| 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to Fairy Tales Content Page Click here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

| 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to Fairy Tales Content Page Click here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

|

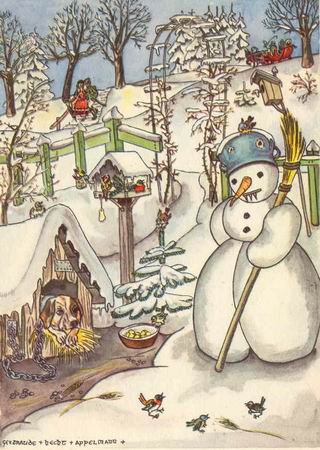

“It is so wonderfully cold that I feel a cracking all over my body,” said the snowman. “Such a wind can really instill a new life into one. See, how that glowing fellow up there is staring at us!” — he meant the sun which was just about setting. “He will not manage to make me wink with my eyes, nay, I do mean to keep fast my little pieces.” The snowman had, you know, instead of eyes two big three cornered pieces of a tile in his head. His mouth was made of an old rake, thus he had teeth too. He came into the world amidst the boys’ loud shouts of joy, and was welcomed by the tinkling of bells and the sledge-drivers’ cracking of whips. The sun was setting, and the full moon was rising up in the blue air, round and big, bright and glorious. “There he is again from the other side,” said the snowman, and meant to say by that: The sun appears once more. “I have broken his habit of staring like that after all! — Let him hang there and shine so that I can see myself. If only I knew how to set about moving on from the spot. Oh, I have such a mind for moving. If I could do so, I would slide along, down there on the ice as I see the boys sliding along, but I don’t know how to run.” “Wak — wak,” barked the old chained-up watch-dog, who was somewhat hoarse and could not bark his real “bow-bow” of former days. He had caught this hoarseness as a home dog always lying under the stove. “The sun will certainly teach you how to run. That I noticed in the case of your predecessor last winter, and earlier still of his predecessor, Wak-wak. And off they all go!” “I don’t understand you, my dear fellow,” said the snowman. “That one, up there, shall teach me how to run?” He meant the moon. “Why, of course, he was running away a little while ago, as I looked at him firmly. Now, there he comes slinking along from the other side!” “You know nothing at all,” returned the watch-dog. “No wonder, as you were only stuck together just now! The one that you behold is the moon. The one that passed away a while ago, was the sun. He reappears to-morrow, he will certainly teach you how to run down into the water-ditch. We shall soon have a change of weather, which I feel already in my left hind leg, have such a stitch and pain in it: The weather is going to change” “I don’t understand him,” said the snowman, “but my mind misgives me that what he says, is somewhat unpleasant. The one that was so staring and made off afterwards, the sun, as he called him, is not my friend either. That’s what I am feeling!” “Wak — wak!” barked the watch-dog, turning round about himself three times. Then he crept into his kennel to go to sleep. And the weather did change. Towards the morning there lay a thick, damp fog over all the land. At the break of day a breeze was blowing gently, and thereupon an icy wind sprang up, that the cold penetrated through and through. The frosty weather seized one thoroughly, and what a glory it was as the sun was rising! The trees and bushes were spun all over with the hoar-frost like a wood of corals. The branches seemed entirely bedecked with snow-white blossoms. The many delicate ramifications hidden away by the rich foliage during the summer now stood out clearly. It was like a laceweb, bright and white. And a glaring broke forth from each twig. The drooping-birch was stirred by the wind, and so full of life as are only the trees in summer. This was a peculiar splendour! And what a glimmering and sparkling there was, now that the sun was shining like diamond-dust lying on all things everywhere! And radiant diamonds glittered on the snowy covering or, one might also think that countless tiny lights shone yet brighter than the white snow. “Wonderful!” called out a young maiden who entered the garden with a young man. Both remained standing near the snowman watching the glittering trees. “Summer does not afford a more beautiful sight,” said she, and her eyes beamed with delight. “Nor have you ever such a fellow as this one in summertime replied the young man pointed to the snowman. “He is excellent!” The young girl laughed, nodded to the snowman, and walked light-footedly with her friend over the snow, which crunched under their feet, as if they were treading on starch-flour. “Who were the two?” asked the snowman of the watch-dog “You have been here at the yard longer than I, do you know them?” “And how well I know them.” answered the watch-dog. “She has even fondled me, and he has thrown a meat-bone to me. I don’t bite either of them!” “But what do they mean?” asked the snowman, “Engaged couple,” growled the watch-dog. “They are moving into a hut and will gnaw together at one bone. Wak-wak!” “Are both as fine people as you and I?” asked the snowman, “They belong to the master’s family you know,” replied the watch-dog. “How little one knows, when one has come into the world only one day before! Your manner shows that clearly! But I am old and experienced and possess knowledge. I am acquainted with everybody in this house, and I knew a time when I would not lie here at the chain during the cold weather. Wak-wak!” “The cold is wonderful.” said the snowman. “Do tell your story and report! However, you must not make a noise with your chain! There is a cracking all over my body when you do so!” “Wak-wak!” barked the watch-dog. “I was a little young dog, small and nice as they said. In those days, I lay on a velvet chair up there at the castle, and sat in the lap of the highest members of the family. I got kisses on my muzzle and my little paws were wiped with an embroidered handkerchief. I was called “Ami, dear, sweet Ami”. But later on, I grew too tall for them and they gave me to the housekeeper. I moved into the underground dwelling. Just there where you are standing, you can see it. You can look down into the chamber where I played master and mistress, for it was this post I filled at the house-keeper’s. It is true. it was an inferior post to that one upstairs, but it was more pleasant, because I was not permanently caught and pulled to and fro by the children. I got as good food as previously, nay better still! I had a cushion of my own, and there was a stove which is the finest thing on earth in this season! I crept under the stove and was able to hide myself perfectly beneath it. Oh, I am still dreaming of this stove. Wak-wak!” “Does such a stove really look as beautiful as that?” asked the snowman. “Does it look like me?” “It is the very opposite of you. Black as a crow it is, and has a long neck with a brass top-piece. It eats fire-wood so that it spits fire out of its mouth. One must keep close to its side and it is very pleasant being quite under it. You can see it through the window from the spot where you are standing.” The snowman took a look at it. and noticed a black bright object with a brass top-piece upon it. The fire shone forth in front. A strange mood came over the snowman, a feeling seized him that made him wonder what it was. He could not account for it, but all men, unless they are snowmen know it. “Why did you leave her after all?” asked the snowman. He had a feeling that it must be a female creature. “How could you give up a post like this?” “I could not help it,” said the watch-dog. “I was turned out of doors, and chained up here because I had bitten the youngest squire’s leg for his kicking the bone at which I was gnawing. Bone for bone is my slogan. That was taken amiss a great deal, and from this time I have been fastened to the chain and have lost my voice little by little. I say, how hoarse I have got: Wak-wak! That was the end of the matter!” The snowman, however, did not listen any longer. He went on peeping at the housekeeper’s ground-floor and looked into the room where the stove stood on its four iron legs as tall as himself. “What a strange cracking all over my body,” said he. “Shall I never get into that house yonder’? It is only a harmless wish, and all our harmless wishes might be complied with after all. I cannot help wanting to go there, and I must lean against her even if I have to break the window-panes!” “Never will you get into the house yonder.” said the watchdog, “but when you come too near the stove, you will melt away, wak-wak!” “It is nearly all over with me!” replied the snowman. “I think, I am breaking down!” All day, the snowman peeped through the window, and when dusk came on, the room grew more tempting still. The fire of the stove shone forth so pleasantly, not in the least like the light of the moon nor that of the sun. The blazing up was altogether like that of a stove, when it has something in it. Whenever the door of the room opened, the flames leapt up from its mouth, such was the habit of the stove, Then the snowman’s white face flashed up red, and he blushed crimson to the heart. “I can’t stand it any longer!” said he. “How becoming it is to her, when she sticks out her tongue!” The night was long, but the snowman did not feel dull. He stood there, deeply absorbed in his own good thoughts, which were freezing up so that there was a cracking about them. In the morning, the window-panes of the ground-floor were covered all over with ice. They had the prettiest flowers of ice that a snowman can ever wish for, but they hid the stove. The panes would not melt, and so he was unable to see her whom he liked so much. There was a cracking and splitting in and round about him. It was just the frosty weather in which a snowman must take great delight. But he felt not happy — how could he do so after all, for he was longing so much for the stove. “That is a bad disease for a snowman.” said the watch-dog, “I, too, had been suffering from it, but I have got it over. Wak-wak.” he barked. “We shall have a change of weather.” And the weather did change. It began thawing. The thawing grew stronger and stronger. the snowman got thinner and thinner. He said no word, he did not complain, and this is the right omen. One morning he collapsed. And behold! Something like a broomstick arose at the spot where he had stood. The boys had built him up round the stick. “Well, now I see why he was overcome by his longing,” said the watch-dog. The snowman had a stove-scraper in his body. That’s what had been alive in him, Now all this has come to an end: wak-wak.” And before

long, the winter,

too, was over,

“Wak-wak,” barked the hoarse watch-dog at his

chain, but the little girls of the house sang:

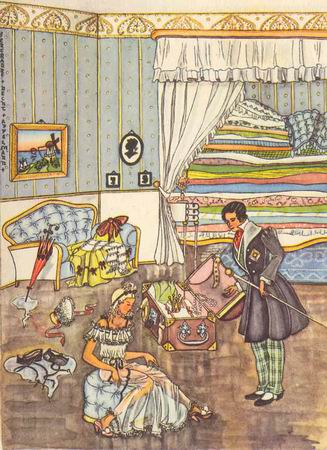

There was once a time a Prince who wanted to wed a Princess, but she should be a real Princess. So he travelled about all over the world to find such a Princess, but everywhere there was something in the way. Princesses there were in plenty, but whether they were real Princesses, he could not make out, as there was always something that was not quite in order about them. Therefore, he came home again and was quite sad. for he longed so much for a real Princess. One evening, a heavy storm arose, it thundered and lightened, and the rain poured down; it was quite frightful. There was then a knocking at the town gate, and the old King went to open it. It was a Princess standing outside at the gate. But alas! what a state she was in because of the rain and the terrible storm. The water ran down from her hair and her clothes, in at the top of her shoes and out at the heels. But she said that she was a real Princess. “Well, we shall soon learn it.” thought the old Queen. but without saying one word. She went into the bedroom, took all the sheets off the bed and laid a pea on the bottom of the bedstead. Then she took twenty mattresses, laid them on the pea and finally placed twenty more eider—down quilts on top of the mattresses. On the top of all these, the Princess was to lie all night. In the morning she was asked how she had slept. “Oh, terribly badly,” said the Princess. “Not a wink have I slept the whole night. Heaven knows what there must have been in the bed! I lay on something very hard so that I am black and blue all over my body! It is quite horrible!” Now, they saw well that she was a real Princess, as she had felt the pea through twenty mattresses and twenty eider-down quilts. Nobody but a real Princess could be so sensitive. So the Prince took her for his wife, for now he knew that he had a real Princess, and the pea was put into a cabinet of curiosities, where it is still if no one has taken it away. You see this is a true story!

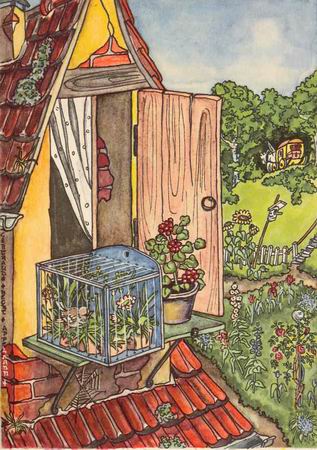

I say, now listen to me! Far away, out in the country, close by the road side, there stood a cottage. which you have surely noticed yourself some time. In front of it lay a small garden with flowers and fence around it. Nearby, beside the ditch, amidst the finest green grass, there grew a little daisy. The sun cast his rays as warmly and brightly upon it as he did with the big and gorgeous flowers within the garden, and thus it grew up from hour to hour. One morning it stood there, full-blown with its small white petals encircling like rays the tiny yellow sun in the middle. It did not occur to the daisy that nobody would notice it in the grass, and that it was a poor humble flower; nay, it was cheerful and turned straight towards the warm sun. Then it looked up to him listening to the lark which warbled in the air. The little daisy was as happy as though it had been a great holiday, and yet it was only Monday. All the children were at school. While they were sitting on their forms and learning something, it sat on its tiny green stalk and also learned from the warm-shining sun and from all round about how good God is. It became happy to hear that the little lark, all that the flower sensed in the stillness, sang so clearly and beautifully. The daisy looked up in a kind of awe to the happy bird, which could sing and fly, but was not grieved in the least at being unable to do so itself. “I see and hear there.” it thought. “The sun shines upon me and the wind kisses me. Oh, what rich talents has Nature bestowed upon me!” There stood plenty of stiff, stately flowers in the garden, and the less sweet fragrance they spread the more they boasted. The sunflower puffed itself up with pride so as to be bigger than a rose, but it is not the size which matters so much! The tulips had the most beautiful hues, of which they were certainly conscious. They held up their heads that they might be seen better. They did not notice at all the little daisy outside the garden, but this one looked all the more at them, thinking, “how rich and beautiful they are!” “Oh, to be sure, the splendid bird does fly down to see them. Heaven be praised that I stand so close by, for now I am able to see the grand display!” And at these very thoughts, “Quirvitt,” the lark came flying along, but not to the tulips, nay, down she alighted onto the green grass by the poor daisy, that was so shocked for joy that it did not know in the least what to think. The little bird danced around it singing: “Oh, how soft the grass is! What a lovely little flower there is, with gold in its heart and silver on its robe!” The yellow dot in the daisy certainly looked like gold, and the small leaves round about sparkled silverly-white. Nobody can imagine the happiness the little daisy felt. The bird kissed it with her beak, carolled to it and soared again into the blue air. A quarter of an hour had surely passed, until the flower was able to reassure itself. Party abashed and yet inwardly rejoiced, it looked about for the other flowers in the garden. They had, no doubt, noticed the honour and happiness which it had received. They could not help understanding after all what joy this had been to it. But the tulips stood twice as stiff as previously, and then they were pointed and red in their faces, because they had been angry. The sunflowers were all big-headed, and it was good that they could not speak, for else the little daisy would have seriously been rebuked. The poor little flower could see well that they were not in a good mood, and it felt sore at heart. At the same time, a girl with a big, sharp, and shining knife appeared in the garden, and went directly to the tulips, cutting them off, one by one. “Pooh,” sighed the little daisy, “that was dreadful, now it is all over with them!” Thereupon, the girl with the tulips disappeared. The daisy was glad to stand outside in the grass, and to be but a little flower. It felt so grateful, and when the sun set, it folded up its petals, fell asleep and dreamt all night long of the sun and the little bird. The next morning, when the flower unfolded all its white petals, just like little arms happily again towards the air and the light, it recognized the bird’s voice. But melancholy lay in her song. No doubt, the poor lark had a good reason for it. She had been caught, and sat now in a cage close to the open window. She jubilated at her free and happy flying about, carolled of the young green corn in the field, and of the wonderful journey she was able to make on wing high into the air. The poor little bird was not in a good mood, she sat as a prisoner in her cage. The little daisy wished to help her. But how to set about? Truly, it was hard to imagine. It wholly forgot, how beautifully everything stood around, and how warmly the sun was shining. Alas! It could do nothing but think of the captive bird, which it could not help. At the same time, two boys came out of the garden. One of them had a knife in his hands, long and sharp like that of the girl who had cut off the tulips. They walked directly towards the little daisy which could not understand what they intended to do. “There, we can cut out a nice grass-plot for the lark,” said one of the boys. Then he began cutting out a deep and four-sided piece of lawn round the daisy, so that it was standing in the midst of it. “Break the flower off!” said one of the boys, and the daisy trembled with fear. For, to be broken off, was like losing one’s life, and it loved life so much, just now that it should come into the cage to the captive lark. “No, leave it alone!” said the other boy, “it is such a lovely decoration.” And thus little daisy remained unhurt and was put into the cage with the lark. The poor bird, however, loudly poured out her grief about her lost freedom, striking her wings against the iron-bars of the cage. The little daisy was unable to speak, could not say a word of comfort, gladly though it would have liked to do so. Then the whole morning passed away. “Here is no water,” said the captive lark. “They have all gone out and have forgotten to give me a drop to drink. My throat is parched and burns. There is fire and ice in my body, and the air so sultry! Alas! I must be dying, I must part with the warm sunshine, the fresh green, with all the delightful things which God has created!” And then she bored her beak into the cool patch of grass to refresh herself a bit with it. Then she cast her looks at the daisy, nodded to it, and kissed it with her beak, saying: “You, too, must wither herein, you pour little flower! They have given me you and the tiny green grass-plot for all the world that I possessed outside! Let each little grass-blade be a green tree, each of your white petals a sweet-smelling flower to me! Alas! you just tell me, what loss I have suffered! “If only there were anyone that could comfort her!” thought the daisy, but it could not move one leaf. The fragrance, however, that streamed out of the delicate petals, was by far stronger than found elsewhere with this flower. The bird noticed it, and, although she was nearly parched with thirst and tore off with pain the green grassblades, she did not touch the flower. Evening drew near, and still nobody came to bring the poor bird a drop of water. Then she spread out her pretty wings shaking them convulsively, and her song became a woeful “peep, peep.” Then her little head bent towards the flower, and the bird’s heart was broken for want and longing. Now, the flower was unable to fold up its petals and go to sleep as it had done on the preceding evening. It drooped its head down to the soil, sickly and sadly. The boys did not come until the next morning, and beholding the dead bird, they wept bitterly and dug a neat grave for her, which was decorated with petals of flowers. They put the bird’s dead body in a beautiful red box, for they wanted to bury her in a kingly manner. So long as she was alive, they had forgotten her, let her sit in the cage and suffer from privation. Now she received a grand burial and plenty of tears. The plot of lawn, however, with the daisy was cast away. Nobody remembered the humble flower, which had most felt for the little bird and had wanted so much to comfort her.

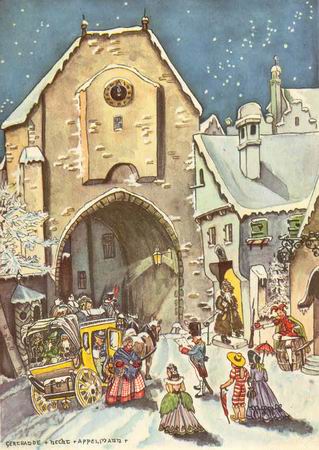

It was biting cold with a star-bright sky and not a breath of air stirred. “Bang!” Then an old pot was flung against the neighbour’s door. “Bang, crash!” There were loud gun reports to hear, salutes of honour were given by the people. It was New Year’s Eve! Now the church-clock was striking twelve! “Tarantara!” The mail-coach came driving along. The big carriage stopped in front of the town-gate. Twelve persons sat inside, all seats were taken. “Hurrah! hurrah!” shouted the people in the houses of the town, where New Year’s Eve was celebrated, giving three cheers on the stroke of twelve. They rose from their seats with filled glasses to welcome the New Year. “To your health,” somebody called, “a beautiful wife! A lot of money, no anger and worry may it bring you!” That was everyone’s wish, and upon it they touched the glasses so that they tinkled and rang — and in front of the town-gate stood the mail-coach with its strange guests, the twelve travellers. And who were these strangers? Each one of them had his passport and his luggage with him, nay, they even brought some gifts for you and me and all the people of the town. Who were they, what did they want, and what did they bring? “Good morning,” they called to the sentry at the entrance of the town-gate. “Good morning,” answered the latter, for the clock had already struck twelve. “Your name? Your occupation?” asked the sentry of one of them who first got out of the coach. “Go and look it up in my passport yourself,” answered this man. “I am I!” And a fine fellow he was indeed, clothed in bearskin and fur boots. “I am the man in whom a great many people put their trust. See me tomorrow, then I shall give you a New Year’s gift. “I throw pennies and shillings among the people, nay, I shall hold dancing-parties, thirty-one parties exactly, but any more nights I cannot waste. My ships are frozen up, but it is warm and cosy in my office. I am a merchant, my name is January, and I am carrying only bills about me.” Then the second got out of the coach, and this one was a jolly old fellow! He was a playhouse manager, the promotor of masked balls and of all sorts of entertainments imaginable. His luggage consisted of a huge tun. “At the time of carnival,” he said, “we are going to drive the cat out of the tun. I shall certainly be giving you pleasure enough and not forget either myself. All days merry making! I can’t say that I may live for long, of the whole family I live the shortest time. I will not make old bones, but twenty-eight days, to wit. Now and then, they incorporate another day — but I don’t care much about it. hurrah!” “You must not shout like that,” said the sentry. “Why, of course, I may shout,” called the man. “I am Prince Carnival, travelling about, and known as Februarius.” Now the third got out of the coach. He looked like the personified fasting, however he carried his nose in the air, because he was akin to the “forty knights,” and besides he was a weather-prophet. But this is no rich post, and so he praised the Lent as well. He wore a tiny bunch of violets in his button-hole. But those were very small. “March! March!”, called the fourth to him, tapping on his shoulder. Do you not smell anything? Make haste to get into the guardroom! They are drinking punch there, your favourite arid refreshing beverage. 1 am already smelling it here! Forward! march! Mr. Martius!” — But this was only a lie, he just wanted to make him feel the importance of his name, to make an April fool of him. Therewith the fourth started his earthly career in the town. He had, no doubt, a dashing appearance; he did but little work, the more so he was fond of holidaymaking! “Suppose we had greater stability in the world,” said he, “but one is soon in a good temper soon in a bad one according to the circumstances: soon it rains, soon is sunshine Moving in and out! I, too, am such a kind of lodging-house-keeper, I am able to laugh or to cry. as the case may be. In this trunk is my summer clothing. but it would be foolish to put it on. Well, here I am! On Sundays I am in the habit of walking about in shoes, wearing white silk stockings and a muff! After him a lady alighted from the coach. She was named Miss May. She wore a summer costume and galoshes, a lime-leaf coloured frock. Windflowers stuck in her hair, arid there was such an intensive perfume of woodruff about her that the sentry could not help sneezing. “God help and bless you!” said she, this was her greeting. What a graceful creature she was! And a songstress she was, not a stage one, nor a street one, but a singer of the wood. She would roam about in the fresh green wood singing here for her pleasure. “Now comes the young lady,” they cried in the coach, and out got the young lady, fashionable, proud, and neat in her appearance. Her behaviour showed that she, Mrs. June, was accustomed to be waited upon by the lazy Seven Sleepers. On the longest day of the year, she would give great parties so that the guests might hate time enough to eat the many dishes at table. She had, it is true, a carriage of her own, yet she travelled by mail-coach like the others, to show that she was not haughty. However, she was never without a companion, for her younger brother was always with her. He was a well-fed fellow, dressed in summer-fashion and wearing a Panama hat. He carried with him but small luggage, because it was too troublesome during the great heat. Therefore, he had provided himself with only a bathing suit, and this is really not much. Thereupon came the mother herself, Dame August, wholesale in fruit. She owned a number of fish-ponds, was stout and hot, lent a hand everywhere, and carried to the fields, with her own hands, the beer for the labourers. “In the sweat of thy brow thou shalt eat thy bread!” she said, “these words are from the Bible.” Afterwards come the carriage-rides, dancing and entertainments, and the harvest feasts. “She was an excellent housekeeper.” After her, another man alighted from the coach, a painter, Mr. September, master-dyer by trade. He belonged to the wood. The leaves had to change their colouring. How nice, whenever he wanted to! And before long, the wood lay in a variety of hues, having a reddish, yellow, or brown tinge. The master whistled like the black starling, was like a brisk workman and wreathed the blue-green hop-vine round his beer-jug. That decorated the jug, and he had just a liking for such trimmings. There he stood with his paint-pot which was all his luggage! He was followed by the freeholder, who always thought of the month of seed, ploughing and tilling the soil, as well as of the pleasures of going out hunting. Mr. October carried his dog and gun with him, and had nuts in his hunting-bag, “click, crack!” He had plenty of luggage with him, even an English plough. He talked about agriculture, but only little was understandable on account of his neighbour’s coughing and moaning. — It was November who was coughing like that, while he was leaving his coach. He was much afflicted with a cold in his nose, and unceasingly blew his nose. Yet, he said, he was bound to accompany the maid-servants and introduce them into their new winter-services. He thought that the cold would be soon over, when he set to work wood-cutting, and he would have to saw wood and to chop it, for he was master-sawer of the wood-cutting guild. Finally, the last traveller made her appearance, little Granny December with her portable stove. The Old one shivered with cold, but her eyes sparkled like two bright stars. She carried a flower-pot, wherein a little fir-tree was planted, in her arms... “I will nurse and foster this tree tenderly, so that it may thrive and grow on till Christmas Eve. And it must reach from the floor up to the ceiling, shooting up with blazing lights, golden apples, and tiny-carved figures. The portable stove is as good as real one. I take the book of Fairy Tales out of my pocket, and read aloud from it. Then all the children in the room keep still, the little figures on the tree, however, come to life, the little angel of wax sitting on the top of the tree, spreads out his leaf-gold wings, and flies down from his green seat. Then he kisses both great and small in the room, nay even the poor children, as they stand in the entrance-hall and in the street, and sing the Christmas Carol of the Star of Bethlehem.” “Well, all right, now the coach can start,” said the sentry, “we have all twelve of them. Let the extra coach drive up!” “Do let the twelve enter my room first!” said the commander of the guard, “one by one!” I keep the passports here, they are each valid for a month. When its time is up, I shall certify the behaviour in the passport. Mr. January, pray, do step nearer!” And Mr. January stepped nearer. And when a year has passed away, I am going to tell you what the twelve have brought to all of us. At present I don’t know, and they certainly don’t know it either — for it is a remarkably uneasy time we live in.

|