|

1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

SOME CURIOUS OLD NEW ENGLAND CUSTOMS

A survey of the lives of the early Puritans reveals many quaint and curious customs. The life of a New Englander, particularly of a woman, was very strict, and special attention was given to grace and carriage. A piece of poetry written by Oliver Wendell Holmes well illustrates the care given to the woman’s appearance:—

“They braced my aunt

against a board

To make her straight and tall.

They laced her up, they starved her down,

To make her light and small.

They pinched her feet, they singed her hair,

They screwed it up with pins.

Oh! never mortal suffered more

In penance for her sins.”

To remain long unmarried was considered deplorable and it has been said of the colonists that “they married early and they married often.” A woman was considered an old maid at twenty-five. Widowers and widows remarried as soon as possible, the record undoubtedly being held by the wife of a certain Governor of New Hampshire who was a widow only ten days. Bachelors were scarce and were looked upon with much disfavor. In Hartford, “lone-men,” as they were sometimes called, had to pay twenty shillings a week to the town for the selfish luxury of living alone. One of the most amusing laws was passed by the town of Eastham, Massachusetts, in 1695, the vote reading that “Every unmarried man in the township shall kill six blackbirds or three crows (every year) while he remains single; as a penalty for not doing it, shall not be married until he obey this order.” A bachelor was constantly under the supervision of the constables and the watchmen and therefore actually gained rather than lost his freedom by marrying. The unmarried men of some towns were encouraged to marry by being offered plots of land on which to build, upon marrying. It is said that in Medfield, Massachusetts, there was a street called Bachelors’ Row, which had in this way been assigned.

Love-making in Boston was often carried on in the Common, one writer stating that “On the South there is a small but pleasant Common where the gallants, a little before sunset, walk with their Marmalet-Madams till the nine o’clock bell rings them home to their respective habitations.” From the above it seems that the New Englander kept early hours. John Quincy Adams also mentioned nine o’clock as the customary retiring hour in Quincy, following his remark by stating that if one were dining out and stayed after this hour one’s horse invariably walked home alone. A curious custom concerning love-making was that the lover must first gain the consent of the girl’s parents, who, however, having once given permission, could not retract. Court records show that parents were often sued for endeavoring to end a sanctioned love affair. One record shows that a lover sued the girl’s father for the loss of time spent in courting. The “coming out” or “walking out” of the bride was an important event in the community. This meant that the newly married couple appeared together often in public, led small processions of people to church, and took prominent seats in the gallery. Often in the middle of the service the bridal couple would rise and slowly turn around several times in order to attract the attention of their friends in the congregation. It is a curious fact that a magistrate, a captain, or even a prominent man in the community could perform the marriage service, but that a parson could not do so,—not until the beginning of the eighteenth century. Governor Bellingham actually performed the marriage service over himself. When he was “brought up” for this action, he persisted in remaining on the bench to try his own case.

At weddings the garter of the bride was often scrambled for, the idea being that it would bring luck and a speedy marriage to the one who caught it. The old custom of giving “bride-gloves” has come down to us in the giving of gloves and ties to the ushers. A New England wedding in the old days ended by kissing the bride, firing guns, and drinking New England rum. There was no wedding trip then, the newly married couple starting housekeeping immediately. It is interesting to note how often ministers and their families married into the households of other ministers, this being particularly true of the Mather family.

The meeting-houses were usually hot in summer and freezing cold in winter. The service began early in the morning and often lasted the greater part of the day; and it was necessary, therefore, that the worshippers provide themselves with foot-stoves. The First Church of Roxbury was destroyed by fire in 1747 owing to the fact that one of these stoves was left behind. The Old South Church not long afterwards passed a vote to prevent a similar occurrence. This vote reads, “Whereas danger is apprehended from the stoves that are frequently left in the meeting-house after the publique worship is over; Voted, that the saxton make diligent search on the Lord’s Day evening after a lecture, to see if any stoves are left in the house, and that if he find any there he take them to his own house; and it is expected that the owners of such stoves make reasonable satisfaction to the saxton for his trouble before they take them away.” Women often took hot potatoes in their muffs, and men sometimes brought their dogs to church to serve as foot-warmers, for which a charge of six-pence per dog was levied. The First Church was the first one in Boston to use a stove, although the meeting-house in Hadley holds the record of being the first in Massachusetts to adopt this innovation. When the Old South, in 1783, installed this luxury, the Evening Post bewailed the new custom as follows:—

“Extinct the sacred fire

of love,

Our zeal grown cold and dead,

In the house of God we fix a stove

To warm us in their stead.”

New England congregations became divided into stove and anti-stove factions. An amusing story is told about the wife of an anti-stove parson who was so unaccustomed to the heat that when the deacon referred in his sermon to “heaping coals of fire” she fainted. Upon reviving she declared that her condition was due entirely to the heat in the stove. It was pointed out, to her further discomfiture, that there had been no fire on this occasion.

Funerals were regarded as festivals and were considered of far greater importance than weddings. Many people attended, even little children, who often also acted as pall-bearers at the funerals of their young friends. The body was often borne in a chaise but usually on a farm wagon or by a group of bearers. The chief expense of a funeral was gloves, a pair of which was sent as an invitation to attend the ceremony. In some cases as many as one thousand pairs were given away, and often a man would name in his will the quality and cost of the gloves he requested be provided for his funeral. Often pall-bearers were given better gloves than the others who attended the services. One man sold his collection of three thousand funeral gloves for $640. Rings were also given to relatives and certain prominent people, and large were the collections of these rings that were made by some of the most popular and distinguished people of the community. These rings were usually made of gold with black enamel and often bore a coffin, skeleton, skull or urn on them; some were inscribed with mottoes such as “Death parts United Hearts” or “Prepared be to follow me,” or other equally cheerful suggestions. The Essex Institute in Salem has an interesting collection of these mourning rings. The Puritans usually drank wine at funerals, taking quite literally the remark “Give strong drink unto him that is ready to perish and wine unto those that be of heavy hearts.” It was often said that the temperance idea had “done for funerals,” at least as festivals. Regular invitations to funerals were sent out: invitations to other events usually went on the back of playing cards. At a meeting held in Faneuil Hall in 1767 the following resolution was passed: “And we further agree strictly to adhere to the late regulations respecting funerals and will not use any gloves but what are manufactured here, nor procure any new garments upon such occasions but what shall be absolutely necessary.”

The use of wine and rum was also referred to. Salem passed a regulation that the tolling of the bell should cost no more than eight-pence and that “the sextons are desired to toll the bells but four strokes in a minute.” There was also a rule that undertakers could charge no more than eight shillings for borrowed chairs. Sir Walter Scott said that his father enjoyed a funeral. The New Englanders, who met so seldom and who led such quiet lives, undoubtedly likewise enjoyed this ceremony and looked forward to getting a ring.

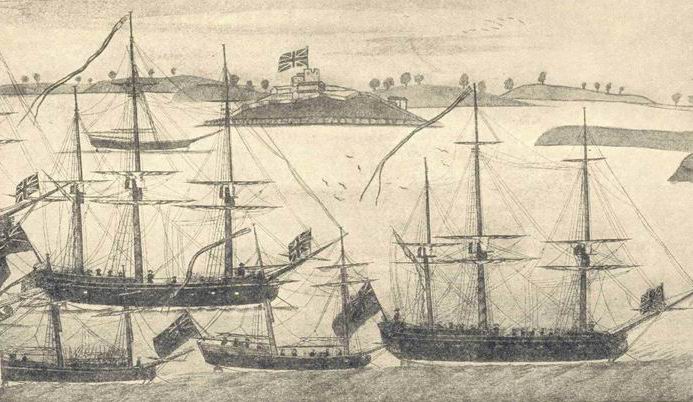

From a

print.

Collection of Bostonian Society.

THE

CASTLE.

The most ancient military post in the United States continuously occupied

for defence.

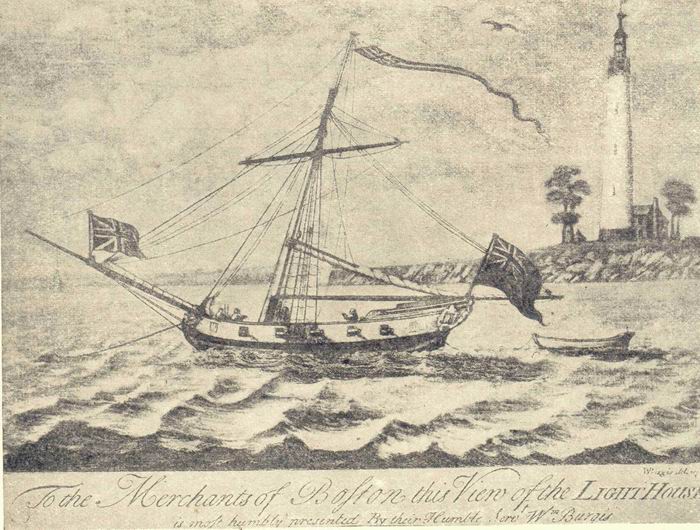

From a print.

Collection of Bostonian Society.

A SHIP OF THE MASSACHUSETTS BAY COLONY.