| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

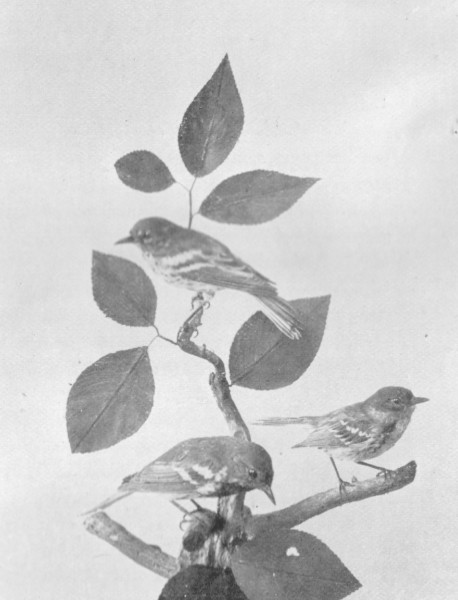

| "Gloomy winter's now awa', Saft the westlin breezes blaw; 'Mang the birks o' Stanley-shaw The mavis sings fu' cheerie O" Tannabill. APRIL THE mavis of the poet is not an American bird, but the vernal gladness overspreads the world, and each country has its own peculiar songsters to give a welcome to the Hoar Winter's blooming child, delightful Spring!" By the force of habit and the influence of names, the appearance of spring in March, however genuine, always seems preliminary, and not till April do we feel ourselves fully launched upon the new course of things. The month was ushered in with the first full song of the white-throated sparrows, for which I have been impatiently waiting; and so generally throughout the Park did their strain fall upon my ear, that it was evidently the result of clever prearrangement. It is quite aptly called "peabody bird," as the main part of its song has a striking resemblance to the reiterated sound of peabody, peabody, peabody, with the accent on the first syllable, and commonly a downward inflection on the following syllables. This peculiarity, and a genuine whistling quality of tone, unlike that of any other species, are sufficient to identify the bird, even if one had never heard the song before. Without the depth of sentiment and rich volume of sound that distinguish the fox sparrow, it is quite characteristic and cheery. Nor is it less pleasing because of the creature's evident reluctance to have spectators at the performance; for it precipitately retires from the scene when it sees any one approaching; but if you linger in the vicinity unobserved, you may often enjoy quite a protracted recital. In this respect how different from the song sparrow, which can always be relied upon to take a most conspicuous position on a bush or tree, as if singing to all the world; and yet so artless withal, as rather to enhance the effect. As the season advances the colors of the white-throated sparrow brighten perceptibly, and many of the specimens become quite attractive before they leave for their summer home. The disappearance of a bird's bright colors in autumn seems to be nature's safeguard. The goldfinch would be a "shining mark" for its enemies in the leafless publicity of a winter landscape, were it not for the substitution of a quiet suit of brown for its brilliant summer dress. April is the first great harvest month for the ornithologist. The winter species are still loath to leave, and the summer residents and migrants are coming in considerable numbers. The golden-winged woodpeckers are becoming quite numerous, and during the first week the golden-crowned kinglets, which seemed to be entirely absent for several weeks, returned in great force, having probably been driven southward by the intense cold. The brown creeper, which seems at first to have no affiliations among its kind, and to do business entirely on its own account, but which I have commonly found to be within hailing distance of kinglets or chickadees, also left this region just as suddenly as the gold-crests about the middle of January, and reappeared the very same day in April, and almost within stone's throw, which indicates that, although they are not garrulous friends, there is a very tacit understanding between them. Amid the singing (or attempts to sing) of all the other birds, I heard a very musical twitter from a nuthatch, quite contrary to his custom, and apparently prompted by the desire to be in fashion. Among all the woodland choir the phoebe alone, for good and sufficient reason, as yet remains as dumb as an oyster.  Golden-Crowned Kinglets A few days after the return of the "gold-crest" I discovered a species of kinglet that I had never seen before — the ruby-crowned, somewhat more rare, and, as it seemed to me, though perhaps from the circumstance of novelty, more beautiful than even the "gold-crest." The two kinglets are of the same size (about four inches long), and the smallest of all our birds except the humming-bird. With the same general coloring as the other, the ruby-crowned has a suffusion of yellow, and, instead of the black and yellow markings on the head, the male has a deep red flame on the crown. But the specification of its coloring does not touch the core of its daintiness as shown in figure and motion. The habits of the two are the same, and under the circumstance of its not being very much rarer than the "gold-crest" it is a singular fact that perhaps in not more than three or four instances has its nest ever been discovered. My attention was first called to the bird by hearing a remarkably clear and unfamiliar song at a distance, and I started inevitably to discover its origin. The characteristic part of the song is a triplet of tones represented by the first, third, and fifth of the scale (these intervals being remarkably precise), uttered in rapid succession and repeated three or four times. The introduction of the song is an indescribable and intricate modulation, but the triplet was never absent, and indeed was sometimes given without the introduction. It seems almost incredible that so full and resonant a tone can issue from so tiny a throat. For a few days this was the finest songster in the Park, rivalling the white-throated and the fox sparrows in its delicious clearness; but the bird made only a flying visit, and was soon gone. Its greater rarity, as compared with the "gold-crest," is largely due to the fact that, whereas the latter is a winter resident, the former spends the winter farther south, and is seldom to be seen except in its semi-annual transit. I have also heard from the "gold-crest" what was more than a twitter, but less than a song; but either it does not awake to the full sense of its musical responsibility so early in the year as the ruby-crowned, or else it is far less gifted. Related to the kinglets, but a much rarer species, is the beautiful and irrepressible little blue-gray gnat-catcher (found on one occasion in the Ramble), only four and a half inches long, in quiet tones of grayish-blue above, and white beneath, of delicate mould, and in many ways suggestive of a tiny mocking-bird. Any one can imagine the turbulence, not to say agony, of a bird which, like this gnat-catcher, has a body that is evidently several sizes too small for its soul, necessitating a constant escape of delirious song and motion. The discovery threw me into quite a flutter, as it was my first and long-anticipated view of the elegant creature. He entertained me for nearly half an hour in a most confidential manner with his continuous warble, graceful posturings, and airy flights, diving hither and thither for insects on the wing in the manner of a true flycatcher. The song is characterized by impetuosity rather than sweetness, as it is mostly a subdued reminiscence of the catbird's heterogeneous vagaries. About this time I found a mysterious stranger on three different occasions, always by itself: its plumage black, but apparently not iridescent, smaller than the crow-blackbird, and yet not likely to be the rusty grackle, whose plumage at this season would hardly be a uniform black. The tone was more musical than the grackle's, and yet had a suggestion of it. The probability seems to be that it was one of the imported starlings that have been turned loose, and had perhaps lost track of its fellows. I almost wish I had not seen it, if it is not to show itself again; for it is a most exasperating pleasure to find an unidentifiable specimen. I note the arrival of that humblest and most familiar of all sparrows, — the ubiquitous "chipper." It certainly cannot be called a singer, and its familiar note is commonly too strident to be very musical; but it is a harmless drop of sound, even among the vocalists of June, and pleasantly fills a niche in the empty spaces of July and August. In appearance it is always refreshingly neat, not to say spruce, and unpretentious; and by being neither over-timid nor bold, it always holds itself at an interesting distance. This is said to be the only one of the sparrows that sometimes builds its nest in trees, all the other species (except, perhaps, the tree sparrow) on the ground or in bushes. From its nest being commonly lined with horsehair it gets the name of "hair-bird." Almost a fac-simile, enlarged, of the chipping sparrow, with a bright chestnut crown, and aptly called the "arctic chipper," from its breeding only in arctic regions, is a bird more commonly known as the tree sparrow, but with little propriety in the prefix, as it is oftener found on the ground than elsewhere, and does not commonly nest in trees. It is a denizen of our woods in winter, although I have seen it in the Ramble only during migration. It was then almost silent, but in its summer haunts it is said to be a very pleasing singer. In the case of species so nearly identical as the common and the Arctic chippers, it would be very interesting to know wherein consists that subtle temperamental distinction that drives them to such diverse latitudes. One of the largest and most important groups of birds in this country is the one known as the "warblers." Especially graceful in form and motion, with brilliant plumage, pleasing if not remarkable songsters, and in their habits thoroughly beneficial to vegetation, the warblers deservedly rank high in the estimation of bird lovers. The anatomical characteristics which determine the family relationship of this group could not be detected at a distance of five feet, and yet there are other and more palpable resemblances which would lead even a casual observer to associate them together. The distinctive points of this family, as viewed by the field ornithologist, can be best presented and remembered by a brief comparison of warblers and finches, which are the two largest families in America. Warblers are uniformly small — from four to six and a half inches in length; finches are not so uniform in size, but average larger, varying from five to nine inches in length. In general the finches are rather plainly colored (a rule that has several notable exceptions), while the warblers, as a class, are strikingly beautiful. Any feathery bit of black, white, blue, and gold flashing among the branches is likely to be a warbler, for there are few other specimens so minute and beautiful. Some of the finches — for example, several of the sparrows — have no merit as songsters, but very many of them are quite musical, and some are famous, so that as a family they are superior vocalists. The warblers are inferior in this respect, and the name of "warbler," as designating a conspicuous trait of the family, is a misnomer. In many of the species the "song" is little more than the rapid reiteration of a single note; in others there is some degree of modulation and accent (as in the black-throated greens), which is very pleasing and vivacious, and more fitly called a melody; but none of them give a suggestion of such warbling as one hears from the purple finch, the goldfinch, the rose-breasted grosbeak, or the fox sparrow; and I am quite unable to understand the extravagant language some writers use in commendation of the musical qualities of these birds, which in other respects are unsurpassed by any other species. The finches are the more musical; warblers more graceful in movement, and more charming in form and plumage. In temperament finches are more phlegmatic, warblers more nervous. There is an eternal restlessness about a warbler, in marked contrast to the comparatively "low-pressure" organism of a finch. The salient traits of the finch remind one of the German nationality, while the "warblers" are doubtless of avian-French descent. The finches are chiefly granivorous (vegetarian), the warblers chiefly insectivorous. For this reason finches are not so migratory as warblers, whose resources of food are almost entirely swept away by cold weather, so that there is only one warbler (the yellow-rump) that can be found in the Northern States during the winter. The scientific designation of the warblers as sylvicolidæ (living in the woods), although not profoundly descriptive, is not misleading, and points to an evident characteristic of the class. They are more retiring than many other species, and are found in woods and groves rather than by the wayside or in the open pasture. In this region the finch and warbler families are equally represented by about forty species in each. Throughout North America there are twice as many finches as warblers, one hundred and twenty-three to sixty-two, and in the world five hundred species of finches (the largest of all families), and upward of one hundred species of warblers. These points of comparison touch upon the most important aspects in the life-history of the two families. The first week in the month brought the first warbler of the season, viz.: the pine-creeper, which is usually the forerunner of the family. It is about six inches long: olive above, throat and breast bright yellow, passing into white beneath, and two white wing-bars — chiefly a denizen of pine woods; and whoever has found it in its summer resorts will thereafter always associate its simple, sweet, and drowsy song with the smell of pines in a sultry day. It often runs along the branches, an unusual occurrence for any bird, and especially for warblers, whose nervous temperament commonly puts them on the wing, as the most congenial method of locomotion. Like the nuthatch the pine-creeper often clings to the tree-trunk. It is probably only seen as a migrant in this region, which is true of about half of the warblers, their summer home being in northern New England and beyond. The reader of any ornithological literature that is not technically scientific, will observe the alternating occurrence of "he" and "it," "who" and "which," in speaking of a bird. This results from the writer's effort to satisfy the demands of sentiment on the one side, and of grammar on the other. For it is very distasteful to any bird-lover to degrade his friends to the impersonality of the neuter gender, and when speaking of a favorite species he boldly ignores grammatical rules. He is thus constantly "in a strait betwixt two," reminding me of a good Catholic friend with whom I once boarded, who compromised the claims of conscience imposed by his religious belief and the requirements of hospitality by providing meat dinners on alternate Fridays! In company, as usual, with the pine-creeper, came another and more interesting warbler, the "red-poll," so called from a very pretty chestnut-red spot on the top or the head. It is also entirely yellow beneath. But the readiest mark of distinction from almost all other birds is its habit of constantly flirting the tail, like the phoebe. This is an infallible test of a red-poll. Like the flycatcher, too, they often dart into the air for insects. What the red-poll may be as a songster when it gets to Canada, I do not know; for the present it has only a single note of luscious quality, which is several times repeated. Altogether it is a very attractive little creature, with its bright colors and vivacious ways, and I am only sorry that New York is not cool enough to induce it to remain and settle down for the summer. Close upon the heels of these warblers — or what would be their heels if they had been so provided — comes a migrant woodpecker, the yellow-bellied — black, white, and brown above, yellowish beneath, with a crimson patch on the crown. The easiest standard of measure for moderate-sized birds is the robin, which is familiar to everyone; so I shall do better to say that this new-comer is a little smaller than a robin, which gives a more accurate idea than to say it is eight and a half inches long. It is interesting to watch him as he clings for a long time to one spot on a tree, boring deep holes, though it is not quite certain what he is after. Sometimes too he will strip off large pieces of bark from the trees, it is said, for the purpose of feeding on the inner bark. Nuthatches are a sort of superficial woodpeckers, extracting only the insects and larvæ that find lodgement in the cracks of the bark. At this time I heard an incipient song from the crossbills, both while they were occupied in the evergreens, and on the wing; having a delicious quality in the tone, the promise of fine effects in the song-season. But the most important event of this same day, and indeed of the month, was the discovery of the hermit thrush, not for its rarity, but as a noble member of a most distinguished family. This is a text on which every bird-lover delights to discourse, for the thrush among the birds is like the rose among the flowers — a masterpiece of its kind. In organization and vocal gifts it has a conceded pre-eminence, and the three species (wood, Wilson, and hermit) are the prima-donnas of the forest. The hermit is only a migrant, and is commonly silent till he reaches home in northern New England and Canada; but in full song his voice is rich and sonorous; and a softer tone, which I heard soon after his arrival, was like the finest thread of pure gold. The plumage of this species is called in the books an olive-brown, but it has an indescribable softness of tone, and a quiet elegance that makes the "belle of the winter" (the cardinal), look simply gaudy, while in form and movement the bird betrays a subtle and unconscious evidence of high-breeding, and that natural touch of exclusiveness which any such creature must inevitably have; like the delicate but impenetrable atmosphere surrounding every finely grained individual. This is attributing a good deal to the hermit thrush, but the testimony of those who have felt the influence of this mystical reserve is of more authority than the opinion of those who have not. The delight caused by the return of many a bird in spring is in large measure due to the associated scenes of other times that are recalled by its appearance. Everyone in the country who has wandered through the woods at the twilight hour, listening to the choristers that sing their varied farewell to the day and drop off one by one into silence, feels the force of the poet's lines: "Each bird gives o'er its note, the thrush alone Fills the cool grove when all the rest are gone." It may well have been some noble song like the robin's cheerful warble, or the more glorious chant of the wood thrush, heard among the branches in the cool of the day, that inspired the poetic utterance of the Psalmist, so sensitive to every natural beauty — "Thou makest the outgoings of the morning and evening to rejoice." (For "rejoice" the marginal reading is "sing," which gives color to the foregoing ornithological exegesis.) A change has come over the spirit of the phoebe, which for the past few days has been stationed like a black-capped sentinel on the point of a branch overhanging the water. For a week after its arrival it sat silent, solitary, and evidently dejected; but this morning it is all animation, and cheerily calling its own name or that of its mate as it flies hither and thither. A case of human nature in bird-form. When the migration-time comes it is usual in this as in most of the other species for the male to arrive first, his gentle consort, proverbially tardy, putting in her appearance several days later. It is hard to imagine why they cannot agree to take the journey together, as the matrimonial compact does not expire by limitation with the phoebe, as it does with many others, to be renewed annually. That it is not the result of a "tiff" just before starting seems proved by the delight expressed at the reunion. We seem forced to the conclusion that this conduct results from one of the inscrutable eccentricities of the feminine intellect. And it is not a little singular that a trait in one of the sexes of constitutional unpreparedness to start on time should be so prevalent throughout the animal kingdom. That

the volume of

life is steadily

increasing, not only in numbers but in variety, is evidenced by the

following list of birds seen on the 10th of the month: flicker, brown

creeper, fox sparrow, white-throat, song sparrow, ruby-crowned

kinglet, gold-crest, goldfinch (which has almost regained its summer

plumage), snow-bird, robin, red-bellied woodpecker, phoebe,

crossbill, nuthatch, crow blackbird, hermit thrush, and pine-creeper

— a miscellaneous assortment of winter residents, summer

residents, and migrants, and representative of eight distinct

families  Phoebe Frequently one hears a loud, clear, and peculiar whistle, not on one pitch, like the tone of the white-throat, but with an upward inflection, like the effect produced in whistling by giving to the tone a short and quick stroke upward. After a succession of such tones comes another series with a corresponding downward inflection and more rapid, the whole effect represented thus:  By one who knows the note of the cardinal grosbeak this will be recognized as an accurate ocular description, and for one who has never heard it, I can say with confidence that it is not more cabalistic and inadequate than the majority of efforts to put a bird's notes into black and white. It is the most characteristic and promising call-note I have ever heard. Reference will be made to the song later. In this connection it may be said that perhaps the commonest error in song-description is the frequent allusion of all writers to a bird's trill — a thing very seldom heard. This is a convenient word for describing a peculiarly brilliant and beautiful phase of its vocalization, and with a clear understanding of its general inaccuracy I suppose it is admissible to perpetuate the monosyllabic falsehood. From now on it is an experience of parting with old friends as well as greeting new ones. By the middle of the month the fox sparrows, so abundant and singing so freely during all their stay, had quite disappeared. Coming out of a cloudy sky with an avalanche of song, they leave one of the pleasantest and most distinct memories of early spring, like the anemone, and have passed on into an anticipation of the next year. Very companionable with all other birds, they had a delightful way of making themselves quite at home during their short visit, without becoming obnoxious, like the grackles; the best sort of company, that comes to entertain as well as to be entertained, so that when they are gone you feel that the obligation is rather on your own side. Occasionally it is worth while to glance even at a flock of English sparrows, for one morning I found among them a purple finch. To be sure, sparrows are finches, and, as the German expressed it, "birds mit one fedder go mit demselves;" but cousinship is a bond that is conveniently played "fast and loose," according to the social plane of the parties themselves, and birds can be just as aristocratic and exclusive as their human neighbors. In full plumage the purple finch is more carmine than purple, but at this season it is quite nondescript, as if a large sparrow had been dipped in a purplish carmine tincture and then been washed off in streaks. It was very shy at my approach, and between my anxiety to get as near as possible, and my fear that it would be frightened quite away, I was in a strait. As it paused a moment, in flying from tree to tree, it lured me on with that delicious carol that has established its reputation as one of the finest of finch songsters — a warble that suggests that of the robin and bluebird, but more prolonged. Some one has likened its song to that of the warbling vireo, but the tone is far more full and rich than the vireo's. Both the warbling and the red-eyed vireo make one feel that they have not the sweetest temper in the world, but the purple finch is evidently one of the most cordial and good-natured of creatures. Now, too, The frogs renew the croaks of their loquacious race; " — the

white-breasted

swallows being the

earliest of the family to appear in spring. They are only about six

inches long; but the wide sweep of the wings and the pure white of

the body beneath make them very conspicuous; while the lustrous

steel-green of the upper side becomes visible when they sail near the

ground. There is an ecstasy or intoxication in the flight of the

swallows, as a large number of them perform their bewildering and

tireless evolutions over stream or lake, that affords one of the most

pleasing and animated scenes of inland nature.

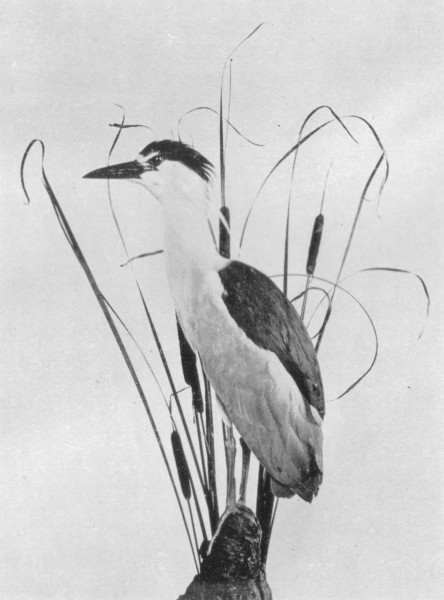

On the same day as the swallows, came the third warbler, the "yellow-rump," the most abundant in the migrations, and the only one of the family that lingers in this latitude through the winter, although the great majority even of this species go south every fall. Less brilliant than the "red-poll," it is hardly less dressy, in black and white, with four yellow spots, on head, sides, and rump. The first three are variable, sometimes wanting, but the persistence and prominence of the fourth spot gives the name to the species. This has the habit of perching and flying higher than most of the family; and there is nothing more aggravating than to have a small specimen which you are unfamiliar with remain near the top of a tree, move about incessantly, and, just as you have reached a coigne of vantage, coolly fly off out of sight. One morning, in a driving rain-storm, I started out to explore the upper and less frequented part of the Park. With an ardor that my moist surroundings could not dampen, it was still especially gratifying to find something new, for I soon discovered a (to me) unfamiliar species of nuthatch, the red-breasted. The only other one in this region, the white-breasted, can generally be found in all our woods through the winter, and the red-breasted are probably rarer only in the sense that they winter farther south, and are with us a shorter time. If the white breasted is plain, the red-breasted is plainer. But that makes little difference to the naturalist; he has conquered another world in finding a new species, and beauty is sometimes a superfluity. The nuthatches are peculiar fellows in that they have little fear, but a great deal of curiosity. In a very pert and comical manner one will stretch out its neck, cock its head on one side, and coolly examine a person passing by. But the difference between impudent boldness and artless inquisitiveness is as easily distinguishable in a bird as in a human being. This particular specimen seemed to show an unwonted degree of curiosity in watching me; and doubtless, from a bird's point of view, a person under an umbrella, looking through an opera-glass, is a somewhat startling piece of mechanism that might well astonish a Canadian nuthatch. In habits, range, and note the two species closely resemble each other. The red-breasted is smaller, has a black stripe on the side of the face, and is of a pale rusty color beneath; whereas the other has a clear white face and is nearly white beneath. It is a strange habit of the nuthatches that they rest and even sleep clinging to the tree-trunk head downward. One morning, as I was watching the pranks of a "yellow-rump," darting hither and thither, apparently as much from exuberance of spirits as with foraging intent, my attention was called to a large pearl and white colored bird high in a tree on the border of the Lake, a jet black stripe on its head and back, feet and legs brightly colored, and its long dark bill sunk in the feathers of the breast, as if fast asleep. In its immovable position and bare surroundings it was a most picturesque emblem of solitude, one of those slight but suggestive touches in nature that one is constantly stumbling upon. In my helpless ignorance of what it was, I grasped at a straw, and asked a policeman near by if he could enlighten me. Now, experience has taught me that, like many other people in the world, a policeman feels a deep sense of humiliation if obliged to confess that he is unable to answer any question propounded to him; and this one in particular, who was not better than his fathers, promptly and with half contemptuous tone told me it was a duck. His assurance was of course not lessened by the fact that he had not fully seen the bird. At first I felt crushed by his wisdom and my own stupidity, forgetting for the instant that the creature in question had no more the "build" of a duck than of an owl; but I soon rallied sufficiently to ask him if ducks roost in trees. This flank fire routed him, and, recovering my self-respect, I applied to a more infallible source of scientific information — the Natural History Museum — and found the bird to be a black-crowned night heron. Lest

any one, wise in

the ways of

birds, should accuse me of an egregious slip in ornithological lore,

I hasten to confess that ducks sometimes do roost in trees; indeed, one

species finds its

nest in the

holes of trees. Yet I was fully justified in the bold front I

presented to this guardian of the peace. I challenged him with

the rule — the only weapon that a person of his scientific

attainments could safely use. An exception is always a dangerous

article in the hands of the inexperienced.  Black-Crowned Night Heron

The herons are one of several mournfully poetic families of birds that gracefully adorn many a landscape, real and pictured. The largest and most elegant of this family are the great blue and the great white herons, found here and there in the vicinity of water, either singly or in small flocks. The night heron, a pair of which remained several weeks near the spot where I found it, and said to have nested in the neighborhood, is much more abundant, being often found in immense colonies of hundreds and thousands, where a single tree is said sometimes to contain a dozen nests. Southern New England contains several such heronries. The entire feathered race divides itself easily and naturally into Land Birds and Water Birds. The former division contains all the best-known species — song-birds, woodpeckers, owls, hawks, eagles, etc. — from their greater proximity to man. But the water-birds, with their distinctive forms and habits, are not less interesting objects of study, and, although without the attractive elements of song and (in comparatively few species) brilliant plumage, include many of our most picturesque and graceful specimens. In any region having an extensive waterfront, especially if it be marine, the water-birds are also numerically important, as, for example, in the New England States, where they constitute about two-fifths of the entire avifauna. They are of two quite distinct sorts, known as "waders" and "swimmers." The waders are chiefly shore-birds, commonly found on the borders of the ocean, lake, bog, or stream, or wading in the shallows where they find the animal food on which they chiefly subsist, and which they are so evidently adapted to procure, by their long bills and necks, slender bodies, and long legs. The most beautiful of waterfowl are in this class, such as the cranes, storks, and herons of the Northern States, and the gorgeous flamingoes of Florida, all of these about four feet in length and several feet high. The "swimmers" are of a different type, being generally thick-set, short-limbed, and web-footed — an organization that makes them as much and often more at home in the water than on the wing. The prevailing type of this class is illustrated in swans, ducks, gulls, and loons, while a few of the families, like the terns and petrels, are more aerial in form. Nature shades off one class of her creatures into another, and there is no impassable gulf fixed between "waders" and "swimmers," however pronouncedly different the two types are in general. Even among the "waders" there are different degrees of the web-foot, from the total absence of it in many, up to the avocet, which is almost fully web-footed. Nature seems very enigmatical in offering the largest encouragement to man's efforts to apprehend the scheme of creation, and at the same time apparently mocking his labors by her impenetrable mysteries. Yet this contradiction has its advantage. Without success in his research, man would become discouraged; and without failure, conceited. Another of the "waders," appearing in the Park soon after the herons, is the spotted sandpiper. The sandpipers are a family of small and plainly colored birds, most of the species frequenting the sea-coast or salt-marshes; but the spotted and solitary sandpipers are freshwater birds. A pair of the former remained at the Lake several days. It is from seven to eight inches long, dark above, and beneath white, thickly spotted with dark. Their flight is quite peculiar. With one quick stroke of the wings they can propel themselves a long distance, and, by repeating at intervals the single vibration, they appear to be floating in air, as with motionless wing they speed along close to the water. When standing on the ground they have a ludicrous trick of ducking the head and jerking the body, the purpose of which is quite unaccountable, a habit that has given them the expressive, if not elegant, sobriquet of "teetertail" or "tip-up." The long, thin anatomy of the waders gives them a somewhat ungainly appearance as compared with the flowing outlines of the land-birds. Yet the water-fowl have a strong and unique fascination, in part doubtless due to the reflection of the water's own mysterious influence. The next warbler to arrive was the well-known but always welcome "black-and-white creeper," whose name is a polysyllabic statement of its plumage and method of progression as it scrambles about on the trunks and branches. It seldom occurs to one, as he watches the sprightly movements and graceful posturings of this and so many other species, intent only upon satisfying their hunger, what an incessant and invaluable service they are thus rendering to man himself. We are forced to the conclusion that the feathered tribe is about the most ingenious combination of utility and ornament ever devised by the Creator. A few feet from where this little fellow unconsciously introduced himself to me (I say himself purposely, for his graceful complement was lagging behind somewhere in South Carolina) a suspicious rustle in the low bushes betrayed a larger bird, which took flight as I approached; its size, a little smaller than the robin, black body, chestnut sides, and the "white feather" it shows in the tail as it flies, proved it to be the chewink or towhee bunting. It is not yet in song, and allusion will be made to it again. A most humble specimen of a humble group is the field sparrow, considerably like the "chipper," but its markings even less distinctive, the most significant feature being the reddish tinge of the bill. Its note, too, is quite different from the familiar sound of the chipping sparrow. While not an uncommon bird, its shyness and resemblance to its bolder and more noisy congener make it a comparatively unfamiliar species. Close upon the field sparrow I stumbled upon an unusually beautiful warbler, which one may well be enthusiastic about, for it is one of the daintiest of the family, bound literally in blue and gold and white, and in form and coloring one could hardly imagine anything more exquisite. A light ashy-blue spreads over the upper part of the body and wings, finely sprinkled with gold in the centre of the back, while beneath it is snow-white except for the yellow and brownish band across the breast. This is called the "blue yellow-back," and is one of the smallest of the warbler group. It soon became quite common, especially at a certain spot where the opening buds of the shrubbery proved to be particularly delectable. It was a picture not to be forgotten, as in their rich colors they swayed on the tall, slender branches, and with inimitable grace assumed every variety of posture in plucking the fresh leaves. A stuffed specimen of such a creature is an utter caricature of the original. If each night, from about the middle of April to the middle of May, one's vision could sweep through the entire range of sky from New England to Mexico, what bird-clouds he would see rolling up from the south, here and there settling to the ground, rising again, and pushing northward. One of the largest "cloudbursts" of this sort in the Ramble was on the 29th, which was a red-letter day for the ornithologist, transforming the Park into a veritable aviary. Red-polls, black-and-white creepers, and yellow-rumps were swarming among the larches, while in the adjoining trees a sprightly and characteristic song called attention to a flock of brilliant warblers that I had been several days looking for — the black-throated greens. Blue yellow-backs were fluttering here and there, while a single Canada nuthatch looked quite out of place amid the gorgeous array. At a short distance was the Maryland yellow-throat, the black-throated blue, and the golden-crowned warbler or oven-bird. Four species of sparrows, three of the thrushes (the Wilson and wood thrushes having just arrived), and many of the usual varieties made the number twenty-three that I saw that morning. Fortunately most of the new arrivals were not yet in song, which would have made the effect a little too luxurious. The mere sight of all the gay throng was quite sufficient for one day.  Black-Throated Green Warblers On the same morning a large flock of purple finches were discovered, mute and motionless in a tree. There was no excuse for their silence, as they were already in song nearly three weeks before. The most abundant warbler is the yellow-rump, and quite conspicuous with the two gold badges on the breast; while a more dashing beauty is the black-throated green, its throat and breast like black velvet, the sides of the head a deep rich yellow, the back olive-green, and white beneath. Its song is more varied than that of many of the warblers, and in all respects it is one of the most attractive of the group. In their summer homes their preference is for the pines and cedars, but in the migrations the distinctive tastes of birds are not so evident. The following morning added two more to the month's list, although they probably came in the "wave" of the day before. Passing the Lake, I heard the brown thrush or thrasher "welcoming the day," and I ventured to take a little of the greeting to myself. He was high in a tree, and in the heterogeneous vocal business as usual, as if sampling all the melodies he could remember. In its miscellaneous character the song is much like the catbird's pot-pourri, but with richer tone. The thrasher is the other thrushes' "big brother," as his plumage and voice plainly show. And, lastly, one of the smallest of warblers, only four and a half inches long, olive above, with brick-red spots on the back, and bright yellow beneath, spotted with black, called the prairie warbler, possibly because its taste is more for open land than for the woods. The following is the summary for April, the majority of the forty species having been at one time or another quite numerous in the Park: the grackle, robin, snowbird, European goldfinch, white-throat, fox sparrow, song sparrow, flicker, phoebe, white-breasted nuthatch, gold-crest, brown creeper, crow, pine warbler, yellow-bellied woodpecker, cardinal, hermit thrush, chipper, crossbill, ruby-crowned kinglet, American goldfinch, red-poll, purple finch, white-breasted swallow, yellow-rump, red-breasted nuthatch, night heron, black-and-white creeper, towhee bunting, field sparrow, blue yellow-back, spotted sandpiper, Wilson thrush, wood thrush, black-throated green warbler, black-throated blue, Maryland yellow-throat, golden-crowned warbler, thrasher, and prairie warbler. Many an ornithologist throughout the country can report a longer and more varied list for April than mine, with its paucity of water birds, and with none of the game birds, nor of the birds of prey. But certainly in the foregoing record is ample subject-matter wherein to find either relaxation or instructive stimulus. It can hardly be doubted that" far more would make this pursuit an avocation, if they realized that the opportunities therefor lay so conveniently at hand. Flowers and birds are among the winged ministrants, rather than among the stern task-masters, of mankind. Neither abstruse nor profound, they are certainly unexcelled among the works of nature for affording a restful modulation of thought, and for quickly resolving a tangled state of mind from discord into harmony. |