| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Fairy Tales From The Arabian Nights Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

THE STORY OF THE FISHERMAN AND GENIE PART I THERE was once a very old fisherman, so poor, that he could scarcely earn enough to maintain himself, his wife, and three children. He went every day to fish betimes in the morning; and imposed it as a law upon himself not to cast his nets above four times a day. He went one morning by moonlight, and coming to the seaside, undressed himself, and cast in his nets. As he drew them towards the shore, he found them very heavy, and thought he had a good draught of fish, at which he rejoiced within himself; but perceiving a moment after that, instead of fish, there was nothing in his nets but the carcass of an ass, he was much vexed. When the fisherman, vexed

to have

made such a sorry draught, had mended his nets, which the carcass of

the ass

had broken in several places, he threw them in a second time; and, when

he drew

them, found a great deal of resistance, which made him think he had

taken

abundance of fish; but he found nothing except a basket full of gravel

and

slime, which grieved him extremely. "O Fortune!" cried he in a

lamentable tone, "be not angry with me, nor persecute a wretch who

prays

thee to spare him. I came hither from my house to seek for my

livelihood, and

thou pronouncest death against me. I have no trade but this to subsist

by; and,

notwithstanding all the care I take, I can scarcely provide what is

absolutely

necessary for my family." Having finished this

complaint, he

threw away the basket in a fret, and washing his nets from the slime,

cast them

the third time; but brought up nothing except stones, shells, and mud.

Nobody

can express his dismay; he was almost beside himself. However, when the

dawn

began to appear, he did not forget to say his prayers, like a good

Mussulman,

and afterwards added this petition: "Lord, thou knowest that I cast my

nets only four times a day; I have already drawn them three times,

without the

least reward for my labour: I am only to cast them once more; I pray

thee to

render the sea favourable to me, as thou didst to Moses." The fisherman, having

finished his

prayer, cast his nets the fourth time; and when he thought it was time,

he drew

them as before, with great difficulty; but, instead of fish, found

nothing in

them but a vessel of yellow copper, which by its weight seemed to be

full of

something; and he observed that it was shut up and sealed, with a

leaden seal

upon it. This rejoiced him: "I will sell it," said he, "at the

foundry, and with the money arising from the produce buy a measure of

corn."

He examined the vessel on all sides, and shook it, to see if what was

within

made any noise, but heard nothing. This, with the impression of the

seal upon

the leaden cover, made him think there was something precious in it. To

try

this, he took a knife, and. opened it with very little trouble. He

presently

turned the mouth downward, but nothing came out, which surprised him

extremely.

He set it before him, and while he looked upon it attentively, there

came out a

very thick smoke which obliged him to retire two or three paces away. The smoke ascended to the

clouds,

and extending itself along the sea and upon the shore, formed a great

mist,

which, we may well imagine, did mightily astonish the fisherman. When

the smoke

was all out of the vessel, it reunited itself, and became a solid body,

of

which there was formed a genie twice as high as the greatest of giants.

At the

sight of a monster of such unwieldy bulk, the fisherman would fain have

fled,

but he was so frightened that he could not go one step. "Solomon," cried the

genie

immediately, "Solomon, great prophet, pardon, pardon; I will never more

oppose thy will, I will obey all thy commands." When the fisherman heard

these words

of the genie, he recovered his courage, and said to him, "Proud spirit,

what is it that you say? It is above eighteen hundred years since the

prophet

Solomon died, and we are now at the end of time. Tell me your history,

and how

you came to be shut up in this vessel." The genie, turning to the

fisherman

with a fierce look, said, "You must speak to me with more civility; you

are very bold to call me a proud spirit." "Very well," replied the

fisherman, "shall I speak to you with more civility, and call you the

owl

of good luck?" "I say," answered the

genie, "speak to me more civilly, before I kill thee." "Ah!" replied the

fisherman, "why would you kill me? Did I not just now set you at

liberty,

and have you already forgotten it?" "Yes, I remember it,"

said

the genie, "but that shall not hinder me from killing thee: I have only

one favour to grant thee." "And what is that?" said

the fisherman. "It is," answered the

genie, "to give thee thy choice, in what manner thou wouldst have me

take

thy life." "But wherein have I

offended

you?" replied the fisherman. "Is that your reward for the good

service I have done you?" "I cannot treat you

otherwise," said the genie; "and that you may be convinced of it,

hearken to my story. "I am one of those

rebellious

spirits that opposed the will of Heaven: all the other genii owned

Solomon, the

great prophet, and submitted to him. Sacar and I were the only genii

that would

never be guilty of a mean thing: and, to avenge himself, that great

monarch

sent Asaph, the son of Barakhia, his chief minister, to apprehend me.

That was

accordingly done. Asaph seized my person, and brought me by force

before his

master's throne. "Solomon, the son of

David,

commanded me to quit my way of living, to acknowledge his power, and to

submit

myself to his commands: I bravely refused to obey, and told him I would

rather

expose myself to his resentment than swear fealty, and submit to him,

as he

required. To punish me, he shut me up in this copper vessel; and to

make sure

that I should not break prison, he himself stamped upon this leaden

cover his

seal, with the great name of God engraven upon it. Then he gave the

vessel to

one of the genii who submitted to him, with orders to throw me into the

sea,

which was done, to my sorrow. "During the first hundred

years' imprisonment, I swore that if anyone would deliver me before the

hundred

years expired, I would make him rich, even after his death: but that

century

ran out, and nobody did me the good office. During the second, I made

an oath

that I would open all the treasures of the earth to anyone that should

set me at

liberty; but with no better success. In the third, I promised to make

my

deliverer a potent monarch, to be always near him in spirit, and to

grant him

every day three requests, of what nature soever they might be: but this

century

ran out as well as the two former, and I continued in prison. At last,

being

angry, or rather mad, to find myself a prisoner so long, I swore that

if

afterwards anyone should deliver me, I would kill him without mercy,

and grant

him no other favour but to choose what kind of death he would die; and,

therefore, since you have delivered me to-day, I give you that choice."

This tale afflicted the

poor

fisherman extremely: "I am very unfortunate," cried he, "to have

done such a piece of good service to one that is so ungrateful. I beg

you to

consider your injustice and to revoke such an unreasonable oath;

pardon me,

and heaven will pardon you; if you grant me my life, heaven will

protect you

from all attempts against yours." "No, thy death is

resolved

on," said the genie, "only choose how you will die." The fisherman, perceiving

the genie

to be resolute, was terribly grieved, not so much for himself as for

his three

children, and the misery they must be reduced to by his death. He

endeavoured

still to appease the genie, and said, "Alas! be pleased to take pity on

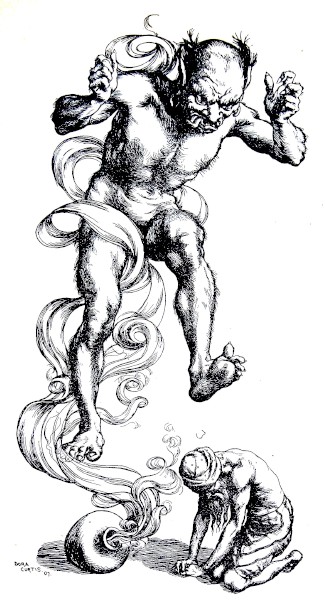

me, in consideration of the good service I have done you." "I have told thee already," replied the genie, "it is for that very reason I must kill thee."  "I SAY," ANSWERED THE GENIE, "SPEAK TO ME MORE CIVILLY, BEFORE I KILL THEE" "That is very strange,"

said the fisherman, "are you resolved to reward good with evil? The

proverb says, 'He who does good to one who deserves it not is always

ill

rewarded.' I must confess I thought it was false; for in reality there

can be

nothing more contrary to reason, or to the laws of society.

Nevertheless, I find

now by cruel experience that it is but too true." "Do not lose time,"

replied the genie, "all thy reasonings shall not divert me from my

purpose; make haste, and tell me which way you choose to die." Necessity is the mother

of

invention. The fisherman bethought himself of a stratagem. "Since I

must

die then," said he to the genie, "I submit to the will of heaven;

but, before I choose the manner of death, I conjure you by the great

name which

was engraven upon the seal of the prophet Solomon, the son of David, to

answer

me truly the question I am going to ask you." The genie finding himself

bound to a

positive answer trembled, and replied to the fisherman, "Ask what thou

wilt, but make haste." The genie having thus

promised to

speak the truth, the fisherman said to him, "I wish to know if you were

actually in this vessel. Dare you swear it by the Great Name?" "Yes," replied the genie,

"I do swear by that Great Name that I was; and it is a certain

truth." "In good faith," answered

the fisherman, "I cannot believe you. The vessel is not capable of

holding

one of your feet, and how is it possible that your whole body could lie

in

it?" "I swear to thee,

notwithstanding," replied the genie, "that I was there just as thou

seest me here. Is it possible that thou dost not believe me after this

great

oath that I have taken?" "Truly, I do not," said

the fisherman; "nor will I believe you unless you show it me." Upon which the body of

the genie was

dissolved, and changed itself into smoke, extending itself as formerly

upon the

sea and shore, and then at last, being gathered together, it began to

re-enter

the vessel, which it continued to do by a slow and equal motion in a

smooth and

exact way, till nothing was left out, and immediately a voice said to

the fisherman,

"Well, now, incredulous fellow, I am all in the .vessel; do not you

believe me now?" The fisherman, instead of

answering

the genie, took the cover of lead, and speedily shut the vessel.

"Genie," cried he, "now it is your turn to beg my favour, and to

choose which way I shall put you to death; but it is better that I

should throw

you into the sea, whence I took you: and then I will build a house upon

the

bank, where I will dwell, to give notice to all fishermen who come to

throw in

their nets to beware of such a wicked genie as thou art, who hast made

an oath

to kill him that shall set thee at liberty." The genie, enraged, did

all he could

to get out of the vessel again; but it was not possible for him to do

it, for

the impression of Solomon's seal prevented him. So, perceiving that

the

fisherman had got the advantage of him, he thought fit to dissemble his

anger.

"Fisherman," said he, in a pleasant tone, "take heed you do not

do what you say, for what I spoke to you before was only by way of

jest, and you

are to take it no otherwise." "Oh, genie!" replied the

fisherman, "thou who wast but a moment ago the greatest of all genii,

and

now art the least of them, thy crafty discourse will avail thee

nothing. Back

to the sea thou shalt go. If thou hast been there already so long as

thou hast

told me, thou mayst very well stay there till the day of judgment. I

begged of

thee, in God's name, not to take away my life, and thou didst reject my

prayers; I am obliged to treat thee in the same manner." The genie omitted nothing

that might

prevail upon the fisherman. "Open the vessel," said he; "give me

my liberty, I pray thee, and I promise to satisfy thee to thy heart's

content." "Thou art a mere

traitor,"

replied the fisherman; "I should deserve to lose my life if I were such

a

fool as to trust thee. Notwithstanding the extreme obligation thou wast

under

to me for having set thee at liberty, thou didst persist in thy design

to kill

me; I am obliged in my turn, to be as hard-hearted to thee." "My good friend

fisherman,"

replied the genie, "I implore thee once more not to be guilty of such

cruelty; consider that it is not good to avenge oneself, and that, on

the other

hand, it is commendable to return good for evil; do not treat me as

Imama

treated Ateca formerly." "And what did Imama do to

Ateca?" replied the fisherman. "Ho!" said the genie,

"if you have a mind to hear, open the vessel: do you think that I can

be

in a humour to tell stories in so strait a prison? I will tell you as

many as

you please when you let me out." "No," said the fisherman,

"I will not let you out; it is vain to talk of it. I am just going to

throw you to the bottom of the sea." "Hear me one word more,"

cried the genie. "I promise to do thee no hurt; nay, far from that, I

will

show thee how thou mayest become exceedingly rich." The hope of delivering

himself from

poverty prevailed with the fisherman. "I might listen to you,"

said he, "were there any credit to be given to your word. Swear to me

by

the Great Name that you will faithfully perform what you promise, and I

will

open the vessel. I do not believe you will dare to break such an oath."

The genie swore to him,

and the

fisherman immediately took off the covering of the vessel. At that very

instant

the smoke came out, and the genie having resumed his form as before,

the first

thing he did was to kick the vessel into the sea. This action

frightened the

fisherman. "Genie," said he,

"what is the meaning of that? Will you not keep the oath you just now

made?" The genie laughed at the

fisherman's

fear, and answered: "No, fisherman, be not afraid; I only did it to

please

myself, and to see if thou wouldst be alarmed at it; but to persuade

thee that

I am in earnest, take thy nets and follow me." As he spoke these words,

he

walked before the fisherman, who took up his nets, and followed him,

but with

some distrust. They passed by the town, and came to the top of a

mountain, from

whence they descended into a vast plain, and presently to a great pond

that lay

betwixt four hills. When they came to the

side of the

pond, the genie said to the fisherman, "Cast in thy nets and catch

fish." The fisherman did not doubt of catching some, because he saw a

great number in the pond; but he was extremely surprised when he found

that

they were of four colours — white, red, blue, and yellow. He threw in

his nets,

and brought out one of each colour. Having never seen the like, he

could not

but admire them, and, judging that he might get a considerable sum for

them, he

was very joyful. "Carry those fish," said

the genie, "and present them to the sultan; he will give you more money

for them than ever you had in your life. You may come every day to fish

in this

pond; and I give you warning not to throw in your nets above once a

day,

otherwise you will repent it. Take heed, and remember my advice."

Having

spoken thus, he struck his foot upon the ground, which opened and

swallowed up

the genie. The fisherman, being

resolved to

follow the genie's advice exactly, forebore casting in his nets a

second time,

and returned to the town very well satisfied with his fish, and making

a

thousand reflections upon his adventure. He went straight to the

sultan's

palace. The sultan was much

surprised when

he saw the four fishes. He took them up one after another, and looked

at them

with attention; and, after having admired them a long time, he said to

his

first vizier, "Take those fishes to the handsome cook-maid that the

Emperor of the Greeks has sent me. I cannot imagine but that they must

be as

good as they are fine." The vizier carried them

himself to

the cook, and delivering them into her hands, "Look," said he,

"here are four fishes newly brought to the sultan; he orders you to

dress

them." And having so said, he returned to the sultan his master, who

ordered

him to give the fisherman four hundred pieces of gold of the coin of

that

country, which he accordingly did. The fisherman, who had

never seen so

much cash in his lifetime, could scarcely believe his own good

fortune. He

thought it must be a dream, until he found it to be real, when he

provided

necessaries for his family with it. As soon as the sultan's

cook had

cleaned the fishes, she put them upon the fire in a frying-pan with

oil; and

when she thought them fried enough on one side, she turned them upon

the other;

but scarcely were they turned when the wall of the kitchen opened, and

in came

a young lady of wonderful beauty and comely size. She was clad in

flowered

satin, after the Egyptian manner, with pendants in her ears, a necklace

of

large, pearls, bracelets of gold garnished with rubies, and a rod of

myrtle in

her hand. She came towards the frying-pan, to the great amazement of

the cook,

who stood stock-still at the sight, and, striking one of the fishes

with the

end of the rod, said, "Fish, fish, art thou in thy duty?" The fish having answered nothing, she repeated these words, and then the four fishes lifted up their heads all together, and said to her, "Yes, yes; if you reckon, we reckon; if you pay your debts, we pay ours; if you fly, we overcome, and are content." As soon as they had finished these words, the lady overturned the frying-pan, and entered again into the open part of the wall, which shut immediately, and became as it was before.  THE LADY OVERTURNED THE FRYING-PAN The cook was greatly

frightened at

this, and, on coming a little to herself, went to take up the fishes

that had

fallen upon the hearth, but found them blacker than coal, and not fit

to be

carried to the sultan. She was grievously troubled at it, and began to

weep

most bitterly. "Alas!" said she, "what will become of me? If I

tell the sultan what I have seen, I am sure he will not believe me, but

will be

enraged." While she was thus

bewailing

herself, in came the grand vizier, and asked her if the fishes were

ready. She

told him all that had happened, which we may easily imagine astonished

him;

but, without speaking a word of it to the sultan, he invented an excuse

that

satisfied him, and sending immediately for the fisherman, bade him

bring four

more such fish, for a misfortune had befallen the other ones. The

fisherman,

without saying anything of what the genie had told him, but in order

to excuse

himself from bringing them that very day, told the vizier that he had a

long

way to go for them, but would certainly bring them to-morrow. Accordingly the fisherman

went away

by night, and, coming to the pond, threw in his nets betimes next

morning, took

four such fishes as before, and brought them to the vizier at the hour

appointed. The minister took them himself, carried them to the kitchen,

and

shut himself up all alone with the cook: she cleaned them and put them

on the

fire, as she had done the four others the day before. When. they were

fried on

one side, and she had turned them upon the other, the kitchen wall

opened, and

the same lady came in with the rod in her hand, struck one of the

fishes, spoke

to it as before, and all four gave her the same answer. After the four fishes had

answered

the young lady, she overturned the frying-pan with her rod, and

retired into

the same place of the wall from whence she had come out. The grand

vizier being

witness to what had passed said, "This is too surprising and

extraordinary

to be concealed from the sultan; I will inform him." Which he

accordingly

did, and gave him a very faithful account of all that had happened. The sultan, being much

surprised,

was impatient to see it for himself. He immediately sent for the

fisherman, and

said to him, "Friend, cannot you bring me four more such fishes?" The fisherman replied,

"If your

majesty will be pleased to allow me three days' time, I will do it."

Having obtained his time, he went to the pond immediately, and at the

first

throwing in of his net, he caught four fishes, and brought them at

once to the

sultan. The sultan rejoiced at it, as he did not expect them so soon,

and

ordered him four hundred pieces of gold. As soon as the sultan had

received the

fish, he ordered them to be carried into his room, with all that was

necessary

for frying them; and having shut himself up there with the vizier, the

minister

cleaned them, put them in the pan upon the fire, and when they were

fried on

one side, turned them upon the other; then the wall of the room opened,

but

instead of the young lady there came out a black man, in the dress of a

slave,

and of gigantic stature, with a great green staff in his hand. He

advanced

towards the pan, and touching one of the fishes with his staff; said to

it in a

terrific voice, "Fish, art thou in thy duty?" At these words, the

fishes raised up

their heads, and answered, "Yes, yes; we are; if you reckon, we reckon;

if

you pay your debts, we pay ours; if you fly, we overcome, and are

content." The fishes had no sooner

finished

these words than the black man threw the pan into the middle of the

room, and

reduced the fishes to a coal. Having done this, he retired fiercely,

and

entering again into the hole of the wall, it shut, and appeared just as

it did

before. "After what I have seen,"

said the sultan to the vizier, "it will not be possible for me to be

easy

in my mind. These fish without doubt signify something extraordinary."

He

sent for the fisherman, and said to him, "Fisherman, the fishes you

have

brought us make me very uneasy; where did you catch them?" "Sir," answered he,

"I fished for them in a pond situated between four hills,

beyond the

mountain that we see from here." "Know'st thou that pond?"

said the sultan to the vizier. "No, sir," replied the

vizier, "I never so much as heard of it: and yet it is not sixty years

since I hunted beyond that mountain and thereabouts." The sultan asked the

fisherman how

far was the pond from the palace. The fisherman answered

that it was

not above three hours' journey. Upon this, there being

daylight

enough beforehand, the sultan commanded all his court to take horse,

and the

fisherman served them for a guide. They all ascended the mountain, and

at the

foot of it they saw, to their great surprise, a vast plain, that nobody

had

observed till then, and at last they came to the pond which they found

really

to be situated between four hills, as the fisherman had said. The water

of it

was so transparent that they observed all the fishes to be like those

which the

fisherman had brought to the palace. The sultan stood upon the

bank of

the pond, and after beholding the fishes with admiration, he demanded

of his

emirs and all his courtiers if it was possible that they had never seen

this

pond, which was within so little a way of the town. They all answered

that they

had never so much as heard of it. "Since you all agree,"

said he, "that you never heard of it, and as I am no less astonished

than

you are, I am resolved not to return to my palace till I know how this

pond

came here, and why all the fish in it are of four colours." Having spoken thus he ordered his court to

encamp; and immediately his pavilion and the tents of his household

were

pitched upon the banks of the pond. THE STORY OF THE FISHERMAN AND

GENIE

PART II WHEN night came, the

sultan retired

to his pavilion and spoke to the grand vizier by himself. "Vizier, my mind is very

uneasy; this pond transported hither; the black man that appeared to us

in my

room, and the fishes that we heard speak; all this does so much excite

my

curiosity that I cannot resist the impatient desire I have to satisfy

it. To

this end I am resolved to withdraw alone from the camp, and I order you

to keep

my absence secret." The grand vizier said

much to turn

the sultan from this design. But it was to no purpose; the sultan was

resolved

on it, and would go. He put on a suit fit for walking, and took his

scimitar;

and as soon as he saw that all was quiet in the camp, he went out

alone, and

went over one of the hills without much difficulty. He found the

descent still

more easy, and, when he came to the plain, walked on till the sun rose,

and

then he saw before him, at a considerable distance, a great building.

He

rejoiced at the sight, and hoped to learn there what he wanted to know.

When he

came near, he found it was a magnificent palace, or rather a very

strong

castle, of fine black polished marble, and covered with fine steel, as

smooth as

a looking-glass. Being highly pleased that he had so speedily met with

something worthy of his curiosity, he stopped before the front of the

castle,

and considered it attentively. The gate had two doors,

one of them

open; and though he might have entered, he yet thought it best to

knock. He

knocked at first softly, and waited for some time. Seeing nobody, and

supposing

they had not heard him, he knocked harder the second time, and then

neither

seeing nor hearing anybody, he knocked again and again. But nobody

appeared,

and it surprised him extremely; for he could not think that a castle in

such

good repair was without inhabitants. "If there is nobody in it," said

he to himself, "I have nothing to fear; and if there is, I have

wherewith

to defend myself." At last he entered, and

when he came

within the porch, he called out, "Is there nobody here to receive a

stranger, who comes in for some refreshment as he passes by?" He

repeated

the same two or three times; but though he shouted, nobody answered.

The silence

increased his astonishment: he came into a very spacious court, and

looked on

every side, to see if he could perceive anybody; but he saw no living

thing. Perceiving nobody in the

court, the

sultan entered the great halls, which were hung with silk tapestry; the

alcoves

and sofas were covered with stuffs of Mecca, and the porches with the

richest

stuffs of India, mixed with gold and silver. He came afterwards into a

magnificent court, in the middle of which was a great fountain, with a

lion of

massive gold at each corner; water issued from the mouths of the four

lions,

and this water, as it fell, formed diamonds and pearls, while a jet of

water,

springing from the middle of the fountain, rose almost as high as a

cupola

painted after the Arabian manner. On three sides the castle

was

surrounded by a garden, with flower-pots, fountains, groves, and a

thousand

other fine things; and to complete the beauty of the place, an infinite

number

of birds filled the air with their harmonious songs, and always stayed

there,

nets being spread over the trees, and fastened to the palace to keep

them in.

The sultan walked a long time from apartment to apartment, where he

found

everything very grand and magnificent. Being tired with walking, he sat

down in

a room which had a view over the garden, and there reflected upon what

he had

already seen, when all of a sudden he heard lamentable cries. He

listened with

attention, and distinctly heard these sad words: "O

Fate!

thou who wouldst not suffer me longer to enjoy a happy lot, and hast

made me

the most unfortunate man in the world, forbear to persecute me, and by

a speedy

death put an end to my sorrows. Alas! is it possible that I am still

alive,

after so many torments as I have suffered?" The sultan, touched at

these pitiful

complaints, rose up, and made toward the place whence he heard the

voice; and

when he came to the gate of a great hall, he opened it, and saw a.

handsome

young man, richly dressed, seated upon a throne raised a little above

the

ground. Melancholy was painted on his looks. The sultan drew near, and

saluted

him; the young man returned him his salute, by a low bow with his head;

but not

being able to rise up, he said to the sultan, "My lord, I aria very

sure

you deserve that I should rise up to receive you, and do you all

possible

honour; but I am hindered from doing so by a very sad reason, and

therefore

hope you will not take it ill." "My lord," replied the

sultan, "I am very much obliged to you for having so good an opinion of

me: as to your not rising, whatever your excuse may be, I heartily

accept it.

Being drawn hither by your complaints, and distressed by your grief, I

come to

offer you my help. I flatter myself that you would willingly tell me

the

history of your misfortunes; but pray tell me first the meaning of the

pond

near the palace, where the. fishes are of four colours. What is this

castle?

how came you to be here? and why are you alone?" Instead of answering

these

questions, the young man began to weep bitterly. "How inconstant is

fortune;" cried he: "she takes pleasure in pulling down those she had

raised up. Where are they who enjoy quietly their happiness, and whose

day is

always clear and serene?" The sultan, moved with

compassion,

prayed him forthwith to tell him the cause of his excessive grief.

"Alas!

my lord,' replied the young man, "how can I but grieve, and my eyes be

inexhaustible fountains of tears?" At these words he lifted up his

gown,

and showed the sultan that he was a man only from the head to the

waist, and

that the other half of his body was black marble. The sultan was strangely

surprised

when he saw the deplorable condition of the young man. "That which you

show me," said he, "while it fills me with horror, so excites my

curiosity that I am impatient to hear your history, which, no doubt, is

very

extraordinary, and I am persuaded that the pond and the fishes have

some part

in it ; therefore I beg you to tell it me. You will find some comfort

in doing

so, since it is certain that unfortunate people obtain some sort of

ease in

telling their misfortunes." "I will not refuse you this satisfaction," replied the young man, "though I cannot do it without renewing my grief. But I give you notice beforehand, to prepare your ears, your mind, and even your eyes, for things which surpass all that the most extraordinary imagination can conceive.  THE CITY OF THE BLACK ISLES "You must know, my lord,"

he began, "that my father Mahmoud was king of this country. This is the

kingdom of the Black Isles, which takes its name from the four little

neighbouring mountains; for those mountains were formerly islands: the

capital, where the king, my father, had his residence, was where that

pond now

is. "The king, my father,

died when

he was seventy years of age I had no sooner succeeded him than I

married, and

the lady I chose to share the royal dignity with me was my cousin.

Nothing was

comparable to the good understanding between us, which lasted for five

years.

At the end of that time I perceived that the queen, my cousin, took no

more

delight in me. "One day I was inclined

to

sleep after dinner, and lay down upon the sofa. Two of her ladies came

and sat

down, one at my head, and the other at my feet, with fans in their

hands to

moderate the heat, and to hinder the flies from troubling me. They

thought I

was fast asleep, and spoke very low; but I only shut my eyes, and heard

every

word they said. "One of them said to the

other,

'Is not the queen much in the wrong not to love such an amiable prince

as this?

' "'Certainly,' replied the

other; for my part, I do not understand it. Is it possible that he does

not

perceive it? ' "'Alas!' said the first,

'how

would you have him perceive it? She mixes every evening in his drink

the juice

of a certain herb, which makes him sleep so soundly that she has time

to go

where she pleases; then she wakes him by the smell of something she

puts under

his nose.' "You may guess, my lord,

how

much I was surprised at this conversation; yet, whatever emotion it

excited in

me, I had command enough over myself to dissemble, and pretended to

awake without

having heard one word of it. "The queen returned, and

with

her own hand presented me with a cup full of such water as I was

accustomed to

drink; but instead of putting it into my mouth, I went to a window that

was

open, and threw out the water so quickly that she did not notice it,

and I put

the cup again into her hands, to persuade her that I had drunk it. "Soon after, believing

that I

was asleep, though I was not, she got up with little precaution, and

said, so

loudly, that I could hear it distinctly, Sleep, and may you never wake

again!' "As soon as the queen, my

wife,

went out, I got up in haste, took my scimitar, and followed her so

quickly,

that I soon heard the sound of her feet before me, and then walked

softly after

her, for fear of being heard. She passed through several gates, which

opened on

her pronouncing some magical words; and the last she opened was that of

the

garden, which she entered. I stopped there that she might not perceive

me, and

looking after her as far as the darkness permitted, I perceived that

she

entered a little wood, whose walks were guarded by thick palisades. I

went

thither by another way, and slipping behind the palisades of a long

walk, I saw

her walking there with a man. "I listened carefully,

and

heard her say, I do not deserve to be upbraided by you for want of

diligence;

you need but command me, you know my power. I will, if you desire it,

before

sunrise, change this great city, and this fine palace, into frightful

ruins,

which shall be inhabited by nothing but wolves, owls, and ravens. If

you wish

me to transport all the stones of those walls, so solidly built, beyond

the

Caucasus, and out of the bounds of the habitable world, speak but the

word, and

all shall undergo a change.' "As the queen finished

these words,

the man and she came to the end of the walk, turned to enter another,

and

passed before me. I had already drawn my scimitar, and the man being

nearest to

me, I. struck him on the neck, and made him fall to the ground. I

thought I had

killed him, and therefore retired speedily, without making myself known

to the

queen, whom I chose to spare, because she was my kinswoman. "The blow I had given was

mortal; but she preserved his life by the force of her enchantments; in

such a

manner, however, that he could not be said to be either dead or alive.

As I

crossed the garden, to return to the palace, I heard the queen cry out

lamentably. "When I returned home,

being

satisfied with having punished the villain, I went to sleep; and, when

I awoke

next morning, found the queen there too. "Whether she slept or not

I

cannot tell, but I got up and went out without making any noise. I held

my

council, and at my return the queen, clad in mourning, her hair hanging

about

her eyes, and part of it torn off, presented herself before me, and

said: Sir,

I come to beg your majesty not to be surprised to see me in this

condition. I

have just now received, all at once, three afflicting pieces of news.' "Alas! what is the news,

madam?

' said I. "The death of the queen

my dear

mother,' answered she; that of the king my father, killed in battle;

and that

of one of my brothers, who has fallen down a precipice.' "I was not ill-pleased

that she

made use of this pretext to hide the true cause of her grief. Madam,'

said I, I

am so far from blaming your grief that I assure you I share it. I

should very

much wonder if you were insensible of so great a loss. Mourn on, your

tears are

so many proofs of your good nature. I hope, however, that time and

reason will

moderate your grief.' "She retired into her

apartment, and gave herself wholly up to sorrow, spending a whole year

in

mourning and afflicting herself. At the end of that time she begged

leave of me

to build a burying-place for herself, within the bounds of the palace,

where

she would remain, she told me, to the end of her days. I agreed, and

she built

a stately palace, with a cupola, that may be seen from hence, and she

called it

the Palace of Tears. When it was finished she caused the wounded

ruffian to be

brought thither from the place where she had caused him to be carried

the same

night, for she had hindered his dying by a drink she gave him. This she

carried

to him herself every day after he came to the Palace of Tears. "Yet with all her

enchantments

she could not cure the wretch. He was not only unable to walk and to

help

himself, but had also lost the use of his speech, and gave no sign of

life but

by his looks. Every day she made him two long visits. I was very well

informed

of all this, but pretended to know nothing of it. "One day I went out of

curiosity to the Palace of Tears to see how the queen employed herself,

and

going to a place where she could not see me, I heard her speak thus to

the

scoundrel: I am distressed to the highest degree to see you in this

condition.

I am as sensible as yourself of the tormenting pain you endure, but,

dear soul,

I constantly speak to you, and you do not answer me; how long will you

be

silent? Speak only one word. I would prefer the pleasure of always

seeing you

to the empire of the universe.' "At these words, which

were

several times interrupted by her sighs and sobs, I lost all patience,

and,

showing myself, came up to her, and said, 'Madam, you have mourned

enough. It

is time to give over this sorrow, which dishonours us both. You have

too much

forgotten what you owe to me and to yourself.' "'Sir,' said she, 'if you

have any kindness left for me, I beseech you to put no restraint upon

me. Allow

me to give myself up to mortal grief, which it is impossible for time

to

lessen.' "When I saw that what I

said,

instead of bringing her to her duty, served only to increase her rage,

I gave

over, and retired. She continued for two whole years to give herself up

to

excessive grief. "I went a second time to

the

Palace of Tears while she was there. I hid myself again, and heard her

speak

thus: It is now three years since you spoke one word to me. Is it from

insensibility or contempt? No, no, I believe nothing of it. O tomb!

tell me by

what miracle thou becamest the depositary of the rarest treasure that

ever was

in the world.' "I must confess I was

enraged

at these words, for, in short, this creature so much doted upon, this

adored

mortal, was not such an one as you might imagine him to have been. He

was a

black Indian, a native of that country. I say I was so enraged that I

appeared

all of a sudden, and addressing the tomb in my turn, cried, O tomb! why

dost

not thou swallow up this pair of monsters?' "I had scarcely finished

these

words when the queen, who sat by the Indian, rose up like a fury. Cruel

man! '

said she, thou art the cause of my grief. I have dissembled it but too

long; it

is thy barbarous hand which hath brought him into this lamentable

condition,

and thou art so hard-hearted as to come and insult me.' "'Yes,' said I, in a

rage, it

was I who chastised that monster according to his deserts. 'I ought to

have

treated thee in the same manner. I repent now that I did not do it.

Thou hast

abused my goodness too long.' "As I spoke these words I

drew

out my scimitar, and lifted up my hand to punish her; but she,

steadfastly

beholding me, said, with a jeering smile, 'Moderate thy anger.' At the

same time

she pronounced words I did not understand, and added, By virtue of my

enchantments, I

command thee immediately to become half marble and half man.'

Immediately I

became such as you see me now, a dead man among the living, and a

living man

among the dead. "After this cruel

magician,

unworthy of the name of a queen, had metamorphosed me thus, and brought

me into

this hall, by another enchantment she destroyed my capital, which was

very

flourishing and full of people; she abolished the houses, the public

places and

markets, and reduced it to the pond and desert field, which you may

have seen;

the fishes of four colours in the pond are the four sorts of people, of

different religions, who inhabited the place. The white are the

Mussulmans; the

red, the Persians, who worship fire; the blue, the Christians; and the

yellow,

the Jews. The four little hills were the four islands that gave the

name to this

kingdom. I learned all this from the magician, who, to add to my

distress, told

me with her own mouth these effects of her rage. But this is not all;

her

revenge was not satisfied with the destruction of my dominions and the

metamorphosis of my person; she comes every day, and gives me over my

naked

shoulders an hundred blows with an ox-goad, which makes me all over

gore; and,

when she has done, she covers me with a coarse stuff of goat's-hair,

and throws

over it this robe of brocade that you see, not to do me honour, but to

mock

me." After this, the young

king could not

restrain his tears; and the sultan's heart was so pierced with the

story, that

he could not speak one word to comfort him. Presently he said: "Tell me

whither this perfidious magician retires, and where may be the unworthy

wretch

who is buried before his death." "My lord," replied the

prince, "the man, as I have already told you, is in the Palace of

Tears,

in a handsome tomb in form of a dome, and that palace joins the castle

on the

side of the gate. As to the magician, I cannot tell precisely whither

she

retires, but every day at sunrise she goes to see him, after having

executed

her vengeance upon me, as I have told you; and you see I am not in a

condition

to defend myself against such great cruelty. She carries him the drink

with

which she has hitherto prevented his dying, and always complains of his

never

speaking to her since he was wounded." "Unfortunate prince,"

said

the sultan, "never did such an extraordinary misfortune befall any man,

and those who write your history will be able to relate something that

surpasses all that has ever yet been written." While the sultan

discoursed with the

young prince, he told him who he was, and for what end he had entered

the

castle; and thought of a plan to release him and punish the

enchantress, which

he communicated to him. In the meantime, the night being far spent,

the sultan

took some rest but the poor young prince passed the night without

sleep, as

usual, having never slept since he was enchanted; but he had now some

hope of

being speedily delivered from his misery. Next morning the sultan

got up

before dawn, and, in order to execute his design, he hid in a corner

his upper

garment, which would have encumbered him, and went to the Palace of

Tears. He

found it lit up with an infinite number of tapers of white wax, and a

delicious

scent issued from several boxes of fine gold, of admirable workmanship,

all

ranged in excellent order. As soon as he saw the bed where the Indian

lay, he

drew his scimitar, killed the wretch without resistance, dragged his

corpse

into the court of the castle, and threw it into a well. After this, he

went and

lay down in the wretch's bed, took his scimitar with him under the

counterpane,

and waited there to execute his plan. The magician arrived

after a little

time. She first went into the chamber where her husband the King of the

Black

Islands was, stripped him, and beat him with the ox-goad in a most

barbarous

manner. The poor prince filled the palace with his lamentations to no

purpose,

and implored her in the most touching manner to have pity on him; but

the cruel

woman would not give over till she had given him an hundred blows. "You had no compassion,"

said she, "and you are to expect none from me." After the enchantress had

given the

king, her husband, an hundred blows with the ox-goad, she put on again

his

covering of goat's-hair, and his brocade gown over all; then she went

to the

Palace of Tears, and, as she entered, she renewed her tears and

lamentations;

then approaching the bed, where she thought the Indian was: "Alas!"

cried she, addressing herself unawares to the sultan; "my sun, my life,

will you always be silent? Are you resolved to let me die, without

giving me

one word of comfort. My soul, speak one word to me at least, I implore

you." The sultan, as if he had

waked out

of a deep sleep, and counterfeiting the language of the Indians,

answered the

queen in a grave tone, "There is no strength or power but in God alone,

who is almighty." At these words the

enchantress, who

did not expect them, gave a great shout, to signify her excessive joy.

"My

dear lord," cried she, "do I deceive myself? Is it certain that I

hear you, and that you speak to me?" "Unhappy wretch," said

the

sultan, "art thou worthy that I should answer thee?" "Alas!" replied the

queen,

"why do you reproach me thus?" "The cries," replied he,

"the groans and tears of thy husband, whom thou treatest every day with

so

much indignity and barbarity, hinder me from sleeping night and day. I

should

have been cured long ago, and have recovered the use of my speech,

hadst thou

disenchanted him. That is the cause of the silence which you complain

of."

"Very well," said the

enchantress; "to pacify you, I am ready to do whatever you command me.

Would

you have me restore him as he was?" "Yes," replied the

sultan,

"make haste and set him at liberty, that I be no more disturbed with

his

cries." The enchantress went

immediately out

of the Palace of Tears; she took a cup of water, and pronounced words

over it,

which caused it to boil, as if it had been on the fire. Then she went

into the

hall, to the young king her husband, and threw the water upon him,

saying,

"If the Creator of all things did form thee so as thou art at present,

or

if He be angry with thee, do not change. But if thou art in that

condition

merely by virtue of my enchantments, resume thy natural shape, and

become what

thou wast before." She had scarcely spoken

these words,

when the prince, finding himself restored to his former condition, rose

up

freely, with all imaginable joy, and returned thanks to God. Then the enchantress said

to him,

"Get thee gone from this castle, and never return here on pain of

death!" The young king, yielding

to

necessity, went away from the enchantress, without replying a word, and

retired

to a remote place, where he patiently awaited the success of the plan

which the

sultan had so happily begun. Meanwhile the enchantress

returned

to the Palace of Tears, and, supposing that she still spoke to the

black man,

said, "Dearest, I have done what you ordered." The sultan continued to

counterfeit

the language of the blacks. "That which you have just now done," said

he, "is not sufficient for my cure. You have only eased me of part of

my

disease; you must cut it up by the roots." "My lovely black man,"

replied she, "what do you mean by the roots?" "Unfortunate woman,"

replied the sultan, "do you not understand that I mean the town, and

its

inhabitants, and the four islands, which thou hast destroyed by thy

enchantments?

The fishes every night at midnight raise their heads out of the pond,

and cry

for vengeance against thee and me. This is the root cause of the delay

of my

cure. Go speedily, restore things as they were, and at thy return I

will give

thee my hand, and thou shalt help me to rise." The enchantress, filled

with hope

from these words, cried out in a transport of joy, "My heart, my soul,

you

shall soon be restored to health, for I will immediately do what you

command

me." Accordingly she went that moment, and when she came to the brink

of

the pond, she took a little water in her hand, and sprinkling it, she

pronounced some words over the fishes and the pond, and the city was

immediately restored. The fishes became men, women, and children;

Mahometans, Christians,

Persians, or Jews; freemen or slaves, as they were before; every one

having

recovered his natural form. The houses and shops were immediately

filled with

their inhabitants, who found all things as they were before the

enchantment.

The sultan's numerous retinue, who had encamped in the largest square,

were

astonished to see themselves in an instant in the middle of a large,

handsome,

and well-peopled city. To return to the

enchantress. As

soon as she had effected this wonderful change, she returned with all

diligence

to the Palace of Tears. "My dear," she cried, as she entered, "I

come to rejoice with you for the return of your health: I have done all

that

you required of me; then pray rise, and give me your hand." "Come near," said the

sultan, still counterfeiting the language of the blacks. She did so.

"You

are not near enough," said he, "come nearer." She obeyed. Then

he rose up, and seized her by the arm so suddenly, that she had not

time to

discover who it was, and with a blow of his scimitar cut her in two, so

that

one half fell one way, and the other another. This done, he left the

carcass at

the place, and going out of the Palace of Tears, he went to look for

the young

King of the Black Isles, who was waiting for him with great impatience.

"Prince,"

said he, embracing him, "rejoice; you have nothing to fear now; your

cruel

enemy is dead." The young prince returned

thanks to

the sultan in such a manner as showed that he was thoroughly sensible

of the

kindness that he had done him, and in return, wished him a long life

and all

happiness. "You may henceforward," said the sultan, "dwell

peaceably in your capital, unless you will go to mine, where you shall

be very

welcome, and have as much honour and respect shown you as if you were

at

home." "Potent monarch, to whom

I am

so much indebted," replied the king, "you think, then, that you are

very near your capital?" "Yes," said the sultan,

"I know it; it is not above four or five hours' journey." "It will take you a whole

year," said the prince. "I do believe, indeed, that you came hither

from your capital in the time you speak of, because mine was enchanted;

but

since the enchantment is taken off, things are changed. However, this

.shall

not prevent my following you, were it to the utmost corners of the

earth. You

are my deliverer, and that I may show you that I shall acknowledge this

during

my whole life, I am willing to accompany you, and to leave my kingdom

without

regret." The sultan was extremely

surprised

to learn that he was so far from his dominions, and could not imagine

how it

could be. But the young King of the Black Islands convinced him beyond

a

possibility of doubt. Then the sultan replied, "It is no matter: the

trouble of returning to my own country is sufficiently recompensed by

the

satisfaction of having obliged you, and by acquiring you for a son; for

since

you will do me the honour to accompany me, as I have no child, I look

upon you

as such, and from this moment I appoint you my heir and successor." The conversation between

the sultan

and the King of the Black Islands concluded with the most affectionate

embraces; after which the young prince was totally taken up in making

preparations for his journey, which were finished in three weeks' time,

to the

great regret of his court and subjects, who agreed to receive at his

hands one

of his nearest kindred for their king. At last the sultan and

the young

prince began their journey, with a hundred camels laden with

inestimable riches

from the treasury of the young king, followed by fifty handsome

gentlemen on

horseback, well mounted and dressed. They had a very happy journey; and

when

the sultan, who had sent couriers to give notice of his delay, and of

the

adventure which had occasioned it, came near his capital, the principal

officers he had left there came to receive him, and to assure him that

his long

absence had occasioned no alteration in his empire. The inhabitants

came out

also in great crowds, received him with acclamations, and made public

rejoicings for several days. On the day after his

arrival, the

sultan gave all his courtiers a very ample account of the events which,

contrary to his expectation, had detained him so long. He told them he

had

adopted the King of the Four Black Islands, who was willing to leave a

great

kingdom to accompany and live with him; and as a reward for their

loyalty, he

made each of them presents according to their rank. As for the fisherman,

since he was

the first cause of the deliverance of the young prince, the sultan gave

him a

plentiful fortune, which made him and his family happy for the rest of

their

days. |