| Web and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2016 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER XII. Captain Sharp and his company depart from the Isle of Plate, in prosecution of their voyage towards Arica. They take two Spanish vessels by the way, and learn intelligence from the enemy. Eight of their company destroyed at the Isle of Gallo. Tediousness of this voyage, and great hardships they endured. Description of the coast all along, and their sailings.

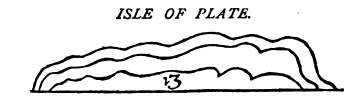

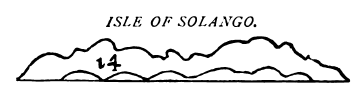

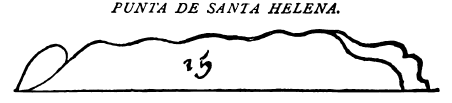

HAVING taken in at the Isle of Plate what provisions and other necessaries we could get, we set sail thence on Tuesday, August 17th, 1679, in prosecution of our voyage and designs above-mentioned, to take and plunder the vastly rich town of Arica. This day we sailed so well, and the same we did for several others afterwards, that we were forced to lie by several times, besides reefing our topsails, to keep our other ship company. lest we should lose her again. The next morning about break of day, we found ourselves to be at the distance of seven or eight leagues to the westward of the island whence we had departed, standing W. by S. with a S. by W. wind. About noon that day we had laid the land. After dinner the wind came at S.S.W. at which time we were forced to stay more than once for the other vessel belonging to our company. On the following day we continued in like manner a west course all the day long. Sometimes this day the wind would change, but then in a quarter of an hour it would return to S.S.W. again. Hereabouts where we now were, we observed great ripplings of the sea. August 20th, yesterday in the afternoon about six o'clock, we stood in S.E., but all night and all this day, we had very small winds. We found still that we gained very much on the small ship, which did not a little both perplex and hinder us in our course. The next day likewise we stood in S.E. by S. though with very little wind, which sometimes varied, as was mentioned above. That day I finished two quadrants, each of which were two feet and a half radius. Here we had in like manner, as has been mentioned on other days of our sailings, very many dolphins, and other sorts of fish swimming about our ship. On the morning following, we saw again the island of Plate at N.E. of our ship, giving us this appearance at that distance of prospect:  The same day at the distance of six leagues more or less from the said island, we saw another island, called Solango. This isle lies close in by the mainland. In the evening we observed it to bear E.N.E. from us. Our course was S.E. by S. and the wind at S.W. by S. This day likewise we found that our lesser ship was still a great hindrance to our sailing, being forced to lie by, and stay for her two or three hours every day. We found likewise, that the farther from shore we were, the less wind we had all along, and that under the shore we were always sure of a .fresh gale, though not so favourable to us as we could wish it to be. Hitherto we had used to stand off forty leagues, and yet notwithstanding, in the space of six days, we had not got above ten leagues on our voyage, from the place of our departure. August 23rd, this day the wind was S.W. by S. and S.S.W. In the morning we stood off.. The island of Solango, at N.E. by N. appears thus:  At S. by W. and about six leagues distance from us, we descried a long and even hill. I took it to be an island, and conjectured it might be at least eight leagues distant from the continent. But afterwards we found it was a point of land joining to the main, and is called Point St. Helena, being continued by a piece of land which lies low, and in several places is almost drowned from sight, so that it cannot be seen at two leagues distance. In this lowland the Spaniards have conveniences for making pitch, tar, salt, and some other things, for which purpose they have several houses here, and a friar, who serves them as their chaplain. From the island of Solango, to this place, are reckoned eleven leagues, more or less. The land is hereabouts indifferent high, and is likewise full of bays. We had this day very little wind to help us in our voyage, excepting what blasts came now and then in snatches. These sometimes would prove pretty fair to us, and allow us for some little while a south course. But our chief course was S.E. by S. The point of St. Helena at S. half E., and at about six leagues distance, gives exactly this appearance as follows

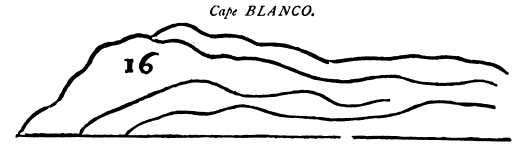

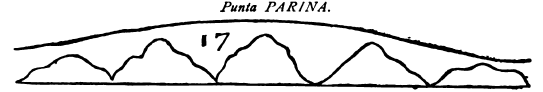

Here we found no great current of the sea to move anyway. At the isle of Plata, afore described, the sea ebbs and flows nearly thirteen feet perpendicular. About four leagues to leeward of this point is a deep bay, having a key at the mouth of it, which takes up the better part of its width. In the deepest part of the bay on shore, we saw a great smoke, which was at a village belonging to the bay, to which place the people were removed from the point above-mentioned. This afternoon we had a small westerly wind, our course being S.S.W. Hereabouts it is all along a very bold shore. At three o'clock in the afternoon, we tacked about to clear the point. Being now a little way without the point, we spied a sail, which we conceived to be a bark. Hereupon we hoisted out our canoe, and sent in pursuit of her, which made directly for the shore. But the sail proved to be nothing else than a pair of bark-logs,1 which arriving on shore, the men spread their sail on the sand of the bay to dry. At the same time there came down on the shore an Indian on horseback, who hallooed to our canoe, which had followed the logs. But our men fearing to discover who we were, in case they went too near the shore, left the design and returned back to us. In these parts the Indians have no canoes, nor any wood indeed that may be thought fit to make them of. Had we been descried by these poor people, they would in all probability have been very fearful of us. But they offered not to stir, which gave us to understand they knew us not. We could perceive from the ship a great path leading to the hills, so that we believed this place to be a look-out, or watch-place, for the security of Guayaquil. Between four and five we doubled the point, and then we descried the Point Chandy, at the distance of six leagues S.S.E. from this point. At first sight it seemed like to a long island, but withal, lower than that of St. Helena. Tuesday, August 24th, at noon we took the other ship, wherein Captain Cox sailed in tow, she being every day a greater hindrance than before to our voyage. Thus, about three in the afternoon we lost sight of land, in standing over for Cape Blanco. Here we found a strong current to move to the S.W. The wind was at S.W. by S., our course being S. by E. At the upper end of this gulf, which is framed by the two capes aforementioned, stands the city of Guayaquil, being a very rich place, and the embarcadero or sea-port to the great city of Quito. To this place likewise, many of the merchants of Lima do usually send the money they design for Old Spain in barks, and by that means save the custom that otherwise they would pay to the king by carrying it on board the fleet. Hither comes much gold from Quito, and very good and strong broadcloth, together with images for the use of the churches, and several other things of considerable value. But more especially cacao-nut, whereof chocolate is made, which is supposed here to be the best in the whole universe. The town of Guayaquil consists of about one hundred and fifty great houses, and twice as many little ones. This was the town to which Captain Sawkins intended to make his voyage, as was mentioned above. When ships of greater burden come into this gulf, they anchor outside Lapina, and then put their lading into lesser vessels to carry it to the town. Towards the evening of this day, a small breeze sprang up, varying from point to point, after which, about nine o'clock at night, we tacked about, and stood off to sea, W. by N. As soon as we had tacked, we happened to spy a sail N.N.E. from us. Hereupon we instantly cast off our other vessel which we had in tow, and stood round about after them. We came very near to the vessel before the people saw us, by reason of the darkness of the night. As soon as they spied us, they immediately clapped on a wind, and sailed very well before us; insomuch, that it was a pretty while before we could come up with them, and within call. We hailed them in Spanish, by means of an Indian prisoner, and commanded them to lower their top-sails. They answered they would soon make us to lower our own. Hereupon, we fired several guns at them, and they as thick at us again with their Harquebuses. Thus they fought us for the space of half an hour or more, and would have done it longer, had we not killed the man at the helm, after which, none of the rest dared to be so hardy as to take his place. With another of our shot we cut in pieces and disabled their main-top halliards. Hereupon they cried out for quarter, which we gave them, and entered their ship. Being possessed of the vessel, we found in her five and thirty men, of which number twenty-four were natives of Old Spain. They had one and thirty fire-arms on board the ship, for their defence. They had only fought us, as they declared afterwards, out of bravado, having promised on shore so to do, in case they met us at sea. The captain of this vessel was a person of quality, and his brother, since the death of Don Jacinto de Barabona, killed by us in the engagement before Panama, was„now made admiral of the sea armada. With him we took also in this bark, five or six other persons of quality. They did us in this fight, though short, very reat damage in our rigging, by cutting it in pieces, besides which, they wounded two of our men, and a third man was wounded by the negligence of one of our own men, occasioned by a pistol which went off unadvisedly. About eleven o'clock this night we stood off to the west. The next morning about break of day, we hoisted out our canoe, and went aboard the bark which we had taken the night before. We transported on board our own ship more of the prisoners taken in the said vessel, and began to examine them, to learn what intelligence we could from them. The captain of the vessel, who was a very civil and meek gentleman, satisfied our desires in this point very exactly, saying to us: Gentlemen, I am now your prisoner at wal by the over-ruling providence of fortune; and moreover, am very well satisfied that no money whatsoever can procure my ransom, at least for the present at your hands. Hence I am persuaded, it is not my interest to tell you a lie, which if I do, I desire you to punish me as severely as you shall think fit. We heard of your taking and destroying our Armadillo, and other ships at Panama, about six weeks after that engagement, by two several barks which arrived here from thence. But they could not inform us whether you designed to come any farther to the southward; but rather, desired we would send them speedily all the help by sea that we could. Hereupon, we sent the noise and rumour of your being in these seas, by land to Lima, desiring they would expedite what succours they could send to join with ours. We had at that time in our harbour two or three great ships, but all of them very unfit to sail. For this reason at Lima, the Viceroy of Peru pressed three great merchant ships, into the biggest of which he put fourteen brass guns, into the second, ten, and in the other, six. To these he added two barks, and put seven hundred and fifty soldiers on board them all. Of this number of men they landed eight-score at Point St. Helena; all the rest being carried down to Panama, with design to fight you there. Besides these forces, two other men of war, bigger than the afore-mentioned, are still lying at Lima, and fittin;. out there in all speed to follow and pursue you. One of these men of war is equipped with thirty-six brass guns, and the other with thirty. These ships, beside their complement of seamen, have four hundred soldiers added to them by the Viceroy. Another man of war belonging to this number, and lesser than the afore-mentioned, is called the Patache. This ship consists of twenty-four guns, and was sent to Arica to fetch the King's plate thence. But the Viceroy, having received intelligence of your exploits at Panama, sent for this ship back from thence with such haste, that they came away and left the money behind them. Hence the Patache now lies at the Port of Callao, ready to sail on the first occasion, or news of your arrival thereabouts, they having for this purpose sent to all parts very strict orders to keep a good look-out on all sides, and all places along the coasts. Since this, from Manta, they sent us word that they had seen two ships at sea pass by that place. And from the Goat Key also we heard that the Indians had seen you, and that they were assured, one of your vessels was the ship called la Trinidad, which you had taken before Panama, as being a ship very well known in these seas. Hence we concluded that your design was to ply, and make your voyage thereabouts. Now this bark, wherein you took us prisoners, being bound for Panama, the Governor of Guayaquil sent us out before her departure, if possible, to discover you, which if we did, we were to run the bark on shore and get away, or else to fight you with these soldiers and firearms that you see. As soon as we heard of your being in these seas, we built two forts, the one of six guns, and the other of four, for the defence of the town. At the last muster taken in the town of Guayaquil we had there eight hundred and fifty men, of all colours; but when we came out, we left only two hundred men that were actually under arms. Thus ended the relation of that worthy gentleman. About noon that day we unrigged the bark which we had taken, and after so doing sunk her. Then we stood S.S.E.; and afterwards S. by W. and S. S. W. That evening we saw point St. Helena at N. half E., at the distance of nine leagues, more or less. The next day, being August 26th, in the morning we stood S. That day we cried out all cur pillage, and found that it amounted to 3,276 pieces of eight, which was accordingly divided by shares amongst us. We also punished a friar, who was chaplain to the bark afore-mentioned, and shot him upon the deck, casting him overboard before he was dead. Such cruelties, though I abhorred very much in my heart, yet here was I forced to hold my tongue and contradict them not, as having not authority to oversway them. At ten o'clock this morning we saw land again, and the pilot said we were sixteen leagues to leeward of Cabo Blanco. Hereupon we stood off, and on, close under the shore, which all appeared to be barren land. The morning following we had very little wind, so that we advanced but slowly all that day. To windward of us we could perceive the continent to be all high land, being whitish clay, full of white cliffs. This morning, in common discourse, our prisoners confessed to us, and acknowledged the destruction of one of our little barks, which we lost on our way to the Island of Cayboa. They stood away, as it appeared by their information, for the Goat Key, thinking to find us there, as having heard Captain Sawkins say that he would go thither. On their way they happened to fall in with the island of Gallo, and understanding its weakness by their Indian pilot, they ventured on shore, and took the place, carrying away three white women in their company. But after a small time of cruising, they returned again to the aforesaid island, where they stayed two or three days, after which they went out to sea again. Within three or four days they came to a little key four leagues distant from this isle. But whilst they had been out and in thus several times, one of their prisoners made his escape to the mainland, and brought off thence fifty men with firearms. These, placing themselves in ambush, at the first volley killed six of the seven men that belonged to the bark. The other man that was left, took quarter of the enemy, and he it was that discovered to them our design upon the town of Guayaquil. By an observation which we made this day, we found ourselves to be in lat. 3° 50". At this time, our prisoners told us, there was an embargo laid on all the Spanish ships, commanding them not to stir out of the ports, for fear of their falling into our hands at sea. Saturday, August 28th. This morning we took out all the water, and most part of the flour that was in Captain Cox's vessel. The people in like manner came on board our ship. Having done this, we made a hole in the vessel, and left her to sink, with a small old canoe at her stern. To leeward of Manta, a league from shore, in eighteen fathom water, there runs a great current outwards. About eleven in the forenoon we weighed anchor, with a wind at W.N.W. turning it out. Our number now in all being reckoned, we found ourselves to be one hundred and forty men, two boys, and fifty-five prisoners, being all now in one and the same bottom. This day we got six or seven leagues in the wind's eye. All the day following we had a very strong S.S.W. wind, insomuch that we were forced to sail with two reefs in our main-top sail, and one also in our fore-top sail. Here Captain Peralta told us that the first place which the Spaniards settled in these parts, after Panama, was Tumbes, a place that now was to leeward of us, in this gulf where we now were. That there a priest went ashore with a cross in his hand, while ten thousand Indians stood gazing at him. Being landed on the strand, there came out of the woods two lions; and he laid the cross gently on their backs, and they instantly fell down and worshipped it: and moreover, that two tigers following them, did the same; whereby these animals gave to the Indians to understand the excellency of the Christian religion, which they soon after embraced. About four in the evening we came abreast the cape, which is the highest part of all. The land hereabouts appeared to be barren and rocky. At three leagues distance east from us, the cape showed thus:  Were it not for a windward current which runs under the shore hereabouts, it were totally impossible for any ships to get about this cape, there being such a great current to leeward in the offing. In the last bark which we took, of which we spoke in this chapter, we made prisoner one Nicolas Moreno, a Spaniard by nation, and who was esteemed to be a very good pilot of the South Sea. This man did not cease continually to praise our ship for her sailing, and especially for the alterations we had made in her. As we went along, we observed many bays to lie between this cape and Point Parina, of which we shall soon make mention hereafter. In the night the wind came about to S.S.E. and we had a very stiff gale of it. So that by break of day the next morning, we found ourselves to be about five leagues distant to windward of the cape afore mentioned. The land hereabouts makes three or four several bays, and grows lower and lower the nearer we came to Punta Parina. This point looks at first sight like two islands. Between four and five of the clock that evening we were W. from the said point. The next day likewise, being the last day of August, the wind still continued S.S.E. as it had done the whole day before. This day we thought it convenient to stand farther out to sea, for fear of being descried at Paita, which now was not very far distant from us. The morning proved to be hazy — but about eleven we spied a sail, which stood then just as we did E. by S. Coming nearer to it, by degrees we found her to be nothing else than a pair of bark logs2 under a sail, which were going that way. Our pilot advised us not to meddle with those logs, nor mind them in the least, for it was very doubtful whether we should be able to come up with them or not, and then by giving chase to them, we should easily be descried and known to be the English pirates, as they called us. These bark logs sail excellently well for the most part, and some of them are of such a size that they will carry two hundred and fifty packs of meal from the valleys to Panama, without wetting any of it. This day, by an observation made, we found ourselves to be in lat. 4° 55' S; point Parina at N.E. by E. and at the distance of six leagues, more or less, gives this following appearance:

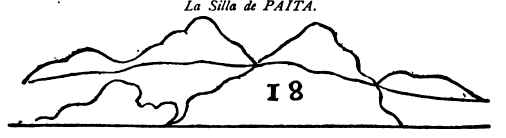

At the same time La Silla de Paita bore from us S.E. by E. being distant only seven or eight leagues. It had the form of a high mountain, and appeared thus to us:

The town of Paita itself is situated in a deep bay, about two leagues to leeward of this hill. It serves for an Embarcadero, or port town, to another great place which is distant thence about thirteen leagues higher in the country, and is called Piura, seated in a very barren country. On Wednesday, September 1st, our course was S. by W. The midnight before this day we had a landwind that sprang up. In the afternoon La Silla de Paita, at the distance of seven leagues, at E. by N. appeared thus:

All along hereabouts is nothing but barren land, as was said before; likewise, for three or four days last past, we observed along the coasts many seals. That night as we sailed we saw something that appeared to us to be as it were a light. And the next morning we spied a sail, whence we judged the light had come. The vessel was at the distance of six leagues from us, in the wind's eye, and thereupon we gave her chase. She stood to windward as we did. This day we had an observation, which gave us lat. 5° 30' S. At night we were about four leagues to leeward of her, but so great a mist fell, that we suddenly lost sight of her. At this time the weather was as cold with us as in England in November. Every time we went about with our ship the other did the like. Our pilot told us that this ship set forth from Guayaquil eleven days before they were taken, and that she was lader with rigging, woollen and cotton cloth, and other manufactures, made at Quito. Moreover, that he had heard that they had spent a mast and had put into Paita to refit it. The night following they showed us several lights through their negligence, which they ought not to have done, for by that means we steered directly after them. The next morning she was more than three leagues in the wind's eye distant from us. Had they suspected us, it could not be doubted, but they would have made away towards the land, but they seemed not to fly nor stir for our chase. The land here all along is level, and not very high. The weather was hazy, so that at about eleven o'clock that morning we lost sight of her. At this time we had been for the space of a whole week, at an allowance of only two draughts of water each day, so scarce were provisions with us. That afternoon we saw the vessel again, and at night we were not full two leagues distant from her, and not more than half a league to leeward. We made short trips all the night long. On Saturday, September 4th, about break of day, we saw the ship again, at the distance of a league, more or less, and not above a mile to windward of us. They stood out as soon as they espied us, and we stood directly after them. Having pursued them for several hours, about four of the clock in the afternoon, we came up within the distance of half our small arms shot, to windward of them. Hereupon they, perceiving who we were, presently lowered all their sails at once, and we cast dice among ourselves for the first entrance. The lot fell to larboard; so that twenty men belonging to that watch entered her. In the vessel were found fifty packs of cacao-nut, such as chocolate is made of, many packs of raw silk, Indian cloth, and thread stockings; these things being the principal part of her cargo. We stood out S.W. by S. all the night following. The next day being come, we transported on board our ship the chief part of her lading. In her hold we found some rigging, as had been told us by Nicholas Moreno, our pilot, taken in the former vessel off of Guayaquil, but the greatest part of the hold was full of timber, We took out of her also some Osnaburgs, of which we made top-gallant sails, as shall be said hereafter. It was now nineteen days, as they told us, since they had set sail from Guayaquil, and then they had only heard there of our exploits before Panama, but did not so much as think of our coming so far to the southward, which did not give them the least suspicion of us, though they had seen us for the space of two or three days before at sea, and always steering after them, otherwise they had made for the land, and endeavoured to escape our hands. The next morning, likewise, we continued to take in the remaining part of what goods we desired out of our prize. When we had done we sent most of our prisoners on board the said vessel, and left only their foremast standing, all the rest being cut down by the board. We gave them a foresail to sail withal, all their own water, and some of our flour to serve them for provisions, and thus we turned them away, as not caring to be troubled or encumbered with too many of their company. Notwithstanding we detained still several of the chief of our prisoners. Such were Don Thomas de Argandona, who was commander of the vessel taken before Guayaquil, Don Christoval, and Don Baltazar, both gentlemen of quality, taken with him, Captain Peralta, Captain Juan Moreno, the pilot, and twelve slaves, of whom we intended to make good use, to do the drudgery of our ship. At this time I reckoned that we were about the distance of thirty-five leagues, little more or less, from land, moreover, by an observation made this day, we found lat. 7° 1' S. Our plunder being over, and our prize turned away, we sold both chests, boxes, and several other things at the mast, by the voice of a crier. On the following day we stood S.S.W. and S.W. by S. all day long. That day one of our company died, named Robert Montgomery, the same man who was shot by the negligence of one of our own men with a pistol through the leg at the taking of the vessel before Guayaquil, as was mentioned above. We had an observation also this day, by which we now found lat. 7° 26' S. On the same day likewise we made a dividend, and shared all the booty taken in the last prize. This being done, we hoisted into our ship the launch which we had taken in her, as being useful to us. All these days last past it was observed that we had every morning a dark cloud in the sky, the which in the North Sea would certainly foretell a storm, but here it always blew over. Wednesday, September 8th, in the morning, we threw our dead man above-mentioned into the sea, and gave him three French volleys for his funeral ceremony. In the night before this day, we saw a light belonging to some vessel at sea, but we stood away from it, as not desiring to see any more sails to hinder us in our voyage towards Arica., whither now we were designed. This light was undoubtedly from some ship to leeward of us, but on the next morning we could descry no sail. Here I judged we had made a S.W. by S. way from Paita, and by an observation found 8° 00' S. _________________ 1 This is no doubt the native craft Balsa still used in the vicinity. It is a raft bearing one or two large sails and provided with sliding keels in the shape of large planks drawn up or let down according to circumstances. Perhaps the earliest example of the use of sliding keels. 2 See note on p. 345. |