| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2024

(Return

to Web

Text-ures)

| Click

Here to return to The Elm Tree Fairy Book Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

THE

FAITHFUL STEWARD

FAR away in the Scotch Highlands, where the purple heather spreads as thick on the hills in summer as the snow lies white in winter, a powerful chief ruled his clan. Over hill and glen his domain spread far and wide, and many were the men to whom his name was law and who acknowledged him as their lord. Among the most trusted of his servants was the steward who had charge of his purse, his castle and his treasures. This steward was faithful to his chief, and his master had entire confidence in him; but the very fact that he was so faithful and so trusted was enough to create an overwhelming hatred in the heart of James the Bard, who was another of the chief's servants, and whom the chief depended on to play the bagpipes and sing songs whenever he wished such entertainment. The bard was ready to do anything to contrive his fellow-servant's downfall, and he often hinted to the chief that all was not right with John the Steward. There were two things on which the chief prided himself, more than on all else more than on his prowess in war, or on the extent of his domain, and power. These two things were his justice 'and the beauty of his wife. When James the Bard spoke scornfully of the steward, the chief would reply, "It's of no use to come howling to me finding fault with John. You show me that I have lost any of my grain, any of my gold, or any of my jewels, and then I'll investigate the matter. I am quite ready to attend to whatever accusation seems reasonable, for you know that I am a just man." Time went on, and James the Bard continued to watch for a chance to bring the steward low. At last he was walking up a lonely glen near the chief's castle, kicking at every root and stone that happened to be in his way, and giving vent to his feelings in many an envious groan. The year would come to an end in one day more, and on New Year's Day it was the custom for all the leading men of the clan to come together before their chief and offer homage and congratulations. John the Steward would then be in all his glory, and everyone would be impressed that he was the most important personage among the chief's servants. This made James the Bard ponder more desperately than ever. "Kera caw!" croaked a crow as the bard passed near it sighing and complaining, "What is the meaning of this ado? Have you eaten something that doesn't agree with you, or what is it that pains you so?"

James the Bard looked up and saw the crow. Its evil eyes showed that it had a heart as wicked as his own. So he told the story of his hatred of John the Steward and the difficulty he was having to contrive the steward's disgrace. "Is that all you are worrying about?" the crow responded. "Why don't you say he stole the chief's golden barley?" "Because I have no witness to support me in so saying," replied the bard. "What will you give me if I appear as a witness in your behalf?" asked the crow. "A measure of beans from my own garden and some sweetmeats which I will take from the chief's table!" eagerly exclaimed James the Bard. "Kera caw! I agree to that bargain," said the crow. "Bring the beans and the sweetmeats to me tomorrow. On New Year's Day, in the presence of the assembly, charge the steward with stealing the barley. After that call on me when I'm wanted and I'll come without fail." So the beans and sweetmeats were given, and the morn of the New Year arrived. A crowd filled the great hall of the castle as the folks came to deliver compliments to the chief and his lady, to make their reports and to receive orders. Jauntily among the rest moved James the Bard, and at length he pushed to the front and bowed before his master in low obeisance. "How now?" said the chief. "Any complaints? Any advice? Any wish? I am a just man. Say on without fear." "John the Steward has been stealing your golden barley, oh chief!" cried James the Bard, "and he should be put to death." "Have you any witnesses to swear that what you say is true?" asked the chief. "Remember I am a just man, and I must have proof." "I have for a witness a crow from a near glen who knows all about the theft," said James the Bard. "In that case, steward," said the chief turning toward the faithful John, "you must die." "Will not your highness call the witness and make sure of his truthfulness before condemning me?" asked the steward. "If I am guilty, I am ready to die. If I am innocent, your own justice forbids that I should suffer." "You are right," responded the chief. "Bard, call your witness." James the Bard threw open a window and whistled three times. A moment later the crow appeared and alighted on the window-sill. "Do you take oath, oh crow," said the chief, "that John the Steward stole my golden barley?" "I do," declared the crow. "But what makes you so sure?" the chief questioned. "Because," croaked the crow, without hesitation, "he gave me some of the barley to eat this very morning to keep me from telling you of his offence, for he knew I saw him steal it. Look you how my crop is distended, full, full, full!" "Ah I "exclaimed the chief, scowling at the steward, "you must certainly die!" "I pray that you will have the witness cut open and see if it speaks the truth," said John the steward. "Do so," commanded the chief, "for I am a just man." Then the crow was killed and cut open, and they found nothing in its crop but some sugar and a handful of beans. They threw the carcass out of the window into the lake below, and Spottie Face, the great salmon who had his residence there, swallowed it- at one gulp. "This is nonsense!" roared the chief. "The case is dismissed. Let us go to supper." So the chief and his vassals went to supper, and in the delights of the feast-room they forgot all about the evil that was devised against the steward. If there was an angry man in the whole district that man was James the Bard. Failure did riot, however, make him give up his evil design, and he plotted the whole year through how he might bring John the Steward to the gallows. It was again two days before the New Year, and the bard was walking through the pine woods. He crushed the fallen cones savagely beneath his feet into the frosty ground, while from time to time he raised his voice in angry exclamation. Thus he went on till he was passing a cave where lived a witch, and the witch was sitting at the entrance of the cave. Within, burned a peat fire, and the blue reek whirled in puffs out of the cavern and kept the witch constantly blinking her eyes. She noted the bard's irritated manner and loud tones and she said, "What's all this to-do about?" James the Bard looked up, and as she appeared to be as evil as himself he lost no time in telling her how anxious he was to disgrace and get rid of John the Steward. "Why don't you say he stole the chief's gold?" she suggested. "But I can't get at the gold," replied the bard, "and even if I could get at it and should take some of it, I have no witness to swear that I speak the truth when I charge the steward with the theft." "I could tell you how to manage all that," said the witch. "What will you give me to have the sun appear as your witness?" "I will share with you whatever I am able to steal after the steward is out of the way," was the bard's answer. "Well, if we want the sun," said she, "I must brew iron's broth to attract him. Come here again tomorrow and the broth will be ready. On New Year's morning take it to the nearest hilltop, and at the moment the sun rises cast it on the ground toward the east. Thus you will make sure the sun will come that day as a witness to the council." So saying, the witch entered her cave, and James the Bard went away. But the next day he again visited the witch and she gave him a bowl filled with troll's broth, and told him all the things he must do to make it appear that the steward had stolen the chief's gold. He took the broth away and he did with it just as the witch had directed. With the coming of the New Year a large crowd gathered in the hall of the castle to offer congratulations to their chief and his wife and to eat the good things at their table. After many had spoken and much business had been transacted, James the Bard stepped forward. "How now?" said the chief. "If you have anything to say, speak. I am wearying for my supper. So be quick!" "Oh," responded James the Bard, pointing at the steward, "that fellow over there has been stealing your golden coins, and he should die!" "I am a just man," said the chief, "so I can't take your word for it alone, you know. Have you any witnesses? No crows or any of that crew for me this time, mind you " "Sir, I have for a witness none other than the sun himself," declared the bard. "Steward!" said the chief, "if that is so, you certainly must have your head chopped off." "Order him, I beg, to produce his witness," the steward humbly responded. "If I am guilty, then let me die." "I am a just man," said the chief. "So call the witness."  "Follow me, chief and gentlemen all," cried James the Bard. "We will go to the chamber above that looks toward the southwest, and there I will prove my accusation true." "Why to the chamber at the southwest?" the chief asked. "Because," replied the bard, "there the stolen money lies, and there my witness shall attend." "Lead on!" ordered the chief, "and hurry about it, for I am getting very hungry." So James the Bard led the way to the chamber looking toward the southwest, and as they entered the apartment, sure enough, the sunlight streamed in through the window and gleamed and glittered on many a golden coin that lay in rich confusion on the floor. "Headsman, do your duty!" exclaimed the chief pointing to John the Steward. "Sir chief," said the steward hastily, "I pray that before I die you will take up one of these coins and look at it carefully in the shade and make sure it really is gold." "I am a just man," said the chief. "Hand me one of those golden coins." They handed him a coin, and taking it into a corner out of the sunlight, he saw it was a common copper coin, and not a golden one at all. "If I had yon witness in my power," cried the chief, shaking his fist at the sun, "I'd thrash him! As for James the Bard his punishment shall come after supper." Then the chief took the arm of the steward and hurried away to the banqueting hall. He was so hungry he would have no more delay. That time again James the Bard escaped his merited punishment, for in the delights of the feast the evil of the day was forgotten. How savage the bard felt at his second failure to disgrace the steward you can well imagine. "I'll make the old witch suffer for this, at any rate!" said he, and full of wrath he sought the cavern and called loudly on its occupant to come forth. But when she appeared at the mouth of the cave, she looked so fierce that his courage oozed out of his finger-tips, and his angry words dwindled to a feeble whine of complaint. "Well," said the witch, "what brings you here again?" "The wretched failure of your scheme," answered the bard, and he related all that had occurred. "Whose fault was that?" she snarled. "It surely wasn't mine. But I have another plan. We will prove that the steward stole the chief's wine this time." "I can't prove it unless have a witness," said the bard. "The crow is dead, and the sun is of no use at all. What am I to do?" "We'll get the moon to be your witness," responded the witch; "but I must brew troll's broth or the thing can't be managed at all. Come for it the last day of the year and it will be ready for you." Then she told him all the things he must do to make it appear that John the Steward had stolen the wine, and he went his way. The year passed and on the evening of the appointed day, just as the shadows were creeping out of the pine woods and spreading over the hills and vales James the Bard came to the witch's cavern. He received in his hands the bowl of troll's broth that the witch had prepared, and she said, "Go to the crag near the castle where the dead fir spreads its bare branches to the sky. There, as the moon rises, walk three times around the decaying tree-trunk, and cast the broth on the ground toward the east."

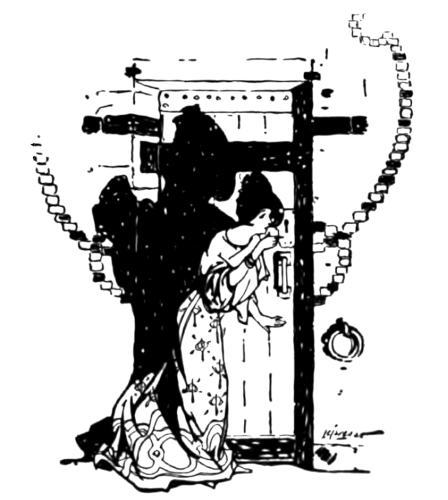

James the Bard went away to the crag, carrying the bowl of broth, and as the moon rose he walked thrice around the old tree and cast the broth toward her, bidding her come the next evening to be his witness when he should call. The following day all the chief's retainers and vassals flocked to the castle to give greeting and receive advice. Toward the day's end James the Bard came forward to make his statement. "Noble chief!" said he, "I am here to denounce that villain, John the Steward, and to ask that he be put to death." "I am a just man I "cried the chief, "and I will not condemn a person without proof or witness. Say on, but beware how you trifle with me this time." "He has stolen your wine, and I can prove it," declared James the Bard. "Stolen my wine! That must be put a stop to, and you," said the chief turning to the steward, "must be put an end to." "Oh chief," said the steward, "will you listen to my enemy without making certain that he speaks the truth?" "Nay," answered the chief, "such a course would be unworthy of my own justice. Where is your witness?" continued he, looking sharply at James the Bard. "The moon is my witness," replied the bard, "and none other. The deed was done in the night and she will come at eventide and give proof of it." "The moon be praised that she doesn't wish to come now!" ejaculated the chief, "for I want my supper." Without more ado the chief marched to the apartment where the feast was waiting, and in the delight of the repast soon forgot the business of the day. But when they had all drunk quite as much as was good for them, and had eaten, in my opinion, more than was necessary, James the Bard approached the chief and begged him to step up to the chamber in the northeast tower, for there his witness was waiting to prove his accusation. "Oh, bother!" exclaimed the chief, "I'm very comfortable here. I can't be climbing up those tower stairs. Cut the steward's head off. I don't care, and I don't want proof!" "Noble master," said John the Steward, "remember you are a just man." "Pest take the whole affair!" roared the chief, getting up. "I can't even finish my meals in peace. I suppose I must attend to this affair, but whoever trifles with me now is a dead man!" So, in a fume, he bounced off after James the Bard, kicking him occasionally from behind to make him move faster. He was followed by his lady and the rest of the vassals, who were all agog to see what would happen. When they arrived at the northeast tower and had entered the chamber, sure enough, they saw basins and goblets and beakers set about the floor and tables and all filled to overflowing with dark red wine. There could be no doubt about it at all, for the moon was shining in at the window, and the room was flooded with its light. "I have seen enough!" cried the chief. "Sword-bearer, give me my sword. Now, steward, down on your knees! You'll take my wine, will you? I'll have your head off! So you won't feel thirsty much longer!" "I beseech you, my lord," said John the Steward as he knelt before the chief, "that you will taste a drop of that wine. Grant me this one last request before I die. I will make no resistance. Only grant me this one little boon." "Well, it is more than you deserve, but I will do that, for I am a just man," replied the chief, taking up one of the cups and placing it to his lips. "Ah auch! phew! bah!" and with a fearful grimace he spat the liquid out on the floor. "Give me something to take the taste out of my mouth!" yelled the chief, "and seize James the Bard. He shall die at cockcrow tomorrow. Oh! ach! phew! I'm poisoned!" So saying he rushed out of the room, scattering everyone right and left. Down stairs he went three steps at a time and was rinsing and scouring out his mouth before anyone recovered from the start he had given them. But the chief was not poisoned after all, for the basins and goblets and beakers simply contained brown bog water that James the Bard had poured into them and that looked very ruddy in the moonlight. The bard was to be executed the next morning at cockcrow, and he was placed under lock and key in the dungeon, and a jailor was ordered to stand guard over him to make sure of his not escaping. But in some manner or other the bard contrived to get word sent to the chief's lady that he had a message of the deepest importance to confide to her, and that, though he must die, it was a pity so great a secret should be lost, especially when she could listen easily at the keyhole while he spoke to her from the other side of the door, and nobody would be any the worse, and nobody but she any the wiser.

The chief's lady was at first inclined to pay no attention to this message, but she could not restrain her curiosity, and at midnight she repaired to the door of the dungeon. After ordering the jailor to go away beyond earshot, she rapped on the oaken door and applied her ear to the keyhole. What James the Bard told the lady must have been of vast importance, and it seems to have been a secret the full explanation of which he could not give her for three days, inasmuch as she went straightway to the chief, her husband, and begged him to defer the execution of the bard for that length of time. The chief, who had now recovered his temper, consented after a little demur, for his wife was not only beautiful, but when her mind was set on anything he knew she would worry the inside out of a pig before she gave up. Yes, poor man! he knew this only too well from long experience. Hence his consent. After the first night the jailor put fetters on James the Bard and allowed him to go about the castle. He did not want to be bothered to sit opposite that dungeon three whole days, and he wanted also to be saved the trouble of carrying food to his prisoner. In spite of the doom that overhung the bard, revenge still burned in his heart. "Oh, that steward!" he exclaimed. "If I could only somehow bring about the fellow's disgrace I should die happy." It was evening of the first day that he had been allowed his liberty in the castle, and he sat crouched on a stairway thinking. Presently he happened to glance up, and the moon sailing in the frosty blue sky looked down at him through an open lattice. He called her an ugly name and continued his thinking. At last a novel and crafty idea struck him. He rose and with an evil grin on his face went to the dining-room and got a glass goblet from the table, and from a drawer a sharp-pointed awl. Then he climbed to a room up under the roof, went in, and after locking the door behind him sat down on a stool in front of the window. Next he closed the shutters which were of thin pine boards, and taking the awl he labored for two hours without ceasing to bore holes through the shutters, some large, some small. He pierced the holes in various scattered groups arranged to portray as best he could the sets of stars he had often noticed in the heavens.

Spottie Face, the

great salmon that had his residence in the pool below, swam to the surface and

looked up, expecting some food was about to be thrown to him. "Spottie Face! Oh Spottie Face!" continued James the Bard, "if I give you some sweetmeats from the chief's table, will you do me a favor?" Spottie Face was a mean-spirited fish and did not like doing favors for anybody; but it was winter and there was not much food. So Spottie Face put his nose above the water and waved assent with his tail. "Then take this key," said the bard, "and cast it up on the bank below the window of John the Steward. You know which his window is. The favor is not much to seek, you must allow. I will throw the sweetmeats to you from this window as soon as I can go to the banqueting hall and get them." So James the Bard tossed the key out to Spottie Face and went his way down the staircase. But Spottie Face, — when he had seized the key, found it was

bitter cold, for the frost had chilled the metal, and he spat it up on the bank

close to where he received it. There it lay a dark object on the snow under the

bard's own window. If the bard had looked sharply he might have seen it when he

returned and threw out the sweetmeats, but he never suspected that anything was

amiss, and his eyes were on Spottie Face, who swallowed the sweetmeats and then

sank to the bottom of the pool.  Now the fatal day arrived when James the Bard was to suffer for his deception of the chief. The jailor led him into the hall of the castle where all were assembled, and the chief and his wife sat in state to pass final judgment. "I am a just man," said the chief. "You have deceived me again and again, and you shall die now. That's settled!" "A boon I crave, one boon before I die!" cried James the Bard. "Let me but whisper a secret of the utmost value in your lady's ear." "You shall do nothing of the sort!" roared the chief. "Go and have your head cut off. I won't have any delay." But his good lady was not going to miss knowing that secret, whatever it might be. She had been thinking about it for the last three days and had fretted herself a good deal on the subject. So she gave her husband one of her looks, and he knew better than to say "No," when she looked "Yes." Then James the Bard whispered in her ear. "What! what! My jewels, my shining jewels!" screamed the lady, and she ran to John the Steward and shook her clenched fists in his astonished face. "Give me back my jewels, you thieving villain!" she cried. "Give back my shining jewels that you have stolen!" "What is all this fuss about?" asked the chief, jumping up from his chair of state. "Why, James the Bard says the steward has stolen my jewels," replied the lady. "Oh, husband dear, you must send John the Steward to the gallows at once!" "Hush! Softly, my love!" said he. "You are beautiful, but remember to be just also. The fact is, I don't believe a word you are saying, and I'll never put trust in James the Bard again, whether he has witnesses to prove his charges or not." "How many witnesses would make you believe my word?" asked the bard. "Will ten satisfy you?" "No!" shouted the chief. "Nothing under twenty. So be off and be hung!" "There are twenty and more witnesses at this moment waiting in the castle to prove that what I say is true!" cried the bard. The chief found he was caught, and knew that if he would keep up his character for justice he must consent to hear the case. "And who may these witnesses be?" he growled. "None other than the stars of heaven," was the bard's answer. "You are trying to play a low trick to escape your doom till the evening," said the chief. "Nay," the bard responded, "the stars are ready now to offer their testimony in the south attic; and what is more the jewels are there, too." "Come along, come along!" exclaimed the lady, seizing the chief by the sleeve, and the whole party, headed by James the Bard, made toward the door, for the chief saw he must go, Willy nilly, as his wife seemed quite out of her mind. "Where is the key?" said the bard when he arrived at the attic door and found it fast locked. "Yes, where is the key?" cried the chief. "Those who hide can find!" the bard declared, and pointing to John the Steward, added, "That fellow has it, of course. Search him. If you fail to find it you may be sure he has hid it in his chamber, and if it is not there he has cast it out of his window. Oh, I know his tricks!" "I am innocent," affirmed the steward, "and you may search as much as you please." So the steward was searched, and then his chamber was ransacked, and lastly one of the chief's followers looked out of the steward's window. "I see nothing of it," said he, "but wait there it is farther along on the bank." Sure enough, it was lying just under the chamber window belonging to James the Bard. They ran down and fetched it, and the bard nearly fainted with rage, for he saw that Spottie Face the salmon had deceived him. The door was opened, and there, without doubt, lay the jewels on the table and on the floor glittering in the light of the stars that shone brightly through the window into the darkened room. "My jewels! my jewels!" cried the chief's wife, running forward. "Oh steward," exclaimed the chief, shaking his head. "You must this time be put to death!" "Yes, yes "said his wife, "at once! at once! for he deserves it." "I pray you, noble chief," said the steward, question these witnesses and ask them what the truth is." "You are talking nonsense!" exclaimed the chief. "Why, they are thousands of miles away. How can they hear me?" "They are not further off than the other side of the window!" declared John the Steward. "Permit me to go and show you where they are." "Don't let him! Don't let him!" shrieked James the Bard. "You forget yourself!" thundered the chief, "and you forget that I am a just man. Steward, go to the window." Then the steward went to the casement and flung the shutters wide, and the bright daylight filled the chamber. All put up their hands to their eyes, for they were dazzled at the sudden change. "Dear lady," said the steward, "look now at your jewels. You see they are nothing but glass, and where are my enemy's witnesses?" "Steward, forgive me and all of us!" said the chief, coming forward, and giving him his hand. "We will never distrust you again as long as we live. Ask me any favor, and it shall be granted." "Then give me the life of James the Bard! cried the steward, "for I am the happiest man today in the country. I would have none sorrow while I am glad." "I grant your request on one condition," answered the chief. "Bard, stand forth. Swear, with both hands uplifted, that you will never more try to give false-witness, and I will spare your life." James the Bard stepped forward, flung both his arms over his head and promised as the chief wished. "Now," said the chief, "leave my sight and get out of the castle. I never want to set eyes on you again." "My dear," remarked the chief's wife to her husband as James the Bard departed, "I think you are as clever as you are just," and she gave him a good kiss on his right cheek. "And you, my love," said he, vastly pleased, "are as sensible as you are beautiful." With these words he gave her a good kiss on her left cheek,

which was very nice of him, don't you think, for turn and turn about is fair

play, isn't it? |

This done, he broke the goblet into small pieces, and

strewing the fragments on the table beneath the closed window shutters, and on

the floor near by, he left the room, locked the door and took the key away with

him. Now he went to his own room which was on the side of the castle next to

the lake. Opening the window he stretched his neck out as far as possible. The

foundations of the castle were only separated by a narrow strip of bank from

the deep water of the lake, and he began to call, "Spottie Face! Spottie

Face! Spottie Face! Come hither!"

This done, he broke the goblet into small pieces, and

strewing the fragments on the table beneath the closed window shutters, and on

the floor near by, he left the room, locked the door and took the key away with

him. Now he went to his own room which was on the side of the castle next to

the lake. Opening the window he stretched his neck out as far as possible. The

foundations of the castle were only separated by a narrow strip of bank from

the deep water of the lake, and he began to call, "Spottie Face! Spottie

Face! Spottie Face! Come hither!"