean to forbid me from keeping pigs by calling up a law that is only made to regulate abuses, like the five-miles-an-hour law, and fifty other such laws that I could name?" I demanded, with pardonable heat, but highly questionable emphasis. "That 's the law, squire, and this is the abuse it's made to regilate, an' we're here to regilate it. Naow what yer goin' tew dew 'baout it?" I reflected a moment. They were right, such was the law, and I certainly ought to be the first to recognize their right to enforce it, although it was an extreme view to take of it, and sorely disappointing after my earnest and well-meant efforts to benefit and improve the art of keeping pigs. "Well, gentlemen," I replied at length, "I consider that you are taking an extreme view of the law, but I shall yield. The pigs will go tonight, that is, if you gentlemen will be good enough to give me until then to get rid of them." "All right, squire," replied the chairman cheerfully. "Ye can have 'til to-morrer mawnin', and if ye'll sell 'em right, I'll buy 'em," he continued, eyeing me with a business air. "You haven't money enough to buy them, sir," I replied with dignity, and they clumped heavily down the stairs. That night the pigs were returned to the farmer at the same price which I gave for them, although they were nearly a third larger; and so, although my love for pigs was in a sense betrayed, "'T were better to have loved and lostThan never to have loved at all." |