|

1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

THE TRIAL AND RENDITION OF ANTHONY BURNS

From a print.

“Anthony Burns,” by Charles Stevens.

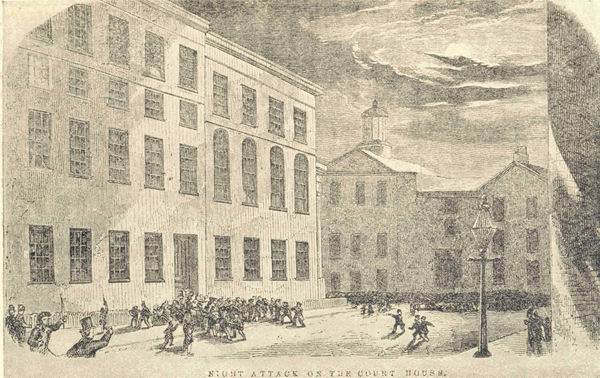

NIGHT ATTACK ON THE COURT HOUSE IN WHICH ANTHONY BURNS WAS TRIED.

So great was the interest in Anthony Burns that P. T. Barnum, the showman, offered him $500 after freedom had been given him, if he would tell his story on the platform for five weeks. The offer was promptly rejected. Burns’s extradition from Boston was the most memorable of the “fugitive slave” cases in New England. Great excitement was created, much expense entailed and serious questions of law were brought up. It was only a few years before that the fugitive Sims had been returned to the South, and another slave, Shadrach, had been arrested and finally escaped.

Burns came to Boston and found employment in a clothing store on Brattle Street. While leaving this shop on the 24th of May, 1854, he was arrested by a man named Butman, whose business it was to hunt fugitive slaves. Butman told him he was charged with theft. Six or seven other men then rushed out to assist in the capture, and they carried Burns to the Court House before the United States Marshal, E. G. Loring. Only now did it begin to dawn upon the unfortunate prisoner that he had been arrested as a fugitive slave or, even worse, as a runaway. In a few moments his former owner, Colonel Charles F. Suttle, and the latter’s agent, both from Alexandria, West Virginia, appeared, the former greeting the prisoner sarcastically as “Mr.” Burns. The Colonel asked him if he had not given him money when he needed it, to which Burns replied that he had always received from him twelve and a half cents once a year. During the night Burns was obliged to fast, in the mean time watching his armed guard of eight men indulging themselves in luxuries. After a small breakfast he had to appear in court. The papers knew nothing of his arrest, and it may have been the intention of the authorities to hold the examination and remove the prisoner before any rumors got abroad. It happened, however, that R. H. Dana, Jr., the well known lawyer, and author of “Two Years before the Mast,” was passing the Court House at the time set for the examination, and he went inside and offered his services to Burns, who replied, “It will be of no use: they have got me.”

The news of Burns’s arrest spread rapidly, though no active interest was taken except by the Vigilance Committee, which was composed of some of the best-known men of Boston. It was organized to assist slaves from falling into the grasp of the law, to rescue them, if possible, and to prevent slaveholders from recovering their lost property. This Vigilance Committee determined that Burns should never be taken back to Virginia. Several plans were discussed. It was decided that a public meeting should be held at Faneuil Hall, and seven men pledged themselves to leave the meeting and to attack the Court House in an attempt to rescue Burns. Notices in the papers, and placards, succeeded in filling the hall. Samuel E. Sewall called the people to order, and George R. Russell, ex-mayor of Roxbury, presided. Robert Morris, a colored lawyer, and Dr. Henry I. Bowditch, son of the mathematician, acted as secretaries. The presiding officer started his address by saying that it was the boast of the slaveholder that he would call the roll of his slaves on Bunker Hill. Wendell Phillips and Theodore Parker also made speeches, the latter declaring: “There is no Boston to-day. There was a Boston once. Now there is a north suburb to the city of Alexandria.” As he closed his remarks a roar burst forth, “To the Court House!” “To the Revere House for the slave-catchers!” It was moved to adjourn to Court Square, but only six of the seven pledgers turned up prepared to carry out their threat. Nothing daunted they collected some friends and numbering twenty-five began their attack on the Court House door, armed with revolvers, axes and butcher knives. A large piece of timber was used as a battering-ram, and chiefly through the courage and determination of the Rev. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, whose ancestry goes back to Governor Endicott, the door was forced. The people in the street in the mean time shouted encouragement, throwing stones and even shooting at the windows. In the attack one of the Marshal’s aides was killed. Mr. Higginson, much to his surprise, found himself alone inside the Court House in the midst of numerous soldiers. He yelled “Cowards!” to his friends, two of whom, Seth Webb, Jr., and Lewis Hayden, managed to squeeze their way in. Colonel Suttle in the mean while made a hasty exit by the east door, leaving his “property” to be defended by others. Burns’s keepers in the upper story gave up card-playing temporarily and crouched thoroughly frightened in the farther corner of the jury-room, which was used as a prison, it having been ruled that fugitives could not be confined in a Massachusetts jail. Both the State and the United States troops were called out to preserve order. As Mr. Higginson remarked, “It was one of the best plots that ever failed.” Steps were now taken to secure Burns’s release by legal process through the Writ of Personal Replevin, which demanded a verdict as to whether or not the prisoner was righteously restrained of his liberty. It was the opinion of Sewall and Bowditch that Burns should be taken out of the hands of the Government even if force were necessary. The anger of the people had now risen to such a pitch that Colonel Suttle moved into the attic and furnished himself with an armed guard. His sojourn in Boston was made even more miserable by four or five negroes who kept watch unceasingly beneath his windows with the special purpose of intimidating him. He finally became so alarmed that he decided to sell his slave, naming $1,200 as his price. The Rev. Mr. Grimes, pastor of a church for colored people and also of a church for fugitive slaves, both in Boston, came to the rescue, obtained the necessary funds, chiefly through the help of Hamilton Willis, a State Street broker, and attempted at a prearranged meeting with Colonel Suttle to put through the sale. The papers had been drawn, and even a carriage was at the door in which to remove Burns, when District Attorney Hallett objected on account of the Government’s expense in connection with the case. Another meeting was arranged, but only Mr. Grimes appeared and the question of sale had to be dropped.

The trial took place in the Court House, which was guarded like a fortress; firearms were pointed out of the windows, all entrances except one were guarded, and only persons known to be favorable to the Government’s cause were allowed in, even Mr. Dana himself being refused admission for a long time. C. E. Stevens, who wrote a history of Anthony Burns, said that “never before, in the history of Massachusetts, had the avenues to a tribunal of justice been so obstructed by bayonets.” The prisoner was guarded by seven or eight hard-looking characters with pistols only half concealed from the spectators. Burns’s counsel, Ellis and Dana, objected to the arms, but were overruled by the Court. Dana in his remarks said that the slums of the city had never been so safe as all the scoundrels in Boston were in the Court Room. He was assaulted and knocked down some days later for these violent words. The family has a large tray which was given to Mr. Dana for his services; also the family possesses the original piece of paper from which he made his address.

Contrary to the popular belief that the verdict would be favorable to the prisoner, the Judge ruled that he should be returned to his master. How to accomplish this was the next consideration. General Edwards was chosen to command the troops. He assembled them on the Common, supplied each man with eleven rounds of ammunition and took care to have each one load his gun in the presence of the spectators. Burns was marched down State Street guarded by three battalions of infantry, the 5th Regiment of Artillery and the Corps of Cadets, while the bystanders groaned and hissed. Many windows were draped in black, one near the Old State House having hung from it a black coffin with the words “The Funeral of Liberty” on it, and farther on was suspended across the street an American flag draped in black and Union down. Many of the troops drank heavily before the day was over, and towards afternoon some were found singing a chorus of “Oh, carry me back to Old Virginny.”

After Burns’s embarkation effigies were burned throughout New England for many days. A steamer at Long Wharf conveyed the unfortunate negro back to a traders’ jail in Richmond, where his hands were handcuffed behind his back most of the time. He remained there for four months, the “Boston lion,” as he was called, offering amusement for the hundreds of people who came to see him. He was removed from prison and sold by Colonel Suttle for $905, and later his freedom was purchased by Mr. Grimes for $1,300. He returned to Boston and spoke at Tremont Temple and many other places. He spoke well, for he had received a good education and had been approved in the South as a minister to preach to the colored people.

A Southern editor wrote, “We rejoice in the capture of Burns, but a few more such victories and the South is undone.” Burns was the last slave returned.

Dr. Bowditch described the society now formed, called the Anti-Man Hunting League, which actually practised kidnapping one of its members in order to learn how really to do it should the occasion arise.