|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Birds Every Child Should Know Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Birds Every Child Should Know Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER XIII

NON-UNION CARPENTERS

DOWNY WOODPECKER HAIRY WOODPECKER YELLOW-BELLIED SAPSUCKER RED-HEADED WOODPECKER FLICKER OUR FIVE COMMON WOODPECKERS IF, AS you walk through some old orchard or along the borders of a woodland tangle, you see a high-shouldered, stocky bird clinging fast to the side of a tree " as if he had been thrown at it and stuck," you may be very sure he is a woodpecker. Four of our five common, non-union carpenters wear striking black and white suits, patched or striped, the males with red on their heads, their wives with less of this jaunty touch of colour perhaps, or none, but wearing otherwise similar clothes. Only the dainty little black and white creeping warbler could possibly be confused with the smallest of these sturdy, matter-of-fact artisans, although, as you know, chickadees, titmice, nuthatches and kinglets also haunt the bark of trees; but the largest of these is smaller than downy, the smallest of the woodpeckers. One of the carpenters, the big flicker, an original fellow, is dressed in soft browns, yellow, white and black, with the characteristic red patch across the back of his neck. It is easy to tell a woodpecker at sight or even beyond it, when you see or hear him hammering for a dinner, or drumming a love song, or chiselling out a home in some partly decayed tree. How cheerfully his vigorous taps resound! Hammer, chisel, pick, drill, and drum-all these instruments in one stout bill-and a flexible barbed spear for a tongue that may be run out far beyond his bill, like the hummingbird's, make the woodpecker the best-equipped workman in the woods. All the other birds that pick insect eggs, grubs, beetles and spiders from the bark could go all over a tree and feast, but the woodpecker might follow them and still find plenty left, borers especially, hidden so deep that only his sticky, barbed tongue could drag them out. As you see his body flattened against the tree's side perhaps you wonder why he doesn't fall off. Do you remember why the swifts, that sleep against the inside walls of our chimneys, do not fall down to the hearths below? Like them and the bobolink, the woodpeckers prop themselves by their outspread, stiffened tails: Moreover, they have their toes arranged in a curious way-two in front and two behind, so that they can hold on to a section of bark very much as an iceman holds a piece of ice between his tongs. Smooth bark conceals no larvae nor does it offer a foothold, which is why you are likely to see woodpeckers only on the trunks or the larger limbs of trees where old, scaly bark grows.

DOWNY WOODPECKER

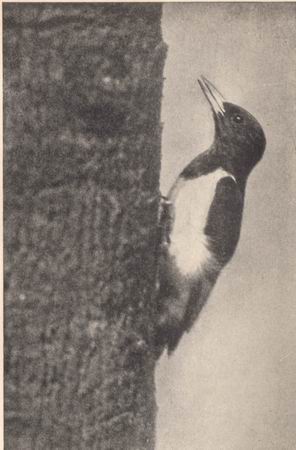

A hardy little friend is the downy woodpecker who, like the chickadee, stays by us the year around. Probably no other two birds are so useful in our orchards as these, that keep up a tireless search for the insect robbers of our fruit. Wintry weather can be scarcely too severe for either, for both wear a warm coat of fat under their skins and both have the comfort of a snug retreat when bitter blasts blow. Friend downy is too good a carpenter, you may be sure, to neglect making a cozy cavity for himself in autumn, just as the hairy woodpecker does. The chickadee, titmouse, nuthatch, bluebird, wren, tree swallow, sparrow hawk, crested flycatcher and owls, are not the only birds that are thankful to occupy his snug quarters in some old tree after he has moved out in the spring to the new nursery that his mate and he make for their family. He knows the advantage of a southern exposure for his hollow home and chisels his winter quarters deep enough to escape a draught. Here he lives in single blessedness -- or selfishness? -- with no thought now for the comfort of his mate, who, happily, is quite as good a carpenter as he, and as able to care for herself. She may make a winter home or keep the nursery. Very early in the spring you will hear the downy, like the other woodpeckers, beating a rolling tattoo on some resonant limb, and if you can creep close enough you will see his head hammering so fast that there is only a blur above his shoulders. This drumming is his love song. The grouse is even a more wonderful performer, for he drums without a drum, which no woodpecker can do. The woodpecker drums not only to win a mate, however, but to tell where a tree is decayed and likely to be an easy spot to chisel, and also to startle borers beneath the bark, that he may know just where to tunnel for them, when they move with a faint noise, which his sharp ears instantly detect. This master workman, who is scarcely larger than an English sparrow, occasionally pauses in his hammering long enough to utter a short, sharp peek, peek, often continued into a rattling cry that ends as abruptly as it began. You may know him from his larger and louder-voiced cousin, the hairy woodpecker, not only by this call note, but by the markings of the outer tail feathers, which, in the downy, are white barred with black; and in the hairy, are white without the black bars. Both birds are much striped and barred with black and white. When the weather grows cold, hang a bone with a little meat on it, cooked or raw, or a lump of suet in some tree beyond the reach of cats; then watch for the downy woodpecker's and the chickadee's visits to your free-lunch counter.  Our little friend downy

The red-headed woodpecker

HAIRY WOODPECKER

Light woods, with plenty of old trees in them, suit this busy carpenter better than orchards or trees close to our homes, for he is more shy than his sociable little cousin, downy, whom he as closely resembles in feathers as in habits. He is three inches longer, however, yet smaller than a robin. In spite of his name, he is covered with black and white feathers, not hairs. He has a hairy stripe only down the middle of his broadly striped back. After he and his mate have decided to go to housekeeping, they select a tree -- a hollow-hearted or partly decayed one is preferred -- and begin the hard work of cutting out a deep cavity. Try to draw freehand a circle by making a series of dots, as the woodpecker outlines his round front door, and see, if you please, whether you can make so perfect a ring. Downy's entrance need be only an inch and a half across; the hairy's must be a little larger, and the flicker requires a hole about four inches in diameter to admit his big body. Both mates work in turn at the nest hole. How the chips fly! Braced in position by stiff tail feathers and clinging by his stout toes, the woodpecker keeps hammering and chiselling at his home more hours every day than a labour union would allow. Two inches of digging with his strong combination tool means a hard day's work. The hole usually runs straight in for a few inches, then curves downward into a pear-shaped chamber large enough for a comfortable nursery. A week or ten days may be spent by a couple in making it. The chips by which this good workman is known are left on the nursery floor, for woodpeckers do not pamper their babies with fine grasses, feathers or fur cradle linings, as the chickadee and some other birds do. A well-regulated woodpecker's nest contains five glossy-white eggs. Sheltered from the rain, wind and sun, hidden from almost every enemy except the red squirrel, woodpecker babies lie secure in their dark, warm nursery, with no excitement except the visits of their parents with a fat grub. Then how quickly they scramble up the walls toward the light and dinner!

YELLOW-BELLIED SAPSUCKER

This woodpecker I am sorry to introduce to you as the black sheep of his family, with scarcely a friend to speak a good word for him. Murder is committed on his immensely useful relatives, who have the misfortune to look ever so little like him, simply because ignorant people's minds are firmly fixed in the belief that every woodpecker is a sapsucker, therefore a tree-killer, which only this miscreant is, and very rarely. The rest of the family who drill holes in a tree harmlessly, even beneficially, do so because they are probing for insects. The sapsucker alone drills rings or belts of holes for the sake of getting at the soft inner bark and drinking the sap that trickles from it. Mrs. Eckstorm, who has made a careful study of the woodpeckers in a charming little book that every child should read, tells of a certain sapsucker that came silently and early in the autumn mornings to feed on a favourite mountain ash tree near her dining-room window. In time this rascal killed the tree. " Early in the day he showed considerable activity," writes Mrs. Eckstorm, "flitting from limb to limb and sinking a few holes, three or four in a row, usually above the previous upper girdle of the limbs he selected to work upon. After he had tapped several limbs, he would sit patiently waiting for the sap to flow, lapping it up quickly when the drop was large enough. At first he would be nervous, taking alarm at noises and wheeling away on his broad wings till his fright was over, when he would steal quietly back to his sap-holes. When not alarmed, his only movement was from one row of holes to another, and he tended them with considerable regularity. As the day wore on he became less excitable, and clung cloddishly to his tree trunk with ever increasing torpidity, until finally he hung motionless as if intoxicated, tippling in sap, a dishevelled, smutty, silent bird, stupefied with drink, with none of that brilliancy of plumage and light-hearted gaiety which made him the noisiest and most conspicuous bird of our April woods." But it must be admitted that very rarely does the sapsucker girdle a tree with holes enough to sap away its life. He may have an orgie of intemperance once in awhile, but much should be forgiven a bird as dexterous as a flycatcher in taking insects on the wing and with a hearty appetite for pests. Wild fruit and soft-shelled nuts he likes too. He never bores a tree to get insects as his cousins do, for only when a nest must be chiselled out is he a wood pecker in the strict sense. You may know this erring one by the pale, sulphur-yellow tinge on his white under parts, the white patch above the tail on his mottled black and white back, his spotted wings with conspicuous white coverts, the broad black patch on his breast extending to the corners of his mouth in a chin strap, and the lines of crimson on forehead, crown, chin and throat. He is smaller than a robin by two inches, yet larger than the English sparrow, who shares with him a vast amount of public condemnation.

RED-HEADED WOODPECKER

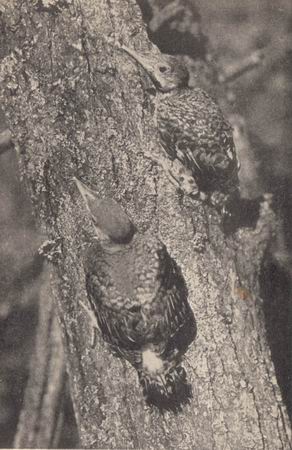

A pair of red-headed woodpeckers I know, who made their home in an old tree next the station yard at Atlanta, where locomotives clanged, puffed, whistled and shrieked all day long, evidently enjoyed the noise, for the male liked nothing better than to add to it by tapping on one of the glass non-conductors around which a telegraph wire ran. When first I saw the handsome, tri-coloured fellow he was almost enveloped in a cloud of smoke escaping from a puffing locomotive on the track next the telegraph pole, yet he tapped away unconcerned and as merrily as you would play a two-step on the piano. When the vapour blew away, his glossy bluish black and white feathers, laid on in big patches, were almost as conspicuous as his redhead, throat and upper breast. His mate is red-headed, too. All the woodpeckers have musical tastes. A flicker comes to my verandah to tap a galvanised rain gutter, for no other reason than the excellent one that he enjoys the sound. Tin-roofs everywhere are popular tapping places. Certain dry, dead, seasoned limbs of hardwood trees resound better than others and a woodpecker in love is sure to find out the best one in the spring when he beats a rolling tattoo in the hope of charming his best beloved. He has no need to sing, which is why he doesn't. Fence posts are the red-head's favourite resting places. From these he will make sudden sallies in mid-air, like a fly-catcher, after a passing insect; then return to his post. You remember that the blue jay has the thrifty habit of storing nuts for the proverbial rainy day, and that the shrike hangs up his meat to cure on a thorn tree like a butcher. Red-headed woodpeckers, who are especially fond of beechnuts, acorns and grasshoppers, hide them away, squirrel fashion, in tree cavities, in fence holes, crevices in old barns, between shingles on the roof, behind bulging boards, in the ends of railroad ties, in all sorts of queer places, to feast upon them in winter when the land is lean. Who knows whether other woodpeckers have hoarding places? The sapsucker, the hairy and the downy woodpeckers also like beechnuts; the flicker prefers acorns; but do they store them for winter use? The red-head's thrifty habit was only recently discovered: has it been only recently acquired? It must be simpler to store the summer's surplus than to travel to a land of plenty when winter comes. Heretofore this red-headed cousin has been reckoned a migratory member of the home-loving woodpecker clan, but only where he could not find plenty of beechnuts to keep him through the winter.  The sapsucker  Baby flickers just out of their hole FLICKER Called also: High-hole; Clape; Golden-winged Woodpecker; Yellow-hammer; Yucker Why should the flicker discard family traditions and wear clothes so different from those of his relations? His upper parts are dusty brown, narrowly barred with black, and the large white patch on his lower back, so conspicuous as he flies from you, is one of the best marks of identification on his big handsome body. His head is gray with a black streak below the eye, and a scarlet band across the nape of the neck, while the upper side of the wing feathers is black relieved by golden shafts. Underneath, the wings are a lovely golden yellow, seen only when the bird flies toward you. His breast, which is a pale, pinkish brown, is divided from the throat by a black crescent, smaller than the meadowlark's, and below this half-moon of jet there are many black spots. He is quite a little larger than a robin, the largest and the commonest of our five non-union carpenters. See him feeding on the ground instead of on the striped and mottled tree trunks, where his black and white striped relatives are usually found, and you will realise that he wears brown clothes, finely barred, because they harmonise so perfectly with the brown earth. What does he find on the ground that keeps him there so much of the time? Look at the spot he has just flown from and you will doubtless find ants. These are chiefly his diet. Three thousand of them, for a single meal, he has been known to lick out of a hill with his long, round, extensile, sticky tongue. Evidently this lusty fellow needs no tonic. His tail, which is less rounded than his cousins', proves that he has little need to prop himself against tree trunks to pick out a dinner; and his curved bill, which is more of a pickaxe than a hammer, drill, or chisel, is little used as a carpenter's tool except when a nest is to be dug out of soft, decayed wood. Although he can beat a rolling tattoo in the spring, he has a variety of call notes for use the year through. Did you ever see the funny fellow spread his tail and dance when he goes courting? Flickers condescend to use old holes deserted by their relatives who possess better tools. You must have noticed all through these bird biographies that the structure and colouring of every bird are adapted to its kind of life, each member of the same family varying according to its habits. The kind of food a bird eats and its method of getting it, of course, bring about most, if not all, of the variations from the family type. Each is fitted for its own life, "even as you and I." Like your pet pigeon, the hummingbird, and several other birds, parent flickers pump partly digested food from their own stomachs into those of their hungry babies. Imagine how many trips would have to be taken to a nest if ants were carried there one by one! How can the birds be sure they will not thrust their bills through the eyes of their blind, naked and helpless babies in so dark a hole? It must be very difficult to find the mouths and be sure none is neglected. Like the little pig you all know about, I suspect there is always at least one little flicker in the dark tree-hollow that "gets none" each trip. |