| 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to Fairy Tales Content Page |

(HOME) |

| 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to Fairy Tales Content Page |

(HOME) |

|

There was once upon a time a poor Prince. He possessed only a tiny kingdom which, however, was big enough. after all, to allow him to get married, and this he was ever so eager to do. Now, to be sure, it was somewhat bold of him that he ventured to say to the Emperor’s daughter: “Will you have me?” But he did so, for his name was noted far and wide, and there were more than a hundred princesses who would fain have said “Yes” with all their hearts, but I wonder whether she would? Well, let us hear about it! A rose-bush grew on the grave of the Prince’s father, a wonderful rose-tree. It bloomed, however, only every fifth year, and then bore but one flower. This was a rose that had so sweet a perfume that everybody forgot all his sorrows and his grief, whenever he smelt it. The Prince also had a nightingale which could sing so beautifully, as though all lovely melodies stuck in her throat. This rose and this nightingale were meant for the Princess, and so both were placed into big silver cases and sent to her. The Emperor ordered his attendants to carry them before him into the large hail, where the Princess was playing at “visiting” with her ladies-in-waiting. On beholding the big cases with the presents therein, she clapped her hands with joy. “If it only were a little pussy-cat,” said she. But forth came the rose-bush with the lovely rose. “How neatly

it is

made!” said all the

ladies-in-waiting. “It is more than neat,” said the Emperor, “it is beautiful!” But the Princess touched it, and then she was ready to weep. “Fie, daddy!” said she, “it is not an artificial one, it is a real one.” “Fie,” said the ladies-in-waiting, “it is a real one!” “Well, let us first see, what there is in the other case before we get angry,” said the Emperor, and forth came the nightingale. which sang so beautifully that at first nobody could utter anything evil against it. “Superbe, charmant!” said the ladies-in-waiting, for they all talked French, the one always worse than the other. “How this bird reminds me of the musical box of our lamented Empress!” said an old courtier. “Ah, yes. they are the same airs, the same presentation.” “Oh yes,” said the Emperor, and burst into tears like a little baby. “I won’t

hope it might be a real one,”

said the Princess. “Yes, it is a real bird,” said the messengers who had brought it. “Well, let the bird fly away!” said the Princess, and she would not allow the Prince to come. But the latter was not so easily frightened away. He stained his face brown and black, pulled his cap over his eyes. And knocked at the door. “Good morning. Emperor,” said he. “Could I not enter into Your Majesty’s service at this castle?” “Oh yes,” said the Emperor. “I want somebody to tend the pigs, of which we have plenty.” So the Prince was appointed imperial swineherd. He got an awfully small chamber down near the pigsty, and here he had to stay. But he sat there working all day long, and when evening came, he had made a neat little cooking-pot. Round it there were bells, and as soon as the pot boiled, they tinkled and played a beautiful melody: “Oh,

my dear

Augustin. what is to be done. But the most cunningly devised feature was that by holding one’s finger in the steam of the pot, one could smell at once what kind of food was being cooked at every hearth in the town. This was indeed quite a different thing from a rose! Now, the Princess came sauntering along with all her ladies-in-waiting, and on hearing the air, she paused and looked entirely rejoiced, because she, too, could play: “Oh, my dear Augustin.” It was the only air she knew, and she played it with one finger only. “That’s just the air that I know,” she said, “Then he must be a well-bred swineherd! I say go down and ask him what this instrument costs!” So, one of the maids of honour had to go down, but she put on wooden clogs. “What will you have for the pot,” asked the lady. “Ten kisses from the Princess,” said the swineherd. “Heaven preserve us!” said the maid. “Yes, I won’t take less!” answered the swineherd. “He is shocking,” said the Princess, and then she went away. But when she had walked a little way, the bells tinkled so beautifully: “Oh,

my dear Augustin, what is to be done, “I say,” said the Princess. “go and ask him. whether he will accept ten kisses from my ladies-in-waiting!” “No, thank you so much,” said the swineherd. “Ten kisses from the Princess, or I keep my pot!” “What a tiresome business that is!” said the Princess. “But then you must stand before me so that nobody may watch what I do!” The maids of honour lined up around her and spread out their skirts, and then the swineherd got his ten kisses and the pot was hers. Why, this was indeed a delight to all! The pot had to boil the whole evening and all day. There was not a single fire-place in the whole town without their knowing what was being cooked on it, both at the chamberlain’s and the cobbler’s. The ladies-in-waiting danced and clapped their hands. “We know who is eating sweet soups and pancakes and we know who gets groats and roast meat. How nice it is!” “Yes, but hold your tongue, for I am the Emperor’s daughter!” “Certainly, certainly,” they all said. The swineherd, that is to say, the Prince — but they only knew him as a swineherd — did not idle away his time without doing something. So, he made a rattle, and when this was swung around, all the waltzes and galops, which were known since the creation of the world, were heard, “Oh, that is superbe!” said the Princess passing by. I have never heard more beautiful music! “I say, go and ask him, what the instrument costs, but I won’t kiss him again!” “He wants a hundred kisses from the Princess,” said the lady-in-waiting, who went to ask. “I think he is a fool!” said the Princess, and then went away. But when she had walked only a little way, she stopped. “One must encourage art,” said she. “I am the Emperor’s daughter. Tell him he is to have ten kisses as the other day. He can take the rest from my ladies-in-waiting!” “Oh, we don’t like that at all,” said the ladies. “That is rubbish.” said the Princess. if I can kiss him, you can do so as well! Mind, I give you board and lodging!” So, the ladies-in-waiting had to go to him once more. “A hundred kisses from the Princess,” said he, “or each one may keen his own.” “Stand in front of me!” said she, and whilst all the maids took their stand before her, he kissed her. “I wonder what that crowd near the pigsties may mean?” asked the Emperor. who had stepped out onto the balcony. He rubbed his eyes and put on his spectacles. “Behold! they are the ladies-in-waiting, making so much fuss. I think I must go down and see after all!” My goodness, what a hurry he was in! As soon as he got into the yard, he trod quite softly. The maids were so busy counting all the kisses, so that it should be a fair deal. that they did not notice the Emperor at all. He raised himself on tiptoe. “What’s the meaning of that?” said he, on seeing the two kissing, and then he struck his daughter on her head with a slipper at the very moment when the swineherd got his eighty-sixth kiss. “Off with you!” said the Emperor, for he was angry, and both the Princess and the Swineherd had to leave his realm. There she stood weeping, the swineherd scolded, and the rain poured down. “Oh, what a miserable creature I am,” said the Princess, “would I had accepted the handsome Prince! Alas! how unhappy I am!” The swineherd, however, went behind a tree, wiped the black and brown stain from his face, and cast away his nasty clothes. Then he stepped forth in his princely robes, and he looked so handsome that the Princess could not forbear curtsying to him. “I am come to despise you,” said he. “You would not have an honourable prince, You would not appreciate the rose and the nightingale, but you did not mind kissing a swineherd for a trumpery musical-box. That’s now your reward!” Then he went back into his kingdom. And she was left alone singing: “Oh,

my

dear

Augustin, what is to be done,

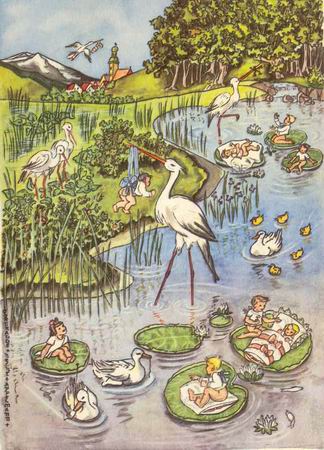

On the last house of a small village there was a stork’s nest. The mother stork was sitting in it with her four little ones, who stuck out their heads with the little black beaks which had not yet grown red. A little distance off, father stork stood on the ridge of the roof, upright and stiff; he had drawn one leg up under him in order to have at least some trouble while standing sentry. One might almost have thought that he was carved out of wood, so still did he stand. ‘‘It will no doubt look very dignified for my wife to have a sentry on guard by the nest,” he thought. “They cannot know that I am her husband, they are sure to believe I have been ordered to stand here. It looks very fashionable!” And he kept on standing on but one leg. Down in the street, a number of children were playing, and catching sight of the storks, one of the boldest boy, and afterwards all of them together, sang a verse from the old song about the storks: “It’s

time,

father stork, to get to thy nest: “Just listen, what the children are singing,” said the little storks. “They sing we are to be hanged and burnt!” “You should not bother your heads,” said the mother stork. “Don’t listen to them then there will be no harm in it at all!” The boys, however, went on singing, and they teased the stork pointing at him with their fingers. Only one boy, named Peter, said that it was wrong to make fun of animals, and so he would not take any part in it. The mother stork comforted her little ones: “Don’t trouble yourselves about it,” she said, “just see, how steadfastly your father stands, and this on but one leg!” “We are so much afraid,” said the young storks, drawing back their heads into the nest. The next day, when the children met again and beheld the storks, they began singing their verse: “One

of them, alas! they want to hang “Are we to be hanged and burnt?” asked the young storks. “No, certainly not,” said the mother. You shall learn how to fly. I will drill you well to do so! Then we will fly out into the meadows and pay a visit to the frogs. They will bow to us in the water singing “Koax, koax,” — and then we eat them all up. That will give us a real treat!” “And what next,” asked the young ones. “Then all the storks of the whole country assemble, and the autumn training will start. Everyone of you must become a good flier, which is of great importance; for, the one who cannot fly well, will be run through the body to death by the colonel’s beak. Pay, therefore, good attention to learn something, when the training begins!” “After all then, we shall be staked just as the boys said – and do listen how they are singing it once more!” “Listen to me, and not to them,” said the mother stork. “After the great field operation in the autumn, we shall fly away to the warmer countries, far, far from here. over the woods and mountains, To Egypt do we fly, where people live in stone homes with three-cornered sides, ending in a point and towering above the clouds, They are called pyramids, and are older than any stork can imagine. Moreover, there is a river there that overflows its banks thus turning all the land to mud. You walk about in the mud eating frogs.” “Oh!” said all the young ones. “Yes, that will be a thrilling thing! You need do nothing but eat all day long, and while we are enjoying a jolly time, there is no green leaf on the trees in this country. Here it is so cold that all the clouds freeze to pieces and fall down in tiny white flakes.” She meant snow by that, but was unable to explain it better. “Do the naughty boys also freeze to pieces?” asked the young storks. “No, they don’t freeze to pieces, but they come near it and must sit as sneakers in the sombre rooms, But you can fly about in the foreign country where there are flowers and the warm sun shines.” Now, a good while had passed, and the young ones had grown so tall that they could stand upright in their nest, and look about near and wide. The father stork came flying every day with fine frogs, little snakes, and all sorts of delicacies he could find. Oh, what a fun to watch the tricks he did! He turned his head right around on to his tail, clattering with his beak as if it were a little rattle. Then he told them stories about the swamp. “I say, now you must learn to fly,” said the mother stork one day. and now all the four young ones had to go outside on to the ridge of the roof. Oh. how they staggered and kept their balance with their wings, and yet were near falling down! “Now, just look at me!” said the mother. “You have to bear your heads and put your feet like this! One! Two! That’s what is to get you along in the world!” Then she flew a bit of the way off, and the young ones made a little awkward jump. Flop! There they lay, for their bodies were too clumsy. “I don’t want to fly,” said one of the young storks, and crept into the nest again! “I don’t hanker for going to the warm countries.” “Do you want to freeze to death when the winter draws near? Shall the boys come to hang, to burn, or to stake you? Well. I will call them!” “Oh no,” said the young stork, hopping on to the roof again like the others. By the third day, they were already able to fly a short way fairly well, and they thought they could hover and rest in the air too. That’s what they wanted to do, but —flop! — they turned a somersault and had therefore to move their wings fast again. Down in the street the boys now reappeared singing their usual song: “It’s time, father stork, to get to your nest!” “Shall we not fly down and frighten them away?” asked the little ones. “No, leave them alone,” said their mother. “Just listen to me, that is by far more important! One, two, three! Now we are flying to the right. One, two, three! Now to the left and round the chimney! Behold! That was very good. The last stroke of the wings was so skilful and correct that you may fly with me to the swamps tomorrow. There you will find several pretty families with their children; now let me see that mine are the cleverest and you are strutting along well. It looks well and gives you an air of credit!” “But are we not to punish the naughty boys?” asked the young storks, “Let them shout as much as they like! You will soar up to the clouds, though, and get to the land of the pyramids, whereas they will be cold with no green leaf nor a sweet apple for them.” “Well, but we will take our revenge on them all the same,” they whispered to one another, and then their drilling began anew. Of all the boys in the street was not one worse to sing the mocking song than a tiny little fellow, who was presumably not more than 6 years old. It ist true that the young storks believed he was at least a hundred, because he was so much taller than their father and mother, And what did they know about how old children and grown-up people could be? This boy was to receive his well deserved punishment, as he had first begun to tease them, and he went on doing so. The young storks were awfully cross, and as they grew older, they could stand it still less. At length, their mother had to promise them to punish him, but no sooner than the last day they stayed in this land. “Above all we must see how you will behave at the great field-days. If you stand this test badly and the colonel runs you through the breast with his beak, then the boys will surely be right, at least in one respect! Now let us see!” “Certainly, that you shall do,” said the young ones, and so they took every pains possible. They practised every day and flew so nicely and lightly that it was quite a pleasure to look on. Then came the autumn. All the storks began to assemble in order to migrate to the warm countries while we have wintertime. What a fun that was! They had to fly over woods and villages only to show how they could fly now; for it was certainly a great journey which was ahead of them. The young storks did their tasks so well that they got “excellent marks in the form of frogs and snakes.” Thus, they had the very best characters, and they could eat the frogs and the snakes to their hearts’ content. Believe me, they did so! “Now let us punish him,” they said. “Yes, certainly,” said the mother bird. “The plan I have devised, is just the right one! I know the pond-where all the little human babies lie, until the stork comes to take them to their parents. The prettiest tiny babies are there asleep dreaming so beautifully as they will do nevermore in later life. All parents like to own such a little one. and every child wants a baby sister or brother. Now let us fly to the pond, to fetch one for each of those children who did not sing the evil song or make fun of the storks!” “But what shall we do with that naughty, wicked boy who first began singing,” called the young storks. “No baby boy nor little sister do we fetch for him out of the pond, and then he must weep for standing out as being alone! But you have surely not forgotten the good-natured boy, the one who said it is a sin to make fun of the animals? We will bring him a brother as well as a sister, and because his name is Peter, you shall be called Peter too!” And it happened just as she said, and all the storks were and are called Peter to this very day.

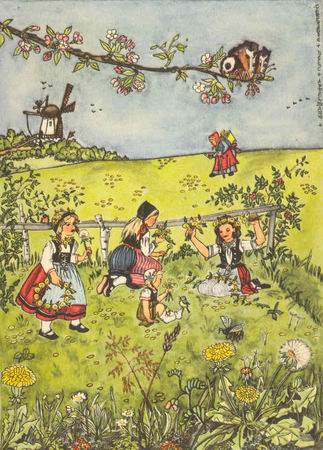

It was in the month of May, and the wind was still blowing cold. But “spring is come,” said bushes and trees, fields and meadows, and the whole land was covered with plenty of flowers reaching high up to the living hedges. It was there that the spring conducted his own cause. He reached down from a small apple-tree, where a single twig hung fresh and in bloom, sprinkled all over with delicate pink-coloured buds, about to burst open. It knew very well how fine it was, for there is something peculiar within both the leaf and the blood. So, it was not surprised to see a lady’s private carriage stopping before it, and the young countess thought an apple-twig to be the most lovely thing imaginable: It would be like Spring himself in his grand manifestation. She broke the twig off, and took it in her graceful hand, shadowing it with her silk sunshade. Then they drove to the castle with its lofty halls and gorgeous rooms. Bright and white curtains before the open windows were flying about in the wind, shining and transparent vases with delightful flowers stood there. And the apple-twig was put into one of them, looking as if formed from new fallen snow, between fresh, light beech-twigs. It was a delight to see it. Now the twig became proud. All sorts of people passed through the rooms, and in accordance with the esteem they enjoyed, they were allowed to express their admiration. Some of them did not say a word, others, however, talked too much. But the apple-twig understood that there must be a distinction among the plants. “There are some of them making a grand display, others are for nourishing. There are, too, such ones. which could be dispensed with altogether,” thought the apple-twig. And just standing before the open window, whence it could look into the garden and into the field, it had flowers and plants in plenty to watch and muse over. There stood rich and poor ones, a few of them even too poor. “Poor cast-out plants,” said the apple-twig, “certainly, there is some distinction.” How unhappily they must feel if this kind is able to feel in the same way like me and my equals. Of course, there is a distinction which must be made,or otherwise they all would be alike!” And the apple-twig sympathetically viewed in particular a kind of flowers of which there grew plenty in the fields and ditches. Nobody made up a nosegay of them, they seemed too common, nay, they were even to be found between the stone pavement. They shot up like the worst weeds and went by the ugly name of “Dog-flowers”. “Poor despised plant,” said the apple-twig, “it is not your fault that you got this ugly name. But as it is with men so it is with plants, some distinction must be.” “Distinction,” said the sunbeam kissing the blooming apple-twig and, at the same time the yellow dog-flowers, those out in the fields too. And all the brothers of the sunbeam kissed them, the poor flowers as well as the rich ones. The apple-twig had never pondered on God’s eternal love to all that is alive and astir in Him, and how many of the beautiful and good things there may be hidden but not forgotten. The sunbeam, the ray of light, knew it better: “You don’t see far, you don’t see your way clear! — Which is the most disdained weed that you pity above all?” “The dog-flower,” said the apple-twig. “Never is a nosegay made of it, it is trodden under foot. They are too numerous, and when they run to seed, they fly like small-cut wool-pieces across the way sticking to the people’s clothes. It is weed, but this must be after all!” — How thankful I am not to have become one of those flowers!” Now a band of children came across the field. The youngest of them was still so small as to be carried by the others. As it was placed into the grass among the yellow flowers, it burst out laughing for joy, kicking about with its little legs and rolling to and fro. Then it picked only the yellow flowers and kissed them in sweet innocence, The somewhat older children broke the flowers off the lofty stalks. They curved these round, link in link, so as to form a chain. There was at first one for their necks, then another to be hung round their shoulders and the body and yet another to fasten to their breasts and their heads. What a splendid show of green links and chains this was! However, the older children cautiously took the deflowered plant by its stalk which bore the pinnated combined seed-pods. This loose and gay woolbearing flower which is a genuine work of art, as if formed out of the lightest feathers, flocks, and downs, was held by them to their mouths. Then they tried to blow them off altogether at a time, and whoever was able to do so, got, as Grandmother would say, new clothes before a year has passed away. On this occasion, the disdained flower was like a prophet. “Do you see?” said the sunbeam. “Do you notice the beauty and the power?” “Certainly, for children only,” answered the apple-twig. And an old woman came into the field digging with the stub of a shaftless knife for the roots of the herbs, drawing them out. She wanted to make coffee with some of them, and, for others she would get money at the chemist’s. “Beauty is still somewhat grand, though,” said the apple-twig. Only God’s elect get into the realm of the beautiful! There is some distinction among the plants like that among men.” The sunbeam talked of the eternal love of God, revealing itself in the whole work of creation, and of all creatures endowed with life and the equal distribution of all the things in time and eternity. “Well, this is now your view,” said the apple-twig. People entered the room, and the beautiful young countess appeared. It was she who put the apple-twig into the transparent vase where the sunlight was shining, and she brought a flower along, or whatever it might be. The object was hidden away by three or four leaves, held around it in the form of a paper-bag so that neither a draught of air nor a gust of wind might do any harm to it. It was carried so cautiously as had never been the case with an apple-twig before. Then the big leaves were removed carefully, and the fine, well-built seed-pod of the yellow disdained dog-flower became visible. She had picked it so cautiously, so carefully, lest one of the fine feathered arrows, which form its nebulous shapes should be blown off. She carried it unhurt admiring its beautiful form, its airy clearness, its quite peculiar composition and its beauty, which thus should go with the wind. “Behold! How wonderfully lovely God has created it,” said she. “I will paint it together with the apple-twig, everyone finds it so immensely beautiful. This flower however, too, has received as much in beauty from our Heavenly Father. Different as they are, they are none the less both children in the realm of beauty.” — The sunbeam kissed the poor flower and the blossoming apple-twig, the leaves of which seemed to blush.

|