|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Birds Every Child Should Know Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Birds Every Child Should Know Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER II

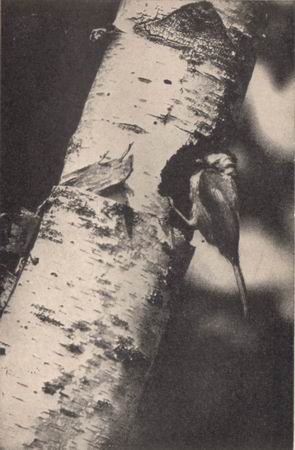

SOME NEIGHBOURLY ACROBATS CHICKADEE TUFTED TITMOUSE WHITE-BREASTED NUTHATCH RED-BREASTED NUTHATCH RUBY-CROWNED KINGLET GOLDEN-CROWNED KINGLET THE CHICKADEE Called also: Black-capped Titmouse BITTERLY cold and dreary though the day may be, that "little scrap of valour," the chickadee, keeps his spirits high until ours cannot but be cheered by the oft-repeated, clear, tinkling silvery notes that spell his name. Chicka-dee-dee: chicka-dee-dee: he introduces himself. How easy it would be for every child to know the birds if all would but sing out their names so clearly! Oh, don't you wish they would? "Piped a tiny voice near by Gay and polite -- a cheerful cry Chick-chicka-dee-dee! Saucy note Out of sound heart and merry throat, As if it said, `Good day, good Sir! Fine afternoon, old passenger! Happy to meet you in these places where January brings few faces."' No bird, except the wren, is more cheerful than the chickadee, and his cheerfulness, fortunately, is just as "catching" as measels. None will respond more promptly to your whistle in imitation of his three very high, clear call notes, and come nearer and nearer to make quite sure you are only a harmless mimic. He is very inquisitive. Although not a bird may be in sight when you first whistle his call, nine chances out of ten there will be a faint echo from some far distant throat before very long; and by repeating the notes at short intervals you will have, probably, not one but several echoes from as many different chickadees whose curiosity to see you soon gets the better of their appetites and brings them flying, by easy stages, to the tree above your head. Where there is one chickadee there are apt to be more in the neighbourhood; for these sociable, active, cheerful little black-capped fellows in gray like to hunt for their living in loose scattered flocks throughout the fall and winter. When they come near enough, notice the pale rusty wash on the sides of their under parts which are more truly dirty white than gray. Chickadees are wonderfully tame: except the chipping sparrow, perhaps the tamest birds that we have. Patient people, who know how to whistle up these friendly sprites, can sometimes draw them close enough to touch, and an elect few, who have the special gift of winning a wild bird's confidence, can induce the chickadee to alight upon their hands. Blessed with a thick coat of fat under his soft, fluffy gray feathers, a hardy constitution and a sunny disposition, what terrors has the winter for him? When the thermometer goes down, his spirits seem to go up the higher. Dangling like a circus acrobat on the cone of some tall pine tree; standing on an outstretched twig, then turning over and hanging with his black-capped head downward from the high trapeze; carefully inspecting the rough bark on the twigs for a fat grub or a nest of insect eggs, he is constantly hunting for food and singing grace between bites. His day, day, day, sung softly over and over again, seems to be his equivalent for "Give us this day our daily bread." How delightfully he and his busy friends, who are always within call, punctuate the snowmuffled, mid-winter silence with their ringing calls of good cheer! The orchards where chickadees, titmice, nuthatches, and kinglets have dined all winter, will contain few worm-eaten apples next season. Here is a puzzle for your arithmetic class: If one chickadee eats four hundred and forty-four eggs of the apple tree moth on Monday, three hundred and thirty-three eggs of the canker worm on Tuesday, and seven hundred and seventy-seven miscellaneous grubs, larvae, and insect eggs on Wednesday and Thursday, how long will it take a flock of twenty-two chickadees to rid an orchard of every unspeakable pest? One very wise and thrifty fruit grower I know attracts to his trees all the winter birds from far and near, by keeping on several shelves nailed up in his orchard, bits of suet, cheap raisins, raw peanuts-chopped fine, cracked hickory nuts and rinds of pork. The free lunch counters are freely patronised. There is scarcely an hour in the day, no matter how cold, when some hungry feathered neighbour may not be seen helping himself to the heating, fattening food he needs to keep his blood warm. At the approach of warm weather, chickadees retreat from public gaze to become temporary recluses in damp, deep woods or woodland swamps where insects are most plentiful. For a few months they give up their friendly flocking ways and live in pairs. Long journeys they do not undertake from the North when it is time to nest; but Southern birds move northward in the spring. Happily the chickadee may find a woodpecker's vacant hole in some hollow tree; worse luck if a new excavation must be made in a decayed birch-the favourite nursery. Wool from the sheep pasture, felt from fern fronds, bits of bark, moss, hair, and the fur of "little beasts of field and wood" -- anything soft that may be picked up goes to line the hollow cradle in the tree-trunk. How the crowded chickadee babies must swelter in their bed of fur and feathers tucked inside a close, stuffy hole! Is it not strange that such hardy parents should coddle their children so?  The chickadee at her front door

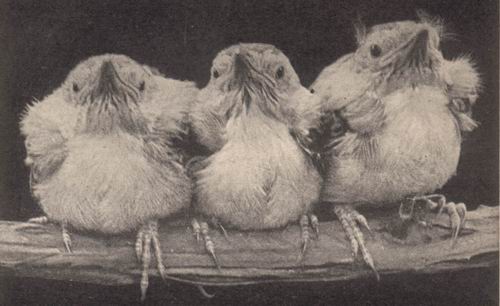

Young nuthatches learning their first lesson in balancing on a horizontal bar.

TUFTED TITMOUSE

Called also: Peto Bird; Crested Tomtit; Crested Titmouse Don't expect to meet the tufted titmouse if you live very far north of Washington. He is common only in the South and West. This pert and lively cousin of the lovable little chickadee is not quite so friendly and far more noisy. Peto-peto-peto comes his loud, clear whistle from the woods and clearings where he and his large family are roving restlessly about all through the autumn and winter. A famous musician became insane because he heard one note ringing constantly in his overwrought brain. If you ever hear a troupe of titmice whistling Peto over and over again for hours at a time, you will pity poor Schumann and fear a similar fate for the birds. But they seem to delight in the two tiresome notes, uttered sometimes in one key, sometimes in another. Another call -- day-day-day -- reminds you of the chickadee's, only the tufted titmouse's voice is louder and a little hoarse, as it well might be from such constant use. Few birds that we see about our homes wear a top knot on their heads. The big cardinal has a handsome red one, the larger blue jay's is bluish gray, the cedar waxwing's is a Quaker drab; but the little titmouse, who is the size of an English sparrow, may be named at once by the gray pointed crest that makes him look so pert and jaunty. When he hangs head downward from the trapeze on the oak tree, this little gray acrobat's peaked cap seems to be falling off; whereas the black skull cap on the smaller chickadee fits close to his head no matter how much he turns over the bar and dangles. Neither one of these cousins is a carpenter like the woodpecker. The titmouse has a short, stout bill without a chisel on it, which is why it cannot chip out a hole for a nest in a tree trunk or old stump unless the wood is much decayed. You see why these birds are so pleased to find a deserted woodpecker's hole. Not alone are they saved the trouble of making one, but a deep tunnel in a tree-trunk means security for their babies against hawks, crows, jays, and other foes, as well as against wind and rain. When you find a flock of either chickadees or titmice, you may be sure it is made up chiefly, if not entirely, of the birds of one or two broods of the same parents. Their families are usually large and the members devoted to one another. Titmice nest in April so that you cannot tell the brothers and sisters from the father and mother when the troupe of acrobats leave the woods in early autumn and whistle lustily about your home.

WHITE-BREASTED NUTHATCH

Called also: Tree Mouse; Devil Downhead When it comes to acrobatic performances in the trees, neither the chickadee nor the titmouse can rival their relatives, the little bluish gray nuthatches. Indeed, any circus might be glad to secure their expert services. Hanging fearlessly from the topmost branches of the tallest pine, running along the under side of horizontal limbs as comfortably as along the top of them, or descending the trunk head foremost, these wonderful little gymnasts keep their nerves as cool as the thermometer in January. From the way they travel over any part of the tree they wish, from top and tip to the bottom of it, no wonder they are sometimes called Tree Mice. Only the fly that walks across the ceiling, however, can compete with them in clinging to the under side of boughs. Why don't they fall off? If you ever have a chance, examine their claws. These, you will see, are very much curved and have sharp little hooks that catch in any crack or rough place in the bark and easily support the bird's weight. As a general rule the chickadee keeps to the end of the twigs and the smaller branches; the tufted titmouse rids the larger boughs of insects, eggs, and worms hidden in the scaly bark; but the nuthatches can climb to more inaccessible places. With the help of the hooks on their toes it does not matter to them whether they run upward, downward, or sidewise; and they can stretch their bodies away from their feet at some very queer angles. Their long bills penetrate into deep holes in the thick bark of the tree trunks and older limbs and bring forth from their hiding places insects that would escape almost every other bird except the brown creeper and the woodpecker. Of course, when you see any feathered acrobat performing in the trees, you know he is working hard to pick up a dinner, not exercising merely for fun. The most familiar nuthatch, in the eastern United States, is the one with the white breast; but in the Northern States and Canada there is another common winter neighbour, a smaller compactly feathered, bluish gray gymnast with a pale rusty breast, a conspicuous black line running apparently through his eye from the base of his bill to the nape of his neck, and heavy white eyebrows. This is the hardy little red-breasted nuthatch. His voice is pitched rather high and his drawling notes seem to come from a lazy bird instead of one of the most vigorous and spry little creatures in the wood. The nasal ank-ank of his white-breasted cousin is uttered, too, without expression, as if the bird were compelled to make a sound once in a while against his will. Both of these cousins have similar habits. Both are a trifle smaller than the English sparrow. In summer they merely hide away in the woods to nest, for they are not migrants. It is only when nesting duties are over in the autumn that they become neighbourly. Who gave them their queer name? A hatchet would be a rather clumsy tool for us to use in opening a nut, but these birds have a convenient, ever-ready one in their long, stout, sharply pointed bills with which they hack apart the small thin-shelled nuts like beech nuts and hazel nuts, chinquapins and chestnuts, kernels of corn and sunflower seeds. These they wedge into cracks in the bark just big enough to hold them. During the summer and early autumn when insects are plentiful, the nuthatches eat little else; and then they thriftily store away the other items on their bill of fare, squirrel fashion, so that when frost kills the insects, they may vary their diet of insect eggs and grubs with nuts and the larger grain. Flying to the spot where a nut has been securely wedged, perhaps weeks before, the bird scores and hacks and pecks it open with his sharp little hatchet, whose hard blows may be heard far away. Although this tool is a great help to the nuthatches in making their nests, they appear to be quite as ready to accept a deserted woodpecker's hole as the chickadee with a smaller bill. A natural cavity will answer, or, if they must, they will make one in some forest tree. The red-breasted nuthatches have a curious habit of smearing the entrance to the hole with fir-balsam or pitch. Why do you suppose they do it? Perhaps they think this will discourage egg suckers, like snakes, mice, or squirrels; but, in effect, the sticky gum often pulls the feathers from their own breasts as they go in and out attending to the wants of their family.

RUBY-CROWNED KINGLET

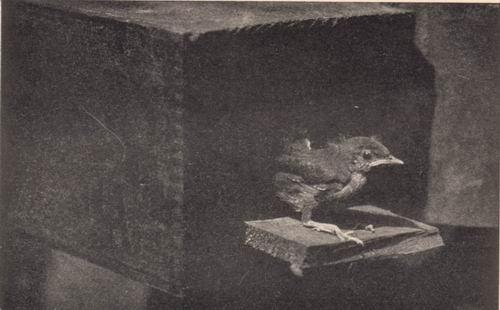

Count that a red-letter day on your calendar when first you see either this tiny, dainty sprite, or his next of kin, the golden-crowned kinglet, fluttering, twinkling about the evergreens. In republican America we don't often have the chance to meet two crowned heads. Energetic as wrens, restless as warblers, and as perpetually looking for insect food, the kinglets flit with a sudden, jerking motion from twig to twig among the trees and bushes, now on the lawn, now in the orchard and presently in the hedgerow down the lane. They have a pretty trick of lifting and flitting their wings every little while. The bluebird and pine grosbeak have it too, but their much larger, trembling wings seem far less nervous. Happily the kinglets are not at all shy; no bird is that is hatched out so far north that it never sees a human being until it travels southward to spend the winter. Alas! It is the birds that know us too well that are often the most afraid. When the leaves are turning crimson and russet and gold in the autumn, keep a sharp look out for the plump little grayish, olive green birds that are even smaller than wrens, and not very much larger than hummingbirds. Although members of quite a different family -- the kinglets are exclusive-they condescend to join the nuthatches and chickadees in the orchard to help clean the farmer's fruit trees or pick up a morsel at the free lunch counter in zero weather. Love or war is necessary to make the king show us his crown. But vanity or anger is sufficient excuse for lifting the dark feathers that nearly conceal the beauty spot on the top of his head when the midget's mind is at ease. If you approach very near -- and he will allow you to almost touch him -- you may see the little patch of brilliant red feathers, it is true, but you will probably get an unexpected, chattering scolding from the little king as he flies away. In the spring his love song is as surprisingly strong in proportion to his size as the wren's. It seems impossible for such a volume of mellow flute-like melody to pour from a throat so tiny. Before we have a chance to hear it again the singer is off with his tiny queen to nest in some spruce tree beyond the Canadian border.  The noisy contents of a soap box: a family of house wrens.  The marsh wren's round cradle swung among the rushes |