|

VOLTERRA

Volterra is the most

northerly of the great Etruscan cities of the west. It lies back some thirty

miles from the sea, on a towering great bluff of rock that gets all the winds

and sees all the world, looking out down the valley of the Cecina to the sea,

south over vale and high land to the tips of Elba, north to the imminent

mountains of Carrara, inward over the wide hills of the Pre-Apennines, to the

heart of Tuscany.

You leave the Rome — Pisa

train at Cecina, and slowly wind up the valley of the stream of that name, a

green, romantic, forgotten sort of valley, in spite of all the come-and-go of

ancient Etruscans and Romans, medieval Volterrans and Pisans, and modern

traffic. But the traffic is not heavy. Volterra is a sort of inland island,

still curiously isolated, and grim.

The small, forlorn

little train comes to a stop at the Saline de Volterra, the famous old salt

works now belonging to the State, where brine is pumped out of deep wells. What

passengers remain in the train are transferred to one old little coach across

the platform, and at length this coach starts to creep like a beetle up the

slope, up a cog-and-ratchet line, shoved by a small engine behind. Up the steep

but round slope among the vineyards and olives you pass almost at walking-pace,

and there is not a flower to be seen, only the beans make a whiff of perfume

now and then, on the chill air, as you rise and rise, above the valley below,

corning level with the high hills to south, and the bluff of rock with its two

or' three towers, ahead.

After a certain amount

of backing and changing, the fragment of a train eases up at a bit of a cold

wayside station, and is finished. The world lies below. You get out, transfer

yourself to a small ancient motor-omnibus and are rattled up to the final level

of the city, into a cold and gloomy little square, where the hotel is.

The hotel is simple and

somewhat rough, but quite friendly, pleasant in its haphazard way. And what is

more, it has central heating, and the heat is on, this cold, almost icy, April

afternoon. Volterra lies only 1800 feet above the sea, but it is right in the

wind, and cold as any Alp.

The day was Sunday, and

there was a sense of excitement and fussing, and a bustling in and out of

temporarily important persons, and altogether a smell of politics in the air.

The waiter brought us tea, of a sort, and I asked him what was doing. He

replied that a great banquet was to be given this evening to the new podestà

who had come from Florence to govern the city, under the new regime. And

evidently he felt that this was such a hugely important party occasion we poor

outsiders were of no account.

It was a cold, grey

afternoon, with winds round the hard dark corners of the hard, narrow medieval

town, and crowds of black-dressed, rather squat little men and pseudo-elegant

young women pushing and loitering in the streets, and altogether that sense of

furtive grinning and jeering and threatening which always accompanies a public

occasion — a political one especially — in Italy, in the more out-of-the-way

centres. It is as if the people, alabaster-workers and a few peasants, were not

sure which side they wanted to be on, and therefore were all the more ready to

exterminate anyone who was on the other side. This fundamental uneasiness,

indecision, is most curious in the Italian soul. It is as if the people could

never be wholeheartedly anything: because they can't trust anything. And this

inability to trust is at the root of the political extravagance and frenzy.

They don't trust themselves, so how can they trust their 'leaders' or their

party'?

Volterra, standing

sombre and chilly alone on her rock, has always, from Etruscan days on, been

grimly jealous of her own independence. Especially she has struggled against

the Florentine yoke. So what her actual feelings are, about this new-old sort

of village tyrant, the podestà, whom she is banqueting this evening, it

would be hard, probably, even for the Volterrans themselves to say. Anyhow the

cheeky girls salute one with the 'Roman' salute, out of sheer effrontery: a

salute which has nothing to do with me, so I don't return it. Politics of all

sorts are anathema. But in an Etruscan city which held out so long against Rome

I consider the Roman salute unbecoming, and the Roman imperium unmentionable.

It is amusing to see on

the walls, too, chalked fiercely up: Morte a Lenin! though that poor

gentleman has been long enough dead, surely even for a Volterran to have heard

of it. And more amusing still is the legend permanently painted: Mussolini

ha sempre ragione! Some are born infallible, some achieve infallibility,

and some have it thrust upon them.

But it is not for me to

put even my little finger in any political pie. I am sure every post-war

country has hard enough work to get itself governed, without outsiders

interfering or commenting. Let those rule who can rule.

We wander on, a little

dismally, looking at the stony stoniness of the medieval town. Perhaps on a

warm sunny day it might be pleasant, when shadow was attractive and a breeze

welcome. But on a cold, grey, windy afternoon of April, Sunday, always especially

dismal, with all the people in the streets, bored and uneasy, and the stone

buildings peculiarly sombre and hard and resistant, it is no fun. I don't care

about the bleak but truly medieval piazza: I don't care if the Palazzo Pubblico

has all sorts of amusing coats of arms on it: I don't care about the cold

cathedral, though it is rather nice really, with a glow of dusky candles and a

smell of Sunday incense: I am disappointed in the wooden sculpture of the

taking down of Jesus, and the bas-reliefs don't interest me. In short, I am

hard to please.

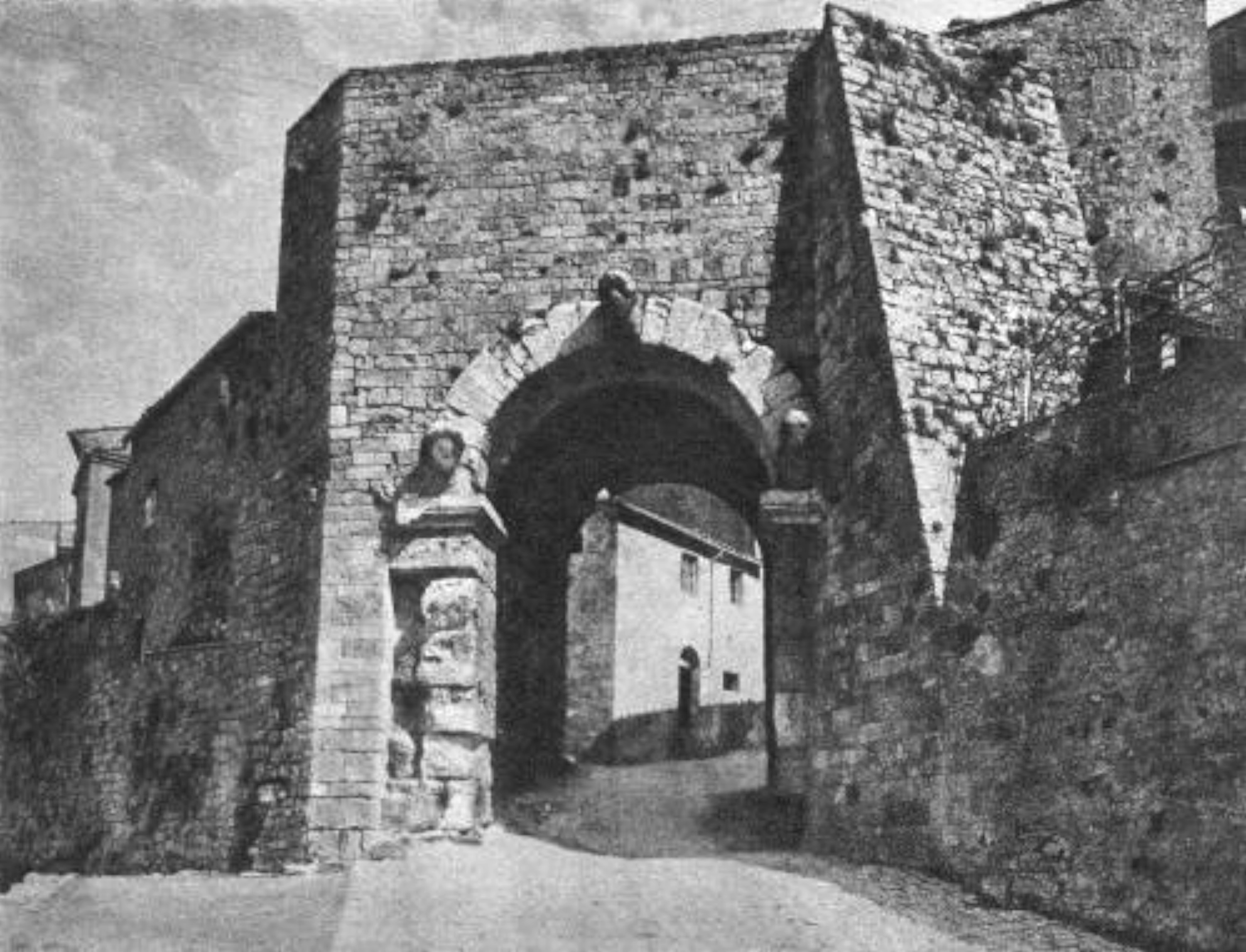

The modern town is not

very large. We went down a long, stony street, and out of the Porta dell'Arco,

the famous old Etruscan gate. It is a deep old gateway, almost a tunnel, with

the outer arch facing the desolate country on the skew, built at an angle to

the old road, to catch the approaching enemy on his right side, where the

shield did not cover him. Up handsome and round goes the arch, at a good

height, and with that peculiar weighty richness of ancient things; and three

dark heads, now worn featureless, reach out curiously and inquiringly, one from

the keystone of the arch, one from each of the arch bases, to gaze from the

city and into the steep hollow of the world beyond.

Strange, dark old Etruscan

heads of the city gate, even now they are featureless they still have a

peculiar, out-reaching life of their own. Ducati says they represented the

heads of slain enemies hung at the city gate. But they don't hang. They stretch

with curious eagerness forward. Nonsense about dead heads. They were city

deities of some sort.

And the archaeologists

say that only the doorposts of the outer arch, and the inner walls, are

Etruscan work. The Romans restored the arch, and set the heads back in their

old positions. (Unlike the Romans to set anything back in its old position!)

While the wall above the arch is merely medieval.

But we'll call it

Etruscan still. The roots of the gate, and the dark heads, these they cannot

take away from the Etruscans. And the heads are still on the watch.

The land falls away

steeply, across the road in front of the arch. The road itself turns east,

under the walls of the modern city, above the world: and the sides of the road,

as usual outside the gates, are dump-heaps, dump-heaps of plaster and rubble,

dump-heaps of the white powder from the alabaster works, the waste edge of the

town.

The path turns away

from under the city wall, and dips down along the brow of the hill. To the

right we can see the tower of the church of Santa Chiara, standing on a little

platform of the irregularly-dropping hill. And we are going there. So we dip

downwards above a Dantesque, desolate world, down to Santa Chiara, and beyond.

Here the path follows the top of what remains of the old Etruscan wall. On the

right are little olive-gardens and bits of wheat. Away beyond is the dismal

sort of crest of modern Volterra. We walk along, past the few flowers and the

thick ivy, and the bushes of broom and marjoram, on what was once the Etruscan

wall, far out from the present city wall. On the left the land drops steeply,

in uneven and unhappy descents.

The great hilltop or

headland on which Etruscan 'Volterra', Velathri, Vlathri, once stood

spreads out jaggedly, with deep-cleft valleys in between, more or less in view,

spreading two or three miles away. It is something like a hand, the bluff steep

of the palm sweeping in a great curve on the east and south, to seawards, the

peninsulas of fingers running jaggedly inland. And the great wall of the

Etruscan city swept round the south and eastern bluff, on the crest of steeps

and cliffs, turned north and crossed the first finger, or peninsula, then

started up hill and down dale over the fingers and into the declivities, a wild

and fierce sort of way, hemming in the great crest. The modern town occupies

merely the highest bit of the Etruscan city site.

The walls themselves

are not much to look at, when you climb down. They are only fragments, now,

huge fragments of embankment, rather than wall, built of uncemented square masonry,

in the grim, sad sort of stone. One only feels, for some reason, depressed. And

it is pleasant to look at the lover and his lass going along the top of the

ramparts, which are now olive-orchards, away from the town. At least they are

alive and cheerful and quick.

On from Santa Chiara

the road takes us through the grim and depressing little suburb-hamlet of San

Giusto, a black street that emerges upon the waste open place where the church

of San Giusto rises like a huge and astonishing barn. It is so tall, the

interior should be impressive. But no! It is merely nothing. The architects

have achieved nothing, with all that tallness. The children play around with

loud yells and ferocity. It is Sunday evening, near sundown, and cold.

Beyond this monument of

Christian dreariness we come to the Etruscan walls again, and what was

evidently once an Etruscan gate: a dip in the wall-bank, with the groove of an

old road running to it.

Here we sit on the

ancient heaps of masonry and look into weird yawning gulfs, like vast quarries.

The swallows, turning their blue backs, skim away from the ancient lips and

over the really dizzy depths, in the yellow light of evening, catching the

upward gusts of wind, and flickering aside like lost fragments of life, truly

frightening above those ghastly hollows. The lower depths are dark grey, ashy

in colour, and in part wet, and the whole things looks new, as if it were some

enormous quarry all slipping down.

This place is called Le

Balze — the cliffs. Apparently the waters which fall on the heights of

Volterra collect in part underneath the deep hill and wear away at some places

the lower strata, so that the earth falls in immense collapses. Across the

gulf, away from the town, stands a big, old, picturesque, isolated building, the

Badia or Monastery of the Camaldolesi, sad-looking, destined at last to be

devoured by Le Balze, its old walls already splitting and yielding.

From time to time,

going up to the town homewards, we come to the edge of the walls and look out

into the vast glow of gold, which is sunset, marvellous, the steep ravines

sinking in darkness, the farther valley silently, greenly gold, with hills

breathing luminously up, passing out into the pure, sheer gold gleams of the

far-off sea, in which a shadow, perhaps an island, moves like a mote of life.

And like great guardians the Carrara mountains jut forward, naked in the pure

light like flesh, with their crests portentous: so that they seem to be

advancing on us: while all the vast concavity of the west roars with gold

liquescency, as if the last hour had come, and the gods were smelting us all

back into yellow transmuted oneness.

But nothing is being

transmuted. We turn our faces, a little frightened, from the vast blaze of

gold, and in the dark, hard streets the town band is just chirping up, brassily

out of tune as usual, and the populace, with some maidens in white, are

streaming in crowds towards the piazza. And, like the band, the populace also

is out of tune, buzzing with the inevitable suppressed jeering. But they are

going to form a procession.

When we come to the

square in front of the hotel, and look out from the edge into the hollow world

of the west, the light is sunk red, redness gleams up from the far-off sea

below, pure and fierce, and the hollow places in between are dark. Over all the

world is a low red glint. But only the town, with its narrow streets and

electric light, is impervious.

The banquet,

apparently, was not till nine o'clock, and all was hubbub. B. and I dined alone

soon after seven, like two orphans whom the waiters managed to remember in

between whiles. They were so thrilled getting all the glasses and goblets and

decanters, hundreds of them, it seemed, out of the big chiffonnier-cupboard

that occupied the back of the dining-room, and whirling them away, stacks of

glittering glass, to the banquet-room: while out-of-work young men would poke

their heads in through the doorway, black hats on, overcoats hung over one

shoulder, and gaze with bright inquiry through the room, as though they expected

to see Lazarus risen, and not seeing him, would depart again to the nowhere

whence they came. A banquet is a banquet, even if it is given to the devil

himself; and the podestà may be an angel of light.

Outside was cold and

dark. In the distance the town band tooted spasmodically, as if it were

short-winded this chilly Sunday evening. And we, not bidden to the feast, went

to bed. To be awakened occasionally by sudden and roaring noises — perhaps

applause — and the loud and unmistakable howling of a child, well after

midnight.

Morning was cold and

grey again, with a chilly and forbidding country yawning and gaping and lapsing

away beneath us. The sea was invisible. We walked the narrow cold streets,

whose high, cold, dark stone walls seemed almost to press together, and we

looked in at the alabaster workshops, where workmen, in Monday-morning gloom

and half awakedness, were turning the soft alabaster, or cutting it out, or

polishing it.

Everybody knows

Volterra marble — so called — nowadays, because of the translucent bowls of it

which hang under the electric lights, as shades, in half the hotels of the

world. It is nearly as transparent as alum, and nearly as soft. They peel it

down as if it were soap, and tint it pink or amber or blue, and turn it into all

those things one does not want: tinted alabaster lampshades, light-bowls,

statues, tinted or untinted, vases, bowls with doves on the rim, or

vine-leaves, and similar curios. The trade seems to be going strong. Perhaps it

is the electric-light demand: perhaps there is a revival of interest in

'statuary'. Anyhow there is no love lost between a Volterran alabaster worker

and the lump of pale Volterran earth he turns into marketable form. Alas for

the goddess of sculptured form, she has gone from here also.

But it is the old

alabaster jars we want to see, not the new. As we hurry down the stony street

the rain, icy cold, begins to fall. We flee through the glass doors of the

museum, which has just opened, and which seems as if the alabaster inside had

to be kept at a low temperature, for the place is dead-cold as a refrigerator.

Cold, silent, empty,

unhappy the museum seems. But at last an old and dazed man arrives, in uniform,

and asks quite scared what we want. 'Why, to see the museum!' 'Ah! Ah! Ah si — si!'

It just dawns upon him that the museum is there to be looked at. 'Ah si, si,

Signori!'

We pay our tickets, and

start in. It is really a very attractive and pleasant museum, but we had struck

such a bitter cold April morning, with icy rain falling in the courtyard, that

I felt as near to being in the tomb as I have ever done. Yet very soon, in the

rooms with all those hundreds of little sarcophagi, ash-coffins, or urns, as

they are called, the strength of the old life began to warm one up.

Urn is not a good word,

because it suggests, to me at least, a vase, an amphora, a round and shapely

jar: perhaps through association with Keats' Ode to a Grecian Urn — which

vessel no doubt wasn't an urn at all, but a wine-jar — and with the 'tea-urn'

of children's parties. These Volterran urns, though correctly enough used for

storing the ashes of the dead, are not round, they are not jars, they are small

alabaster sarcophagi. And they are a peculiarity of Volterra. Probably because

the Volterrans had the alabaster to hand.

Anyhow here you have

them in hundreds, and they are curiously alive and attractive. They are not

considered very highly as 'art'. One of the latest Italian writers on Etruscan

things, Ducati, says: 'If they have small interest from the artistic point of

view, they are extremely valuable for the scenes they represent, either

mythological or relative to the beliefs in the after-life.'

George Dennis, however,

though he too does not find much 'art' in Etruscan things, says of the

Volterran ash-chests: 'The touches of Nature on these Etruscan urns, so simply

but eloquently expressed, must appeal to the sympathies of all — they are

chords to which every heart must respond; and I envy not the man who can walk

through this museum unmoved, without feeling a tear rise in his eye'

And recognizing ever

and anon

The breeze of Nature

stirring in his soul.

The breeze of Nature no

longer shakes dewdrops from our eves, at least so readily, but Dennis is more

alive than Ducati to that which is alive. What men mean nowadays by 'art' it

would be hard to say. Even Dennis said that the Etruscans never approached the

pure, the sublime, the perfect beauty which Flaxman reached. Today, this makes

us laugh: the Greekified illustrator of Pope's Homer! But the same

instinct lies at the back of our idea of 'art' still. Art is still to us

something which has been well cooked — like a plate of spaghetti. An ear of

wheat is not yet 'art'. Wait, wait till it has been turned into pure, into

perfect macaroni.

For me, I get more real

pleasure out of these Volterran ash-chests than out of — I had almost said, the

Parthenon frieze. One wearies of the aesthetic quality — a quality which takes

the edge off everything, and makes it seem 'boiled down'. A great deal of pure

Greek beauty has this boiled-down effect. It is too much cooked in the artistic

consciousness.

In Dennis's day a broken

Greek or Greekish amphora would fetch thousands of crowns in the market, if it

was the right 'period', etc. These Volterran urns fetched hardly anything.

Which is a mercy, or they would be scattered to the ends of the earth.

As it is, they are

fascinating, like an open book of life, and one has no sense of weariness with

them, though there are so many. They warm one up, like being in the midst of

life.

The downstairs rooms of

ash-chests contain those urns representing 'Etruscan' subjects: those of sea-monsters,

the seaman with fish-tail, and with wings, the sea-woman the same: or the man

with serpent-legs, and wings, or the woman the same. It was Etruscan to give

these creatures wings, not Greek.

If we remember that in

the old world the centre of all power was at the depths of the earth, and at

the depths of the sea, while the sun was only a moving subsidiary body: and

that the serpent represented the vivid powers of the inner earth, not only such

powers as volcanic and earthquake, but the quick powers that run up the roots

of plants and establish the great body of the tree, the tree of life, and run

up the feet and legs of man, to establish the heart: while the fish was the

symbol of the depths of the waters, whence even light is born: we shall see the

ancient power these symbols had over the imagination of the Volterrans. They

were a people faced with the sea, and living in a volcanic country.

Then the powers of the

earth and the powers of the sea take life as they give life. They have their

terrific as well as their prolific aspect.

Someone says the wings

of the water-deities represent evaporation towards the sun, and the curving

tails of the dolphin represent torrents. This is part of the great and

controlling ancient idea of the come-and-go of the life-powers, the surging up,

in a flutter of leaves and a radiation of wings, and the surging back, in

torrents and waves and the eternal downpour of death.

Other common symbolic

animals' in Volterra are the beaked griffins, the creatures of the powers that

tear asunder and, at the same time, are guardians of the treasure. They are

lion and eagle combined, of the sky and of the earth with caverns. They do not

allow the treasure of life, the gold, which we should perhaps translate as

consciousness, to be stolen by thieves of life. They are guardians of the

treasure: and then, they are the tearers asunder of those who must depart from

life.

It is these creatures,

creatures of the elements, which carry men away into death, over the border

between the elements. So is the dolphin, sometimes; and so the hippicampus, the

sea-horse; and so the centaur.

The horse is always the

symbol of the strong animal life of man: and sometimes he rises, a sea-horse,

from the ocean: and sometimes he is a land creature, and half-man. And so he

occurs on the tombs, as the passion in man returning into the sea, the soul

retreating into the death-world at the depths of the waters: or sometimes he is

a centaur, sometimes a female centaur, sometimes clothed in a lion-skin, to

show his dread aspect, bearing the soul back, away, off into the other-world.

It would be very

interesting to know if there were a definite connexion between the scene on the

ash-chest and the dead whose ashes it contained. When the fishtailed sea-god

entangles a man to bear him off, does it mean drowning at sea? And when a man

is caught in the writhing serpent-legs of the Medusa, or of the winged

snake-power, does it mean a fall to earth; a death from the earth, in some

manner; as a fall, or the dropping of a rock, or the bite of a snake? And the

soul carried off by a winged centaur: is it a man dead of some passion that

carried him away?

But more interesting

even than the symbolic scenes are those scenes from actual life, such as

boar-hunts, circus-games, processions, departures in covered wagons, ships

sailing away, city gates being stormed, sacrifice being performed, girls with

open scrolls, as if reading at school; many banquets with man and woman on the

banqueting couch, and slaves playing music, and children around: then so many

really tender farewell scenes, the dead saying good-bye to his wife, as he goes

on the journey, or as the chariot bears him off, or the horse waits; then the

soul alone, with the death-dealing spirits standing by with their hammers that

gave the blow. It is as Dennis says, the breeze of Nature stirs one's soul. I

asked the gentle old man if he knew anything about the urns. But no! no! He

knew nothing at all. He had only just come. He counted for nothing. So he

protested. He was one of those gentle, shy Italians too diffident even to look

at the chests he was guarding. But when I told him what I thought some of the

scenes meant he was fascinated like a child, full of wonder, almost breathless.

And I thought again, how much more Etruscan than Roman the Italian of today is:

sensitive, diffident, craving really for symbols and mysteries, able to be

delighted with true delight over small things, violent in spasms, and

altogether without sternness or natural will-to-power. The will-to-power is a

secondary thing in an Italian, reflected on to him from the Germanic races that

have almost engulfed him.

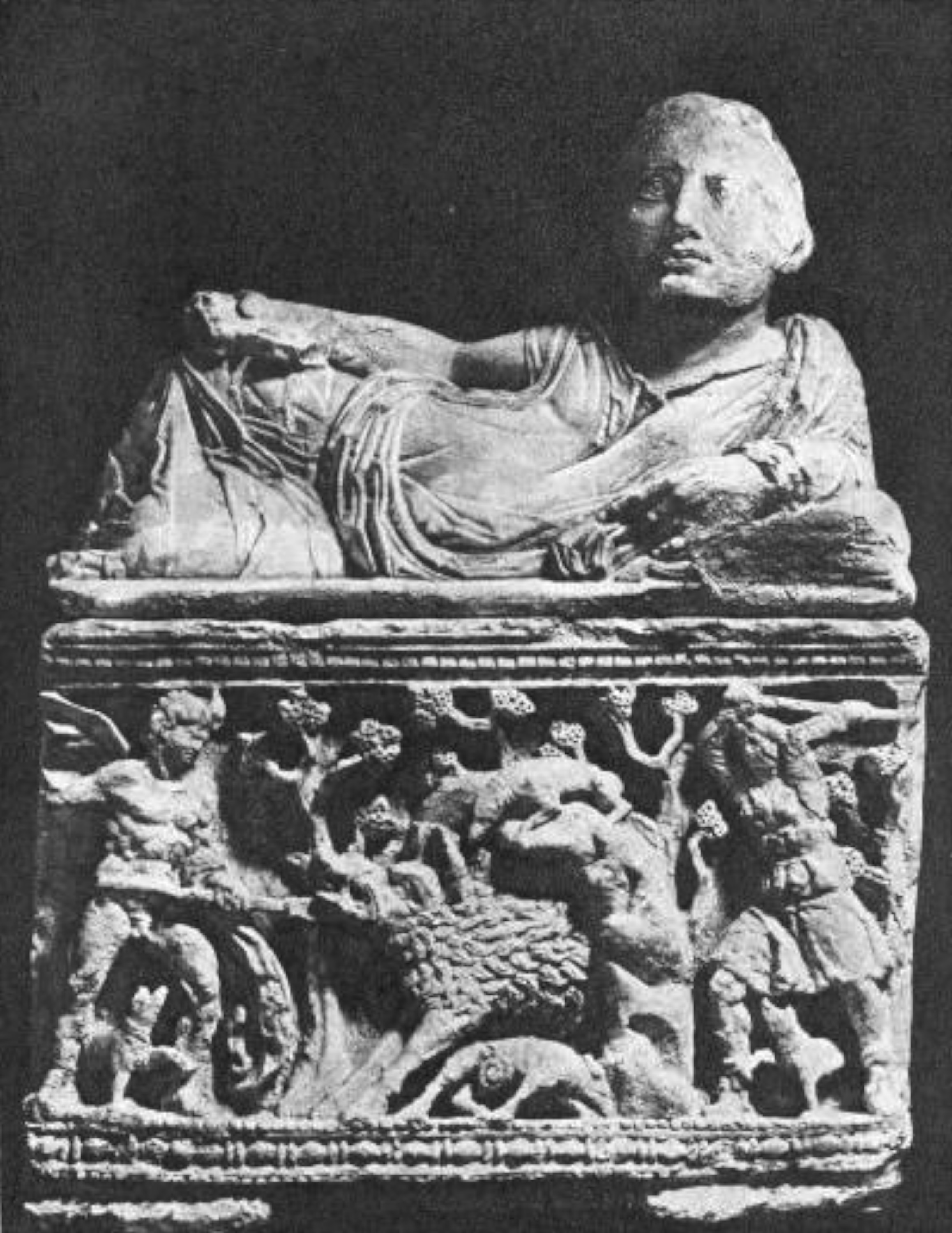

The boar-hunt is still

a favourite Italian sport, the grandest sport of Italy. And the Etruscans must

have loved it, for they represent it again and again, on the tombs. It is

difficult to know what exactly the boar symbolized to them. He occupies often

the centre of the scene, where the one who dies should be: and where the bull

of sacrifice is. And often he is attacked, not by men, but by young winged

boys, or by spirits. The dogs climb in the trees around him, the double axe is

swinging to come down on him, he lifts up his tusks in a fierce wild pathos.

The archaeologists say that it is Meleager and the boar of Calydon, or Hercules

and the fierce brute of Erymanthus. But this is not enough. It is a symbolic

scene: and it seems as if the boar were himself the victim this time, the wild,

fierce fatherly life hunted down by dogs and adversaries. For it is obviously

the boar who must die: he is not, like the lions and griffins, the attacker. He

is the father of life running free in the forest, and he must die. They say too

he represents winter: when the feasts for the dead were held. But on the very

oldest archaic vases the lion and the boar are facing each other, again and

again, in symbolic opposition.

Fascinating are the

scenes of departures, journeyings in covered wagons drawn by two or more

horses, accompanied by driver on foot and friend on horseback, and dogs, and

met by other horsemen coming down the road. Under the arched tarpaulin tilt of

the wagon reclines a man, or a woman, or a whole family: and all moves forward

along the highway with wonderful slow surge. And the wagon, as far as I saw, is

always drawn by horses, not by oxen.

This is surely the

journey of the soul. It is said to represent even the funeral procession, the

ash-chest being borne away to the cemetery, to be laid in the tomb. But the memory

in the scene seems much deeper than that. It gives so strongly the feeling of a

people who have trekked in wagons, like the Boers, or the Mormons, from one

land to another.

They say these

covered-wagon journeys are peculiar to Volterra, found represented in no other

Etruscan places. Altogether the feeling of the Volterran scenes is peculiar.

There is a great sense of journeying: as of a people which remembers its

migrations, by sea as well as land. And there is a curious restlessness, unlike

the dancing surety of southern Etruria: a touch of the Gothic.

In the upstairs rooms

there are many more ash-chests, but mostly representing Greek subjects: so

called. Helen and the Dioscuri, Pelops, Minotaur, Jason, Medea fleeing from

Corinth, Oedipus, and the Sphinx, Ulysses and the Sirens, Eteocles and

Polynices, Centaurs and Lapithae, the Sacrifice of Iphigenia — all are there,

just recognizable. There are so many Greek subjects that one archaeologist

suggested that these urns must have been made by a Greek colony planted there

in Volterra after the Roman conquest.

One might almost as

well say that Timon of Athens was written by a Greek colonist planted in

England after the overthrow of the Catholic Church. These 'Greek' ash-chests

are about as Grecian as Timon of Athens is. The Greeks would have done

them so much better.

No, the 'Greek' scenes

are innumerable, but it is only just recognizable what they mean. Whoever

carved these chests knew very little of the fables they were handling: and

fables they were, to the Etruscan artificers of that day, as they would be to

the Italians of this. The story was just used as a peg upon which the native

Volterran hung his fancy, as the Elizabethans used Greek stories for their

poems. Perhaps also the alabaster cutters were working from old models, or the

memory of them. Anyhow, the scenes show nothing of Hellas.

Most curious these 'classic'

subjects: so unclassic! To me they hint at the Gothic which lay unborn in the

future, far more than at the Hellenistic past of the Volterran Etruscan. For,

of course, all these alabaster urns are considered late in period, after the

fourth century B.C. The Christian sarcophagi of the fifth century A.D. seem

much more nearly kin to these ash-chests of Volterra than do contemporary Roman

chests: as if Christianity really rose, in Italy, out of Etruscan soil, rather

than out of Greco-Roman. And the first glimmering of that early, glad sort of

Christian art, the free touch of Gothic within the classic, seems evident in

the Etruscan scenes. The Greek and Roman 'boiled' sort of form gives way to a

raggedness of edge and a certain wildness of light and shade which promises the

later Gothic, but which is still held down by the heavy mysticism from the

East.

Very early Volterran

urns were probably plain stone or terra-cotta. But no doubt Volterra was a city

long before the Etruscans penetrated into it, and probably it never changed

character profoundly. To the end, the Volterrans burned their dead: there are

practically no long sarcophagi of Lucumones. And here most of all one feels

that the people of Volterra, or Velathri, were not Oriental, not the same as those

who made most show at Tarquinii. This was surely another tribe, wilder, cruder,

and far less influenced by the old Aegean influences. In Caere and Tarquinii

the aborigines were deeply overlaid by incoming influences from the East. Here

not! Here the wild and untamable Ligurian was neighbour, and perhaps kin, and

the town of wind and stone kept, and still keeps, its northern quality.

So there the ash-chests

are, an open book for anyone to read who will, according to his own fancy. They

are not more than two feet long, or thereabouts, so the figure on the lid is

queer and stunted. The classic Greek or Asiatic could not have borne that. It

is a sign of barbarism in itself. Here the northern spirit was too strong for

the Hellenic or Oriental or ancient Mediterranean instinct. The Lucumo and his

lady had to submit to being stunted, in their death-effigy. The head is nearly

life-size. The body is squashed small.

But there it is, a

portrait-effigy. Very often, the lid and the chest don't seem to belong together

at all. It is suggested that the lid was made during the lifetime of the

subject, with an attempt at real portraiture: while the chest was bought

ready-made, and apart. It may be so. Perhaps in Etruscan days there were the

alabaster workshops as there are today, only with rows of ash-chests portraying

all the vivid scenes we still can see: and perhaps you chose the one you wished

your ashes to lie in. But more probably, the workshops were there, the carved

ash-chests were there, but you did not select your own chest, since you did not

know what death you would die. Probably you only had your portrait carved on

the lid, and left the rest to the survivors.

So maybe, and most

probably, the mourning relatives hurriedly ordered the lid with the portrait-bust,

after the death of the near one, and then chose the most appropriate ash-chest.

Be it as it may, the two parts are often oddly assorted: and so they were found

with the ashes inside them.

But we must believe

that the figure on the lid, grotesquely shortened, is an attempt at a portrait.

There is none of the distinction of the southern Etruscan figures. The heads

are given the 'imperious' tilt of the Lucumones, but here it becomes almost

grotesque. The dead nobleman may be wearing the necklace of office and holding

the sacred patera or libation-dish in his hand; but he will not, in the

southern way, be represented ritualistically as naked to below the navel; his

shirt will come to his neck: and he may just as well be holding the tippling

wine-cup in his hand as the sacred patera; he may even have a wine-jug in his

other hand, in full carousal. Altogether the peculiar 'sacredness', the

inveterate symbolism of the southern Etruscans, is here gone. The religious

power is broken.

It is very evident in

the ladies: and so many of the figures are ladies. They are decked up in all

their splendour, but the mystical formality is lacking. They hold in their

hands wine-cups or fans or mirrors, pomegranates or perfume-boxes, or the queer

little books which perhaps were the wax tablets for writing upon. They may even

have the old sexual and death symbol of the pine-cone. But the power of the

symbol has almost vanished. The Gothic actuality and idealism begins to

supplant the profound physical religion of the southern Etruscans, the

true ancient world.

In the museum there are

jars and bits of bronze, and the pateras with the hollow knob in the middle.

You may put your two middle fingers in the patera, and hold it ready to make

the last libation of life, the first libation of death, in the correct Etruscan

fashion. But you will not, as so many of the men on these ash-chests do, hold

the symbolic dish upside down, with the two fingers thrust into the mundus'.

The torch upside down means the flame has gone below, to the underworld. But

the patera upside down is somehow shocking. One feels the Volterrans, or men of

Velathri, were slack in the ancient mysteries.

At last the rain

stopped crashing down icily in the silent inner courtyard; at last there was a

ray of sun. And we had seen all we could look at for one day. So we went out,

to try to get warmed by a kinder heaven.

There are one or two

tombs still open, especially two outside the Porta a Selci. But I believe, not

having seen them, they are of small importance. Nearly all the tombs that have

been opened in Volterra, their contents removed, have been filled in again, so

as not to lose two yards of the precious cultivable land of the peasants. There

were many tumuli: but most of them are levelled. And under some were curious

round tombs built of unsquared stones, unlike anything in southern Etruria. But

then, Volterra is altogether unlike southern Etruria.

One tomb has been

removed bodily to the garden of the archaeological museum in Florence: at least

its contents have. There it is built up again as it was when discovered in

Volterra in 1861, and all the ash-chests are said to be replaced as they stood

originally. It is called the Inghirami Tomb, from the famous Volterran

archaeologist Inghirami.

A few steps lead down

into the one circular chamber of the tomb, which is supported in the centre by

a square pillar, apparently supposed to be left in the rock. On the low stone

bed that encircles the tomb stand the ash-chests, a double row of them, in a

great ring encircling the shadow.

The tomb belongs all to

one family, and there must be sixty ash-chests, of alabaster, carved with the

well-known scenes. So that if this tomb is really arranged as it was

originally, and the ash-chests progress from the oldest to the latest counter-clockwise,

as is said, one ought to be able to see certainly a century or two of

development in the Volterran urns.

But one is filled with

doubt and misgiving. Why, oh why, wasn't the tomb left intact as it was found,

where it was found? The garden of the Florence museum is vastly instructive, if

you want object-lessons about the Etruscans. But who wants object-lessons about

vanished races? What one wants is a contact. The Etruscans are not a theory or

a thesis. If they are anything, they are an experience.

And the experience is

always spoilt. Museums, museums, museums, object-lessons rigged out to

illustrate the unsound theories of archaeologists, crazy attempts to coordinate

and get into a fixed order that which has no fixed order and will not be coordinated!

It is sickening! Why must all experience be systematized? Why must even the

vanished Etruscans be reduced to a system? They never will be. You break all

the eggs, and produce an omelette which is neither Etruscan nor Roman not

Italic nor Hittite, nor anything else, but just a systematized mess. Why can't

incompatible things be left incompatible? If you make an omelette out of a

hen's egg, a plover's, and an ostrich's, you won't have a grand amalgam or

unification of hen and plover and ostrich into something we may call ‘oviparity'.

You'll have that formless object, an omelette.

So it is here. If you

try to make a grand amalgam of Cerveteri and Tarquinia, Vulci, Vetulonia,

Volterra, Chiusi, Veii, then you won't get the essential Etruscan as a

result, but a cooked-up mess which has no life-meaning at all. A museum is not

a first-hand contact: it is an illustrated lecture. And what one wants is the

actual vital touch. I don't want to be 'instructed'; nor do many other people.

They could take the

more homeless objects for the museums, and still leave those that have a

place in their own place: the Inghirami Tomb here at Volterra.

But it is useless. We

walk up the hill and out of the Florence gate, into the shelter under the walls

of the huge medieval castle which is now a State prison. There is a promenade

below the ponderous walls, and a scrap of sun, and shelter from the biting

wind. A few citizens are promenading even now. And beyond, the bare green

country rises up in waves and sharp points, but it is like looking at the

choppy sea from the brow of a tall ship; here in Volterra we ride above all.

And behind us, in the

bleak fortress, are the prisoners. There is a man, an old man now, who has

written an opera inside those walls. He had a passion for the piano: and for

thirty years his wife nagged him when he played. So one day he silently and

suddenly killed her. So, the nagging of thirty years silenced, he got thirty

years of prison, and still is not allowed to play the piano. It is

curious.

There were also two men

who escaped. Silently and secretly they carved marvellous likenesses of

themselves out of the huge loaves of hard bread the prisoners get. Hair and

all, they made their own effigies lifelike. Then they laid them in the bed, so

that when the warder's light flashed on them he should say to himself: 'There

they lie sleeping, the dogs!'

And so they worked, and

they got away. It cost the governor, who loved his household of malefactors,

his job. He was kicked out. It is curious. He should have been rewarded, for

having such clever children, sculptors in bread.

THE END

PLATES.

14. Volterra. Porta

dell' Arco

15. Volterra.

Ash-chest showing the Boar-hunt.

16. Volterra.

Ash-chest showing Acteon and the Dogs.

|