| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2024

(Return

to Web

Text-ures)

| Click

Here to return to The Elm Tree Fairy Book Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

WHITTINGTON

AND HIS CAT

Dick was a bright boy and he was always listening when

others talked. He liked especially to hear the chat of the farmers on Sunday

while they stood about in the churchyard before the parson came. In this manner

he heard many strange things about the great city of London, for the country

people at that time thought folks in London were all fine ladies and gentlemen,

and that there was singing and music in the city all day long, and that the

streets were paved with gold. One morning a large wagon drawn by eight horses passed

through the village. Dick was standing near an inn where the driver stopped for

a few minutes, and he heard someone say the wagon was going to London. So when

the driver came out of the inn he said to him, "Please, sir, will you let

me walk with you to London by the side of your wagon ?" "But what will your father and mother say?" asked

the driver. "I have no father and mother, now," replied Dick,

"nor is there anyone who would care whether I went or stayed." When the wagoner heard that and saw by the boy's ragged

clothes that he could not be worse off than he was, he told him he could go,

and off they trudged together. It was a long distance, but good-natured people

in the towns they passed through gave the boy something to eat, and at night

the driver let him get into the wagon to sleep among the boxes and parcels. Dick arrived safely on the outskirts of London and was in

such a hurry to see the fine streets all paved with gold, that he did not stay

even to thank the wagoner, but ran on as fast as his legs would carry him,

going from one street to another and constantly expecting the next one would be

paved with gold. He thought he would have nothing to do but take up some bits

of the pavement and then he would have as much money as he could wish for. Poor Dick ran on till he was tired. At last, finding that it

was growing dark, and that every way he turned he saw nothing but dirt instead

of gold he sat down in a dark corner and cried himself to sleep. There he stayed all night, and the next morning, being very

hungry, he got up and walked about asking everybody he met to give him a

halfpenny that he might buy food to keep him from starving. But no one paid any

attention to him except a man who said crossly, "You are an idle

rogue." He wished himself back in the country, where he knew he

could find shelter in a good kitchen and sit by a warm fire, and where he was

at least sure of enough to eat so that he would not starve. At last he sat down

very sorrowful, and faint for lack of food at the door of Mr. Fitzwarren a rich

merchant. Soon the cook spied him. She was an ill-tempered creature, and

happened to be very busy getting dinner for her master and mistress. "What business have you there, you young rascal?"

she called out to poor Dick. "We want no beggars hanging around this

house, and if you do not take yourself away, I will see how you like a sousing

of dish-water. I have some here hot enough to make you jump." Just then Mr. Fitzwarren came home to dinner. He saw the

dirty, ragged boy and said, "Why are you here, my boy? You seem old enough

to work. I am afraid you are inclined to be lazy." "No, indeed, sir," said Dick earnestly, "that

is not the case, for I would work with all my heart if I could find work to do.

But now I can hardly stand up for lack of food." "Poor fellow!" said the gentleman, "come into

the house and we will see what we can do for you." So the kind merchant had the lad accompany him to the

kitchen and ordered that a good dinner should be given him and that he be kept

to do such work as he was able to do in helping the cook. Little Dick would have lived very happy in this good family

if the cook had not been so cross. She used to say, "You are under me, and

you must keep busy. Clean the kettles and the dripping-pan, make the fires,

wind the clock, and do all the other kitchen work nimbly or " — and she

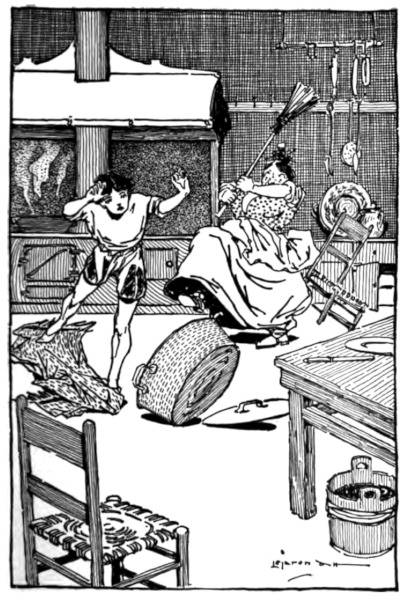

would shake the ladle at him. She was finding fault and scolding him from morning to

night, and sometimes she would whack him over the head with a broom. At length

her ill-usage of him was observed by Mr. Fitzwarren's daughter Alice, who was

about Dick's age, and she told the cook she would complain to her father and

have her discharged if she did not treat him more kindly. That made the cook behave a little better, but Dick had

still another hardship to endure. His bed was in a garret, and every night he

was tormented with rats and mice. They ran over his face and disturbed him with

their squeaking. He could think of no way to help matters until one day a

gentleman who was visiting at the house gave him a penny for cleaning his

shoes. "Ah," said Dick, "I wonder if I could not buy a cat with

this money."

Not long afterward he saw a girl passing with a cat in her arms, and he ran out and said, "Will you let me have that cat for a penny?" "Yes, surely I will," she replied, "and you

will find it an excellent mouser." Dick hid his cat in the garret and always took care to carry

a part of his dinner to it. In a short time he had no more trouble with the

rats and mice and could sleep every night. It presently happened that Dick's master had a ship ready to

sail, and as it was his custom to allow all his servants to have a chance to

profit by the ship's good fortune, he called them into the parlor and asked

them what money they would invest on this voyage. Dick had not a farthing in

the world, and therefore he stayed in the kitchen, but all the rest gathered as

requested and each was glad to venture something. Then Miss Alice asked for

Dick and had him brought in. "If you have no money," said she, "I

will let you have some from my own purse." "That will not do," said her father, "for

whatever he sends must be his own." When Dick heard this, he said, "I have nothing of my

own but a cat which I bought some time since with a penny a gentleman gave

me." "Fetch your cat then, my lad," said Mr.

Fitz-warren, "and it shall go in the ship." Dick went upstairs, and with tears in his eyes brought down

pussy and gave it to the captain. "I'm sorry to have the cat go," he

sighed, "for I shall now be kept awake all night by the rats and

mice." However, Miss Alice, who felt pity for him, gave him some

money to buy another cat. This and many other marks of kindness shown him by

Miss Alice made the ill-tempered cook jealous of Dick, and she began to use him

more cruelly than ever, and often made sport of him for sending his cat to sea.

"Why," said she, "your cat won't sell for as much money as would

buy a stick with which to beat you."

While he was thinking, the bells of Bow Church back in the

city began to ring, and their sound seemed to say to him, "Turn again, Whittington, Thrice Lord Mayor of London." "Lord Mayor of London!" said he to himself. "Why,

I would put up with almost anything if, when I grow to be a man, I could be

Lord Mayor of London, and ride in a fine coach. Well, I will go back and bear

the cuffing and scolding of the old cook as best I can." Dick returned as quickly as he could and was lucky enough to

get into the house and start about his usual drudgery before the cook came

down- stairs. The cat Dick sent with the Unicorn, as his master's ship was

called, voyaged to the coast of Africa, and the vessel was driven by contrary

winds to a part of the Barbary coast where the only people were Moors whom the

English had never known before. They came in great numbers to see the sailors,

who were so different from them in color and dress as to arouse their

curiosity. However, they were very civil, and when they became better

acquainted, were eager to buy the fine things with which the ship was loaded. The captain sent presents to the king of the country, who

was so much pleased with them that he invited the captain and his officers to

come to the palace. A feast was prepared, but they had scarcely sat down to eat

when a multitude of rats and mice rushed in, and the ravenous creatures

devoured much of the food in spite of all efforts to drive them away. "It seems to me," said the captain, "that

these rats and mice are quite unpleasant." "Yes," the king agreed, "they are very

offensive, and I would give half my treasure to be freed of them. They not only

destroy my dinner, but they assault me in my chamber, and even in bed, so that

I am obliged to be guarded while I am sleeping for fear of them." The captain remembered Whittington's cat and told the king

he had a creature on board the ship that would dispatch all 'the vermin

immediately. On hearing this, the king was jubilant and he jumped so high that

his turban dropped off. "Bring the creature to me," said he, "and

if it will do what you say I will give you a fortune in exchange for it." "We should miss the cat very much," said the

captain, "for when it is gone the rats and the mice will have their own

way in our ship." "Run, run!" ordered the queen. "I am

impatient to see the dear creature." Off went the captain to the ship, where he took puss under

his arm and at once started to return. He arrived at the palace just in time to

see the rats and mice once more rush in to the table which had been spread with

another feast. The cat promptly scrambled away from the captain, pounced on

them, and in a few minutes many of the pests lay dead on the floor, and the

rest in great fright scampered off to their holes. The king and queen were quite charmed to get rid so easily

of such plagues, and desired that the cat might be brought to them for

inspection, as no creature like it had hitherto been seen in their country.

Then the captain called, "Pussy, pussy, pussy!" and it at once came

to him. He carried it to the queen, but she started back and was

afraid to touch a creature which made such a havoc among the rats and mice.

However, she soon gained more confidence, and he put it down on her lap where

it began purring and sang itself to sleep. The king was so well satisfied with the cat's exploits that

he gave for it a cabinet of jewels worth ten times as much as the captain

received for all the merchandise in his vessel. Yet the cargo also was disposed

of to great advantage. In exchange the captain received goods of that country

and he was soon ready to return to England. The sails were set, and with a fair

wind the ship headed toward the open sea, and after a pleasant voyage arrived

in London. One morning Mr. Fitzwarren had just come to his

counting-house and seated himself at his desk when somebody rapped at the door.

"Who is there?" asked Mr. Fitzwarren. "A friend," was the answer. "I come to bring

you good tidings of your ship Unicorn." The merchant bustled up in a great hurry, and when he opened

the door, who should he see waiting but the ship's captain with a cabinet of

jewels and a list of the vessel's merchandise. Mr. Fitzwarren looked at the

list and lifting his eyes thanked Heaven for sending the Unicorn such a

prosperous voyage. Then the captain told the story of the cat and showed the

rich present that the king had given in exchange for it. As soon as the

merchant had heard what the captain had to say and had examined the jewels, he

called out to his servants, "Go send for Dick, and tell him of his fame, And call him Mr. Whittington by name." Some of the servants declared that so great a treasure was

too much for him, but Mr. Fitzwarren answered, "God forbid that I should

deprive him of the value of a single penny. It is all his own." Dick was found scouring the pots for the cook, and he tried

to excuse himself from going to the counting-house, saying, "The room is

not swept and my shoes are dirty and full of hobnails." But the servants took him along with them, and when they

entered the counting-house Mr. Fitz-warren ordered a chair to be set for him.

Dick began to think they were making game of him, and he said, "Please

don't play any tricks on me, but let me go back to my work." "Indeed, Mr. Whittington," said the merchant,

"we are very much in earnest, and I most heartily rejoice in the news that

the captain has brought you. He sold your cat to the King of Barbary, and

received in exchange more riches than I possess in the whole world. I wish you

may long enjoy them." Then the treasure was shown to him,. and Dick hardly knew

how to behave for joy. He begged his master to take what part of it he pleased,

since he owed it all to his kindness. "No, no," responded Mr. Fitzwarren, "it is

all yours, and I have no doubt you will use it well." However, Dick was too kind-hearted to keep it all to

himself, and he made generous presents to the captain and his crew and to his

fellow-servants in the house — even to the ill-natured old cook. By Mr. Fitzwarren's advice he went to a tailor to get

himself dressed like a gentleman, and when his new clothes were on and his hair

curled, he was as handsome and attractive as any lad in London. He also gained

in confidence, and by the time he was a young man had dropped that sheepish

behavior which had been largely the result of low spirits. In truth, he became

so sprightly and pleasant a companion that Miss Alice fell in love with him,

and at length they were married. Mr. Whittington and his lady lived in great splendor to a

good old age, and were very happy. He became Sheriff of London, was three times

Lord Mayor, and received the honor of knighthood from the king. |