| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Ancient Tales and Folk-Lore of Japan Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

| THE TEMPLE OF THE AWABI IN

Noto Province there is a small fishing-village called Nanao. It is at

the

extreme northern end of the mainland. There is nothing opposite until

one

reaches either Korea or the Siberian coast — except the small rocky

islands

which are everywhere in Japan, surrounding as it were by an outer

fringe the

land proper of Japan itself. Nanao

contains not more than five hundred souls. Many years ago the place was

devastated by an earthquake and a terrific storm, which between them

destroyed

nearly the whole village and killed half of the people. On

the morning after this terrible visitation, it was seen that the

geographical

situation had changed. Opposite Nanao, some two miles from the land,

had arisen

a rocky island about a mile in circumference. The sea was muddy and

yellow. The

people surviving were so overcome and awed that none ventured into a

boat for

nearly a month afterwards; indeed, most of the boats had been

destroyed. Being

Japanese, they took things philosophically. Every one helped some

other, and

within a month the village looked much as it had looked before;

smaller, and

less populated, perhaps, but managing itself unassisted by the outside

world.

Indeed, all the neighbouring villages had suffered much in the same

way, and

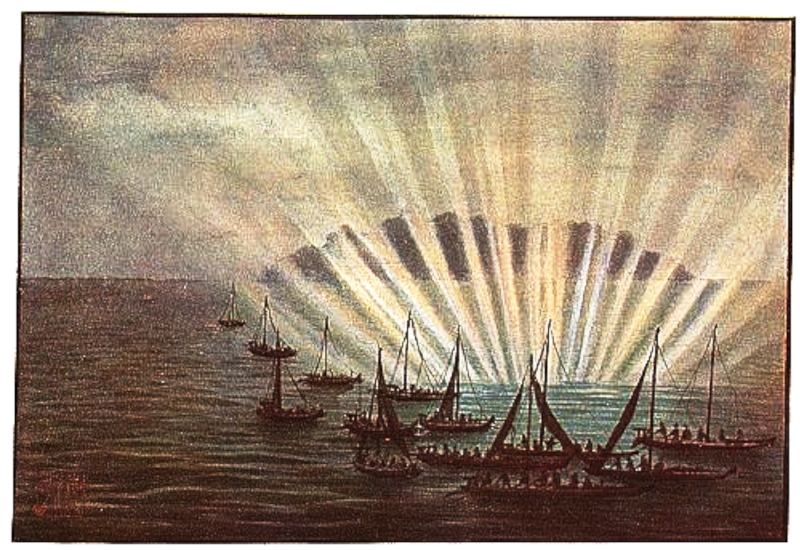

after the manner of ants had put things right again. The fishermen of Nanao arranged that their first fishing expedition should be taken together, two days before the 'Bon.' They would first go and inspect the new island, and then continue out to sea for a few miles, to find if there were still as many tai fish on their favourite ground as there used to be.  The Fishermen are Astonished at the Extraordinary Light It

would be a day of intense interest, and the villages of some fifty

miles of

coast had all decided to make their ventures simultaneously, each

village

trying its own grounds, of course, but all starting at the same time,

with a

view of eventually reporting to each other the condition of things with

regard

to fish, for mutual assistance is a strong characteristic in the

Japanese when

trouble overcomes them. At

the appointed time two days before the festival the fishermen started

from

Nanao. There were thirteen boats. They visited first the new island,

which

proved to be simply a large rock. There were many rock fish, such as

wrasse and

sea-perch, about it; but beyond that there was nothing remarkable. It

had not

had time to gather many shell-fish on its surface, and there was but

little

edible seaweed as yet. So the thirteen boats went farther to sea, to

discover

what had occurred to their old and excellent tai grounds. These

were found to produce just about what they used to produce in the days

before

the earthquake; but the fishermen were not able to stay long enough to

make a

thorough test. They had meant to be away all night; but at dusk the sky

gave

every appearance of a storm: so they pulled up their anchors and made

for home.

As

they came close to the new island they were surprised to see, on one

side of

it, the water for the space of 240 feet square lit up with a strange

light. The

light seemed to come from the bottom of the sea, and in spite of the

darkness

the water was transparent. The fishermen, very much astonished, stopped

to gaze

down into the blue waters. They could see fish swimming about in

thousands; but

the depth was too great for them to see the bottom, and so they gave

rein to

all kinds of superstitious ideas as to the cause of the light, and

talked from

one boat to the other about it. A few minutes afterwards they had

shipped their

immense paddling oars and all was quiet. Then they heard rumbling

noises at the

bottom of the sea, and this filled them with consternation — they

feared

another eruption. The oars were put out again, and to say that they

went fast

would in no way convey an idea of the pace that the men made their

boats travel

over the two miles between the mainland and the island. Their

homes were reached well before the storm came on; but the storm lasted

for

fully two days, and the fishermen were unable to leave the shore. As

the sea calmed down and the villagers were looking out, on the third

day cause

for astonishment came. Shooting out of the sea near the island rock

were rays

that seemed to come from a sun in the bottom of the sea. All the

village

congregated on the beach to see this extraordinary spectacle, which was

discussed far into the night. Not

even the old priest could throw any light on the subject. Consequently,

the

fishermen became more and more scared, and few of them were ready to

venture to

sea next day; though it was the time for the magnificent sawara (king

mackerel), only one boat left the shore, and that belonged to Master

Kansuke, a

fisherman of some fifty years of age, who, with his son Matakichi, a

youth of

eighteen and a most faithful son, was always to the fore when anything

out of

the common had to be done. Kansuke

had been the acknowledged bold fisherman of Nanao, the leader in all

things

since most could remember, and his faithful and devoted son had

followed him

from the age of twelve through many perils; so that no one was

astonished to

see their boat leave alone. They

went first to the tai grounds and fished there during the night,

catching some

thirty odd tai between them, the average weight of which would be four

pounds.

Towards break of day another storm showed on the horizon. Kansuke

pulled up his

anchor and started for home, hoping to take in a hobo line which he had

dropped

overboard near the rocky island on his way out — a line holding some

two

hundred hooks. They had reached the island and hauled in nearly the

whole line

when the rising sea caused Kansuke to lose his balance and fall

overboard. Usually

the old man would soon have found it an easy matter to scramble back

into the

boat. On this occasion, however, his head did not appear above water;

and so

his son jumped in to rescue his father. He dived into water which

almost

dazzled him, for bright rays were shooting through it. He could see

nothing of

his father, but felt that he could not leave him. As the mysterious

rays rising

from the bottom might have something to do with the accident, he made

up his

mind to follow them: they must, he thought, be reflections from the eye

of some

monster. It

was a deep dive, and for many minutes Matakichi was under water. At

last he

reached the bottom, and here he found an enormous colony of the awabi

(ear-shells). The space covered by them was fully 200 square feet, and

in the

middle of all was one of gigantic size, the like of which he had never

heard

of. From the holes at the top through which the feelers pass shot the

bright

rays which illuminated the sea, — rays which are said by the Japanese

divers to

show the presence of a pearl. The pearl in this shell, thought

Matakichi, must

be one of enormous size — as large as a baby's head. From all the awabi

shells

on the patch he could see that lights were coming, which denoted that

they

contained pearls; but wherever he looked Matakichi could see nothing of

his

father. He thought his father must have been drowned, and if so, that

the best

thing for him to do would be to regain the surface and repair to the

village to

report his father's death, and also his wonderful discovery, which

would be of

such value to the people of Nanao. Having after much difficulty reached

the

surface, he, to his dismay, found the boat broken by the sea, which was

now

high. Matakichi was lucky, however. He saw a bit of floating wreckage,

which he

seized; and as sea, wind, and current helped him, strong swimmer as he

was, it

was not more than half an hour before he was ashore, relating to the

villagers

the adventures of the day, his discoveries, and the loss of his dear

father. The

fishermen could hardly credit the news that what they had taken to be

supernatural lights were caused by ear-shells, for the much-valued

ear-shell

was extremely rare about their district; but Matakichi was a youth of

such

trustworthiness that even the most sceptical believed him in the end,

and had

it not been for the loss of Kansuke there would have been great

rejoicing in

the village that evening. Having

told the villagers the news, Matakichi repaired to the old priest's

house at

the end of the village, and told him also. 'And

now that my beloved father is dead,' said he, 'I myself beg that you

will make

me one of your disciples, so that I may pray daily for my father's

spirit.' The

old priest followed Matakichi's wish and said, 'Not only shall I be

glad to

have so brave and filial a youth as yourself as a disciple, but also I

myself

will pray with you for your father's spirit, and on the twenty-first

day from

his death we will take boats and pray over the spot at which he was

drowned.' Accordingly,

on the morning of the twenty-first day after the drowning of poor

Kansuke, his

son and the priest were anchored over the place where he had been lost,

and

prayers for the spirit of the dead were said. That

same night the priest awoke at midnight; he felt ill at ease, and

thought much

of the spiritual affairs of his flock. Suddenly

he saw an old man standing near the head of his couch, who, bowing

courteously,

said: 'I am

the spirit of the great ear-shell lying on the bottom of the sea near

Rocky

Island. My age is over woo years. Some days ago a fisherman fell from

his boat

into the sea, and I killed and ate him. This morning I heard your

reverence

praying over the place where I lay, with the son of the man I ate. Your

sacred

prayers have taught me shame, and I sorrow for the thing I have done.

By way of

atonement I have ordered my followers to scatter themselves, while I

have

determined to kill myself, so that the pearls that are in my shell may

be given

to Matakichi, the son of the man I ate. All I ask is that you should

pray for

my spirit's welfare. Farewell!' Saying

which, the ghost of the ear-shell vanished. Early next morning, when

Matakichi

opened his shutters to dust the front of his door, he found thereat

what he

took at first to be a large rock covered with seaweed, and even with

pink

coral. On closer examination Matakichi found it to be the immense

ear-shell

which he had seen at the bottom of the sea off Rocky Island. He rushed

off to

the temple to tell the priest, who told Matakichi of his visitation

during the

night. The

shell and the body contained therein were carried to the temple with

every

respect and much ceremony. Prayers were said over it, and, though the

shell and

the immense pearl were kept in the temple, the body was buried in a

tomb next

to Kansuke's, with a monument erected over it, and another over

Kansuke's

grave. Matakichi changed his name to that of Nichige, and lived

happily. There

have been no ear-shells seen near Nanao since, but on the rocky island

is

erected a shrine to the spirit of the ear-shell. NOTE. — A 3000-yen pearl which I know of was sold for 12 cents by a fisherman from the west. It came from a temple, belongs now to Mikomoto, and is this size.  |