| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2022

(Return

to Web

Text-ures)

| Click

Here to return to Etruscan Places Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

THE PAINTED TOMBS OF

TARQUINIA We arranged for the

guide to take us to the painted tombs, which are the real fame of Tarquinia.

After lunch we set out, climbing to the top of the town, and passing through

the south-west gate, on the level hillcrest. Looking back, the wall of the

town, medieval, with a bit of more ancient black wall lower down, stands blank.

Just outside the gate are one or two forlorn new houses, then ahead, the long,

running tableland of the hill, with the white highway dipping and going on to

Viterbo, inland. 'All this hill in

front,' said the guide, 'is tombs! All tombs! The city of the dead.' So! Then this hill is

the necropolis hill! The Etruscans never buried their dead within the city

walls. And the modern cemetery and the first Etruscan tombs lie almost close up

to the present city gate. Therefore, if the ancient city of Tarquinia lay on

this hill, it can have occupied no more space, hardly, than the present little

town of a few thousand people. Which seems impossible.

Far more probably, the city itself lay on that opposite hill there, which lies

splendid and unsullied, running parallel to us. We walk across the wild

bit of hilltop, where the stones crop gut, and the first rock-rose flutters,

and the asphodels stick up. This is the necropolis. Once it had many a tumulus,

and streets of tombs. Now there is no sign of any tombs: no tumulus, nothing

but the rough bare hill-crest, with stones and short grass and flowers, the sea

gleaming away to the right, under the sun, and the soft land inland glowing

very green and pure. But we see a little bit

of wall, built perhaps to cover a water-trough. Our guide goes straight towards

it. He is a fat, good-natured young man, who doesn't look as if he would be

interested in tombs. We are mistaken, however. He knows a good deal, and has a

quick, sensitive interest, absolutely unobtrusive, and turns out to be as

pleasant a companion for such a visit as one could wish to have. The bit of wall we see

is a little hood of masonry with an iron gate, covering a little flight of

steps leading down into the ground. One comes upon it all at once, in the rough

nothingness of the hillside. The guide kneels down to light his acetylene lamp,

and his old terrier lies down resignedly in the sun, in the breeze which rushes

persistently from the southwest, over these long, exposed hilltops. The lamp begins to

shine and smell, then to shine without smelling: the guide opens the iron gate,

and we descend the steep steps down into the tomb. It seems a dark little hole

underground: a dark little hole, after the sun of the upper world! But the

guide's lamp begins to flare up, and we find ourselves in a little chamber in

the rock, just a small, bare little cell of a room that some anchorite might

have lived in. It is so small and bare and familiar, quite unlike the rather

splendid spacious tombs at Cerveteri. But the lamp flares

bright, we get used to the change of light, and see the paintings on the little

walls. It is the Tomb of Hunting and Fishing, so called from the pictures on

the walls, and it is supposed to date from the sixth century B.C. It is very

badly damaged, pieces of the wall have fallen away, damp has eaten into the

colours, nothing seems to be left. Yet in the dimness we perceive flights of

birds flying through the haze, with the draught of life still in their wings.

And as we take heart and look closer we see the little room is frescoed all

round with hazy sky and sea, with birds flying and fishes leaping, and little

men hunting, fishing, rowing in boats. The lower part of the wall is all a

blue-green of sea with a silhouette surface that ripples all round the room.

From the sea rises a tall rock, off which a naked man, shadowy but still

distinct, is beautifully and cleanly diving into the sea, while a companion

climbs up the rock after him, and on the water a boat waits with rested oars in

it, three men watching the diver, the middle man standing up naked, holding out

his arms. Meanwhile a great dolphin leaps behind the boat, a flight of birds

soars upwards to pass the rock, in the clear air. Above all, from the bands of

colour that border the wall at the top hang the regular loops of garlands,

garlands of flowers and leaves and buds and berries, garlands which belong to

maidens and to women, and which represent the flowery circle of the female life

and sex. The top border of the wall is formed of horizontal stripes or ribands

of colour that go all round the room, red and black and dull gold and blue and

primrose, and these are the colours that occur invariably. Men are nearly

always painted a darkish red, which is the colour of many Italians when they go

naked in the sun, as the Etruscans went. Women are coloured paler, because

women did not go naked in the sun. At the end of the room,

where there is a recess in the wall, is painted another rock rising from the

sea, and on it a man with a sling is taking aim at the birds which rise

scattering this way and that. A boat with a big paddle oar is holding off from

the rock, a naked man amidships is giving a queer salute to the slinger, a man

kneels over the bows with his back to the others, and is letting down .a net.

The prow of the boat has a beautifully painted eye, so the vessel shall see

where it is going. In Syracuse you will see many a two-eyed boat today come

swimming in to quay. One dolphin is diving down into the sea, one is leaping

out. The birds fly, and the garlands hang from the border. It is all small and gay

and quick with life, spontaneous as only young life can be. If only it were not

so much damaged, one would be happy, because here is the real Etruscan

liveliness and naturalness. It is not impressive or grand. But if you are

content with just a sense of the quick ripple of life, then here it is. The little tomb is

empty, save for its shadowy paintings. It had no bed of rock around it: only a

deep niche for holding vases, perhaps vases of precious things. The sarcophagus

on the floor, perhaps under the slinger on the end wall. And it stood alone,

for this is an individual tomb, for one person only, as is usual in the older

tombs of this necropolis. In the gable triangle

of the end wall, above the slinger and the boat, the space is filled in with

one of the frequent Etruscan banqueting scenes of the dead. The dead man, sadly

obliterated, reclines upon his banqueting couch with his fiat wine-dish in his

hand, resting on his elbow, and beside him, also half risen, reclines a

handsome and jewelled lady in fine robes, apparently resting her left hand upon

the naked breast of the man, and in her right holding up to him the garland — the

garland of the female festive offering. Behind the man stands a naked

slave-boy, perhaps with music, while another naked slave is just filling a

wine-jug from a handsome amphora or wine-jar at the side. On the woman's side

stands a maiden, apparently playing the flute: for a woman was supposed to play

the flute at classic funerals; and beyond sit two maidens with garlands, one

turning round to watch the banqueting pair, the other with her back to it all.

Beyond the maidens in the corner are more garlands, and two birds, perhaps

doves. On the wall behind the head of the banqueting lady is a problematic

object, perhaps a bird-cage. The scene is natural as

life, and yet it has a heavy archaic fullness of meaning. It is the

death-banquet; and at the same time it is the dead man banqueting in the

underworld; for the underworld of the Etruscans was a gay place. While the

living feasted out of doors, at the tomb of the dead, the dead himself feasted

in like manner, with a lady to offer him garlands and slaves to bring him wine,

away in the underworld. For the life on earth was so good, the life below could

but be a continuance of it. This profound belief in

life, acceptance of life, seems characteristic of the Etruscans. It is still

vivid in the painted tombs. There is a certain dance and glamour in all the

movements, even in those of the naked slave men. They are by no means

downtrodden menials, let later Romans say what they will. The slaves in the

tombs are surging with full life. We come up the steps

into the upper world, the sea-breeze and the sun. The old dog shambles to his

feet, the guide blows out his lamp and locks the gate, we set off again, the

dog trundling apathetic at his master's heels, the master speaking to him with

that soft Italian familiarity which seems so very different from the spirit of

Rome, the strong-willed Latin. The guide steers across

the hilltop, in the clear afternoon sun, towards another little hood of

masonry. And one notices there is quite a number of these little gateways,

built by the Government to cover the steps that lead down to the separate small

tombs. It is utterly unlike Cerveteri, though the two places are not forty

miles apart. Here there is no stately tumulus city, with its highroad between

the tombs, and inside, rather noble, many-roomed houses of the dead, Here the

little one-room tombs seem scattered at random on the hilltop, here and there:

though probably, if excavations were fully carried out, here also we should

find a regular city of the dead, with its streets and crossways. And probably

each tomb had its little tumulus of piled earth, so that even above-ground

there were streets of mounds with tomb entrances. But even so, it would be

different from Cerveteri, from Caere; the mounds would be so small, the streets

surely irregular. Anyhow, today there are scattered little one-room tombs, and

we dive down into them just like rabbits popping down a hole. The place is a

warren. It is interesting to

find it so different from Cerveteri. The Etruscans carried out perfectly what

seems to be the Italian instinct: to have single, independent cities, with a

certain surrounding territory, each district speaking its own dialect and

feeling at home in its own little capital, yet the whole confederacy of

city-states loosely linked together by a common religion and a more-or-less

common interest. Even today Lucca is very different from Ferrara, and the

language is hardly the same. In ancient Etruria this isolation of cities

developing according to their own idiosyncrasy, within the loose union of a

so-called nation, must have been complete, The contact between the plebs, the

mass of the people, of Caere and Tarquinii must have been almost null. They

were, no doubt, foreigners to one another. Only the Lucumones, the ruling

sacred magistrates of noble family, the priests and the other nobles, and the

merchants, must have kept up an intercommunion, speaking 'correct' Etruscan,

while the people, no doubt, spoke dialects varying so widely as to be different

languages. To get any idea of the pre-Roman past we must break up the

conception of oneness and uniformity, and see an endless confusion of

differences. We are diving down into

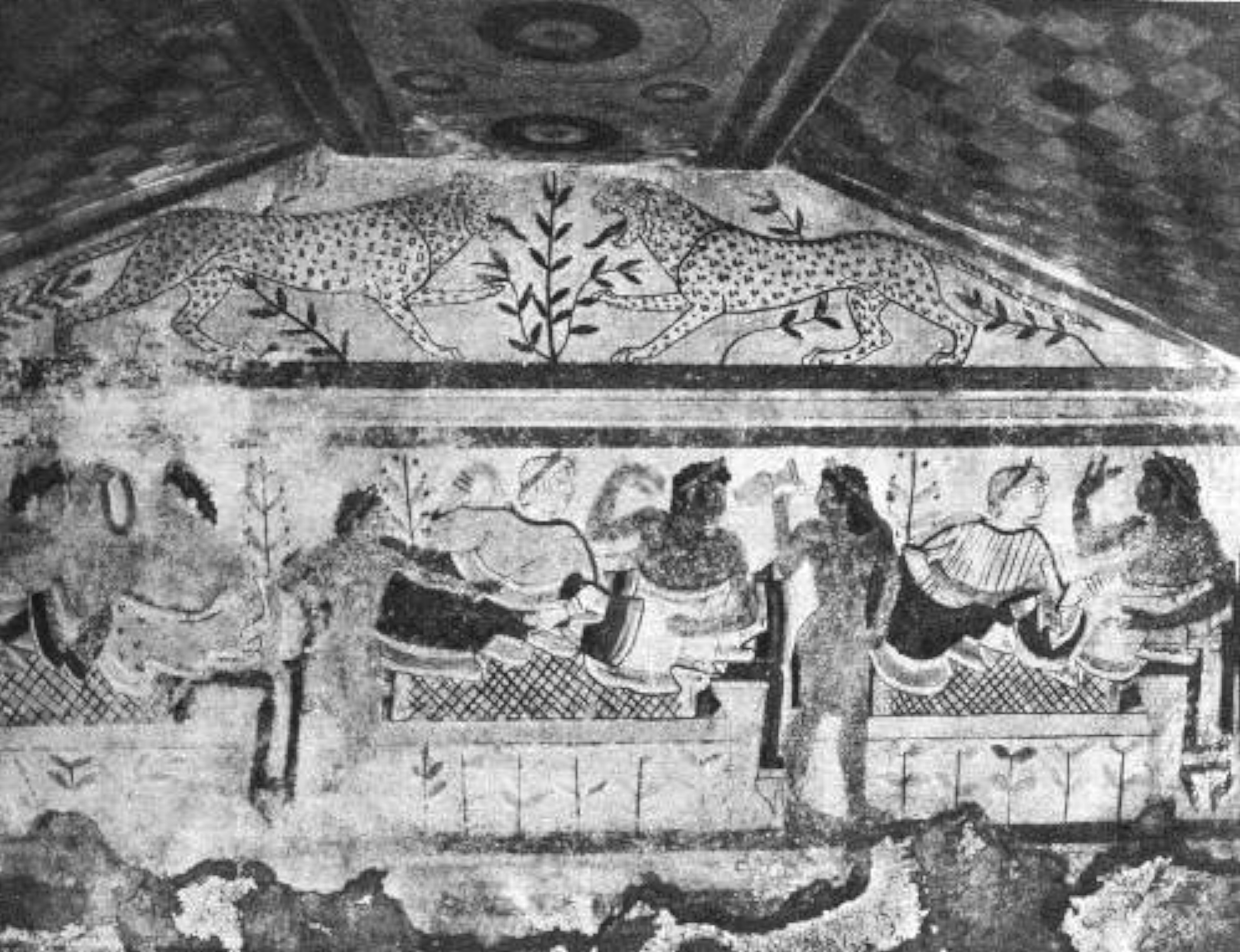

another tomb, called, says the guide, the Tomb of the Leopards. Every tomb has

been given a name, to distinguish it from its neighbours. The Tomb of the

Leopards has two spotted leopards in the triangle of the end wall, between the

roof-slopes. Hence its name. The Tomb of the

Leopards is a charming, cosy little room, and the paintings on the walls have

not been so very much damaged. All the tombs are ruined to some degree by

weather and vulgar vandalism, having been left and neglected like common holes,

when they had been broken open again and rifled to the last gasp. But still the paintings

are fresh and alive: the ochre-reds and blacks and blues and blue-greens are

curiously alive and harmonious on the creamy yellow walls. Most of the tomb

walls have had a thin coat of stucco, but it is of the same paste as the living

rock, which is fine and yellow, and weathers to a lovely creamy gold, a

beautiful colour for a background. The walls of this

little tomb are a dance of real delight. The room seems inhabited still by

Etruscans of the sixth century before Christ, a vivid, life-accepting people,

who must have lived with real fullness. On come the dancers and the

music-players, moving in a broad frieze towards the front wall of the tomb, the

wall facing us as we enter from the dark stairs, and where the banquet is going

on in all its glory. Above the banquet, in the gable angle, are the two spotted

leopards, heraldically facing each other across a little tree. And the ceiling

of rock has chequered slopes of red and black and yellow and blue squares, with

a roof-beam painted with coloured circles, dark red and blue and yellow. So

that all is colour, and we do not seem to be underground at all, but in some

gay chamber of the past. The dancers on the

right wall move with a strange, powerful alertness onwards. The men are dressed

only in a loose coloured scarf, or in the gay handsome chlamys draped as a

mantle. The subulo plays the double flute the Etruscans loved so much, touching

the stops with big, exaggerated hands, the man behind him touches the

seven-stringed lyre, the man in front turns round and signals with his left

hand, holding a big wine-bowl in his right. And so they move on, on their long,

sandalled feet, past the little berried olive-trees, swiftly going with their

limbs full of life, full of life to the tips. This sense of vigorous,

strong-bodied liveliness is characteristic of the Etruscans, and is somehow

beyond art. You cannot think of art, but only of life itself, as if this were

the very life of the Etruscans, dancing in their coloured wraps with massive

yet exuberant naked limbs, ruddy from the air and the sea-light, dancing and

fluting along through the little olive-trees, out in the fresh day. The end wall has a

splendid banqueting scene. The feasters recline upon a checked or tartan

couch-cover, on the banqueting couch, and in the open air, for they have little

trees behind them. The six feasters are bold and full of life like the dancers,

but they are strong, they keep their life so beautifully and richly inside

themselves, they are not loose, they don't lose themselves even in their wild

moments. They lie in pairs, man and woman, reclining equally on the couch,

curiously friendly. The two end women are called hetaerae, courtesans;

chiefly because they have yellow hair, which seems to have been a favourite

feature in a woman of pleasure. The men are dark and ruddy, and naked to the

waist. The women, sketched in on the creamy rock, are fair, and wear thin

gowns, with rich mantles round their hips. They have a certain free bold look,

and perhaps really are courtesans. The man at the end is

holding up, between thumb and forefinger, an egg, showing it to the

yellow-haired woman who reclines next to him, she who is putting out her left

hand as if to touch his breast. He, in his right hand, holds a large wine-dish,

for the revel. The next couple, man

and fair-haired woman, are looking round and making the salute with the right

hand curved over, in the usual Etruscan gesture. It seems as if they too are saluting

the mysterious egg held up by the man at the end; who is, no doubt, the man who

has died, and whose feast is being celebrated. But in front of the second

couple a naked slave with a chaplet on his head is brandishing an empty

wine-jug, as if to say he is fetching more wine. Another slave farther down is

holding out a curious thing like a little axe, or fan. The last two feasters

are rather damaged. One of them is holding up a garland to the other, but not

putting it over his head as they still put a garland over your head, in India,

to honour you. Above the banqueters,

in the gable angle, the two great spotted male leopards hang out their tongues

and face each other heraldically, lifting a paw, on either side of a little

tree. They are the leopards or panthers of the underworld Bacchus, guarding the

exits and the entrances of the passion of life. There is a mystery and

a portentousness in the simple scenes which go deeper than commonplace life. It

seems all so gay and light. Yet there is a certain weight, or depth of

significance that goes beyond aesthetic beauty. If one once starts

looking, there is much to see. But if one glances merely, there is nothing but

a pathetic little room with unimposing, half-obliterated, scratchy little

paintings in tempera. There are many tombs.

When we have seen one, up we go, a little bewildered, into the afternoon sun,

across a tract of rough, tormented hill, and down again to the underground,

like rabbits in a warren. The hilltop is really a warren of tombs. And gradually

the underworld of the Etruscans becomes more real than the above day of the

afternoon. One begins to live with the painted dancers and feasters and

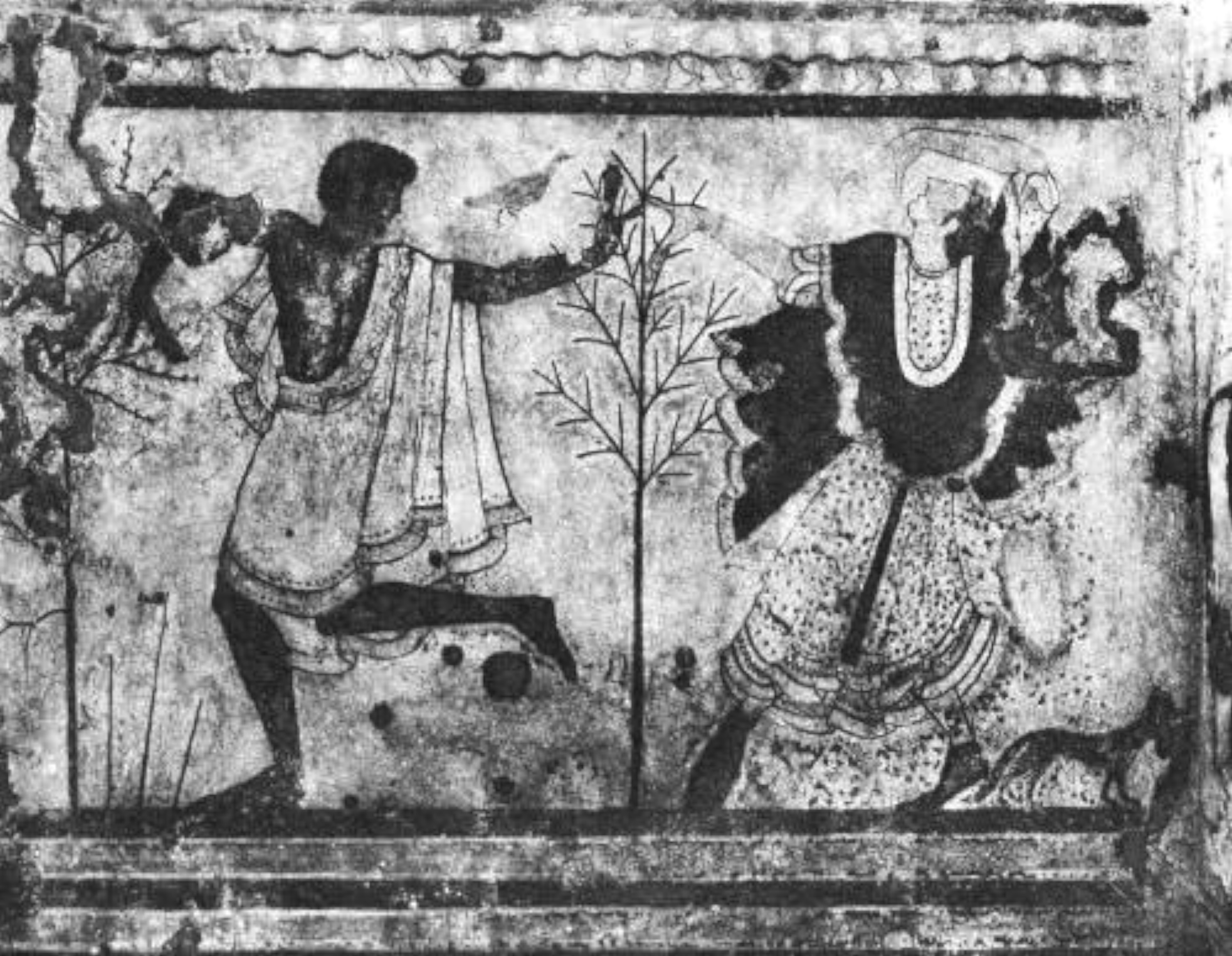

mourners, and to look eagerly for them. A very lovely dance

tomb is the Tomba del Triclinio, or del Convito, both of which

mean: Tomb of the Feast. In size and shape this is much the same as the other

tombs we have seen. It is a little chamber about fifteen feet by eleven, six

feet high at the walls, about eight feet at the centre. It is again a tomb for

one person, like nearly all the old painted tombs here. So there is no inner

furnishing. Only the farther half of the rock-floor, the pale yellow-white

rock, is raised two or three inches, and on one side of this raised part are

the four holes where the feet of the sarcophagus stood. For the rest, the tomb

has only its painted walls and ceiling. And how lovely these

have been, and still are I The band of dancing figures that go round the room

still is bright in colour, fresh, the women in thin spotted dresses of linen

muslin and coloured mantles with fine borders, the men merely in a scarf.

Wildly the bacchic woman throws back her head and curves out her long, strong

fingers, wild and yet contained within herself, while the broad-bodied young

man turns round to her, lifting his dancing hand to hers till the thumbs all

but touch. They are dancing in the open, past little trees, and birds are

running, and a little fox-tailed dog is watching something with the naïve

intensity of the young. Wildly and delightedly dances the next woman, every bit

of her, in her soft boots and her bordered mantle, with jewels on her arms;

till one remembers the old dictum, that every part of the body and of the anima

shall know religion, and be in touch with the gods. Towards her comes the young

man piping on the double flute, and dancing as he comes. He is clothed only in

a fine linen scarf with a border, that hangs over his arms, and his strong legs

dance of themselves, so full of life. Yet, too, there is a certain solemn

intensity in his face, as he turns to the woman beyond him, who stoops in a bow

to him as she vibrates her castanets. She is drawn

fair-skinned, as all the women are, and he is of a dark red colour. That is the

convention, in the tombs. But it is more than convention. In the early days men

smeared themselves with scarlet when they took on their sacred natures. The Red

Indians still do it. When they wish to figure in their sacred and portentous

selves they smear their bodies all over with red. That must be why they are called

Red Indians. In the past, for all serious or solemn occasions, they rubbed red

pigment into their skins. And the same today. And today, when they wish to put

strength into their vision, and to see true, they smear round their eyes with

vermilion, rubbing it into the skin. You may meet them so, in the streets of

the American towns. It is a very old

custom. The American Indian will tell you: 'The red paint, it is medicine, make

you see!' But he means medicine in a different sense from ours. It is deeper

even than magic. Vermilion is the colour of his sacred or potent or god body.

Apparently it was so in all the ancient world. Man all scarlet was his bodily

godly self. We know the kings of ancient Rome, who were probably Etruscans,

appeared in public with their faces painted vermilion with minium. And Ezekiel

says (23: 14, 15): 'She saw men pourtrayed upon the wall, the images of the

Chaldeans pourtrayed with vermilion...all of them princes to look to, after the

manner of the Babylonians of Chaldea, the land of their nativity.' It is then partly a

convention, and partly a symbol, with the Etruscans, to represent their men red

in colour, a strong red. Here in the tombs everything is in its sacred or

inner-significant aspect. But also the red colour is not so very unnatural.

When the Italian today goes almost naked on the beach he becomes of a lovely

dark ruddy colour, dark as any Indian. And the Etruscans went a good deal

naked. The sun painted them with the sacred minium. The dancers dance on,

the birds run, at the foot of a little tree a rabbit crouches in a bunch,

bunched with life. And on the tree hangs a narrow, fringed scarf, like a

priest's stole; another symbol. The end wall has a

banqueting scene, rather damaged, but still interesting. We see two separate

couches, and a man and a woman on each. The woman this time is dark-haired, so

she need not be a courtesan. The Etruscans shared the banqueting bench with

their wives; which is more than the Greeks or Romans did, at this period. The

classic world thought it indecent for an honest woman to recline as the men

did, even at the family table. If the woman appeared at all, she must sit up

straight, in a chair. Here, the women recline

calmly with the men, and one shows a bare foot at the end of the dark couch. In

front of the lecti, the couches, is in each case a little low square table

bearing delicate dishes of food for the feasters. But they are not eating. One

woman is lifting her hand to her head in a strange salute to the robed piper at

the end, the other woman seems with the lifted hand to be saying No! to the

charming maid, perhaps a servant, who stands at her side, presumably offering

the alabastron, or ointment-jar, while the man at the end apparently is

holding up an egg. Wreaths hang from the ivy-border above, a boy is bringing a

wine-jug, the music goes on, and under the beds a cat is on the prowl, while an

alert cock watches him. The silly partridge, however, turns his back, stepping

innocently along. This lovely tomb has a

pattern of ivy and ivy berries, the ivy of the underworld Bacchus, along the

roof-beam and in a border round the top of the walls. The roof-slopes are

chequered in red and black, white, blue, brown, and yellow squares. In the

gable angle, instead of the heraldic beasts, two naked men are sitting reaching

back to the centre of an ivy-covered altar, arm outstretched across the ivy.

But one man is almost obliterated. At the foot of the other man, in the tight

angle of the roof, is a pigeon, the bird of the soul that coos out of the

unseen. This tomb has been open

since 1830, and is still fresh. It is interesting to see, in Fritz Weege's

book, Etruskische Malerei, a reproduction of an old water-colour drawing

of the dancers on the right wall. It is a good drawing, yet, as one looks

closer, it is quite often out, both in line and position. These Etruscan

paintings, not being in our convention, are very difficult to copy. The picture

shows my rabbit all spotted, as if it were some queer cat. And it shows a

squirrel in the little tree in front of the piper, and flowers, and many

details that have now disappeared. But it is a good

drawing, unlike some that Weege reproduces, which are so Flaxmanized and

Greekified; and in jade according to what our great-grandfathers thought they ought

to be, as to be really funny, and a warning for ever against thinking how

things ought to be, when already they are quite perfectly what they are. We climb up to the

world, and pass for a few minutes through the open day. Then down we go again.

In the Tomb of the Bacchanti the colours have almost gone. But still we see, on

the end wall, a strange wondering dancer out of the mists of time carrying his

zither, and beyond him, beyond the little tree, a man of the dim ancient world,

a man with a short beard, strong and mysteriously male, is reaching for a wild

archaic maiden who throws up her hands and turns back to him her excited,

subtle face. It is wonderful, the strength and mystery of old life that comes

out of these faded figures. The Etruscans are still there, upon the wall. Above the figures, in

the gable angle, two spotted deer are prancing heraldically towards one

another, on either side the altar, and behind them two dark lions, with pale

manes and with tongues hanging out, are putting up a paw to seize them on the

haunch. So the old story repeats itself. From the striped border

rude garlands are hanging, and on the roof are little painted stars, or

four-petalled flowers. So much has vanished! Yet even in the last breath of

colour and form, how much life there is! In the Tomba del

Morto, the Tomb of the Dead Man, the banqueting scene is replaced by a

scene, apparently, of a dead man on his bed, with a woman leaning gently over

to cover his face. It is almost like a banquet scene. But it is so badly

damaged! In the gable above, two dark heraldic lions are lifting the paw

against two leaping, frightened, backward-looking birds. This is a new

variation. On the broken wall are the dancing legs of a man, and there is more

life in these Etruscan legs, fragment as they are, than in the whole bodies of

men today. Then there is one really impressive dark figure of a naked man who

throws up his arms so that his great wine-bowl stands vertical, and with spread

hand and closed face gives a strange gesture of finality. He has a chaplet on

his head, and a small pointed beard, and lives there shadowy and significant. Lovely again is the Tomba

delle Leonesse, the Tomb of the Lionesses. In its gable two spotted

lionesses swing their bell-like udders, heraldically facing one another across

the altar. Beneath is a great vase, and a flute-player playing to it on one

side, a zither-player on the other, making music to its sacred contents. Then

on either side of these goes a narrow frieze of dancers, very strong and lively

in their prancing. Under the frieze of dancers is a lotus dado, and below that

again, all round the room, the dolphins are leaping, leaping all downwards into

the rippling sea, while birds fly between the fishes. On the right wall

reclines a very impressive dark red man wearing a curious cap, or head-dress,

that has long tails like long plaits. In his right hand he holds up an egg, and

in his left is the shallow wine-bowl of the feast. The scarf or stole of his

human office hangs from a tree before him, and the garland of his human delight

hangs at his side. He holds up the egg of resurrection, within which the germ

sleeps as the soul sleeps in the tomb, before it breaks the shell and emerges

again. There is another reclining man, much obliterated, and beside him hangs a

garland or chain like the chains of dandelion-sterns we used to make as

children. And this man has a naked flute-boy, lovely in naked outline, coming towards

him. The Tomba della

Pulcella, or Tomb of the Maiden, has faded but vigorous figures at the

banquet, and very ornate couch-covers in squares and the key-pattern, and very

handsome mantles. The Tomba dei Vasi

Dipinti, Tomb of the Painted Vases, has great amphorae painted on the side

wall, and springing towards them is a weird dancer, the ends of his waist-cloth

flying. The amphorae, two of them, have scenes painted on them, which can still

be made out. On the end wall is a gentle little banquet scene, the bearded man

softly touching the woman with him under the chin, a slave-boy standing

childishly behind, and an alert dog under the couch. The kylix, or

wine-bowl, that the man holds is surely the biggest on record; exaggerated, no

doubt, to show the very special importance of the feast. Rather gentle and

lovely is the way he touches the woman under the chin, with a delicate caress.

That again is one of the charms of the Etruscan paintings: they really have the

sense of touch; the people and the creatures are all really in touch. It is one

of the rarest qualities, in life as well as in art. There is plenty of pawing

and laying hold, but no real touch. In pictures especially, the people may be

in contact, embracing or laying hands on one another. But there is no soft flow

of touch. The touch does not come from the middle of the human being. It is

merely a contact of surfaces, and a juxtaposition of objects. This is what

makes so many of the great masters boring, in spite of all their clever

composition. Here, in this faded Etruscan painting, there is a quiet flow of

touch that unites the man and the woman on the couch, the timid boy behind, the

dog that lifts his nose, even the very garlands that hang from the wall. Above the banquet, in

the triangle, instead of lions or leopards, we have the hippocampus, a

favourite animal of the Etruscan imagination. It is a horse that ends in a

long, flowing fish-tail. Here these two hippocampi face one another prancing

their front legs, while their fish-tails flow away into the narrow angle of the

roof. They are a favourite symbol of the seaboard Etruscans. In the Tomba del

Vecchio, the Tomb of the Old Man, a beautiful woman with her hair dressed

backwards into the long cone of the East, so that her head is like a sloping

acorn, offers her elegant, twisted garland to the white-bearded old man, who is

now beyond garlands. He lifts his left hand up at her, with the rich gesture of

these people, that must mean something each time. Above them, the

prancing spotted deer are being seized in the haunch by two lions. And the

waves of obliteration, wastage of time and damage of men, are silently passing

over all. So we go on, seeing

tomb after tomb, dimness after dimness, divided between the pleasure of finding

so much and the disappointment that so little remains. One tomb after another,

and nearly everything faded or eaten away, or corroded with alkali, or broken

wilfully. Fragments of people at banquets, limbs that dance without dancers,

birds that fly in nowhere, lions whose devouring heads are devoured away! Once

it was all bright and dancing: the delight of the underworld; honouring the

dead with wine, and flutes playing for a dance, and limbs whirling and

pressing. And it was deep and sincere honour rendered to the dead and to the

mysteries. It is contrary to our ideas; but the ancients had their own

philosophy for it. As the pagan old writer says: 'For no part of us nor of our

bodies shall be, which doth not feel religion: and let there be no lack of

singing for the soul, no lack of leaping and of dancing for the knees and

heart; for all these know the gods.' Which is very evident

in the Etruscan dancers. They know the gods in their very finger-tips. The

wonderful fragments of limbs and bodies that dance on in a field of obliteration

still know the gods, and made it evident to us. But we can hardly see

any more tombs. The upper air seems pallid and bodiless, as we emerge once

more, white with the light of the sea and the coming evening. And spent and

slow the old dog rises once more to follow after. We decide that the Tomba

delle Iserizioni, the Tomb of the Inscriptions, shall be our last for

today. It is dim but fascinating, as the lamp flares up, and we see in front of

us the end wall, painted with a false door studded with pale studs, as if it

led to another chamber beyond; and riding from the left, a trail of shadowy

tall horsemen; and running in from the right, a train of wild shadowy dancers

wild as demons. The horsemen are naked

on the four naked horses, and they make gestures as they come towards the

painted door. The horses are alternately red and black, the red having blue

manes and hoofs, the black, red ones, or white. They are tall archaic horses on

slim legs, with necks arched like a curved knife. And they come pinking daintily

and superbly along, with their long tails, towards the dark red death-door. From the left, the

stream of dancers leaps wildly, playing music, carrying garlands or wine-jugs,

lifting their arms like revellers, lifting their live knees, and signalling

with their long hands. Some have little inscriptions written near them: their

names. And above the false

door in the angle of the gable is a fine design: two black, wide-mouthed,

pale-maned lions seated back to back, their tails rising like curved stems,

between them, as they each one lift a black paw against the cringing head of a

cowering spotted deer, that winces to the deathblow. Behind each deer is a

smaller dark lion, in the acute angle of the roof, coming up to bite the

shrinking deer in the haunch, and so give the second death-wound. For the

wounds of death are in the neck and in the flank. At the other end of the

tomb are wrestlers and gamesters; but so shadowy now! We cannot see any more,

nor look any further in the shadows for the unconquerable life of the

Etruscans, whom the Romans called vicious, but whose life, in these tombs, is

certainly fresh and cleanly vivid. The upper air is wide

and pale, and somehow void. We cannot see either world any more, the Etruscan

underworld nor the common day. Silently, tired, we walk back in the wind to the

town, the old dog padding stoically behind. And the guide promises to take us

to the other tombs tomorrow. * * * There is a haunting

quality in the Etruscan representations. Those leopards with their long tongues

hanging out: those flowing hippocampi; those cringing spotted deer, struck in

flank and neck; they get into the imagination, and will not go out, And we see

the wavy edge of the sea, the dolphins curving over, the diver going down

clean, the little man climbing up the rock after him so eagerly. Then the men

with beards who recline on the banqueting beds: how they hold up the mysterious

egg! And the women with the conical head-dress, how strangely they lean

forward, with caresses we no longer know! The naked slaves joyfully stoop to

the wine-jars. Their nakedness is its own clothing, more easy than drapery. The

curves of their limbs show pure pleasure in life, a pleasure that goes deeper

still in the limbs of the dancers, in the big, long hands thrown out and

dancing to the very ends of the fingers, a dance that surges from within, like

a current in the sea. It is as if the current of some strong different life

swept through them, different from our shallow current today: as if they drew

their vitality from different depths that we are denied. Yet in a few centuries

they lost their vitality. The Romans took the life out of them. It seems as if

the power of resistance to life, self-assertion, and overbearing, such as the

Romans knew: a power which must needs be moral, or carry morality with it, as a

cloak for its inner ugliness: would always succeed in destroying the natural

flowering of life. And yet there still are a few wild flowers and creatures. The natural flowering

of life! It is not so easy for human beings as it sounds. Behind all the

Etruscan liveliness was a religion of life, which the chief men were seriously

responsible for. Behind all the dancing was a vision, and even a science of

life, a conception of the universe and man's place in the universe which made

men live to the depth of their capacity. To the Etruscan all was

alive; the whole universe lived; and the business of man was himself to live

amid it all. He had to draw life into himself, out of the wandering huge

vitalities of the world. The cosmos was alive, like a vast creature. The whole

thing breathed and stirred. Evaporation went up like breath from the nostrils

of a whale, steaming up. The sky received it in its blue bosom, breathed it in

and pondered on it and transmuted it, before breathing it out again. Inside the

earth were fires like the heat in the hot red liver of a beast. Out of the

fissures of the earth came breaths of other breathing, vapours direct from the

living physical underearth, exhalations carrying inspiration. The whole thing

was alive, and had a great soul, or anima: and in spite of one great

soul, there were myriad roving, lesser souls: every man, every creature and tee

and lake and mountain and stream, was animate, had its own peculiar

consciousness. And has it today. The cosmos was one, and

its anima was one; but it was made up of creatures. And the greatest

creature was earth, with its soul of inner fire. The sun was only a reflection,

or off-throw, or brilliant handful, of the great inner fire. But in juxtaposition

to earth lay the sea, the waters that moved and pondered and held a deep soul

of their own. Earth and waters lay side by side, together, and utterly

different. So it was. The

universe, which was a single aliveness with a single soul, instantly changed,

the moment you thought of it, and became a dual creature with two souls, fiery

and watery, for ever mingling and rushing apart, and held by the great

aliveness of the universe in an ultimate equilibrium. But they rushed together

and they rushed apart, and immediately they became myriad: volcanoes and seas,

then streams and mountains, trees, creatures, men. And everything was dual, or

contained its own duality, for ever mingling and rushing apart. The old idea of the

vitality of the universe was evolved long before history begins, and elaborated

into a vast religion before we get a glimpse of it. When history does begin, in

China or India, Egypt, Babylonia, even in the Pacific and in aboriginal

America, we see evidence of one underlying religious idea: the conception of

the vitality of the cosmos, the myriad vitalities in wild confusion, which

still is held in some sort of array: and man, amid all the glowing welter,

adventuring, struggling, striving for one thing, life, vitality, more vitality:

to get into himself more and more of the gleaming vitality of the cosmos. That

is the treasure. The active religious idea was that man, by vivid attention and

subtlety and exerting all his strength, could draw more life into himself, more

life, more and more glistening vitality, till he became shining like the

morning, blazing like a god. When he was all himself he painted himself

vermilion like the throat of dawn, and was god's body, visibly, red and utterly

vivid. So he was a prince, a king, a god, an Etruscan Lucumo; Pharaoh, or

Belshazzar, or Ashurbanipal, or Tarquin; in a feebler decrescendo,

Alexander, or Caesar, or Napoleon. This was the idea at

the back of all the great old civilizations. It was even, half-transmuted, at

the back of David's mind, and voiced in the Psalms. But with David the living

cosmos became merely a personal god. With the Egyptians and Babylonians and

Etruscans, strictly there were no personal gods. There were only idols or

symbols. It was the living cosmos itself, dazzlingly and gaspingly complex,

which was divine, and which could be contemplated only by the strongest soul,

and only at moments. And only the peerless soul could draw into itself some

last flame from the quick. Then you had a king-god indeed. There you have the

ancient idea of kings, kings who are gods by vividness, because they have

gathered into themselves core after core of vital potency from the universe,

till they are clothed in scarlet, they are bodily a piece of the deepest fire.

Pharaohs and kings of Nineveh, kings of the East, and Etruscan Lucumones, they

are the living clue to the pure fire, to the cosmic vitality. They are the

vivid key to life, the vermilion clue to the mystery and the delight of death

and life. They, in their own body, unlock the vast treasure-house of the cosmos

for their people, and bring out life, and show the way into the dark of death,

which is the blue burning of the one fire. They, in their own bodies, are the

life-bringers and the death-guides, leading ahead in the dark, and coming out in

the day with more than sunlight in their bodies. Can one wonder that such dead

are wrapped in gold; or were? The life-bringers, and

the death-guides. But they set guards at the gates both of life and death. They

keep the secrets, and safeguard the way. Only a few are initiated into the

mystery of the bath of life, and the bath of death: the pool within pool within

pool, wherein, when a man is dipped, he becomes darker than blood, with death,

and brighter than fire, with life; till at last he is scarlet royal as a piece

of living life, pure vermilion. The people are not

initiated into the cosmic ideas, nor into the awakened throb of more vivid

consciousness. Try as you may, you can never make the mass of men throb with

full awakenedness. They cannot be more than a little aware. So you must

give them symbols, ritual and gesture, which will fill their bodies with life

up to their own full measure. Any more is fatal. And so the actual knowledge

must be guarded from them, lest knowing the formulae, without undergoing at all

the experience that corresponds, they may become insolent and impious, thinking

they have the all, when they have only an empty monkey-chatter. The esoteric

knowledge will always be esoteric, since knowledge is an experience, not a

formula. But it is foolish to hand out the formulae. A little knowledge is

indeed a dangerous thing. No age proves it more than ours. Monkey-chatter is at

last the most disastrous of all things. The clue to the

Etruscan life was the Lucumo, the religious prince. Beyond him were the priests

and warriors. Then came the people and the slaves. People and warriors and

slaves did not think about religion. There would soon have been no religion

left. They felt the symbols and danced the sacred dances. For they were always

kept in touch, physically, with the mysteries. The 'touch' went from the

Lucumo down to the merest slave. The blood-stream was unbroken. But 'knowing'

belonged to the high-born, the pure-bred. So, in the tombs we

find only the simple, uninitiated vision of the people. There is none of the

priest-work of Egypt. The symbols are to the artist just wonderforms, pregnant

with emotion and good for decoration. It is so all the way through Etruscan

art. The artists evidently were of the people, artisans. Presumably they were

of the old Italic stock, and understood nothing of the religion in its

intricate form, as it had come in from the East: though doubtless the crude

principles of the official religion were the same as those of the primitive

religion of the aborigines. The same crude principles ran through the religions

of all the barbaric world of that time, Druid or Teutonic or Celtic. But the

newcomers in Etruria held secret the science and philosophy of their religion,

and gave the people the symbols and the ritual, leaving the artists free to use

the symbols as they would; which shows that there was no priest-rule. Later, when scepticism

came over all the civilized world, as it did after Socrates, the Etruscan

religion began to die, Greeks and Greek rationalism flooded in, and Geek

stories more or less took the place of the old Etruscan symbolic thought. Then

again the Etruscan artists, uneducated, used the Greek stories as they had used

the Etruscan symbols, quite freely, making them over again just to please themselves. But one radical thing

the Etruscan people never forgot, because it was in their blood as well as in

the blood of their masters: and that was the mystery of the journey out of

life, and into death; the death-journey, and the sojourn in the afterlife. The

wonder of their soul continued to play round the mystery of this journey and

this sojourn. In the tombs we see it;

throes of wonder and vivid feeling throbbing over death. Man moves naked and

glowing through the universe. Then comes death: he dives into the sea, he

departs into the underworld. The sea is that vast

primordial creature that has a soul also, whose inwardness is womb of all

things, out of which all things emerged, and into which they are devoured back.

Balancing the sea is the earth of inner fire, of after-life, and before-life.

Beyond the waters and the ultimate fire lay only that oneness of which the

people knew nothing: it was a secret the Lucumones kept for themselves, as they

kept the symbol of it in their hand. But the sea the people knew.

The dolphin leaps in and out of it suddenly, as a creature that suddenly

exists, out of nowhere, He was not: and to! there he is! The dolphin which

gives up the sea's rainbows only when he dies. Out he leaps; then, with a

head-dive, back again he plunges into the sea. He is so much alive, he is like

the phallus carrying the fiery spark of procreation down into the wet darkness

of the womb. The diver does the same, carrying like a phallus his small hot

spark into the deeps of death. And the sea will give up her dead like dolphins

that leap out and have the rainbow within them. But the duck that swims

on the water, and lifts his wings, is another matter: the blue duck, or goose,

so often represented by the Etruscans. He is the same goose that saved Rome, in

the night. The duck does not live

down within the waters as the fish does. The fish is the anima, the

animate life, the very clue to the vast sea, the watery element of the first

submission. For this reason Jesus was represented in the first Christian centuries

as a fish, in Italy especially, where the people still thought in the Etruscan

symbols. Jesus was the anima of the vast, moist ever-yielding element

which was the opposite and the counterpart of the red flame the Pharaohs and

the kings of the East had sought to invest themselves with. But the duck has no

such subaqueous nature as the fish. It swims upon the waters, and is

hot-blooded, belonging to the red flame, of the animal body of life. But it

dives under water, and preens itself upon the flood. So it became, to man, the

symbol of that part of himself which delights in the waters, and dives in, and

rises up and shakes its wings. It is the symbol of a man's own phallus and

phallic life. So you see a man holding on his hand the hot, soft, alert duck,

offering it to the maiden. So today the Red Indian makes a secret gift to the

maiden of a hollow, earthenware duck, in which is a little fire and incense. It

is that part of his body and his fiery life that a man can offer to a maid. And

it is that awareness or alertness in him, that other consciousness, that wakes

in the night and rouses the city. But the maid offers the

man a garland, the rim of flowers from the edge of the 'pool', which can be

placed over the man's head and laid on his shoulders, in symbol that he is

invested with the power of the maiden's mystery and different strength, the

female power. For whatever is laid over the shoulders is a sign of power added. Birds fly portentously

on the walls of the tombs. The artist must often have seen these priests, the

augurs, with their crooked, bird-headed staffs in their hand, out on a high

place watching the flight of larks or pigeons across the quarters of the sky.

They were reading the signs and the portents, looking for an indication, how

they should direct the course of some serious affair. To us it may seem

foolish. To them, hot-blooded birds flew through the living universe as

feelings and premonitions fly through the breast of a man, or as thoughts fly

through the mind. In their flight the suddenly roused birds, or the steady,

far-coming birds, moved wrapped in a deeper consciousness, in the complex

destiny of all things. And since all things corresponded in the ancient world,

and man's bosom mirrored itself in the bosom of the sky, or vice versa,

the birds were flying to a portentous goal, in the man's breast who watched, as

well as flying their own way in the bosom of the sky. If the augur could see

the birds flying in his heart, then he would know which way destiny too

was flying for him. The science of augury

certainly was no exact science. But it was as exact as our sciences of

psychology or political economy. And the augurs were as clever as our

politicians, who also must practise divination, if ever they are to do anything

worth the name. There is no other way when you are dealing with life. And if

you live by the cosmos, you look in the cosmos for your clue. If you live by a

personal god, you pray to him. If you are rational, you think things over. But

it all amounts to the same thing in the end. Prayer, or thought, or studying

the stars, or watching the flight of birds,-or studying the entrails of the

sacrifice, it is all the same process, ultimately: of divination. All it

depends on is the amount of true, sincere, religious concentration you can

bring to bear on your object. An act of pure attention, if you are capable of

it, will bring its own answer. And you choose that object to concentrate upon

which will best focus your consciousness. Every real discovery made, every

serious and significant decision ever reached, was reached and made by

divination. The soul stirs, and makes an act of pure attention, and that is a

discovery. The science of the

augur and the haruspex was not so foolish as our modern science of political

economy. If the hot liver of the victim cleared the soul of the haruspex, and

made him capable of that ultimate inward attention which alone tells us the

last thing we need to know, then why quarrel with the haruspex? To him, the

universe was alive, and in quivering rapport. To him, the blood was

conscious: he thought with his heart. To him, the blood was the red and shining

stream of consciousness itself. Hence, to him, the liver, that great organ

where the blood struggles and 'overcomes death', was an object of profound mystery

and significance. It stirred his soul and purified his consciousness; for it

was also his victim. So he gazed into the hot liver, that was mapped out in

fields and regions like the sky of stars, but these fields and regions were

those of the red, shining consciousness that runs through the whole animal

creation. And therefore it must contain the answer to his own blood's question. It is the same with the

study of stars, or the sky of stars. Whatever object will bring the

consciousness into a state of pure attention, in a time of perplexity, will

also give back an answer to the perplexity. But it is truly a question of divination.

As soon as there is any pretence of infallibility, and pure scientific

calculation, the whole thing becomes a fraud and a jugglery. But the same is

true not only of augury and astrology, but also of prayer and of pure reason,

and even of the discoveries of the great laws and principles of science. Men

juggle with prayer today as once they juggled with augury; and in the same way

they are juggling with science. Every great discovery or decision comes by an

act of divination. Facts are fitted round afterwards. But all attempt at

divination, even prayer and reason and research itself, lapses into jugglery

when the heart loses its purity. In the impurity of his heart, Socrates often

juggled logic unpleasantly. And no doubt, when scepticism came over the ancient

world, the haruspex and the augur became jugglers and pretenders. But for

centuries they held real sway. It is amazing to see, in Livy, what a big share

they must have had in the building up of the great Rome of the Republic. Turning from birds to

animals, we find in the tombs the continual repetition of lion against deer. As

soon as the world was created, according to the ancient idea, it took on

duality. All things became dual, not only in the duality of sex, but in the

polarity of action. This is the 'impious pagan duality'. It did not, however,

contain the later pious duality of good and evil. The leopard and the

deer, the lion and the bull, the cat and the dove, or the partridge, these are

part of the great duality, or polarity of the animal kingdom. But they do not

represent good action and evil action. On the contrary, they represent the

polarized activity of the divine cosmos, in its animal creation. The treasure of

treasures is the soul, which, in every creature, in every tree or pool, means

that mysterious conscious point of balance or equilibrium between the two

halves of the duality, the fiery and the watery. This mysterious point clothes

itself in vividness after vividness from the right hand, and vividness after

vividness from the left. And in death it does not disappear, but is stored in

the egg, or in the jar, or even in the tree which brings forth again. But the soul itself,

the conscious spark of every creature, is not dual; and being the immortal, it

is also the altar on which our mortality and our duality is at last sacrificed. So as the key-picture

in the tombs, we have over and over again the heraldic beasts facing one

another across the altar, or the tree, or the vase; and the lion is smiting the

deer in the hip and the throat. The deer is spotted, for day and night, the

lion is dark and light the same. The deer or lamb or

goat or cow is the gentle creature with udder of overflowing milk and

fertility; or it is the stag or ram or bull, the great father of the herd, with

horns of power set obvious on the brow, and indicating the dangerous aspect of

the beasts of fertility. These are the creatures of prolific, boundless

procreation, the beasts of peace and increase. So even Jesus is the lamb. And

the endless, endless gendering of these creatures will fill all the earth with

cattle till herds rub flanks over all the world, and hardly a tree can rise

between. But this must not be

so, since they are only half, even of the animal creation. Balance must be

kept. And this is the altar we are all sacrificed upon: it is even death; just

as it is our soul and purest treasure. So, on the other hand

from the deer, we have lionesses and leopards. These, too, are male and female.

These, too, have udders of milk and nourish young; as the wolf nourished the

first Romans: prophetically, as the destroyers of many deer, including the

Etruscan. So these fierce ones guard the treasure and the gateway, which the prolific

ones would squander or close up with too much gendering. They bite the deer in

neck and haunch, where the great blood-streams run. So the symbolism goes all through the Etruscan

tombs. It is very much the symbolism of all the ancient world. But here it is

not exact and scientific, as in Egypt. It is simple and rudimentary, and the

artist plays with it as a child with fairy stories. Nevertheless, it is the

symbolic element which rouses the deeper emotion, and gives the peculiarly

satisfying quality to the dancing figures and the creatures. A painter like

Sargent, for example, is so clever. But in the end he is utterly uninteresting,

a bore. He never has an inkling of his own triviality and silliness. One

Etruscan leopard, even one little quail, is worth all the miles of him.

|