| |

(HOME)

|

|

FALMOUTH

NECK IN THE REVOLUTION. 1

"ONE OF THOSE OLD TOWNS — WITH A HISTORY." BY NATHAN GOOLD. IN 1632, when John Winter ejected George Cleeves and Richard Tucker from their settlement at Spurwink, forcing them to settle on the then unoccupied and unclaimed peninsula afterwards called Falmouth Neck, now Portland, he little thought that they were to be the founders of a city. This pleasant town has not come to its present state without much heroic sacrifice, both in blood and treasure, by its inhabitants. Here, in 1676, the settlers were attacked and thirty-two were killed and carried away by the savages. The rest of the inhabitants fled to Cushing's Island, with Rev. George Burroughs, and it was not until 1678 that they returned and built for further protection Fort Loyal, near where the first settlement was made. In October, 1689, Col. Benjamin Church, with about eighty men, had a fight with several hundred Indians on Brackett's, now the Deering, farm and lost twenty-one men. This battle, it has been said, saved Maine to the United States. In May, 1690, for five days and four nights, the garrison of Fort Loyal, under the command of the brave Capt. Sylvanus Davis, kept at bay between four and five hundred French and Indians. The first night when they were ordered to surrender the garrison they answered, "that they should defend themselves to the death;" but they were finally compelled to submit to their treacherous enemies, who carried a few to Canada and cruelly murdered nearly two hundred, whose dead bodies lay exposed to the wild beasts and birds and the bleaching storms for two years, when Sir William Phips and Col. Benjamin Church, on their way to Pemaquid, buried them, probably near the foot of India Street, and carried away the eighteen pounders from the fort. Every house was burned and what had been a settlement remained a wilderness for nearly twenty-five years. Then the settlers came again; but the story of the town through the following French and Indian wars, to our troubles with the mother country, is not one of peace, but they were years of anxiety to the inhabitants. In the earliest times Massachusetts was cruelly indifferent to the safety of the poor settlers of Falmouth Neck and wilfully neglected them. Near where the first settlement was made, not far from the foot of Hancock Street, is our most historic locality, but now the visitor goes there only to see the place where the poet Longfellow was born, and the house where the man first saw the light of day who taught the National House of Representatives that their first duty was to learn to govern themselves. Falmouth Neck, at the commencement of the Revolutionary war, had less than nineteen hundred inhabitants, and they occupied only the territory bounded by Congress, Center, Fore and India Streets, with a few who lived on Fore Street outside those limits. There were about two hundred and thirty dwellings and there was no street northwest of Congress, which was then called Back or Queen Street, to Center, and west of that it was Main Street or "the highway leading into town." All between Congress Street and Back Cove was woods. Middle and Fore Streets were the only long streets that ran in the same direction as Congress. Center was the last cross street up town and was called Love Lane. Temple Street was Meetinghouse Lane. Exchange Street was laid out only from Middle to Fore, and was called Fish Street. On the west side there were but two shops and one house, and on the ea st side there were three houses and one shop. Property on this street was of small value, as it was too far up town. There was a knoll where the post-office now stands. Market Street ran only from Middle to Congress and was called Lime Alley. Pearl Street from Middle to Congress was simply a lane, and on the south corner of this lane and Congress Street stood a windmill where was ground their corn, and part of the millstone is now in Lincoln Park. About what is now Pearl Street, but formerly was Willow Street, from Middle to Fore, was Pearson's Lane. Franklin from Congress to Fore Street, was called Fiddle Lane. Newbury Street extended only from India to Franklin, and was called Turkey Lane. The only part of Federal Street then used was a short lane from India Street southwest. Hampshire Street was a short lane from Congress, called Greele's Lane. A lane ran from Center to South Street, where Spring Street now is, "to Marjory's Spring." A short lane extended northwest from Middle Street, near where Exchange Street now is, but had no name to us known. Plum Street was Jones' Lane. India was the street of the town and was called King Street, but the name given it was "High King Street." On or near this street most of the business of the town was done. Thames Street extended from India, where Commercial now is, a short distance to Preble's wharf, or the ferry. On this street Jebediah Preble lived. Grove Street was laid out in 1727, but was simply the road out of town to the east and that name was not given it until 1858. On the water front there were about twelve short wharves and most of these were destroyed by Mowat. The Eastern Cemetery contains about seven acres, but in 1775 it was but about half as large as now. In the earliest times the settlers on the Neck began to bury their dead about the lone Norway pine on the side of the hill. That tree stood about six feet south of Parson Smith's monument and was blown down about 1815. The front part of the cemetery, on Congress Street, was the parade ground which afterwards was added to this "ancient field of graves." Here was located the pillory and whipping-post and at the eastern end was the pound. Soldiers were here whipped for misdemeanors during the Revolution. The yard now contains about seventy-five tombs and about five thousand graves. In the old part, probably not over one-half of the graves are marked at all. The tombs are in a good state of preservation and the oldest and largest is Joseph H. Ingraham's, built about 1795, which is said to contain over sixty bodies. The next one was built by Nathaniel Deering. This was the only public burial place until 1829, and a walk among those graves is to commune with the past. The memories of those people, who bravely met the responsibilities of their times, gives one courage to continue the battle of life. Here, no doubt, are buried over one hundred Revolutionary patriots, but many of their graves must he classed with the unknown. This cemetery is the most precious possession of Portland and is indeed "holy ground." South of the Eastern Cemetery was a swamp. Near the junction of Federal and Exchange Streets was a swamp and a pond, and between Market and Pearl Streets, below where Federal now is, was another pond, and from these ponds ran a brook of considerable size, down, near where Exchange Street is, crossed Fore Street, east of Exchange, where there was a stone bridge about fifteen feet wide. Clay Cove, at the foot of Hampshire Street, made up so that boats passed under an arched bridge on Middle Street to Newbury, where a brook entered the cove. At the head of Free Street was a swamp and for many years after, when people began to build that way, it was thought that that land would never be fit to build upon and was of little value. There was an orchard on the south corner of Temple and Congress Streets and one about where Cotton Street now is, besides Parson Smith's, Dr. Deane's, and the Brackett's. The tan-yard of Dea. William Cotton was at the foot of the street that was afterwards named for him. At the foot of Center Street was a brick-yard. Between South and Center Streets, southeast of Spring, was swampy ground. Free Street was laid out in 1772, but was not used until after the war because of the soft swampy condition of the soil. The new court-house, built in 1774, was fifty feet by thirty feet and stood on the west corner of Middle and India Streets. Here it was that the inhabitants met October 18, 1775, and refused to surrender their guns when Mowat burned the town. The old courthouse was moved to Greele's Lane in 1774 for a townhouse, where it was burned the next year. The custom-house, from which the stamps were taken in 1766, was on the south corner of Middle and India Streets, opposite the new court-house, and was a dwelling-house before it was used for that purpose. The First Parish church stood where the stone church now stands, side to the street with the steeple on the southwest end, but was then unpainted. The same vane is on the present church, and on the chandelier is a cannon hall fired by Mowat into the "Old Jerusalem," as this meeting-house was afterwards called. This old church was taken down in 1825. St. Paul's church stood where the west corner of Middle and Church Street now is. Parson Smith's house was opposite the head of India Street on Congress, and was built for him by the town in 1728. It was for many years the best in town and was the first house to have room paper which was fastened on with nails. In 1740, it was spoken of as "the papered room." It was a garrison house in 1734, and was the last house to burn in the destruction of the town in 1775. Parson Smith was short of stature, pretty full in person and erect, but had a feeble voice. He would have been a successful business man but cannot be called a zealous patriot, judging from the entries in his journal, although he no doubt wished for the success of the cause. He enlisted in May, 1781, his slave Romeo, in the army, for three years, giving him his liberty in consideration of one-half of his wages. Capt. Coulson, the Tory, lived on India Street, northeast side, a short distance below Federal Street. Next to the new courthouse on Middle Street, was an engine-house in which was a new fire-engine. The two hills were formerly covered with trees and bushes and Dr. Deane, to prevent the total destruction of the primitive forest, purchased the remaining standing trees on Munjoy and they were permitted to remain during his life, but soon after his death they fell prey to the avarice of man. A two story building in those times was sizable; a three story one was high and there were hut few in - town. Many of the buildings were unpainted and the general color of those that were was red, although a few were painted a light color. There was no bank or newspaper in town and a post-office was not established here until May, 1775, with Samuel Freeman as postmaster. Joseph Barnard was post-rider and the first arrival of the mail was June tenth. The number of letters mailed at this office in 1775 did not average five a week, and the postage to Boston was ten and one-half pence. The mails were sent but once a week and were very irregular. As late as 1790 it took a letter sixteen days to come from Philadelphia, thirteen from New York and three from Boston. At the beginning of the war the merchants were having a profitable trade with Great Britain, which may account for their hesitancy in the early months of 1775. This may give some idea of the extent and condition of Falmouth Neck at the opening of the Revolutionary war, but let us now draw nearer to the town and examine the buildings and localities that were connected with the struggle for our country's independence. It is said that there were three taverns on the Neck during the war, but a traveler could put up at the house of Moses Shattuck, the jailer, in Monument Square. Such entertainment seems to have been a custom of the times and probably added to the income of the jailer. In those taverns our forefathers met and resolved what they would and what they would not do. They were also places of good cheer and the resort of men of social tastes, who in those days did not hesitate at the flowing bowl. Here often fun went furious and the wags found plenty of opportunity for their wit. The taverns were Alice Greele's, Marston's and John Greenwood's. Alice Greele's tavern was a one story building, large on the ground and had six windows in the front, with the front door in the middle. The bar-room was the north room on the left of the front door. The house stood on the east corner of Congress and Hampshire Streets. In this house met the county convention of September 24, 1774, but the afternoon session was held in the town-house near by. Court was held here several times during the war, and in 1776 she charged for the room ten shillings and sixpence, and the next year two pounds and eight shillings. This tavern was the resort of the patriots of the town, where they met to hear the news and consult on the situation of affairs; but as a place of social meetings it is best known to us now. Willis says, "It was common for clubs and social parties to meet at the taverns in those days and Mrs. Greele's on Congress street was a place of fashionable resort for old and young wags, before as well as after the Revolution. It was the Eastcheap of Portland and was as famous for baked beans as the Boar's Head was for sack, although we would by no means compare honest Dame Greele with the more celebrated though less deserving hostess of Falstaff and Poins." Alice Greele saved her house during the bombardment in 1775, by remaining in it and extinguishing the flames when it caught fire. It is said that a hot shot landed in her back yard and fired the chips. She took it up in a pan and threw it into the lane and said to a man, then passing, "They will have to stop firing soon, for they have got out of bombs and are making new balls and can't wait for them to cool." The tavern was kept by her over thirty years. She died about 1795; her daughter Mary sold the house in 1802, and in 1846 it was cut in two, moved to Ingraham's Court, off of Washington Street, where it burned in 1866. About 1820, it was four respectable tenements and the house had no addition. Alice Greele's maiden name was Ross and she married in 1746 Thomas Greele, who died about 1758. They had, at least, two sons and two daughters. The sons, William and John, were no doubt soldiers. Marston's tavern was a two-storied, hipped-roof building, with dormer windows, and stood in Monument Square where the stores, numbers 7 and 9, occupied by George E. Thompson and Thomas L. Merrill, now stand. The building was originally of one story, but was probably altered to two stories by John Marston before the war. The stable and sheds are still standing in the rear. The tavern building was moved to State Street in 1834, and is now standing on the southwest side, near York Street, but the roof has been changed. When it was moved one of Mowat's shot was found in the chimney, which then stood in the center of the house. John Marston bought this tavern in 1762 of Robert Millions and his wife Mary, who was a daughter of Thomas Bolton of Windham. Marston was an inn-holder then, and kept this tavern until his death about 1770. He was succeeded by his wife Susannah, assisted probably by her son Brackett, until 1779, when he became the landlord, and in 1782, his brother Daniel succeeded him. Brackett Marston's children sold the tavern in 1795 to Caleb and Eunice (Bailey) Graffam. He was a soldier from Windham, and they had probably kept it sometime then as Columbian tavern. Caleb Graffam was a post-rider to Hallowell and Wiscasset, having commenced in 1791. He sold the tavern to Josiah Paine, also a soldier and post-rider, in 1810. Thomas Folsom kept it in 1812 and 1815, and the name remained the same. Then came Timothy Boston, after him, in 1823, Israel Waterhouse and the last landlord was Aspah Kendall, who kept it until 1834, when it was moved. This tavern's historical associations are with the year 1775, as it was to this house that Col. Samuel Thompson's company carried Capt. Mowat when he was captured on Munjoy Hill, in May, 1775; and it was here that Capt. Wentworth Stuart and his men carried the five men, the crew of Coulson's boat, who were captured by Capt. Samuel Noyes and his company, at the mouth of Presumpscot River, June twenty-second. Greenwood's tavern was built in 1774 by John Greenwood on the south corner of Middle and Silver Streets, but was not finished by him. The house was of three stories with brick ends, but with no windows in the ends. In its erection was one of the first attempts at using bricks in building the walls of a house on Falmouth Neck. Several times the soldiers were ordered to assemble at this tavern during the war, and in 1776 a court martial was held here. In 1783, Mr. Greenwood sold the house to Joseph Jewett who finished it, moved there and kept store in the lower eastern room. The building was taken down by Hon. John M. Wood, to make room for stores, about 1858. Besides Marston's tavern, there are now, at least, six houses that were standing in Portland, at the commencement of the Revolutionary war. Three of them have been moved from the sites they occupied at that time and all have been somewhat changed. These houses were Parson Deane's, John Cox's, Benjamin Larrabee, 3d's, Joshua Freeman's, Joseph McLellan's and Brice McLellan's. Dr. Deane's is now the Chadwick House, and was formerly located where the Farrington Block stands, hut back from the street. Dr. Deane came here in 1764, and was then thirty-one years of age. The Neck had about one hundred and fifty dwelling-houses, and a population of about one thousand. His salary was one hundred pounds. In 1765, he purchased the three acres of land for sixty pounds, and began the erection of this house. He purchased thirty-eight thousand bricks for the chimneys, raised the frame July eleventh, and paid Col. Preble thirty-four pounds for rum and oil. The next January he bought the paper for two rooms and the entry, which cost him forty pounds. He bought himself a chaise and paid one hundred and eighty pounds for that, and then there were but two others in town. He married April 3, 1766, Anne, daughter of Moses Pearson, Esq., who was about five years older than himself. In July, 1767, he put up lightning-rods. The house then was but two-storied with a four-sided roof of two pitches and a short ridgepole. There were three dormer windows in the front, and the house was painted a light color. Then, there was no building except the church to Wilmot Street, and none on that side of Congress until almost to Casco Street. In the rear of the house was a large orchard. When Mowat burned the town, a shot went through the front of the house and landed in the chimney. The hole in the panel over the fireplace was always covered by a picture and so remained while Dr. Deane lived. He moved three loads of his goods November 3, 1775, and left the house expecting the balance of the town would be destroyed by the man-of-war, Cerebus. The next day the company commanded by Capt. Joseph Pride occupied the house. Pride's Bridge was named for him. January 16, 1776, Dr. Deane rented at ten pounds per month, three rooms below and one above, with the barn, to James Sullivan, who was the commissary here at that time. Gen. Joseph Frye, who took command here November 25, 1775, also lived in this house. In the summer of 1776, Dr. Deane built himself a one-story, gambrel-roofed house at Gorham, which he called " Smith Green," and the farm he called "Pitchwood Hill." In 1780, he wrote a long poem called " Pitchwood Hill," which closes with these lines: — Hither

I'll turn my weary feet,

Indulging contemplation sweet, Seeking quiet, sought in vain In courts, and crowds of busy men; Subduing av'rice, pride and will, To fit me for a happier Hill.

Dr. Deane returned to town in 1782, and died in 1814, aged eighty-one years, it being in the fifty-first year of his ministry. The house was then occupied by Dr. Stephen Cummings and in 1817 was sold to Samuel Chadwick, who sold it to Isaac Lord in 1818, and he added the third story. In 1822, Samuel Chadwick bought it back and it was occupied by Dexter Dana as a first-class boarding-house, then in 1825 by Bradbury C. Atwood for the same purpose. About 1835, Samuel Chadwick, a son of the former owner, bought and remodeled the house and it was occupied by his family until 1866. Since that time it has not been used as a private residence. In 1876, it was removed to the rear where it now stands. John Cox's house stands on the west corner of High and York Streets, and was built by him about 1735. He was the first of the name here, and was killed by the Indians at Pemaquid Fort in 1747. This house with an acre of land was set off to his eldest son, Josiah, in 1755. It was much enlarged by his granddaughter, Mrs. Philip Crandall, who occupied it until 1814, when she and her husband moved to Windham. This is the next to the oldest house in Portland and for fifty years after it was built what is now High Street was a cow pasture. Capt. Richard Crockett owned and occupied this house about forty years and died there about 1880. The house of Benjamin Larrabee, 3d, is now past its usefulness as a dwelling. It stands in the rear of Machigonne engine-house, but formerly was located about ten feet from Congress Street as it now stands. It was moved back into Mr. Larrabee's garden to make room for the block. This house was built before 1755 and occupied by Benjamin Larrabee, the third of the name, who married Sarah, the daughter of Joshua Brackett. The latter formerly lived in a log house where Gray Street now is, hut at the time of the Revolution, about opposite the head of High Street. He died in 1794, aged ninety-three years. In 1755, Joshua and Anthony Brackett, brothers, owned all the land above about where Casco Street now is on Congress Street. The Bramhall lot of four hundred acres may not have been included in this. That land they inherited from their father Joshua, who was a son of Thomas and Mary (Mitton) Brackett, a granddaughter of George Cleaves. Thomas Brackett was killed by the Indians at Clark's Point, near where the gas house now is, in 1676, and his wife with three children was carried to Canada, where she died in the first year of her captivity. The same day, August eleventh, his brother Anthony was captured on the Deering Farm, with his wife Anne Mitton and five children; and her brother Nathaniel Mitton, while offering some resistance, was killed on the spot. Anthony Brackett and his family escaped to Black Point in an old canoe, which his wife mended with a needle and thread which she found in a cabin. Hon. Thomas B. Reed is a descendant of Thomas Brackett and through his wife Mary Mitton, also of George Cleaves, the first settler. Benjamin Larrabee, 3d, was born in 1735 and died in 1809. The Larrabee house was occupied as a dwelling until about 1890. This lot of land is owned by a descendant of George Cleaves from whom it descended. Joseph McLellan's house stood on Congress Street (numbers 516-518) nearly opposite Mechanics' Hall, and the one-story wing is now standing at number 106 Preble Street. The house was framed at Gorham in the fall of 1754 by Hugh McLellan and his son William, and erected on Congress Street in the spring of 1755. The other part of the house was of two stories and stood on the lot now numbered 516, and was taken down when the building now standing there was erected. Joseph McLellan married Mary, the daughter of Hugh McLellan of Gorham, in 175.6. His brother James married her sister Abigail the month before. Joseph died in this house July 5, 1820, aged 88 years, and was buried in the Eastern Cemetery, but there is no inscription to his memory. When the house was built, there was but one other house on that side of Congress Street to Stroudwater bridge which was built in 1734. Except where the woods intervened, there was an unobstructed view of the harbor, the islands and Back Cove. The house stood in the midst of a large garden and the wing was at right angles with the other part, front to the street, and had the same dormer windows as now. Through the center of this part was the main entrance to the house, and on the door was an ornamental brass knocker. About 1866, it was removed to Preble Street and is perfectly sound to-day. Joseph McLellan was the son of Brice McLellan, and he and his sons, Hugh and Stephen, were Revolutionary patriots and became prominent merchants of the town. He was one of the committee, commissary of the Bagaduce expedition and commanded a company in the service. His son Stephen built the "Jose House," and Hugh the "McLellan-Wingate House," on High and Spring Streets, both in the year 1800. At the latter house, in 1825, Gen. Lafayette paid his respects to the daughters of General Henry Knox and General Henry Dearborn. Joshua Freeman's house stands on the southwest side of Grove street, back from the street, and is better known as the Jeremiah Dow house. Joshua Freeman was a brother-in-law of Dr. Deane, both having married the daughters of Moses Pearson, Esq. Here Dr. Deane went when he left his house November 2, 1775. Mr. Freeman has left to us a description of a fashionably dressed young man of 1750, it being a description of himself when he went courting. He wore "a full bottomed wig, a cocked hat, scarlet coat and breeches, white vest and stockings, shoes with buckles and two watches, one on each side." He died there in 1796, aged about sixty-six years. His father was named Joshua, and before the war kept a tavern on the corner of Middle and Exchange Streets, and was known as "Fat Freeman" for his size. He died in 1770, aged seventy years. Brice McLellan's house is the oldest in town and was probably built before 1733. The brick basement has since been added. It originally was a small one-story house near the shore, and stood where it now stands on York Street, near High (number 97). In this house Brice McLellan, the first of the name here, lived and reared a family who have played well their part in our town. He was an Irish Presbyterian, a weaver by trade, and came over about 1730. His sons were Alexander, Joseph, James, and William. Alexander lived at Cape Elizabeth; Joseph and William at Falmouth Neck; and James married Abigail McLellan, a daughter of Hugh of Gorham, where they lived and had ten children. William lived on Middle Street, present number 235. He was one of the committee in the Revolution, and was in command of the transport sloop Centurion, that carried Capt. Peter Warren's Falmouth Neck company to Bagaduce in 1779. He was the grandfather of Capt. Jacob McLellan, who as the war mayor of the city sustained the reputation of his ancestors. Col. Clark S. Edwards, of the Fifth Maine Regiment, is a grandson of James and Abigail McLellan of Gorham, therefore a great-grandson of both Brice and Hugh, the first of the name here. Concerning the forts of the Revolution on Falmouth Neck, hut little has been written because there has been but little of their history preserved. In the summer of 1776, at least ten cannon were sent here from Boston, but it was ordered that only those be sent that had one or both trunions broken off. Forty rounds of ammunition were ordered for each cannon. In September, it was ordered to supply Falmouth with fifteen hundred pounds of powder, twenty 32-pound, twenty 18-pound, one hundred and fifty-two 12-pound, one hundred and fifty-four 9-pound and one hundred and two 6-pound cannon balls, which shows the caliber of the guns mounted here. The fortifications were known as the Upper Battery, the Lower Battery, the Great Fort on the Hill, the Magazine Battery and Fort Hancock on the present site of Fort Preble. The Upper Battery was located on Free Street on the hill where the Anderson houses now stand and extended to the next lot. This is said to have been the location of a garrison house before 1690. The Upper Battery was probably built in 1776, and that year at one time Benjamin Miller was in charge with ten men. It is not known whether there were more than two guns mounted here, but of those one was a 32-pounder. probably soon after the war Nathaniel Deering built a windmill on this hill and when Free Street was laid out it was called Windmill Street for a long time. Willis says the windmill was finally moved over the ice to the Ilsley Farm, at Back Cove. The Anderson houses were built in 1803 by Jonathan Stevens and Thomas Hovey, who came from Gorham. The original part of the Orphan Asylum was built by Ralph Cross in 1791. The Lower Battery was on the rocky bluff, about fifteen feet above high-water mark, at the foot of Hancock Street, which was the site of Fort Loyal. The fort lot is said to have comprised about half an acre of land. When the Grand Trunk Railway was built the bluff was leveled off, and probably a part of the depot and the engine-house stand on the fort lot. Here, at this battery, was built a platform and there were mounted, at least, one 18-pound and three or four 12-pound guns, perhaps more. Moses Fowler was chief gunner at one time in 1776, and had fifteen men. The main guard here, in September, 1776, consisted of one commissioned officer, one sergeant, one corporal, and twenty privates. They were relieved every twenty-four hours at eight o'clock in the morning and were required to place a sentinel in each of the other forts. The old guard-room of Fort Loyal was still standing near the fort where the men were quartered. In September, 1776, Capt. Abner Lowell kept a sergeant's guard here, whose duty was to have one sentinel on the platform day and night to hail vessels coming into the harbor and going out, and no vessel was allowed to pass this battery without a pass signed by order of the committee of the town. At this fort was probably raised the first American flag on Falmouth Neck, July 18, 1778, which the guard saluted with a 12-pounder. At sometime during the war a battery may have been built where Fort Sumner Park now is on North Street to defend the approach from Back Cove, as it is stated that there was an old earthen breastwork there in 1795, when they were building Fort Sumner. The "Great Fort on the Hill," as it was called, was probably on the brow of Munjoy Hill, about where Fort Allen Park now is, and the earthworks there may have been a part of it. Willis and Goold both located it there, although there seems to be no positive evidence of its location now. That seems to be the most reasonable place considering the short range of the guns at that time. This was probably a long earthwork extending around that corner of the hill; but from the orders, the indications are that either it never was completed or that it was not then considered an important fortification, except in case of an attack from that quarter. The fort was probably begun in November, 1775, when the people were alarmed by the Cerebus, and here it was that the people worked all that Sunday, the fourth, as Parson Deane says, "all the people at work to-day and there could be no meeting." They mounted two 6-pounders, which alarmed Capt. Symons. The same location was used for a hospital for the twenty-six sick soldiers of Col. Winfield Scott's regiment who were captured at Queenstown in 1812, and were brought here the next December. More than half of these soldiers died, and they, with eight small-pox patients who died in 1824, are buried within the iron fence on the Eastern Promenade, north of Congress Street. The Magazine Battery, was in Monument Square and mounted five guns, probably small caliber. This battery was under the charge of an officer and ten men. The guns in all the batteries were "exercised" every day and provided with six rounds of ammunition. The magazine was the jail, erected in 1769, which was eighteen feet by thirty-eight feet, built of hemlock timber twelve inches thick, lined on the inside, top, bottom and sides with iron bars and planked over the bars. It had a chimney in the middle. There were two windows for each room and chamber, with nine panes of seven by nine glass, properly grated. There was but one outside door. In 1776, one side was used for the magazine and the other for the prisoners. Wheeler Riggs had charge of the magazine and battery. He was a carpenter, and was the only man from Falmouth killed at Bagaduce, in 1779. He was stooping over, fixing a gun-carriage, when a cannon ball hit a tree near, glanced and struck him on the back of his neck. He was married and lived on Plum Street. The jailer's house was near the jail. Nearly in front of where the Soldier's Monument now stands, was the hay-scale, which the town had purchased for twenty-seven pounds. In the time of the war, there were no houses on the northwest side of Congress Street in this square, also no Elm, Preble or Federal Streets as now. There were a few buildings on the southeast side besides Marston's tavern. West of the square, Congress Street was simply a country road, leading out of town. The prominent events of the Revolution can be said to have begun on the Neck soon after the passage of the stamp act, for a mob marched to the customhouse, in January, 1766, and demanded the stamps, which were carried through the streets on a long pole to a bonfire, probably on the parade-ground, where they were burned in the presence of a concourse of approving people. The news of the repeal of the act was received here May sixteenth, and there was great rejoicing. Parson Smith says: — "Our people are mad with drink and joy: bells ringing, drums beating, colors flying, the court-house illuminated and some others, and a bonfire, and a deluge of drunkenness." The parson lighted up his house. In August, 1767, a mob removed Enoch Ilsley's rum and sugar from the custom-house, which had been seized for breach of the revenue act, and a mob, in July, 1768, rescued from the jail two men, John Huston and John Sanborn, who had been convicted for being concerned in the riot. November 13, 1771, Arthur Savage, the controller, was mobbed. This was an outbreak of popular feeling and three men named Sandford, Stone and Armstrong were committed for trial on the charge of 'participating in it. The enforcement of the revenue laws, which had been practically a dead letter, was obnoxious to the colonists. The cause of the mob is a question, although William Tyng's schooner was seized for smuggling only a fortnight before, which may have had connection with it. In February, 1774, the committee here wrote to that of Boston that "neither the Parliament of Great Britain, nor any other power on earth, has any right to lay tax on us except by our consent or the consent of those whom we choose to represent us." Also, "Our cause is just and we doubt not fully consonant to the will of God. In Him, therefore, let us put our trust, let our hearts be obedient to the dictates of His sovereign will and let our hands and hearts be always ready to unite in zeal for the common good and transmit to our children that sacred freedom which our fathers have transmitted to us and which they purchased with their purest blood." When the port of Boston was closed by the British, June fourteenth, it caused a strong feeling of sympathy here. The patriots muffled the First Parish bell and tolled it without cessation from sunrise until nine o'clock in the evening. At a meeting of the inhabitants the committee were ordered to write a sympathizing letter to the committee of Boston "acquainting them that we look upon them as suffering for the common cause of American liberty, that we highly applaud them for the determination they have made to endure their distresses till they shall know the result of a Continental Congress, and would beg leave to recommend them to persevere in their patience and resolution, and that so far as our abilities will extend we will encourage and support them." September twenty-first, about five hundred men from the eastern towns of the county assembled here, about one-half being armed, "to humble" Sheriff William Tyng, who also held a colonel's commission under Gen. Gage. A county convention, composed of delegates of the nine towns, met the same day at Alice Greele's tavern to take into consideration the alarming condition of the public affairs. The people who were then near Tyng's house (south corner of Franklin and Middle Streets) chose a committee to see if the convention would summon Tyng before them, which they did, when he was asked if he would act under the late act of Parliament, and he replied that he had not and would not except by the general consent of the county. This reply was read to the people, who voted that it was satisfactory, and they then returned peaceably to their homes. In the afternoon, at the town-house, the convention passed resolutions, of which it has been said: — "In point of clearness, ability and sound reasoning they will not suffer in comparison with any productions of that day." On March 2, 1775, the sloop John and Mary, Capt. Henry Hughes, arrived with the rigging, sails and stores for Capt. Thomas Coulson's mast-ship, then building, and the committee of inspection decided by a vote of fourteen to five, that to allow her to land her cargo and fit out the vessel would be a violation of the compact of the colonies called the "American Association." They directed that the vessel's outfit be returned to England without breaking the packages. This decision was confirmed by the county convention of March eighth, by a vote of twenty-three to three. This resulted in the coming of Capt. Henry Mowat in the sloop-of-war Canceau, to protect Coulson in the rigging and loading of his ship, and subsequently the burning of the town. Capt. Coulson built the mast-ship for Mr. Garnet, a merchant of Bristol, England. The

following is an extract from a letter of the chairman of the

committee to Samuel Freeman, dated April 12, 1775.

At a meeting of the committee of inspection held March 3, 1775, there were present, Enoch Freeman, Daniel Ilsley, Benjamin Titcomb, Enoch Ilsley, John Waite, Stephen Waite, Benjamin Mussey, William Owen, Samuel Knight, Jedediah Cobb, John Butler, Jabez Jones, Smith Cobb, Peletiah March, Pearson Jones, Joseph Noyes, Samuel Freeman, Joseph McLellan and Theophilus Parsons. They voted, among other matters, " That this committee will exert their utmost endeavors to prevent all the inhabitants of this town from engaging in riots, tumults and insurrections." At the March town-meeting, in 1775, a general overturn in the town officers in favor of the times was made. The town had been dominated by the Tory and timid element who whined for inaction. This was the first effort of the patriots to assume control of affairs, but' it was not until Mowat had burned the town that they decided on an aggressive policy. The news of the Battle of Lexington was received here April twenty-first before daylight. The war had actually begun. The militia gathered and some started for Cambridge, but after a march of about thirty miles were ordered to return. Then was raised Col. Edmund Phinney's regiment in which was Capt. David Bradish's company from the Neck. The selectmen sent Capt. Joseph McLellan and Capt. Joseph Noyes to secure powder for the town, and with them was sent the following letter to the Committee of Safety at Boston.

In the early part of May, occurred the "Thompson War" in which Col. Phinney's men played a prominent part. The histories of that event are all written from the standpoint of the timid merchants and Tories. The men that composed that "mob from the country," as Mowat called them, were the most respectable and prominent men in the towns where they lived. They were simply zealous patriots who showed their valor on many a hard-fought battle-field in the war that followed. The capture of Mowat by Col. Thompson's men was no part of their plan, hut was simply a circumstance. They intended to capture his vessel, and the officers had resolved themselves into a hoard of war, admitted the officers of the Neck companies, voted by a considerable majority that Capt. Mowat's vessel ought to be destroyed, and had appointed a committee of their number to consider in what manner it should be done. Parson Deane says, under date of May eleventh, "Committee of militia remain sitting." It was only by the most strenuous efforts of the people of Falmouth Neck, that the soldiers were prevented from carrying out their purpose. Now we can see that they should have been allowed to have attempted it. Mrs. Anne Wilson, a daughter of Col. Samuel March, who was a girl of eighteen at the time, said when she was a very old lady, " that if the Committee of Safety had followed Col. Thompson's advice in May, Falmouth would not have been burned in October." The woods where Thompson's "spruce" company concealed themselves were between the Grand Trunk and Tukey's Bridge, and were a growth of small pines. There were no bridges there then. Tukey's Bridge was not built until 1796. When Lieut. Hogg, threatened to burn the town if Capt. Mowat was not released at a certain hour, the following is said to have been the reply of Col. Thompson. He had an impediment in his speech, and his answer was: — "F-f-fire away! f-f-fire away! every gun you fire, I will c-c-cut off a joint." They sacked Coulson's house and drank his liquor, which he expected to drink himself; but such is war. Col. Thompson was a portly man, somewhat corpulent, not tall, but apparently of robust constitution. He had strong mental powers, was witty in conversation, but uneducated, and is said to have been fierce in appearance. He wrote to the Committee of Safety April 29, 1776: "Finding that the sword is drawn first on their side, that we shall be animated with that noble spirit that wise men ought to be until our just rights and liberties are secured to us. Sir, my heart is with every true son of America. If any of my friends inquire for me, inform them that I make it my whole business to pursue those measures recommended by the Congresses." Calvin Lombard of Gorham fired the first gun at Falmouth Neck. It was not the one heard round the world, but it has been ringing in our ears ever since. He was inspired to the act by the spirit of liberty, not Coulson's rum, as that was not flavored with rebellion. The following petition of a committee of the militia, who sacked Coulson's and Tyng's houses, to the General Court, over a year after the event, shows that they fully realized what they were doing and is proof that they were no drunken mob, hut patriots, who came here to do their country important service and were willing to sacrifice their lives, if necessary, to rid the colonies of a troublesome enemy.

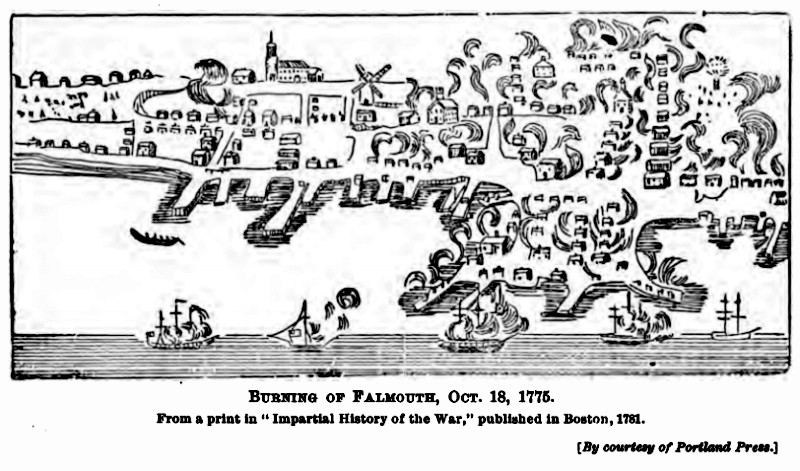

Col. Phinney's regiment left for Cambridge in July, leaving the town guarded by Capt. Joseph Noyes' and Capt. Samuel Knights' companies, that served until December. Enoch Freeman, Benjamin Muzzy, John Brackett and William Owen were selectmen in 1775, and they were ordered " to deliver to every person a quarter of a pound of powder, who was destitute of it, but who had a gun and was willing to defend the country." The next important event was the burning of the town by Capt. Mowat, October 18, 1775. Four days before, he visited Damariscove Islands, seized seventy-eight sheep and three fat hogs, not offering to pay for them, and because the owner objected Mowat burned the house in which he lived. The house was owned by Daniel Knight, but was occupied by John Wheeler, who owned the sheep and hogs. The sheep were valued at £39, the hogs at £8, and the house at £66, 13s, 4d, making a total loss of £113, 13s, 4d, That was the character of Mowat, and when our forefathers denounced him they knew who they were talking about. If Mow at had been proud of the burning of Falmouth Neck, he would have mentioned it in stating his meritorious services in America. He arrived here the sixteenth; the next day warped his vessels up opposite the town; that night he sent his letter ashore and the inhabitants delivered eight small arms to get time. The next morning, the eighteenth, the people met at the court-house and "resolved by no means to deliver up the four cannon and the small arms." Our forefathers, almost unarmed, in the face of four war vessels with guns shotted and already run out, made this resolve. Portland in the Past says, "No more fearless and patriotic action by a deliberate body of people in such an exposed and helpless condition was taken during the struggle of the colonies."

The horrors of the burning of the town have been vividly described by the historians, but some figures may make us realize the extent of the destruction. The fleet fired upwards of three thousand shot and a large number of carcasses and bombs. They destroyed one hundred and thirty-six houses and two hundred and seventy-eight other buildings, making a total of four hundred and fourteen buildings burned. They turned out of doors one hundred and sixty families, and there were hut about one hundred dwelling-houses left. The selectmen said, " All the compact part of the Town is gone;" and of the remaining buildings they said, "They are mostly the refuse of the Town." Every vessel of considerable size was burned except two which the enemy carried away. The total loss was about £55,000. The first house burned was on Middle Street, near where King & Dexter's store now stands (No. 269), and was occupied by Josiah Shaw as a dwelling and saddler's shop. No person of the town was killed and but one, Reuben Clough, seriously injured. Many of the families were obliged to move into the country, and those that remained were obliged to seek shelter wherever it could be found, in barns and woodhouses, where they simply existed. The Committee now realizing their defenseless condition wrote to Gen. Washington at Cambridge, the twenty-first, asking for a garrison, and received the following reply: —

The following letter written by Col. Reuben Fogg of Scarborough, to Gen. Washington, two days after the burning of the town, has never been published.

This John Armstrong was sent to Washington. He turned him over to the Provincial Congress, which gave him liberty to depart. Soloman Bragdon and Major Libby were on guard at the First Parish meeting-house during the bombardment. They caught a man setting fire to the church and took him to Cambridge. An

address distributed in the army at Cambridge, dated November 21,

1775, said:

Mercy

Warren wrote:

Gen.

Jedediah Preble, chairman of the Committee of Safety, wrote January

5, 1776, to Samuel Freeman at Watertown: —

November first, the British man-of-war Cerebus arrived in the harbor with four hundred men on hoard She was a thirty-six gun frigate, commanded by Capt. John Symons, and was the vessel that brought generals Burgoyne, Clinton and Howe to America, arriving at Boston, May 25, 1775. It was on her deck that Burgoyne made his famous remark: "What! ten thousand peasants keep five thousand king's troops shut up! Well let us get in, and we'll soon find elbow room." The Cerebus took part in the Battle of Bunker Hill, being then commanded by Capt. Chad, and she carried the official account of that battle to England, arriving at Portsmouth, England, July twenty-fifth. The news had been received July nineteenth, by another vessel, and the London papers, for weeks, were filled with the melancholy details of the battle taken from the letters of the survivors. July thirty-first, a ship cleared at the London custom-house, for Boston, with two thousand coffins. The Cerebus brought hack the letters of recall to Gen. Gage, arriving September sixth. The following letter from Dr. Deane, written three days after the arrival of the vessel; explains her visit and also confirms the fact that the mercantile part of the community were not at first in favor of the war. The early patriots of the Neck were the artisans and yeomanry, who afterwards became our leading citizens, and property owners. The letter also shows the extent the people of the town suffered from the cowardly burning by Mowat. The patriotic efforts of that people command our admiration, for the next spring every able-bodied man was in the service and their zeal until the close of the war is worthy of all praise In honoring them we honor ourselves. This letter probably has never before been made public, but remained in the archives of Massachusetts until Dr. Charles E. Banks found it and sent it to me a few months ago. It is addressed to Hon Benjamin Greenleaf of Newburyport, Massachusetts, who was a member of the General Court.

When the committee of the town went on board the Cerebus to inform Capt. Symons that he could have no sheep or cattle, even if he would pay for them, he kept the committee. Then the patriots seized George Lyde, the collector, and Joseph Domette, both well-known Tories, and confined them as hostages, whereupon they wrote to Capt. Symons stating their situation as prisoners, and he then released the committee. The captain did not enforce his threats, hut the vessel sailed away. Evidently he was glad to avoid any conflict with men who had the spirit of defiance as exhibited by the patriots here then assembled to defend the remains of the town. Gen. Washington, on receipt of a letter from Enoch Moody, chairman of the committee, dated November 1, no doubt sent Col. Edmund Phinney to take command of the military operations on Falmouth Neck until the arrival of Col. Joseph Frye, November 25, who had been assigned to duty here. In the early part of the year 1776, there was great activity in the town in raising soldiers and sending them to the army to assist. at the siege of Boston. That year Falmouth Neck was garrisoned by a battalion of four companies, under Captains Benjamin Hooper, Tobias Lord, William Crocker and William Lithgow, jr. Another company, Capt. Briant Morton's was stationed at Cape Elizabeth, building Fort Hancock, on the present site of Fort Preble. Col. Frye was promoted to be a brigadier general January 10, 1776, and he joined the Continental army soon after. Then Maj. Daniel Ilsley was the commanding officer here until the appointment of Jonathan Mitchell, March 29, as colonel, with Maj. Ilsley second in command, and James Sullivan as commissary. Gen. Frye resigned his commission in the army, April 23, 1776. In June, the General Court made provisions for a company of matrosses to be stationed in the forts here, and Capt. Abner Lowell raised a company of fifty men, which was increased to eighty the next year, and they may have remained in the service until the fall of 1779, hut the size of the company must have been reduced. There was considerable dissatisfaction with Col. Mitchell among the officers, and matters were finally referred to the council for settlement, with the result that Col. Mitchell received the following order: —

The selectmen in 1776 were Stephen Waite, Joseph Noyes, John Johnson and Humphrey Merrill. This year, most of the work was done on the fortifications here, and Major Ilsley in a letter said, "The soldiers have done a great deal of work fortifying, and with a cheerfulness which is not common amongst soldiers." The battalion was discharged the last of November. The news of the declaration of our independence was brought here by Joseph Titcomb, then nineteen years of age. Willis says that he was mate of the letter of marque Fox, became the commander of a privateer and introduced, about 1790, the fashion of wearing pantaloons in Portland, he having adopted them while abroad. He was a selectman of the town ten years. July 30, the militia was mustered here and men were drafted to reenforce the Northern army, then at Fort Ticonderoga and vicinity. These soldiers probably joined Capt. John Wentworth's company, in Col. Aaron Willard's regiment, and served in that army from August to December, five months. Parson Smith says, December 4, "Every fourth man is drafted for the army everywhere." This was to fill up the new three years' regiments that were going into service January 1, 1777. In the early part of the year 1777, these men were being organized into companies and sent off to join their regiments in the service. Maj. Daniel Ilsley, the muster master, recorded the mustering and paying of bounties to four hundred and twenty-one men here before July, 1780. In March, Jedediah Preble wrote from Cambridge, "The province of Maine and town of Falmouth in particular are highly applauded by the General Court for being foremost of any part of the state (Massachusetts) in furnishing their quotas for the army." In April, 1778, the government mentioned the conduct of Falmouth as highly commendable, manly and patriotic in their glorious exertions to raise volunteers to reenforce the Continental army." The harbor was a favorite resort of privateers and many of their prizes were brought here. The Retrieve, Capt. Joshua Stone, sailed from here in 1776. She was equipped with ten carriage and sixteen swivel guns and carried eighty men, as reported to the government; but a soldier wrote in his journal, September 22, 1776, that she sailed "about five o'clock; she has 11 carriage guns, 6 swivel and 2 cohorns," and he adds, "May she meet with success." October 2, he says: "Capt. Stone sent in a prize sloop of Tories last night." The Retrieve was captured about October 1, 1777, by the British frigate Glasgow. The Fox was built here in 1777, and went on her first cruise November 1. Her letters of marque, it is said, were issued to John Fox, Benjamin Titcomb and Nathaniel Deering, but probably others were interested in her. She was pierced for twenty guns, but they sailed with but four and no swords, and fitted scythes into suitable handles for boarding pikes. When out about eight days she captured a ship of eighteen guns, with a valuable cargo, and carried her into Boston. This rich prize furnished all the arms and equipments necessary, and was profitable to the owners; but this was her most successful cruise. There were other privateers fitted out here of which little is known. The news of the surrender of Gen. Burgoyne was received here October 26; there was great rejoicing and a general illumination of the few houses left. If a house was not properly lighted a window was broken and a string of candles thrown in with the orders to light up. Around Alice Greele's tavern was the center of demonstration. Here Benjamin Tukey was mortally wounded by the premature discharge of a cannon. Bottles of wine and buckets of punch were passed out of her windows to the crowd outside, who were very noisy. Several of the inhabitants subscribed "to purchase a good beef ox to distribute to the families of the non-commissioned officers and soldiers belonging in Falmouth, who were engaged in the capture of Gen. Burgoyne and his army." Col. John Waite was the chairman of the committee to make the purchase and attend to the duty. In the winter of 1777-78, the people of Old Falmouth felt the anguish of her sons, who half-clothed and half-starved, were recording their devotion to liberty with the blood from their feet on the white snow at Valley Forge. The sufferings of those patriots we cannot describe, but their names will go down through generations to come, among the noblest heroes of our country. In February, Col. Waite issued the following advertisement: —

April 13, 1778, the French Frigate La Sensible arrived in the harbor, bringing the despatches to our government, with the news that France had formally and openly acknowledged American independence. The forts and the armed vessels then in the harbor saluted the frigate and she saluted them in return. The frigate remained here five days. The year 1778 was a year when patriotism was at its lowest ebb. Reenforcements were ordered for Washington's army in March, and Old Falmouth raised Capt. Jesse Partridge's company of fifty men by voluntary enlistment. They joined the army on the Hudson River, were assigned to Col. John Greaton's Third Massachusetts regiment, and served until November 1. The General Court, June 23, voted "that the town of Falmouth, having raised fifty men by volunteer enlistment, are exempt from furnishing men as per resolve April 2, 1778." This year the small-pox broke out here and a pesthouse was built, but the disorder was of a mild character. Parson Smith says June 20, "Our people are mad about inoculation." Under date of January 3, 1779, Parson Smith records, " Our company of soldiers is reduced to ten." These were the garrison soldiers in the fortifications. In July, Col. Jonathan Mitchell's Cumberland County regiment was raised and embarked for the Bagaduce expedition and after that disaster they returned, but were so destitute of arms and equipments that the Falmouth committee soon discharged over four companies as unfit for service, and but three of those remained here and at Cape Elizabeth. Col. Henry Jackson's regiment was ordered here from Kittery, arriving August 29, and marched to Boston, September 7. This was a crack Boston regiment, fully uniformed and equipped, and had participated in the battles of Monmouth and Quaker Hill. They camped above the Eastern Cemetery. After these regiments were relieved the town was garrisoned by about four hundred militia for about a month. The committee stated, September 13, "that the militia in this county are at present in a situation incapable of defending us in case of an attack, principally owing to their ignorance and neglect of the principal officers of the brigade." August 18, Enoch Freeman, in behalf of the Committee, wrote the following letter to the Council in regard to the situation here in that critical time, which shows that Jackson's regiment was sent here at the Committee's request.

The Council sent the following reply:

August thirtieth, Stephen Hall, chairman of the Committee of Safety, said of the soldiers and seamen from Bagaduce, that they were "in the greatest distress imaginable" and also that the "affairs here are in the wildest confusion." September third, a prize ship was brought into the harbor that had "on board two hundred soldiers for the British army and stores and goods to a large amount." She was one of the two of the enemy's vessels that were captured by the Continental frigates Boston and Dean. At the opening of the year 1780, the prospects were gloomy indeed. Provisions were scarce and very high. The currency had depreciated to such an extent that it was almost worthless, and the British and Tories were troublesome on the Penobscot. Gen. Peleg Wadsworth was placed in command of the department of Maine, and he arrived here April sixth, in the Protector, twenty-six guns, Capt. John Foster Williams. On board was a midshipman, then eighteen years of age, who afterwards became Commodore Edward Preble, whom Portland is proud to own as her son. Gen.

Wadsworth at once organized the regiment of Col. Joseph Prime for

service in this state, and the following officers were appointed: —

The headquarters of the regiment were here and five companies were stationed on the Neck, with Capt. Ethan Moore's at Cape Elizabeth. Those that remained here were under command of Capts. Joseph Pride, Josiah Bragdon, Josiah Davis, Daniel Clark and Jedediah Goodwin. Gen. Wadsworth sailed for Camden July twenty-fifth, and Major Ulmer served on Penobscot Bay, where others of the regiment were sent later. The service of these companies was uneventful and they were discharged, excepting thirty men, December sixth. March 1, 1781, the people of the Neck were much alarmed because of a rumor that the British at Bagaduce were to come and capture the town, and March sixth, the militia regiment was called out, but nothing came of it. The war was now drawing to a close and afterwards the town was probably garrisoned by only a small guard. Capt. Joseph McLellan, Capt. John Reed, Capt. Peter Merrill and Segt. John Bagley were in command of soldiers here during the years 1781, 1782 and 1783. Falmouth Neck was alarmed many times during the war and many times the militia was called cut for defense, but never were obliged to engage the enemy. Several times the militia regiments were mustered here for a draft to fill the quotas, hut in certain cases Falmouth was excused because she had filled hers by voluntary enlistments. The Neck was probably garrisoned from the commencement of the struggle until its close, with from a sergeant's guard to nearly a thousand men, as occasion seemed to require. April 4, 1783, Samuel Rollins was killed by the bursting of a cannon, while celebrating the cessation of hostilities. He was probably the last man on Falmouth Neck to lose his life in the war for our independence. The History of Portland says: —

The sons of Old Falmouth heard the first gun fired at Lexington and were ever afterwards ready to go wherever needed. James Sullivan wrote from here January 31, 1776:—

Falmouth soldiers were in the trenches nine months at the siege of Boston, took part in the battles of Long Island and White Plains, and marched to reenforce the Northern army at Fort Ticonderoga in 1776 and 1777. They were in the thickest of the fight in the obstinate battles of Hubbardston and Stillwater, and at Saratoga followed Arnold in his mad charges against the British lines, where ten days later they witnessed the surrender of Gen. Burgoyne and his army. Falmouth men joined Washington's army near Philadelphia and were among those patriots at Valley Forge who raised a monument to the fortitude and patience of the American soldier. On that hot sultry day, June 28, 1778, they were writing history at Monmouth: there Capt. Paul Ellis of this town had his leg shot off, and bled to death before medical assistance arrived. They guarded Burgoyne's army at Cambridge and showed their valor at Quaker Hill. It was Capt. Peter Warren's Falmouth company that first reached the heights and formed at Bagaduce. Of the four hundred, who made this assault, one hundred were killed or wounded. This was the only bright spot in that expedition, hut it has been said "that no more brilliant exploit than this was accomplished by our forces during the war." In 1780, soldiers from Falmouth were in the army, doing their duty faithfully to their country, and when at the final muster in November, 1783, Falmouth boys answered "here" with almost eight and one-half years service to their credit. The people of Old Falmouth sent tons of beef and large quantities of other supplies to the army and in their poverty they helped the poor of Boston. Our soldiers baptized almost every battlefield with their blood, consecrating their very lives to liberty. Long since the little mounds .on the battlefields have been leveled by the hand of time, but the memories of those men are kept green around many a hearthstone of their descendants. We must not forget the gallant sailors of our privateers, whose tales of adventure have thrilled their children and grandchildren, and are passed from generation to generation. Many of those brave patriots suffered and died in the prison ships and were buried with those thousands of unknown at Brooklyn, on the shores of Wallabout Bay. The noble women of the town stood shoulder to shoulder with their husbands and brothers in the contest. They spun, wove, and made blankets and clothing for the soldiers' comfort, and in many ways added strength to the cause. By chance, a list of forty of the soldiers' families who were supplied by the town has been saved from the destroyed records of that time. Wealth was not the patriot's boast, and honest poverty was no disgrace. This list means much. They were long-service men in the Continental army, who had lost their all and, in order that they might remain with the regiments and fight their country's battles, the town furnished their families with the necessities of life. It was a mutual arrangement. This roll of honor, both for the soldiers and their wives, brings to our minds the woman's share in the struggle. These wives, with the devotion and fortitude of their time, kept together their little families, waiting patiently for peace and the return of those liberty-loving Americans. A list of soldiers' families supplied by Old Falmouth, from the town records of May 8, 1779: —

The Loyalists or Tories, as they were called, were a troublesome element on Falmouth Neck at the commencement of the struggle for the colonists' rights. They were influential, quite numerous and active, but were most thoroughly hated by the patriots. They had been men of standing and had not the grievances of those less favored than themselves and therefore thought the rebellion against the king unjustifiable. Many who at first were opposed to the stand taken by the colonists, afterwards became zealous patriots, and there were many of humble circumstances who held Tory principles, hut did not make themselves obnoxious to the patriots, and remained here during the war. The most conspicuous of the Tories left the town and sacrificed their all for opinion's sake; were loyal to their government, and we should not reproach them now for their fidelity to their king. They simply did nothing towards establishing our free republic and therefore they cannot share in the glory of it. Several Tories returned after the war and were respected citizens of the town, some of whom recovered their property for a small sum. The Absentee Act of 1778 drew the line sharply between the Tories and the patriots. Under that act the property of the Tories was sold as if they, in fact, were dead. If they returned they were committed to jail until they could be sent out of the state, and if they returned the second time, they were to suffer on conviction the pains of death without the benefit of the clergy. Among the most prominent Tories of the Neck were the custom officers. George Lyde, the collector, came here from Boston to succeed Francis Waldo in March, 1770. His fees were £150 per year. Thomas Oxnard, son-in-law of Gen. Jedediah Preble, was deputy and Daniel Wyer, Sr., was tide surveyor. Arthur Savage, the comptroller of customs, lived where the Casco House was afterwards, about where the Casco National Bank is now situated. Here is where he was mobbed. Thomas Child, the weigher and gauger, was the only customs officer who remained and joined the colonists. He continued in charge of the collection district until 1787. Parson John Wiswell went with Capt. Mowat in 1775, as did Francis Waldo. Jeremiah Pote, and Robert Pagan, his son-in-law, both notorious Tories, left the town. Thomas Wyer, another son-in-law of Pote, went also. Thomas Coulson, who made much trouble for our forefathers by insisting on rigging and loading his mast-ship, sailed away and never returned. Edward Oxnard, a son-in-law of Jabez Fox, who, with his brother, returned after the war and became respected citizens, went also. Thomas Ross, James Wildridge, Joshua Eldridge and Samuel Longfellow, mariners, left the town, as did John Wright, the merchant. Col. William Tyng, the sheriff of the county, a descendant of George Cleaves, the first settler, whose father, Com. Edward Tyng and his grandfather, Capt. Edward Tyng, were identified with the history of Portland, and were gallant officers in their county's service, although he left the reputation of "a true man in every relation of life," caused the patriots of this county much concern because of his allegiance to his king. Col. Tyng went to New York in 1775 and joined the British army, in which he held a commission, and while there befriended several of his old friends and neighbors who were unfortunate enough to be confined in the prison ships, among whom was Edward Preble, afterwards the commodore, and Carey McLellan of Gorham. Col. Tyng, on his first visit to Gorham after the war, appeared at the meeting-house door and no one offered him a seat, until Carey McLellan stepped forward and escorted him to his pew. The citizens had voted not to allow a Tory to live in the town, and it is said that no other man would have dared to have offered Tyng a seat. Col. Tyng moved to Gorham in 1793, where as a generous, charitable and kind-hearted man, his death in 1807, was deeply lamented. He was buried in the Eastern Cemetery under the shade of the old pine tree where his monument now stands. He had no children. True

patriots they, for be it understood,

They left their country for their country's good. The story of Falmouth Neck in the Revolution, has not all been told, but that part of Old Falmouth, now Portland, did well its part in that struggle. It suffered and contributed as much, in proportion to its means, as any town in the colonies. Our noble ancestors left to us the heritage of a free country for which they are entitled to the gratitude of each succeeding generation. We have a beautiful city with much interesting history, and it is our duty so to guard it, that when it becomes the possession of the generations to come, they will be as proud of the people of our time, as we are of our ancestors. Where's the coward that wold not dare To fight for such a land?

_______________________________________

1 This is not intended as a full history of the Revolutionary period at Falmouth Neck, although all important events are noticed, but is supplementary and explanatory of what has been published in Willis' History of Portland, Goold's Portland in the Past, and Freeman's Smith and Deane's Journal. |

Web and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio

1999-2009

(Return to Web Text-ures)