| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Fairy Tales From The Arabian Nights Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

THE SEVENTH AND LAST VOYAGE OF SINBAD THE SAILOR

BEING

returned from my sixth voyage, I absolutely laid aside all thoughts of

travelling any farther; for, besides that my years now required rest, I

was

resolved no more to expose myself to such risk as I had run; so that I

thought

of nothing but to pass the rest of my days in quiet. One day, as I was treating some of my friends, one of my

servants came and told me that an officer of the caliph asked for me. I

rose

from the table, and went to him. "The caliph," said he, "has

sent me to tell you that he must speak with you." I followed the

officer

to the palace, where, being presented to the caliph, I saluted him by

prostrating myself at his feet. "Sinbad," said he to me, "I

stand in need of you; you must do me the service to carry my answer and

present

to the King of Serendib. It is but just I should return his civility." This

command of the caliph to me was like a clap of thunder. "Commander of

the

Faithful," replied I, "I am ready to do whatever your majesty shall

think fit to command me; but I beseech you most humbly to consider what

I have

undergone. I have also made a vow never to go out of Bagdad." Here I

took

occasion to give him a large and particular account of all my

adventures, which

he had the patience to hear out. As soon

as I had finished, "I confess," said he, "that the things you

tell me are very extraordinary, yet you must for my sake undertake this

voyage

which I propose to you. You have nothing to do but to go to the Isle of

Serendib, and deliver the commission which I give you. After that you

are at

liberty to return. But you must go; for you know it would be indecent,

and not

suitable to my dignity, to be indebted to the king of that island."

Perceiving that the caliph insisted upon it, I submitted, and told him

that I

was willing to obey. He was very well pleased at it, and ordered me a

thousand

sequins for the expense of my journey. I

prepared for my departure in a few days, and as soon as the caliph's

letter and

present were delivered to me, I went to Balsora, where I embarked, and

had a

very happy voyage. I arrived at the Isle of Serendib, where I

acquainted the

king's ministers with my commission, and prayed them to get me speedy

audience.

They did so, and I was conducted to the palace in an honourable manner,

where I

saluted the king by prostration, according to custom. That prince knew

me

immediately, and testified very great joy to see me. "O Sinbad," said

he, "you are welcome; I swear to you I have many times thought of you

since, you went hence; I bless the day upon which we see one another

once

more." I made my compliment to him, and after having thanked him for

his

kindness to me, I delivered the caliph's letter and present, which he

received

with all imaginable satisfaction. The

caliph's present was a complete set of cloth of gold, valued at one

thousand

sequins; fifty robes of rich stuff, a hundred others of white cloth,

the finest

of Cairo, Suez, Cusa, and Alexandria; a royal crimson bed, and a second

of

another fashion; a vessel of agate broader than deep, an inch thick,

and half a

foot wide, the bottom of which represented in bas-relief a man with one

knee on

the ground, who held a bow and an arrow, ready to let fly at a lion. He

sent

him also a rich table, which, according to tradition, belonged to the

great

Solomon. The caliph's letter was as follows : "Greeting

in the name of the Sovereign Guide of the Right Way, to the potent and

happy

Sultan, from Abdallah Haroun Alraschid, whom God hath set in the place

of

honour, after his ancestors of happy memory : "We

received your letter with joy, and send you this from the council of

our port,

the garden of superior wits. We hope, when you look upon it, you will

find our

good intention, and be pleased with it. Farewell." The King

of Serendib was highly pleased that the caliph returned his friendship.

A

little time after this audience, I solicited leave to depart, and had

much

difficulty to obtain it. I obtained it, however, at last, and the king,

when he

dismissed me, made me a very considerable present. I embarked

immediately to

return to Bagdad, but had not the good fortune to arrive there as I

hoped. God

ordered it otherwise. Three or

four days after my departure, we were attacked by pirates, who easily

seized

upon our ship. Some of the crew offered resistance, which cost them

their

lives. But as for me and the rest, who were not so imprudent, the

pirates saved

us on purpose to make slaves of us. We were

all stripped, and instead of our own clothes they gave us sorry rags,

and

carried us into a remote island, where they sold us. I fell

into the hands of a rich merchant, who, as soon as he bought me,

carried me to

his house, treated me well, and clad me handsomely for a slave. Some

days

after, not knowing who I was, he asked me if I understood any trade. I

answered

that I was no mechanic, but a merchant, and that the pirates who sold

me had

robbed me of all I had. "But

tell me," replied he, "can you shoot with a bow?" I

answered that the bow was one of my exercises in my youth, and I had

not yet

forgotten it. Then he gave me a bow and arrows, and, taking me behind

him upon

an elephant, carried me to a vast forest some leagues from the town. We

went a

great way into the forest, and when he thought fit to stop he bade me

alight;

then showing me a great tree, "Climb up that tree," said he,

"and shoot at the elephants as you see them pass by, for there is a

prodigious number of them in this forest, and, if any of them fall,

come and

give me notice of it." Having spoken thus, he left me victuals, and

returned to the town, and I continued upon the tree all night. I saw no

elephant during that time, but next morning, as soon as the sun was up,

I saw a

great number: I shot several arrows among them, and at last one of the

elephants fell; the rest retired immediately, and left me at liberty to

go and

acquaint my patron with my booty. When I had told him the news, he gave

me a

good meal, commended my dexterity, and caressed me highly. We

afterwards went

together to the forest, where we dug a hole for the elephant; my patron

intending to return when it was rotten, and to take the teeth, etc., to

trade

with. I

continued this game for two months, and killed an elephant every day,

getting

sometimes upon one tree, and sometimes upon another. One morning, as I

looked

for the elephants, I perceived with an extreme amazement that, instead

of

passing by me across the forest as usual, they stopped, and came to me

with a

horrible noise, in such a number that the earth was covered with them,

and

shook under them. They encompassed the tree where I was with their

trunks

extended and their eyes all fixed upon me. At this frightful spectacle

I

remained immoveable, and was so much frightened that my bow and arrows

fell out

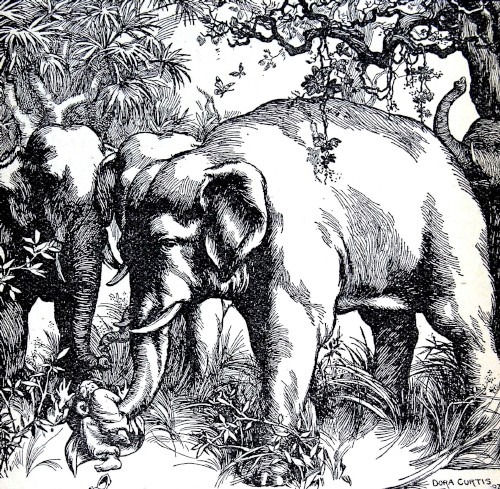

of my hand. My fears were not in vain; for after the elephants had stared upon me for some time, one of the largest of them put his trunk round the root of the tree, and pulled so strong that he plucked it up and threw it on the ground; I fell with the tree, and the elephant taking me up with his trunk, laid me on his back, where I sat more like one dead than alive, with my quiver on my shoulder: then he put himself at the head of the rest, who followed him in troops, and carried me to a place where he laid me down on the ground, and retired with all his companions. Conceive, if you can, the condition I was in: I thought myself to be in a dream; at last, after having lain some time, and seeing the elephants gone, I got up, and found I was upon a long and broad hill, covered all over with the bones and teeth of elephants. I confess to you that this furnished me with abundance of reflections. I admired the instinct of those animals; I doubted not but that this was their burying-place, and that they carried me thither on purpose to tell me that I should forbear to persecute them, since I did it only for their teeth. I did not stay on the hill, but turned towards the city, and, after having travelled a day and a night, I came to my patron; I met no elephant on my way, which made me think they had retired farther into the forest, to leave me at liberty to come back to the hill without any hindrance.  THE ELEPHANT TAKING ME UP WITH HIS TRUNK, LAID ME ON HIS BACK As soon

as my patron saw me: "Ah, poor Sinbad," said he, "I was in great

trouble to know what had become of you. I have been at the forest,

where I

found a tree newly pulled up, and a bow and arrows on the ground, and

after

having sought for you in vain I despaired of ever seeing you more. Pray

tell me

what befell you, and by what good hap you are still alive." I

satisfied his curiosity, and going both of us next morning to the hill,

he

found to his great joy that what I had told him was true. We loaded the

elephant upon which we came with as many teeth as he could carry; and

when we

had returned, "Brother," said my patron "for I

will treat you no more as my slave — after having made

such a discovery as will enrich me, God bless you with all happiness

and

prosperity. I declare before Him that I give you your liberty. I

concealed from

you what I am now going to tell you. "The

elephants of our forest have every year killed a great many slaves,

whom we

sent to seek ivory. Notwithstanding all the cautions we could give

them, those

crafty animals killed them one time or other. God has delivered you

from their

fury, and has bestowed that favour upon you only. It is a sign that He

loves

you, and has use for your service in the world. You have procured me

incredible

gain. We could not have ivory formerly but by exposing the lives of our

slaves,

and now our whole city is enriched by your means. Do not think I

pretend to

have rewarded you by giving you your liberty; I will also give you

considerable

riches. I could engage all our city to contribute towards making your

fortune,

but I will have the glory of doing it myself." To this

obliging discourse I replied, "Patron, God preserve you. Your giving me

my

liberty is enough to discharge what you owe me, and I desire no other

reward

for the service I had the good fortune to do to you and your city, than

leave

to return to my own country." "Very

well," said he, "the monsoon will in a little time bring ships for

ivory. I will send you home then, and give you wherewith to pay your

expenses."

I thanked him again for my liberty, and his good intentions towards me.

I

stayed with him until the monsoon; and during that time we made so many

journeys to the hill that we filled all our warehouses with ivory. The

other

merchants who traded in it did the same thing, for it could not be long

concealed from them. The

ships arrived at last, and my patron himself having made choice of the

ship

wherein I was to embark, he loaded half of it with ivory on my account,

laid in

provisions in abundance for my passage, and obliged me besides to

accept as a

present, curiosities of the country of great value. After I had

returned him a

thousand thanks for all his favours, I went on board. We set sail, and

as the

adventure which procured me this liberty was very extraordinary, I had

it

continually in my thoughts. We

stopped at some islands to take in fresh provisions. Our vessel being

come to a

port on the main land in the Indies, we touched there, and not being

willing to

venture by sea to Balsora, I landed my proportion of the ivory,

resolving to

proceed on my journey by land. I made vast sums by my ivory, I bought

several

rarities, which I intended for presents, and when my equipage was

ready, I set

out in the company of a large caravan of merchants. I was a long time

on the

way, and suffered very much, but endured all with patience, when I

considered

that I had nothing to fear from the seas, from pirates, from serpents,

nor from

the other perils I had undergone. All these fatigues ended at last, and I came safe to Bagdad. I went immediately to wait upon the caliph, and gave him an account of my embassy. That prince told me he had been uneasy, by reason that I was so long in returning, but that he always hoped God would preserve me. When I told him the adventure of the elephants, he seemed to be much surprised at it, and would never have given any credit to it had he not known my sincerity. He reckoned this story, and the other narratives I had given him, to be so curious that he ordered one of his secretaries to write them in characters of gold, and lay them up in his treasury. I retired very well satisfied with the honours I received and the presents which he gave me; and after that I gave myself up wholly to my family, kindred and friends.  |