| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

XXIV In which I discover many strange things in that strange land, America; visit San Francisco for the first time; and meet an astounding reception in the offices of a cinematograph company. Now, since I was twenty at the time, four years ago, when I stood on the deck of the steamer and saw America rising into view on the horizon, it may seem strange to some persons that I had no truer idea of this country than to suppose just west of New York a wild country inhabited by American Indians and traversed by great herds of buffalo. It is natural enough, however, when one reflects that I had spent nearly all my life in London, which is, like all great cities, a most narrow-minded and provincial place, and that my only schooling had been the little my mother was able to give me, combined later with much eager reading of romances, Fenimore Cooper, your own American writer, had pictured for me this country as it was a hundred years ago, and what English boy would suppose a whole continent could be made over in a short hundred years? So, while the steamer docked, I stood quivering with eagerness to be off into the wonders of that forest of skyscrapers which is New York, with all the sensations of a boy transported to Mars, or any other unknown world, where anything might happen. Indeed, one of the strangest things — to my way of thinking — which I encountered in the New World, was brought to my attention a moment after I landed. At the very foot of the gangplank Mr. Reeves, the manager of the American company, who was with me, was halted by a very fat little man, richly dressed, who rushed up and grasped him enthusiastically by both hands. "Velgome! Velgome to our gountry!" he cried. "How are you, Reeves? How goes it?" Mr. Reeves replied in a friendly manner, and the little man turned to me inquiringly. "Who's the kid?" he asked. "This is Mr. Chaplin, our leading comedian," Mr. Reeves said, while I bristled at the word "kid." The fat man, I found, was Marcus Loew, a New York theatrical producer. He shook hands with me warmly and asked immediately, "Vell, and vot do you think of our gountry, young man?" "I have never been in Berlin," I said stiffly. "I have never cared to go there," I added rudely, resenting his second reference to my youth. "I mean America. How do you like America? This is our gountry now. We're all Americans together over here!" Marcus Loew said with real enthusiasm in his voice, and I drew myself up in haughty surprise. "My word, this is a strange country," I said to myself. Foreigners, and all that, calling themselves citizens! This is going rather far, even for a republic, even for America, where anything might happen. That was the thing which most impressed me for weeks. Germans, it seemed, and English and Irish and French and Italians and Poles, all mixed up together, all one nation — it seemed incredible to me, like something against all the laws of nature. I went about in a continual wonder at it. Not even the high buildings, higher even than I had imagined, nor, the enormous, flaming electric signs on Broadway, nor the high, hysterical, shrill sound of the street traffic, so different from the heavy roar of London, was so strange to me as this mixing of races. Indeed, it was months before I could become accustomed to it, and months more before I saw how good it is, and felt glad to be part of such a nation myself. We were playing a sketch called A Night in a London Music-Hall, which probably many people still remember. I was cast for the part of a drunken man, who furnished most of the comedy, and the sketch proved to be a great success, so that I played that one part continuously for over two years, traveling from coast to coast with it twice. The number of American cities seemed endless to me, like the little boxes the Chinese make, one inside the other, so that it seems no matter how many you take out, there are still more inside. I had imagined this country a broad wild continent, dotted sparsely with great cities — New York, Chicago, San Francisco — with wide distances between. The distances were there, as I expected, but there seemed no end to the cities. New York, Buffalo, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Columbus, Indianapolis, Chicago, St. Louis, Kansas City, Omaha, Denver — and San Francisco not even in sight yet! No Indians, either. Toward the end of the summer we reached San Francisco the first time, very late, because the train had lost time over the mountains, so that there was barely time for us to reach the Orpheum and make up in time for the first performance. My stage hat was missing, there was a wild search for it, while we held the curtain and the house grew a little impatient, but we could not find it anywhere. At last I seized a high silk hat from the outraged head of a man who had come behind the scenes to see Reeves and rushed on to the stage. The hat was too loose. Every time I tried to speak a line it fell off, and the audience went into ecstasies. It was one of the best hits of the season, that hat. It slid back down my neck, and the audience laughed; it fell over my nose, and they howled; I picked it up on the end of my cane, looked at it stupidly and tried to put the cane on my head, and they roared. I do not know the feelings of its owner, who for a time stood glaring at me from the wings, for when at last, after the third curtain call, I came, off holding the much dilapidated hat in my hands, he had gone. Bareheaded, I suppose, and probably still very angry. After the show I came out on the street into a cold gray fog, which blurred the lights and muffled the sound of my steps on the damp pavement, and, drawing great breaths of it into my lungs, I was happy. "For the lova Mike!" I said to Reeves, being very proud of my American slang. "This is a little bit of all right, what? Just like home, don't you know! What do you know about that!" And I felt that, next to London, I liked San Francisco, and was sorry we were to stay only two weeks. We returned to New York, playing return dates on the "big time" circuits, and I almost regretted the close of the season and the return to London. The night we closed at Keith's I found a message waiting for me at the theater. "We want you in the pictures. Come and see me and talk it over. Mack Sennett." "Who's Mack Sennett?" I asked Reeves, and he told me he was with the Keystone motion-picture company. "Oh, the cinematographs!" I said, for I knew them in London, and regarded them as even lower than the music-halls. I tore up the note and threw it away. "I suppose we're going home next week?" I asked Reeves, and he said he thought not; the "little big time" circuits wanted us and he was waiting for a cable from Carno. Early next day I called at his apartments, eager to learn what he had heard, for I wanted very much to stay in America another year, and saw no way to do it if Carno recalled the company. I did not think again of the note from Sennett, for I did not regard seriously an offer to go into the cinematographs. I was delighted to hear that we were going to stay, and left New York in great spirits, with the prospect of another year with A Night in a London Music-Hall in America. Twelve months later, back in New York again, I received another message from Mr. Sennett, to which I paid no more attention than to the first one. We were sailing for London the following month. One day, while I was walking down Broadway with a chance acquaintance, we passed the Keystone offices and my companion asked me to come in with him. He had some business with a man there. I went in, and was waiting in the outer office when Mr. Sennett came through and recognized me. "Good morning, Mr. Chaplin, glad to see you! Come right in," he said cordially, and, ashamed to tell him I had not come in reply to his message, that indeed I had not meant to answer it at all, I followed him into his private office. I talked vaguely, waiting for an opportunity to get away without appearing rude. At last I saw it. "Let's not beat about the bush any longer," Mr. Sennett said. "What salary will you take to come with the Keystone?" This was my chance to end the interview, and I grasped it eagerly. "Two hundred dollars a week," I said, naming the most extravagant price which came into my head. "All right," he replied promptly. "When can you start?

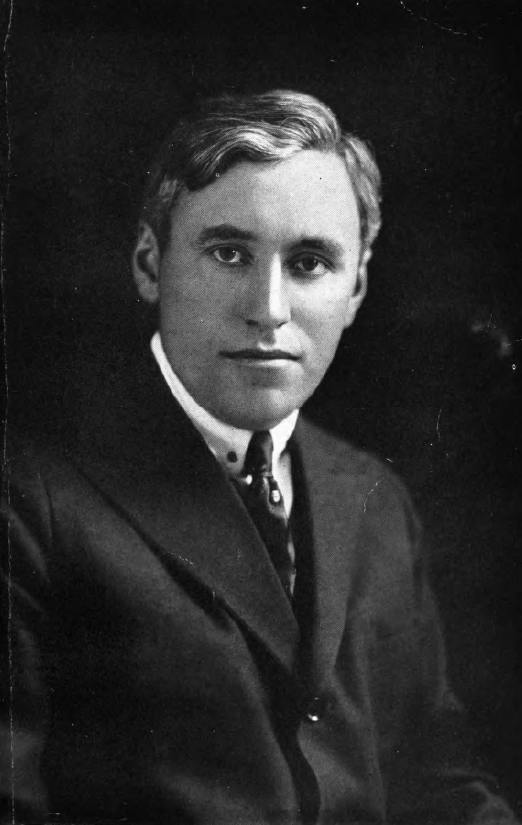

Mack Sennett |